Kerala History

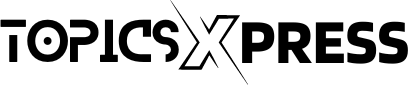

Kerala, located on the Malabar Coast of India, is a state renowned for its rich cultural heritage, natural beauty, and historical significance. It was officially established on November 1, 1956, through the States Reorganisation Act, combining Malayalam-speaking regions from Cochin, Malabar, South Canara, and Travancore. With a total area of 38,863 square kilometers, Kerala ranks as the 21st largest state in India. It shares borders with Karnataka to the north, Tamil Nadu to the east and south, and is flanked by the Lakshadweep Sea to the west. The state comprises 14 districts, with Thiruvananthapuram serving as its capital. Malayalam is the official and most widely spoken language.

Kerala boasts a remarkable history, being home to ancient dynasties like the Chera Kingdom, which dominated the region in the early Common Era. Other notable kingdoms included the Ay Kingdom in the south and the Ezhimala Kingdom in the north. The state was a significant player in the spice trade as early as 3000 BCE, earning mentions in ancient texts like Pliny’s works and the Periplus.

The Portuguese arrival in the 15th century marked the beginning of European colonial interests in the region, setting the stage for later colonization. During India’s independence movement, Kerala was divided among Travancore and Cochin princely states and the Malabar region of Madras Province. The modern state of Kerala was formed in 1956 by merging these regions.

Kerala has achieved extraordinary milestones in human development. It has India’s highest literacy rate at 96.2%, according to the 2018 National Statistical Office survey, and also leads in Human Development Index (HDI), with a score of 0.784 (2018). The state boasts the highest life expectancy at 77.3 years and an impressive sex ratio of 1,084 women per 1,000 men. Its low population growth rate (3.44%) and sustainable development efforts make it one of India’s most progressive states. Kerala also has the highest media exposure, with newspapers published in nine languages, primarily Malayalam and English.

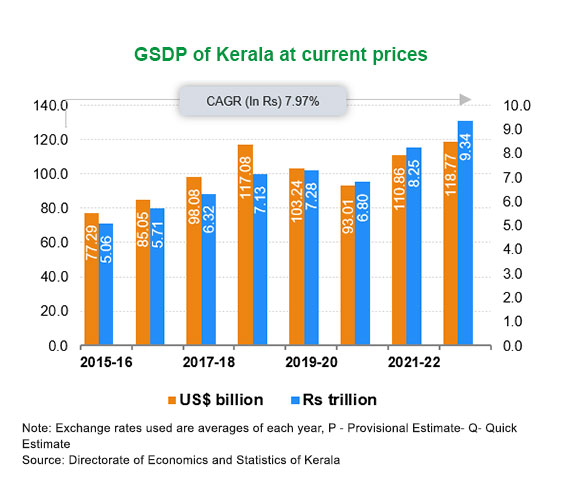

Economically, Kerala ranks as the eighth-largest state economy in India, with a Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) of ₹8.55 trillion (US$100 billion) in 2019–20 and a per capita net state domestic product of ₹222,000 (US$2,700). The tertiary sector contributes 65% of the state’s income, reflecting its reliance on services, while the primary sector contributes just 8%. A significant part of Kerala’s economy depends on remittances from its large expatriate community, particularly those in the Gulf nations. Kerala is also a leading producer of pepper, natural rubber, coconut, tea, coffee, cashew, and spices, which are integral to its agricultural economy. The state’s fishery industry, supported by its 595-kilometer coastline, contributes 3% to its income and sustains over 1.1 million people.

Kerala’s natural beauty and cultural richness make it a prominent tourist destination. Named one of the “ten paradises of the world” by National Geographic Traveler, the state is famous for its coconut-lined beaches, serene backwaters, lush hill stations, Ayurvedic wellness centers, and tropical greenery. Its biodiversity is complemented by the towering Western Ghats on its eastern boundary.

The origin of Kerala’s name is steeped in history and etymology. The earliest recorded mention is as Keralaputo (son of Chera) in a 3rd-century BCE rock inscription by Emperor Ashoka. The word “Kerala” is believed to be derived from the Old Tamil term ‘Cheral,’ referring to the Chera dynasty. A popular local interpretation links “Kerala” to the Malayalam words “kera” (coconut tree) and “alam” (land), aptly naming it the “land of coconuts.” Ancient texts such as the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Skanda Purana, and the Aitareya Aranyaka also reference Kerala, showcasing its long-standing cultural and historical importance.

Kerala was historically referred to as Malabar in international trade circles. The term “Malabar” was not limited to the present-day Kerala but also included regions like Tulu Nadu and Kanyakumari, which are adjacent to Kerala along India’s southwestern coast. The inhabitants of Malabar were known as Malabars. Before the arrival of the East India Company, “Malabar” and “Kerala” were often used interchangeably to refer to the region.

References to Kerala as Male date back to the 6th century CE, as noted by Cosmas Indicopleustes, a Byzantine traveler. In his work, he described a pepper emporium called Male, which later lent its name to “Malabar,” meaning the “country of Male.” The root of the name “Male” is believed to derive from the Dravidian word “Mala,” meaning hill.

The earliest recorded use of the term “Malabar” is attributed to Al-Biruni (973–1048 CE). Arab writers, including Ibn Khordadbeh and Al-Baladhuri, also mentioned the ports of Malabar in their texts. The region was referred to in various forms, such as Malibar, Manibar, Mulibar, and Munibar, by Arab traders. These names reflect the historical significance of the region as a hub for spice trade and maritime activity.

Some scholars, like William Logan, have traced the origin of “Malabar” to a combination of the Dravidian word “Mala” (hill) and the Persian or Arabic word “Barr” (country/continent), making it the “land of hills.” Another related term, Malanad, also means the “land of hills,” further emphasizing the geographical and cultural identity of this historic region.

History of Kerala

Kerala is a land of rich cultural heritage, ancient trade links, and captivating legends. From the mythical creation of its land to its prominence as a global spice hub, Kerala’s history is a remarkable journey shaped by diverse influences.

Mythological Origins

Kerala’s history begins with mythological tales deeply rooted in Hindu traditions. The state is believed to have been reclaimed from the sea by Parashurama, the sixth avatar of Vishnu. Legend states that Parashurama threw his axe into the sea, causing the waters to recede and create a fertile strip of land stretching from Gokarna to Kanyakumari. This reclaimed land, known as Parashurama Kshetram, became Kerala. However, the soil was initially barren and unsuitable for life. To resolve this, the Snake King Vasuki blessed the land with holy poison, enriching its fertility and greenery.

Another significant legend is about Mahabali, a just and benevolent king associated with the festival of Onam. Mahabali was an Asura king who ruled Kerala with fairness, creating a golden era of prosperity. However, Vishnu, in his Vamana avatar, banished Mahabali to the netherworld to restore the balance of power. It is believed that Mahabali returns once a year during Onam to visit his subjects.

These mythological narratives highlight Kerala’s cultural connection to its divine origins. They are celebrated through rituals and festivals, making Kerala a land of legends and spirituality.

