All About Nagaland

Nagaland, located in the northeastern region of India, shares borders with Arunachal Pradesh to the north, Assam to the west, Manipur to the south, and the Naga Self-Administered Zone of Myanmar to the east. Its capital is Kohima, while its largest city is the Chümoukedima–Dimapur urban area. Spanning an area of 16,579 square kilometers (6,401 sq mi), Nagaland has a population of 1,980,602, as per the 2011 Census, making it one of the least populated states in India.

History and Formation

Nagaland’s history is rich in ethnical myth passed down orally through generations. The Naga lines, known for their distinct languages, customs, and vesture, date back to at least the 13th century. The appearance of British social forces in the 19th century marked significant changes, with the British expanding their influence into the Naga Hills. After India’s independence in 1947, the question of the political status of the Naga Hills led to demands for independence by the Naga National Council (NNC), led by Zapa Philo.

This escalated into a fortified insurrection as the Indian government maintained that Nagaland was an integral part of the Indian Union. The prolonged conflict crowned in the creation of Nagaland as the 16th state of India on 1 December 1963.

Nagaland: Unveiling the Mystique of India’s Tribal Paradise

A democratically tagged government was established in 1964, bringing political stability to the region. Nagaland is a mountainous state, positioned between 95 ° and 94 ° eastern longitude and 25.2 ° and 27.0 ° north latitude. It’s home to the famed Dzeko Valley, located near Vaseema in the south. The state is rich in natural coffers similar as minerals, petroleum, and hydropower. Husbandry remains the dominant sector, contributing 24.6 to the frugality, alongside conditioning like forestry, tourism, real estate, and horticulture. Nagaland is inhabited by 17 major lines and several sub-tribes, each with unique customs, traditions, and languages.

The Naga lines are famed for their vibrant carnivals, most specially the Hornbill Festival, which showcases the state’s different culture, music, cotillion , and crafts.The state is a land of ancient traditions, where ethnical societies practice collaborative living and uphold strong artistic ties.Despite modernization, the lines have retained much of their traditional heritage, making Nagaland a symbol of artistic preservation.Nagaland’s frugality is heavily reliant on husbandry, primarily rehearsing subsistence husbandry.

In recent times, horticulture, cabin diligence, and tourism have gained elevation.The state’s coffers in petroleum and hydropower are seen as openings for unborn profitable development.Tourism is growing, driven by the state’s natural beauty, artistic carnivals, and literal spots.

Etymology

The term ‘Naga’ has ambiguous origins. Historical records suggest various interpretations:

- The Ahom Kingdom referred to the Nagas as “Noga” or “Naka”, meaning “naked”.

- The Meitei people called them “Hao”.

- Burmese references, such as “Nakas”, described them as “people with earrings” or pierced noses.

Before European colonization, the Nagas faced frequent raids from Burma, which included headhunting and capturing wealth and people. British records of the term ‘Naga’, derived from Burmese guides, have since been widely adopted.

History of Nagaland: From Ancient Times to Modernity

Ancient History

The origins of the Naga people are deeply rooted in antiquity, with their presence in northeastern India predating written history. The Naga tribes are believed to have migrated from Southeast Asia or possibly the Mongolian plateau. Linguistic and cultural evidence links them to Tibeto-Burman language groups. The Nagas established settlements across the rugged terrains of the Naga Hills, developing a unique tribal society characterized by village republics, clan-based governance, and elaborate customs.

Traditional Naga society was fiercely independent, with inter-tribal rivalries and “head-hunting” being significant cultural practices. The head-hunting rituals symbolized valor and were associated with animistic religious beliefs. By the 12th century, historical records such as the Mongkawng Chronicles mention the interactions between Naga tribes and neighboring states like the Ahoms in Assam. The Kingdom of Mongmao in the 14th century also claimed influence over parts of Naga territory, indicating the region’s historical importance.

British Administration

Colonial intervention began in earnest during the mid-19th century. British expeditions were initially met with resistance, as the fiercely autonomous tribes resisted external control. The British undertook punitive campaigns against villages that refused to align, including the notable Battle of Kirkum in 1851.

Missionaries played a significant role during this period, introducing Christianity in the late 19th century. Their efforts saw a gradual but profound transformation of Naga society, as many converted from animism to Christianity. By 1878, Kohima became the administrative headquarters, marking the formal inclusion of the Naga Hills into British India. Over time, British policies helped reduce inter-tribal conflicts, although resentment against colonial rule persisted.