Pre-History and Early Settlements

Kerala’s historical roots stretch back to prehistoric times, with evidence of human habitation found in the region’s archaeological sites. It is hypothesized that much of Kerala’s coastal plains were once submerged under the sea. Marine fossils discovered near Changanassery substantiate this theory.

The Neolithic dolmens in Marayur, locally called Muniyaras, indicate the presence of early settlers. These dolmens, built with stone slabs, served as burial chambers for the region’s ancient inhabitants. The rock engravings in Edakkal Caves in Wayanad are another fascinating relic from around 6000 BCE. These carvings depict human figures, symbols, and animals, providing glimpses into the lives of Kerala’s earliest inhabitants.

Kerala’s development through the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic ages showcases its continuous habitation and evolving culture. Studies also suggest that Kerala’s culture may have connections to the Indus Valley Civilization, particularly during the late Bronze and early Iron Ages.

The archaeological richness of Kerala, from dolmens to cave engravings, highlights its importance in understanding the prehistoric history of India.

Ancient Trade and Global Connections

Kerala has been an integral part of the global trade network since ancient times, primarily due to its abundant spices. Known as the “Spice Garden of India”, the state’s pepper, cinnamon, and cardamom have attracted traders for millennia. Historical records suggest that Kerala’s spice trade dates back to 3000 BCE, with ancient civilizations such as the Babylonians, Assyrians, and Egyptians establishing trade links.

The port of Muziris (modern Kodungallur) was a major trading hub during the Sangam period. It served as a gateway for Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and Phoenicians to access Kerala’s prized spices. Tyndis, another ancient port, also played a significant role in connecting the Chera kingdom with the Roman Empire.

Kerala’s interaction with West Asian and Mediterranean civilizations shaped its culture and economy. For instance, Jewish traders settled in Kerala as early as 573 BCE, establishing a thriving community. Similarly, Christianity is believed to have arrived in Kerala in the 1st century CE through Saint Thomas, one of Jesus Christ’s apostles.

These trade connections have left an indelible mark on Kerala’s cultural landscape, blending indigenous traditions with global influences. The state’s prominence in ancient trade showcases its significance in the history of global commerce.

Chera Dynasty and Sangam Age

The Chera dynasty was a prominent power that ruled Kerala during the Sangam age (circa 3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE). The Cheras established their capital in Kuttanad and controlled significant trade routes and ports, including Muziris. The dynasty’s trade relations with the Roman Empire brought prosperity and cultural exchange to Kerala.

The Cheras were not the only rulers of the region. The northern areas were dominated by the Mushika dynasty, while the southern regions were governed by the Ays. These smaller kingdoms coexisted and contributed to Kerala’s vibrant political landscape.

The Sangam literature provides valuable insights into this period, describing the Cheras as powerful rulers who promoted trade and culture. The ports of Muziris and Tyndis became hubs for spices, silk, and ivory, connecting Kerala to international markets.

The Sangam age is also significant for its literary achievements. Poets of this era praised the fertility of Kerala’s land, its lush greenery, and the valor of its kings. The Cheras’ emphasis on trade and culture made Kerala an influential region in ancient India.

Cultural Syncretism and Legacy

Kerala’s history is marked by its cultural openness and ability to assimilate diverse influences. Its interactions with Arab, Jewish, Christian, and Roman traders brought new ideas, religions, and technologies. These influences were seamlessly integrated into Kerala’s own traditions, creating a unique cultural identity.

The Cheraman Perumal legends, associated with the division of Kerala’s lands, are a testament to the state’s enduring oral traditions. The story of the Zamorins of Kozhikode, who rose to prominence after receiving the Cheraman Perumal’s sword, illustrates Kerala’s historical shifts in power.

Kerala’s legacy as a land of culture and trade continues to this day. Its historical connections to ancient civilizations and mythological significance make it a fascinating study of resilience and adaptation.

Early Medieval Period: Formation and Cultural Evolution in Kerala

The Second Chera Kingdom

During the early medieval period, the establishment of the second Chera Kingdom, also known as the Kulasekhara dynasty of Mahodayapuram (c. 800–1102 CE), played a pivotal role in Kerala’s history. Founded by Kulasekhara Varman, this kingdom unified modern-day Kerala and parts of Tamil Nadu. The southern regions, initially under the Ay kings, were incorporated into the Kulasekhara Empire by the 10th century, marking a significant shift in power dynamics.

This period heralded an era of cultural, literary, and artistic development. The Bhakti movement gained momentum, shaping Kerala’s religious and social fabric. A distinct Keralite identity emerged during the seventh century, as Malayalam evolved as a separate language from Tamil. The introduction of the Malayalam calendar in 825 CE further solidified this identity.

Trade and Local Governance

Kerala’s strategic location enabled flourishing trade networks with the Middle East and China. The Quilon Syrian copper plates, granted by the Venad ruler Sthanu Ravi Varma, highlight the extensive trade and merchant guilds operating during this time. Provinces under Naduvazhis and Desams under Desavazhis ensured effective local administration. The Mamankam festival, celebrated at Tirunavaya, became a symbol of Kerala’s cultural vibrancy.

Key Highlights:

- Establishment of the second Chera Kingdom under Kulasekhara Varman.

- Evolution of Malayalam as a distinct language.

- The Quilon Syrian copper plates: a testimony to international trade.

- Emergence of the Bhakti movement, fostering religious harmony.

The Rise of Kozhikode and the Zamorin Kingdom

Emergence of Principalities

The decline of the Chera Kingdom around 1102 CE led to the fragmentation of Kerala into multiple warring principalities. Among these, Kozhikode (Calicut) rose to prominence under the Zamorin rulers, emerging as the most powerful kingdom in the region. The Zamorin, initially a minor ruler of Eranad, transformed Kozhikode into a thriving hub of trade and commerce through strategic alliances with Arab and Chinese merchants.

Kozhikode as a Trade Epicenter

Kozhikode became an important trade port, overshadowing Kollam, Kochi, and Kannur. Travelers like Ibn Battuta and Ma Huan described Kozhikode as a bustling emporium frequented by merchants from around the world. The construction of fortifications, like the one at Ponnani, strengthened the Zamorin’s military and economic power.

Impact of Vijayanagara Conquests

During the 15th century, Deva Raya II of the Vijayanagara Empire briefly subdued Kerala, defeating the Zamorin and other rulers. Despite this, Kozhikode regained prominence as Vijayanagara influence waned.

Key Highlights:

- Kozhikode’s rise as the most influential kingdom in medieval Kerala.

- Strategic alliances with Arab and Chinese traders.

- Accounts of Kozhikode’s prosperity by travelers like Ibn Battuta and Ma Huan.

- Temporary Vijayanagara conquest under Deva Raya II.

Early Modern Period: European Incursions and the Portuguese Era

The Arrival of Vasco da Gama

The discovery of a sea route to Kozhikode by Vasco da Gama in 1498 marked a turning point in Kerala’s history. It initiated the European Age of Discovery, bringing Portuguese dominance to the Malabar Coast. The Portuguese established trading posts in Tangasseri (Quilon) and Kochi, disrupting Arab maritime trade in the Arabian Sea.

Resistance and Naval Defense

The Zamorins, allied with the Arab merchants, resisted Portuguese incursions. Notable figures like the Kunjali Marakkars organized the first naval defense in India, challenging Portuguese supremacy. Despite initial setbacks, the Portuguese faced defeat at Chaliyam Fort in 1571 at the hands of Zamorin forces.

Cultural Developments

This period saw the rise of Malayalam literature, with Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan, the father of modern Malayalam, making significant contributions. The social system became more stratified, influenced by the decline of Buddhism and Jainism and the strengthening of caste-based divisions.

Key Highlights:

- Vasco da Gama’s arrival and the Portuguese establishment on the Malabar Coast.

- Naval resistance by the Kunjali Marakkars against European forces.

- Growth of Malayalam literature during Portuguese rule.

The Rise of Travancore and British Influences

Travancore’s Consolidation

The 18th century saw the rise of Travancore under Marthanda Varma, who unified smaller kingdoms and defeated European powers like the Dutch at the Battle of Colachel in 1741. The “Treaty of Mavelikkara” curtailed Dutch influence, marking the dominance of the Travancore kingdom.

British Entry into Kerala

The British East India Company established its presence in Kerala by allying with local rulers like the Kochi kingdom. By the mid-18th century, the British directly controlled the Malabar region, Fort Kochi, and Tangasseri. The municipality of Fort Kochi, established in 1664 by the Dutch, became the first of its kind in India.

Cultural and Political Impacts

Kerala’s political landscape underwent significant changes under Travancore’s centralized rule. The kingdom became a hub of cultural and administrative advancements, with Thiruvananthapuram emerging as a key city.

Key Highlights:

- Travancore’s rise as the dominant power in Kerala.

- Defeat of Dutch forces and the establishment of British influence.

- Growth of Thiruvananthapuram as a major center.

This layered history of medieval and early modern Kerala highlights its evolution as a cultural, trade, and political powerhouse. From the Kulasekhara dynasty to European colonization, each phase shaped Kerala’s unique identity.

Geography and Climate of Kerala: A Natural Marvel

Geography of Kerala

Nestled between the Lakshadweep Sea to the west and the Western Ghats to the east, Kerala spans a unique geographical tapestry. With its location between latitudes 8°18′ N to 12°48′ N and longitudes 74°52′ E to 77°22′ E, the state enjoys a humid tropical rainforest climate. It boasts a 590 km-long coastline and a terrain that transitions from low-lying coastal plains to rolling midlands and rugged highlands.

- Mountainous Highlands: The Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, dominate Kerala’s eastern region with peaks like Anamudi (2,695 m), the highest in South India. These hills are a biodiversity hotspot and older than the Himalayas, home to lush forests, deep valleys, and stunning waterfalls such as the Athirappilly Falls, often called the “Niagara of India.”

- Coastal Plains and Backwaters: Kerala’s coastline is crisscrossed with interconnected canals, lakes, and rivers, forming the Kerala Backwaters, including Vembanad Lake, the longest in India. The Kuttanad region, known as “The Rice Bowl of Kerala,” is among the few places globally where farming occurs below sea level.

Natural Resources

Kerala’s mineral wealth includes ilmenite, monazite, thorium, and titanium found along its coastal belt. Wayanad, known for its plateau, and the eastern districts of Nilambur, Malappuram, and Palakkad are part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, rich in natural gold fields.

The coastal regions are notable for their background radiation due to monazite-rich sands, with Karunagappally having some of the highest radiation levels globally.

Rivers and Waterways

Kerala has 44 rivers, most of which are west-flowing and monsoon-fed. Key rivers include:

- Periyar River (244 km): The longest river in the state.

- Bharathapuzha (209 km): Known for its cultural significance.

- Pamba River (176 km): Sacred in Hindu traditions.

While Kerala’s waterways cover about 8% of India’s navigable routes, environmental challenges like sand mining and pollution threaten their sustainability.

Climate of Kerala

Kerala’s climate is influenced by the Southwest Monsoon (June to August) and the Northeast Monsoon (September to December). With an average annual rainfall of 2,923 mm, the state experiences one of the wettest climates in India.

- Rainfall Patterns: The Southwest Monsoon delivers 65% of Kerala’s rainfall, marking the state as the first to receive monsoon showers in India. The eastern highlands receive the highest precipitation, over 5,000 mm annually.

- Temperature Range: Kerala’s daily temperatures range from 19.8°C to 36.7°C, with coastal areas averaging 25°C to 27.5°C and the highlands remaining cooler at 20°C to 22.5°C.

Natural Hazards

Kerala is vulnerable to natural calamities like:

- Floods: The 2018 floods were among the worst in a century, while the 2024 landslides marked a grim milestone in the state’s history.

- Cyclones and Droughts: The summer season brings cyclones and storm surges, exacerbating coastal erosion.

Unique Features

Kerala’s biodiversity, enriched by its climate and topography, is globally recognized. From the rolling tea gardens of Wayanad to the pristine beaches of Vakala, the state’s geography shapes its identity as “God’s Own Country.” The state’s environmental richness, coupled with its strategic location, underscores its importance in India’s ecological and cultural landscape.

Kerala’s Flora and Fauna

Diverse Ecosystems and Rich Biodiversity

Kerala boasts a remarkable variety of flora and fauna, thanks to its unique topography and climatic conditions. The state is home to an extensive range of ecosystems, including tropical rainforests, coastal wetlands, and montane forests. Much of Kerala’s biodiversity is concentrated in the Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the world’s “hottest hotspots” for biological diversity.

Flora of Kerala

Kerala’s lush vegetation includes over 4,000 species of flowering plants, of which 1,272 are endemic, and nearly 900 are used in traditional medicine. Forests cover 24% of the state and are classified as:

- Tropical Wet Evergreen and Semi-Evergreen Forests: Found at lower and middle elevations, covering 3,470 km².

- Tropical Moist and Dry Deciduous Forests: Spread across mid-elevation areas.

- Shola Forests: Found in the highest elevations, characterized by montane subtropical and temperate vegetation.

Important plant species include bamboo, wild cardamom, wild black pepper, teak, and aromatic vetiver grass. Notable locations such as Cardamom Hills and Silent Valley National Park harbor unique species and demonstrate the state’s commitment to biodiversity conservation.

Fauna of Kerala

Kerala’s wildlife is equally diverse, with:

- 118 mammal species, including the Indian elephant, Bengal tiger, Nilgiri tahr, and Indian leopard.

- 500 bird species, such as the Malabar trogon, great hornbill, and Kerala laughingthrush.

- 173 reptile species (10 endemic), including the king cobra and mugger crocodile.

- 151 amphibian species, 36 of which are endemic.

The state’s wetlands and water bodies, such as the Vembanad Lake and Kadalundi Bird Sanctuary, attract migratory birds and are crucial for aquatic biodiversity.

Conservation Efforts

Kerala is a leader in wildlife conservation, with protected areas like:

- Silent Valley National Park: Preserving pristine tropical rainforest.

- Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve and Agasthyamala Biosphere Reserve: Covering significant biodiversity hotspots.