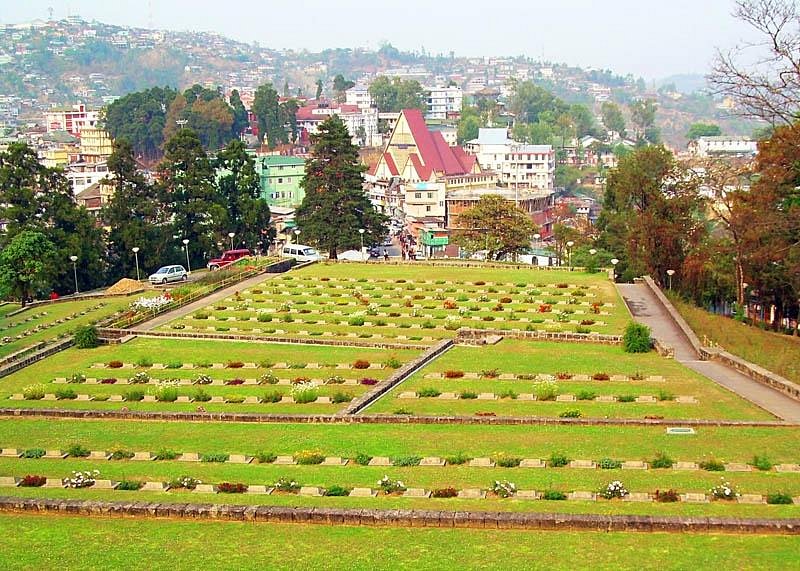

World War II

The Battle of Kohima during World War II was a decisive event, often referred to as the “Stalingrad of the East.” Fought between April and June 1944, the battle marked the Japanese army’s attempt to invade India via Burma. The British Indian forces, with local Naga support, repelled the Japanese forces, changing the course of the war in Southeast Asia. Today, the Kohima War Cemetery stands as a testament to the sacrifices made during this crucial battle.

Post-Independence History

After India’s independence in 1947, Nagaland’s integration into the Indian Union faced significant challenges. Tribal leaders, under the banner of the Naga National Council (NNC), demanded a separate sovereign state. This led to widespread insurgency and military intervention. The 16-Point Agreement of 1960 between the Indian government and Naga representatives eventually paved the way for Nagaland’s statehood in 1963.

Rebel activity persisted into the late 20th century, but peace initiatives by the Nagaland Baptist Church Council played a crucial role in mediating between the Indian government and Naga insurgent groups. Ceasefire agreements in the 1990s and 2000s have helped bring relative peace, though sporadic violence continues.

Geography and Climate of Nagaland

Geographical Features

Nagaland is a landlocked state in northeastern India, covering an area of 16,579 square kilometers. It shares borders with Assam to the west, Arunachal Pradesh to the north, Manipur to the south, and Myanmar to the east. The state’s terrain is predominantly hilly, with altitudes ranging from low-lying plains in Dimapur to peaks like Mount Saramati, which rises to 3,826 meters (12,552 feet).

The state is rich in rivers, including the Doyang, Dhansiri, and Tizu, which play a vital role in agriculture and ecology. Valleys like the Dzüko Valley are notable for their breathtaking landscapes and rare flora. The valley, located on the Nagaland-Manipur border, is often referred to as the “Valley of Flowers” of the Northeast.

Nagaland’s forests, which cover about 20% of the state, are a biodiversity hotspot, housing tropical and subtropical ecosystems. These forests are home to endemic plant and animal species that contribute to the state’s ecological richness.

Climate

Nagaland experiences a monsoon climate with distinct seasons. The rainy season, lasting from May to September, brings heavy rainfall, with annual precipitation ranging from 1,800 to 2,500 millimeters. This period is crucial for the state’s predominantly agrarian economy.

Winters, lasting from November to February, are dry and cold. Frost is common in high-altitude areas, and temperatures can drop to 4°C. Summers are short and relatively mild, with temperatures ranging from 16°C to 31°C, making the climate conducive for agriculture.

Flora and Fauna

Nagaland is a treasure trove of biodiversity, housing tropical and subtropical forests rich in flora and fauna. The state is home to 396 species of orchids, including the rare Rhynchostylis retusa (Kopou phool), which holds cultural and economic significance.