- Ramsar Wetlands: Including Lake Sasthamkotta and Ashtamudi Lake.

Despite its efforts, Kerala’s biodiversity faces threats from habitat destruction, deforestation, and climate change, necessitating ongoing and enhanced conservation measures.

Administrative Divisions, Districts, and Urban Centers

Administrative Structure

Kerala’s governance structure is divided into 14 districts, grouped into six regions:

- North Malabar

- South Malabar

- Kochi

- Northern Travancore

- Central Travancore

- Southern Travancore

Each district is subdivided into 27 revenue divisions, 75 taluks, and 1,674 revenue villages, forming a well-organized administrative framework.

Local Self-Government

Following India’s 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments, Kerala adopted a three-tier governance model:

- District Panchayats: 14

- Block Panchayats: 152

- Grama Panchayats: 941

- Municipal Corporations: 6

- Municipalities: 87

The Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation, established in 1940, is Kerala’s oldest, while the Kochi Urban Agglomeration is the largest metropolitan area.

Major Urban Centers

- Thiruvananthapuram: Kerala’s capital, known for its cultural and administrative significance.

- Kochi: The economic hub and a gateway to Kerala’s backwaters.

- Kozhikode: A historic city with a legacy of trade and culture.

- Kollam, Thrissur, and Kannur: Other major cities known for their unique contributions to Kerala’s heritage and economy.

In 2007, these cities ranked among India’s best places to live, reflecting their strong performance in health, education, and public facilities.

Historical Significance of Urban Governance

Kerala’s urban history is notable for innovations like the Fort Kochi Municipality (established in 1664 by Dutch Malabar), one of India’s earliest municipalities. Post-independence, Kerala continued to lead in urban planning and governance.

Government and Administration in Kerala

Kerala operates under a parliamentary system of representative democracy, with a unicameral legislature known as the Kerala Legislative Assembly (Niyamasabha). The assembly consists of 140 elected members, who serve a term of five years. The state sends 20 representatives to the Lok Sabha (lower house of the Indian Parliament) and 9 members to the Rajya Sabha (upper house).

The Governor of Kerala, appointed by the President of India, serves as the ceremonial head of the state. The Chief Minister, who is the leader of the majority party or coalition in the assembly, is responsible for running the state. The Council of Ministers, appointed on the Chief Minister’s advice, handles executive functions. Departments are managed by Principal Secretaries or Additional Chief Secretaries, who are senior Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officers.

Kerala’s judiciary system is headed by the Kerala High Court, located in Kochi. The court has a Chief Justice and multiple permanent and additional judges. It also oversees the Union Territory of Lakshadweep. Below the High Court, a robust network of lower courts ensures justice delivery across districts.

Local governance in Kerala is notable for its decentralization. The state implemented a three-tier Panchayati Raj system in 1994, consisting of Gram Panchayats, Block Panchayats, and District Panchayats. For urban areas, Municipalities and Corporations govern local matters. These bodies are allocated significant administrative and financial powers, with around 40% of the state’s plan funds directed toward local governments.

Kerala is known for its progressive governance. It was declared India’s first digital state in 2016 and ranked as the least corrupt state in the country by the India Corruption Survey 2019. The Public Affairs Index 2020 recognized Kerala as the best-governed state in India, reflecting its effective governance and administrative capabilities.

Industries in Kerala

Kerala is home to a range of traditional industries that have shaped its economic landscape over the years. Among the most significant are the coir, handloom, and handicraft sectors, which together provide employment to around one million people. Kerala supplies about 60% of the total global production of white coir fiber, making it a dominant player in this field. The state’s coir industry began with India’s first coir factory established in Alleppey in 1859–60, and further development was supported by the Central Coir Research Institute founded in 1959.

Additionally, the state has a thriving micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSME) sector, with approximately 1.47 million MSMEs employing over 3 million people. The Kerala State Industrial Development Corporation (KSIDC) has also played a significant role in the promotion of over 650 medium and large-scale manufacturing firms across the state, directly creating employment for 72,500 individuals.

Although Kerala’s economy is primarily based on agriculture, the mining sector also contributes modestly to the state’s Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP). Extracted minerals include ilmenite, kaolin, bauxite, silica, quartz, rutile, zircon, and sillimanite. Alongside these traditional industries, Kerala’s economy benefits from other prominent sectors such as tourism, medical services, education, banking, shipbuilding, and business process outsourcing (BPO).

Agriculture in Kerala

Agriculture has always been an integral part of Kerala’s identity, with crops such as black pepper, rubber, coconut, and spices forming the backbone of the state’s agricultural output. Kerala produces 97% of India’s black pepper and accounts for around 85% of the nation’s natural rubber. The state’s land is also well-known for cultivating a variety of other crops, including cashews, tea, coffee, and cardamom—the latter being a significant cash crop with Kerala producing 90% of India’s cardamom. The state is also the second-largest producer of cardamom globally.

Historically, Kerala was a major producer of rice, but by the 1970s, rice cultivation decreased due to rising labor costs, shifts in land use, and increased availability of rice from other regions. Consequently, much of the agricultural land was repurposed for perennial crops like coconut and rubber. Despite these shifts, Kerala continues to lead in coconut cultivation, covering more land than any other state in India.

A key feature of Kerala’s agricultural sector is the prominence of home gardens, which contribute significantly to local food security and the economy. Additionally, fisheries are another important sector that sustains thousands of families and significantly contributes to the state’s economy.

Fisheries Industry

Kerala is one of the leading producers of fish in India, benefiting from its 590 kilometers of coastline and 400,000 hectares of inland water resources. The state has an active workforce of approximately 220,000 fishermen, and around 11 lakh (1.1 million) people are engaged in various fishing and allied activities, such as drying, processing, packaging, and exporting fish. Kerala contributes to around 22% of India’s marine fishery yield, with 6.08 lakh tons of fish harvested annually.

The fisheries sector is heavily influenced by natural phenomena such as chakara, a seasonal event that leads to a calm ocean along Kerala’s coast, which boosts fish output. This rich ecosystem provides a wide variety of fish, including pelagic species, demersal species, crustaceans, and mollusks. The fishing villages along the coast, as well as in the inland waters, play an essential role in Kerala’s economy. With the growing demand for seafood exports, Kerala has solidified its position as a major player in the fishing industry.

Transportation in Kerala

Kerala boasts an extensive and well-connected road network that spans over 331,904 kilometers. This accounts for 5.6% of India’s total road infrastructure. The state’s road network includes a mix of national highways, state highways, district roads, and rural roads. National Highway 66, which runs from Kanyakumari to Mumbai, traverses through several key cities in Kerala, including Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram, and Kollam, making it a crucial artery for transportation and trade.

Despite this vast network, Kerala faces challenges in traffic density, which is nearly four times the national average. The state’s roads are also among the narrowest in the country, contributing to high accident rates. Road safety continues to be a concern, with narrow roads and reckless driving being major causes of accidents. The Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC), founded in 1937, is an essential component of public transportation in the state, with over 5,373 buses serving 4795 routes.

In addition to roadways, Kerala has extensive infrastructure projects underway, such as the development of hill and coastal highways under the Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIIFB). Public transportation projects like the Vyttila Mobility Hub and the Kerala Urban Road Transport Corporation (KURTC) are also part of the state’s push to improve its transportation systems and reduce congestion.

Kerala’s Economy

Kerala has a diverse and evolving economy, transitioning from an agrarian base to a service-driven model. As of 2019-20, the service sector contributed 63% to the state’s Gross State Value Added (GSVA), followed by the secondary sector (28%) and the primary sector (8%).

Key Industries in Kerala:

- Primary Sector: Kerala is a major producer of cash crops like coconut, rubber, tea, coffee, pepper, and cardamom, contributing significantly to India’s output. However, the cultivation of food crops has been declining since the 1950s.

- Secondary Sector: Industrial activities include shipbuilding, oil refining, food processing, and rubber-based industries. The Cochin Shipyard is one of India’s prominent shipbuilding hubs.

- Tertiary Sector: Tourism, Ayurveda, education, IT, healthcare, and financial services dominate. Technopark in Thiruvananthapuram is India’s largest IT park and a symbol of Kerala’s technological advancement.

NRI Contributions:

Kerala’s economy relies heavily on remittances from Non-Resident Indians (NRIs). The state experienced a Gulf Boom in the 1970s, leading to significant migration. In 2020, NRI deposits exceeded ₹1 lakh crore, showcasing their vital role in the economy.

Despite its achievements, Kerala faces challenges such as unemployment (especially among educated women), environmental fragility, and budget deficits. However, initiatives like the Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIIFB) aim to address these issues by mobilizing funds for large-scale projects.

Railways:

- Southern Railway Zone operates the state’s rail network.

- Key Railway Stations: Thiruvananthapuram Central (busiest), Ernakulam Junction, Kozhikode, Kollam Junction, Thrissur, Palakkad Junction.

- Historic Railway Milestones: First railway line from Tirur to Chaliyam (1861), Shoranur Junction (1862) is the largest railway junction in Kerala, crucial for connecting the southwestern and southeastern coasts.

Kochi Metro:

- Kochi Metro: Only metro system in Kerala, operational since 2012.

- Notable Features: First Indian metro to use a Communication-Based Train Control (CBTC) system.

- Recognition: Named “Best Urban Mobility Project” in 2017.

Airports:

- Four International Airports: Thiruvananthapuram, Cochin, Calicut, Kannur.

- Cochin International Airport: Busiest, world’s first fully solar-powered airport, and the first Indian airport to be publicly listed.

- Historical Significance: Thiruvananthapuram and Calicut are among South India’s oldest airports.

Water Transport:

- Major Ports: Kochi and Vizhinjam.

- West-Coast Canal: Kerala’s longest waterway (616 km), connecting Kasaragod to Poovar.

- Challenges: Silting, water hyacinth growth, and lack of maintenance hinder inland navigation.

Kochi Water Metro:

- Kochi Water Metro: India’s first integrated water transport system, covering 76 kilometers with 78 electric hybrid boats.

- Complementary to Kochi Metro: Connects Island communities with the mainland, serving as a feeder service for areas with limited road access.

Key Demographic Highlights of Kerala:

- Population Growth: Kerala’s population grew from 6.4 million in 1901 to 33.4 million in 2011. The state has the lowest population growth rate in India, with a decadal growth of just 4.9% between 2001 and 2011.

- Population Density: Kerala has a population density of 859 persons per km², which is nearly three times the national average. The coastal regions are the most densely populated, while the eastern hills and mountains are sparsely populated.

- Urbanization: Kerala is the second-most urbanized major state in India, with 47.7% of its population living in urban areas (as per the 2011 Census).

- Indigenous Population: The state is home to approximately 321,000 indigenous tribal Adivasis, accounting for 1.1% of the population, primarily living in the eastern regions.

- Sex Ratio: Kerala has a unique sex ratio of 1.084 females to every male, making it the only state in India where women outnumber men. This is attributed to historical and cultural factors, including matrilineal inheritance traditions.

Key Points on Gender and LGBT Rights:

- Women’s Empowerment: Kerala has a strong tradition of female empowerment, supported by high female literacy rates, work participation, and life expectancy. Women in Kerala have a higher social standing due to both historical matrilineal inheritance systems and Christian missionary influence on female education.

- LGBT Rights: Kerala has been at the forefront of LGBT rights in India. It was one of the first states to introduce welfare policies for the transgender community and has enacted progressive laws like free sex reassignment surgery and legal recognition for transgender individuals. Kerala hosts the annual Kerala Queer Pride Parade, advocating for LGBT rights.

Human Development:

- Human Development Index (HDI): Kerala ranks first in India in terms of Human Development Index (HDI), reflecting its high achievements in health, education, and standard of living. The state’s HDI was 0.770 in 2015, classifying it as a high human development state.

- Literacy and Life Expectancy: Kerala boasts the highest literacy rate in India at 94% (as per the 2011 census), and life expectancy is among the highest in the country, with an average of 74 years in 2011.

- Poverty and Inequality: Kerala has made significant progress in reducing poverty. The poverty rate in rural Kerala fell from 59% in 1973–1974 to just 12% by 1999–2010.

- Health Care: Kerala is a leader in public health initiatives and is known for its universal healthcare program. The state also has the lowest infant mortality rate in India and was the first to achieve 100% institutional deliveries. It is recognized for its palliative care services and a focus on traditional medicine like Ayurveda.

Key Statistics on Major Cities (2011 Census):

- Thiruvananthapuram: The most populous city in Kerala with 968,990 residents.

- Kozhikode: Second-most populous, with 609,224 people.

- Kochi: Third-most populous, with 602,046 residents.

- Other Major Cities: Kollam (388,288), Thrissur (315,957), Kannur (232,486).

Migration and Demographic Trends:

- Migration Impact: Kerala has a significant expatriate population, with a large number of people migrating for work, particularly to the Gulf countries. This has led to social and economic transformations within Kerala, such as remittance-driven development.

- Aging Population: Kerala is undergoing a “demographic transition,” with an increasing proportion of elderly people, posing challenges and opportunities in terms of healthcare and social services.

1. Languages of Kerala

Malayalam is the official language of Kerala, spoken by 97.02% of the population. It holds the prestigious status of being one of the six Classical Languages of India. Aside from Malayalam, Tamil is also widely spoken, especially in the Idukki and Palakkad districts, where it accounts for 17.48% and 4.8%, respectively. The northern region of Kasaragod is home to significant populations speaking Tulu (8.77%) and Kannada (4.23%), both integral to the region’s cultural identity.

2. Religion in Kerala

Kerala is one of India’s most religiously diverse states, with three major religions—Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity—coexisting harmoniously. According to the 2011 Census, 54.7% of the population follows Hinduism, 26.6% Islam, and 18.4% Christianity. Kerala has the largest Christian population in India, with multiple Christian denominations, including Syro-Malabar, Jacobite Syrian, and Latin Catholic. Islam arrived early, with the arrival of traders in the 7th century, and significant Muslim communities are found, especially in districts like Malappuram.