Wildlife in Nagaland is equally diverse. The forests support species such as:

- Mammals: Himalayan black bears, Bengal tigers, red pandas, and Indian leopards.

- Birds: The Blyth’s tragopan, Nagaland’s state bird, thrives in protected areas like Mount Japfü and Dzüko Valley.

- Reptiles and Amphibians: Various species adapted to tropical and subtropical conditions.

The Amur falcon migration is one of Nagaland’s most celebrated natural phenomena. Every year, hundreds of thousands of these migratory birds stop at the Doyang Reservoir during their journey from Siberia to Africa, earning Nagaland the moniker “Falcon Capital of the World.”

Urbanization and Resources

Urbanization Trends

Nagaland remains predominantly rural, with over 70% of its population residing in villages. The urban population is concentrated in towns like Kohima (the capital), Dimapur (the largest commercial hub), and Mokokchung (a cultural and educational center). The slow pace of urbanization reflects the state’s reliance on agriculture and traditional lifestyles.

Natural Resources

Nagaland has untapped reserves of petroleum, natural gas, limestone, and decorative stones. Recent studies have highlighted the potential for economic growth through mining and resource extraction. Efforts to develop sustainable industries, including eco-tourism and handicrafts, are ongoing to diversify the economy.

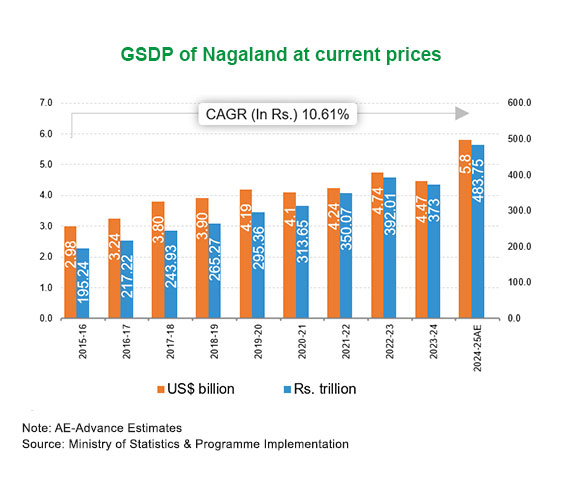

Economy of Nagaland

Nagaland’s economy is a mix of agriculture, forestry, small-scale industries, and service sectors. The Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) of Nagaland stood at approximately ₹12,065 crore (US$1.4 billion) during the 2011–12 fiscal year. Over the past decade, the GSDP growth rate was around 9.9% annually, resulting in significant improvements in per capita income. However, the state remains largely agrarian, with agriculture and forestry contributing a major portion of its GDP.

Agriculture and Livelihood

About 80% of Nagaland’s population depends on agriculture for their livelihood. Rice is the staple food and occupies approximately 80% of the cultivated land, emphasizing its importance to the state’s agrarian economy. Traditional farming methods, such as Jhum cultivation, are still widely practiced. While Jhum farming holds cultural significance, it has adverse environmental impacts, including deforestation, soil erosion, and reduced fertility. In recent years, there has been a shift toward terrace farming to combat these challenges, with a 4:3 ratio of Jhum to terraced cultivation.

Nagaland also grows plantation crops such as coffee, cardamom, and tea, especially in hilly terrains. These crops, though cultivated in small quantities, have immense growth potential. Oilseeds, another high-income crop, are becoming increasingly popular among farmers. Despite these efforts, farm productivity in Nagaland remains lower compared to other Indian states, necessitating the import of food grains from neighboring regions.

Emerging Sectors

Nagaland’s tourism sector has shown promise, especially after improvements in the law-and-order situation. Unique cultural experiences, festivals like the Hornbill Festival, and breathtaking landscapes have drawn attention to the state. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have also begun investing in eco-tourism, handicrafts, and hospitality industries.

The state’s mineral wealth, including coal, limestone, nickel, cobalt, chromium, and marble, offers immense potential for economic development. Oil exploration, resumed in the Chang pang and Tsori areas in 2014, is expected to further boost the economy. Nagaland’s literacy rate of 80.1% and the widespread use of English as the official language enhance the state’s potential to attract industries and improve skill development programs.