3. History and Cultural Heritage

The history of Kerala is rich and intertwined with influences from various dynasties and cultures. The Chera dynasty played a key role in shaping Kerala’s history, with its capital at Vanchi (modern-day Kodungallur). It was also the site of the arrival of the first mosque in India, established by the Cheraman Perumal. Over time, Kerala witnessed the establishment of European colonies by the Portuguese, Dutch, and British, each leaving behind their cultural imprints. The state’s cultural landscape is marked by classical art forms like Kathakali, Mohiniyattam, and Theyyam, which are celebrated globally.

4. Education in Kerala

Education has always been a focal point in Kerala’s development. Kerala boasts a 93.9% literacy rate, making it one of the most educated states in India. The state was the first to achieve 100% primary education and ranks top in the Education Development Index (EDI). The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics made significant contributions in the 14th-16th centuries. Modern education in Kerala began in the 19th century, with social reformers advocating for inclusive education. Today, the state is home to prestigious institutions like the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Kozhikode and the University of Kerala.

5. Tourism in Kerala

Kerala, often called “God’s Own Country,” is a renowned tourist destination known for its beaches, backwaters, hill stations, and wildlife. The state is famous for its pristine beaches such as Kovalam and Varkala, while the backwaters of Alappuzha and Kumar Akom attract visitors for houseboat cruises. The hill stations of Munnar and Wayanad offer scenic beauty, tea plantations, and trekking trails. Kerala is also home to many wildlife sanctuaries, including Periyar and Silent Valley. The state’s Ayurvedic wellness centers further add to its appeal, offering traditional healing practices to tourists.

6. Economy of Kerala

Kerala’s economy is driven by a combination of agriculture, remittances, tourism, and industry. The state is one of the top producers of rubber, coconut, tea, and spices in India. Kerala has developed a thriving service sector, with a major contribution from tourism and healthcare services. Overseas remittances, particularly from the Middle East, have significantly boosted the state’s economy, providing a steady source of income for many families. The industrial sector is focused on traditional industries like coir, handlooms, and cashew processing, alongside the emerging IT and biotech sectors.

7. Politics and Government

Kerala follows a parliamentary system of government and is known for its active political engagement and literacy-driven electorate. The state has witnessed the rise of strong political parties, such as the Left Democratic Front (LDF) and the United Democratic Front (UDF). Kerala was the first state in India to have a democratically elected Communist government, which has played a central role in shaping the state’s political landscape. The state has a history of social reforms that were supported by both left-leaning and right-leaning political forces, with a strong focus on improving education, healthcare, and social welfare.

Cuisine

Cuisine of Kerala

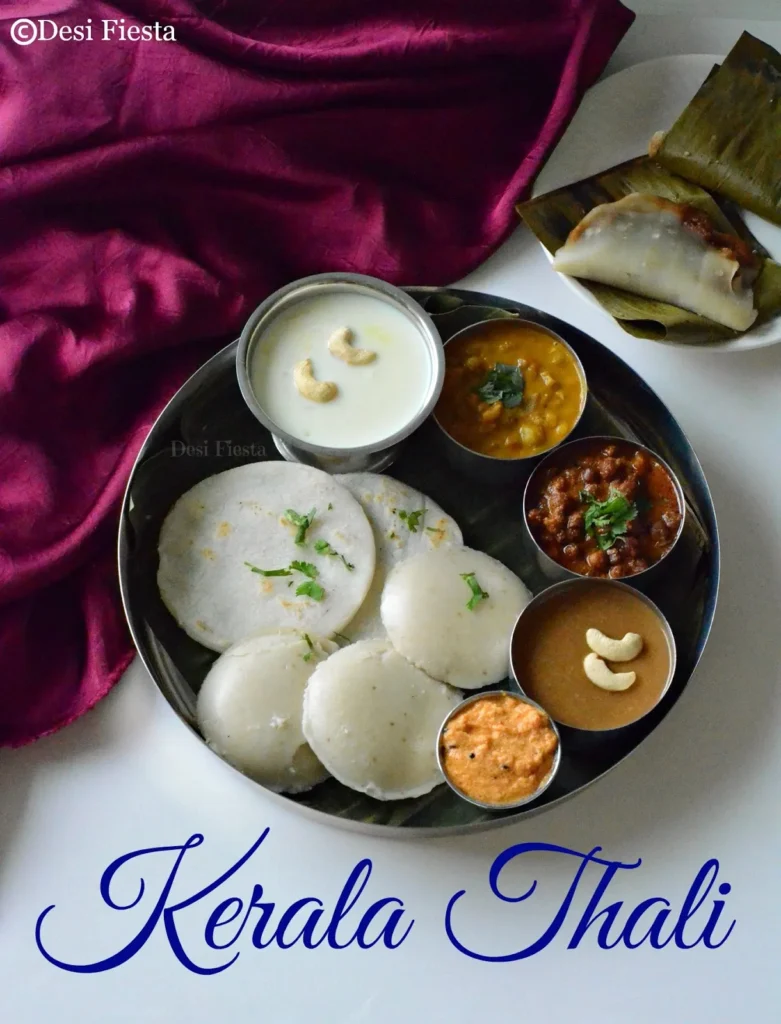

Kerala cuisine includes a wide variety of vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes prepared using fish, poultry, and meat. Culinary spices have been cultivated in Kerala for millennia and they are characteristic of its cuisine. Rice is a dominant staple that is eaten at all times of day. A majority of the breakfast foods in Kerala are made out of rice, in one form or the other (idli, dosa, puttu, pathiri, appam, or idiyappam), tapioca preparations, or pulse-based vada. These may be accompanied by chutney, kadala, payasam, payar pappadam, appam, chicken curry, beef fry, egg masala and fish curry. Porotta and Biryani are also often found in restaurants in Kerala.

Thalassery biryani is popular as an ethnic brand. Lunch dishes include rice and curry along with rasam, pulisherry, and sambar. Sadhya is a vegetarian meal, which is served on a banana leaf and followed with a cup of payasam. Popular snacks include banana chips, yam crisps, tapioca chips, Achappam, Unni appam and kuzhalappam. Seafood specialties include karimeen, prawns, shrimp and other crustacean dishes. Thalassery Cuisine is varied and is a blend of many influences.

Elephants

Elephants have been an integral part of the culture of the state. Almost all of the local festivals in Kerala include at least one richly caparisoned elephant. Kerala is home to the largest domesticated population of elephants in India—about 700 Indian elephants, owned by temples as well as individuals. These elephants are mainly employed for the processions and displays associated with festivals celebrated all around the state.

More than 10,000 festivals are celebrated in the state annually and some animal lovers have sometimes raised concerns regarding the overwork of domesticated elephants during them. In Malayalam literature, elephants are referred to as the “sons of the sahya”. The elephant is the state animal of Kerala and is featured on the emblem of the Government of Kerala.

Media

Media in Kerala

The media, telecommunications, broadcasting, and cable services are regulated by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI). The National Family Health Survey – 4, conducted in 2015–16, ranked Kerala as the state with the highest media exposure in India. Dozens of newspapers are published in Kerala, in nine major languages, but principally Malayalam and English. Kerala has the highest media exposure in India.

The most widely circulated Malayalam-language newspapers are Malayala Manorama, Mathrubhumi, Deshabhimani, Madhyamam, Kerala Kaumudi, Mangalam, Chandrika, Deepika, Janayugam, Janmabhumi, Siraj Daily and Suprabhaatham. Major Malayalam periodicals include Mathrubhumi Azhchappathippu, Vanitha, India Today Malayalam, Madhyamam Weekly, Grihalakshmi, Dhanam, Chithrabhumi and Bhashaposhini. The Hindu is the most read English language newspaper in the state, followed by The New Indian Express.

Sports

Main article: Sports in Kerala

The annual snake boat race is performed during Onam on the Pamba River. By the 21st century, almost all of the native sports and games from Kerala have either disappeared or become just an art form performed during local festivals, including Poorakkali, Padayani, Thalappandukali, Onathallu, Parichamuttukali, Velakali, and Kilithattukali. However, Kalaripayattu, regarded as “the mother of all martial arts in the world”, is practised as the indigenous martial sport. Another traditional sport of Kerala is the boat race, especially the race of Snake boats.

Cricket and football became popular in the state; both were introduced in Malabar during the British colonial period in the 19th century. Cricketers, like Tinu Yohannan, Abey Kuruvilla, Chundangapoyil Rizwan, Sreesanth, Sanju Samson and Basil Thampi found places in the national cricket team. Kerala has only performed well recently in the Ranji Trophy cricket competition, in 2017–18 reaching the quarterfinals for the first time in history.

Football is one of the most widely played and watched sports with huge in this state support for club and district level matches. Kochi hosts Kerala Blasters FC in the Indian Super League. The Blasters are one of the most widely supported clubs in the country as well as the fifth most followed football club from Asia in the social media. Kerala is one of the major footballing states in India along with West Bengal and Goa and has produced national players like I. M. Vijayan, C. V. Pappachan, V. P. Sathyan, U. Sharaf Ali, Jo Paul Ancheri, Ashique Kuruniyan, Muhammad Rafi, Jiju Jacob, Mashoor Shereef, Pappachen Pradeep, C.K. Vineeth, Anas Edathodika, Sahal Abdul Samad, and Rino Anto.

Tourism in Kerala

Kerala, often referred to as “God’s Own Country,” is one of the most popular and sought-after tourist destinations in India. Its unique blend of rich culture, diverse traditions, varied demographics, and breathtaking natural beauty makes it a dream destination for both domestic and international travelers.

Key Attractions Driving Kerala’s Tourism

- Beaches and Backwaters: Kerala is home to some of the most picturesque beaches in India, including Kovalam, Varkala, Cherai, and Bekal. These beaches are not only perfect for relaxation but also offer various water sports and adventure activities. The backwaters of Kerala, especially in places like Alappuzha (Alleppey) and Kumarakom, are an iconic feature of the state’s landscape. Houseboats cruising through the serene, lush green waters offer a unique and tranquil experience. These backwaters are interlinked with canals, rivers, and lakes, creating a labyrinthine network that visitors can explore while experiencing local village life.

- Mountains and Hill Stations: Kerala’s mountainous regions are a major draw for tourists, especially during the summer months when the cool climate provides a welcome respite. Munnar, with its sprawling tea plantations, Eravikulam National Park, and scenic landscapes, is a popular hill station. Other significant hill stations include Wayanad, Vagamon, and Ponmudi. These places offer trekking, nature walks, and opportunities to explore diverse flora and fauna.

- Wildlife Sanctuaries and National Parks: Kerala is a treasure trove of wildlife, with a network of wildlife sanctuaries and national parks spread across its terrain. The Periyar Tiger Reserve, located in Thekkady, is one of the most famous wildlife reserves in India, known for its elephants and tigers. Other notable wildlife destinations include the Silent Valley National Park, Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary, and Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary. These parks are ideal for nature lovers and wildlife enthusiasts, offering a variety of eco-tourism experiences such as safaris, bird watching, and trekking.

- Waterfalls: Kerala’s landscape is dotted with beautiful waterfalls, which are perfect for nature lovers. Athirappilly, often referred to as the “Niagara of India,” is the largest waterfall in Kerala and is located in the Thrissur district. Other popular waterfalls include Vazhachal, Meghamalai, and Palaruvi, all of which offer stunning views and opportunities for photography and relaxation.

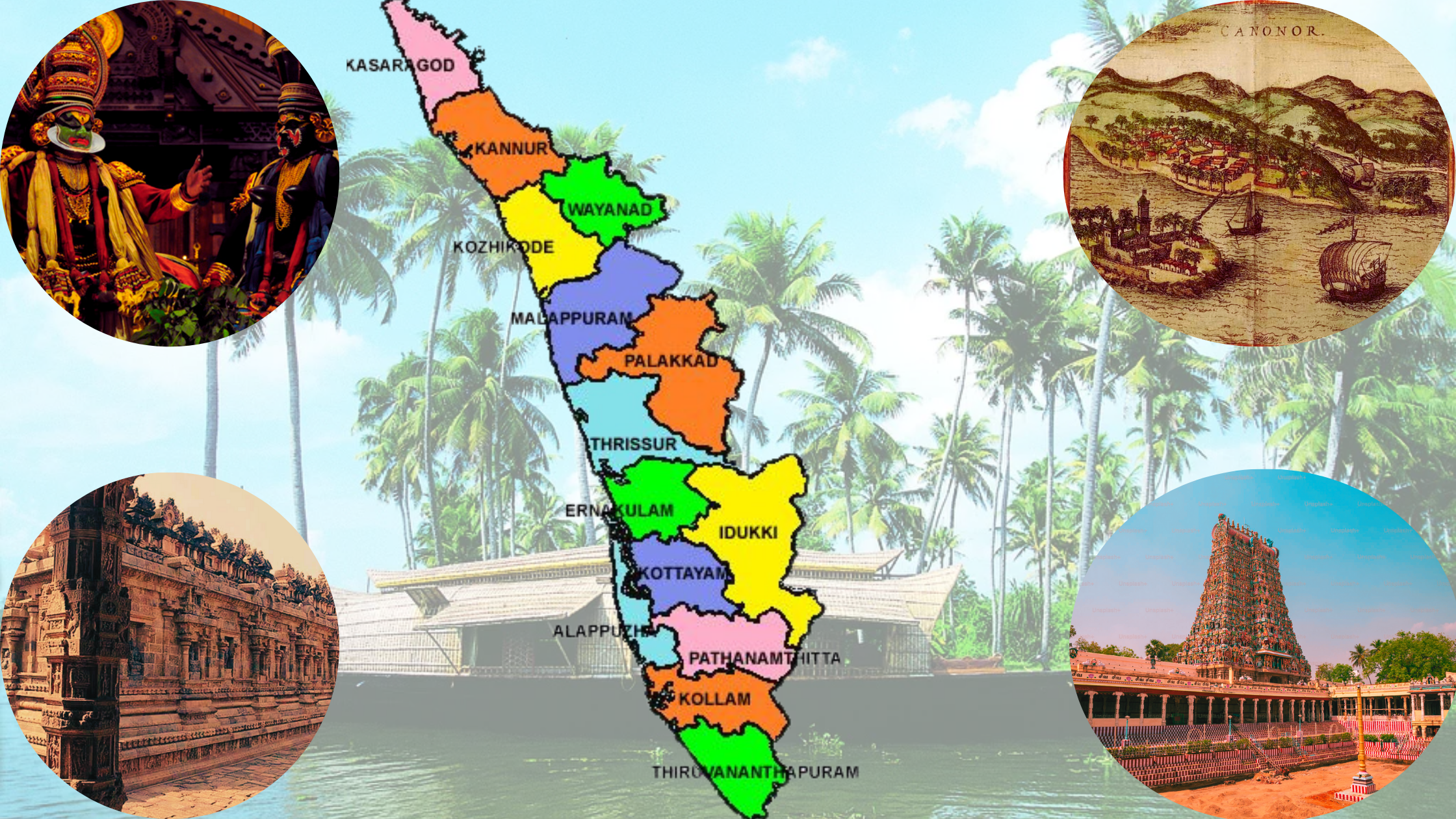

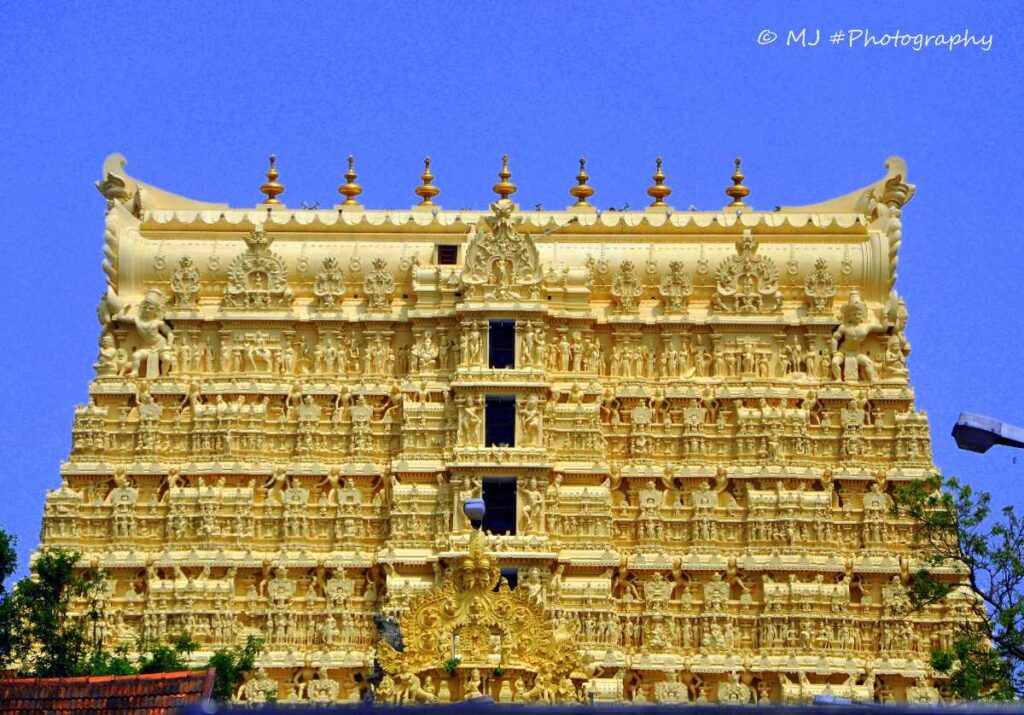

- Cultural Heritage and Religious Institutions: Kerala has a rich cultural and historical legacy, with ancient temples, churches, and mosques scattered throughout the state. Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram, Sree Krishna Temple in Guruvayur, and the St. Thomas Syro-Malabar Catholic Church are among the most revered religious places in Kerala. The state’s unique blend of Hindu, Christian, and Muslim cultures is reflected in its festivals, rituals, and architecture. Kerala also boasts of historic landmarks like the Mattancherry Palace and Padmanabhapuram Palace, showcasing its royal heritage.

- Ayurvedic Tourism: One of Kerala’s most famous attractions in recent decades has been Ayurvedic tourism. Ayurveda, the ancient system of natural healing, has found a global audience, and Kerala is regarded as the epicenter for authentic Ayurvedic treatments. The state has numerous wellness resorts, hotels, and specialized Ayurvedic centers that offer holistic treatments for physical well-being, mental peace, and rejuvenation. These treatments often include massages, herbal therapies, and yoga sessions. Since the 1990s, Kerala’s Ayurvedic tourism sector has grown exponentially, with both local agencies and the Kerala Tourism Department playing pivotal roles in promoting this unique offering. The tranquil environment, combined with the expertise in Ayurveda, attracts tourists looking to relax, heal, and rejuvenate.

- Ecotourism: Kerala’s diverse ecosystems make it a perfect destination for ecotourism. The state’s commitment to sustainability and preserving its natural beauty is reflected in its various eco-friendly initiatives. Sustainable tourism practices are integrated into its wildlife sanctuaries, beaches, and hill stations, where visitors are encouraged to appreciate nature responsibly. The state’s ecotourism destinations, such as Thattekad Bird Sanctuary, Muthanga Wildlife Sanctuary, and Parambikulam Tiger Reserve, offer an immersive experience in Kerala’s rich biodiversity.

Economic Impact of Tourism

Tourism is a crucial pillar of Kerala’s economy. In 2012, the state became one of the most prominent travel destinations globally, as evidenced by its inclusion in National Geographic’s list of “ten paradises of the world” and “50 must-see destinations of a lifetime.” Travel and Leisure magazine also hailed Kerala as one of the “100 great trips for the 21st century.” The state’s tourism sector has grown rapidly, providing employment for millions of people across the state.

By 2011, Kerala had crossed the 10-million mark in tourist arrivals, with the number continuing to rise each year. In 2018, over 16.7 million tourists visited the state, making it one of the fastest-growing travel destinations in the world. The revenue generated from tourism is a major contributor to Kerala’s state economy, fueling growth in other sectors like hospitality, transportation, and retail.

Promoting Kerala as a Global Brand

The government of Kerala recognized the importance of tourism as early as 1986, when it declared tourism an important industry. Since then, the Kerala Tourism Development Corporation (KTDC) has launched several successful marketing campaigns. The slogan “Kerala, God’s Own Country” has become globally recognized, cementing the state’s place on the world map as a premier travel destination. Kerala’s tourism is not just a local phenomenon but has reached international shores, with tourists from around the world flocking to the state for its unique offerings.

Conclusion

Kerala’s tourism industry continues to thrive thanks to its remarkable blend of natural beauty, rich cultural heritage, and sustainable tourism practices. Its beaches, backwaters, wildlife, Ayurvedic offerings, and rich cultural heritage ensure that it remains one of the most popular tourist destinations in India. With the state’s tourism industry growing year by year, Kerala’s global reputation as a top travel destination only seems to be getting stronger. The government and private agencies continue to work together to ensure that Kerala remains a key player in the global tourism market.