Natural Resources of Nagaland

Nagaland is rich in natural resources, with substantial reserves of minerals, forests, and hydroelectric potential. Key resources include coal, limestone, iron ore, nickel, chromium, and marble, which are largely untapped. Efforts to harness these resources, including oil and gas exploration, have gained momentum in recent years.

Mineral Wealth

Coal mining has been a traditional activity in Nagaland, though primarily on a small scale. Recent initiatives have aimed to commercialize these operations to boost revenue and create employment. The state also has significant limestone reserves, which hold potential for cement and construction industries. Other valuable minerals like nickel and cobalt are critical for industries like electronics and renewable energy.

In 2014, Nagaland resumed oil exploration in the Changpang and Tsori areas under the Wokha district, marking a turning point for its resource-based economy. The resumption was led by Metropolitan Oil & Gas Pvt. Ltd., following earlier disputes involving the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC). If fully realized, oil and gas reserves could substantially enhance Nagaland’s revenue base.

Forests and Biodiversity

Forests cover around 52% of Nagaland’s area, hosting diverse flora and fauna. The state is home to tropical and subtropical ecosystems, which provide timber, medicinal plants, and other forest products. However, deforestation caused by Jhum cultivation poses a major threat to this resource. Sustainable forestry initiatives and community-based conservation efforts are being promoted to address this issue.

Hydroelectric Potential

Nagaland has significant untapped hydroelectric potential due to its hilly terrain and numerous rivers, such as the Doyang, Dhansiri, and Tizu. Despite having the infrastructure for power distribution, the state faces a significant energy deficit, producing only 87.98 MU against a demand of 242.88 MU. Harnessing its hydroelectric resources could transform Nagaland into a power-surplus state, enabling it to supply energy to neighboring regions.

Transportation in Nagaland

Nagaland’s rugged terrain and mountainous geography pose significant challenges to transportation infrastructure development. However, the state has made strides in connecting remote areas and improving accessibility for trade, tourism, and daily commutes. The transportation network relies primarily on roadways, supplemented by limited rail and air connectivity.

Roadways

Roads are the lifeline of Nagaland’s transport system, with over 15,000 kilometers of surfaced roads crisscrossing the state. Despite being one of the better-connected states in the northeastern region, road maintenance remains a persistent challenge due to frequent landslides, heavy rainfall, and poor quality construction.

Several National Highways (NH) pass through Nagaland, forming the backbone of inter-state and intra-state connectivity. Key highways include:

- NH 2: Connecting Kohima to Dimapur and Imphal.

- NH 29: Running from Dabaka in Assam to Kohima, further linking Nagaland to Manipur.

- NH 129A: Linking Dimapur to Jalukie and Peren.

Nagaland is also part of the international Asian Highway Network, with AH1 and AH2 passing through the state, enhancing its strategic significance as a gateway to Southeast Asia.

Railways

Rail connectivity in Nagaland is limited, with Dimapur being the sole major railway station. This station connects the state to important cities like Guwahati, Kolkata, and Delhi. Efforts are underway to extend rail services to Kohima, which would greatly improve accessibility and reduce travel costs.

Airways

Nagaland’s air connectivity revolves around Dimapur Airport, located 7 kilometers from Dimapur and 70 kilometers from Kohima. The airport serves as a hub for domestic flights to Kolkata, Guwahati, Imphal, and Dibrugarh. Its asphalt runway, 2290 meters in length, accommodates small and medium-sized aircraft. However, expanding air connectivity remains a priority to boost tourism and business opportunities.

Festivals of Nagaland: A Celebration of Life and Nature

Nagaland is aptly called the “Land of Festivals” because its cultural ethos revolves around celebrations that highlight unity, tradition, and agriculture. Each of the 17 major tribes in Nagaland has unique festivals, reflecting their agrarian lifestyles and spiritual beliefs. These festivals often involve elaborate rituals, colorful attire, traditional dances, and communal feasts.

For instance, the Angami tribe celebrates Sekrenyi in February, marking the purification and renewal of life. It involves a ritual bath, community prayers, and traditional games to cleanse the soul and body for the coming year. Similarly, the Ao tribe holds Moatsü in May to mark the end of the sowing season, offering thanks to the gods for their blessings.

The festivals are more than just celebrations; they are a means of preserving and passing down oral traditions, ancient practices, and community values. The Lotha tribe’s Tokhü Emong, held in November, is a thanksgiving festival emphasizing forgiveness and harmony. During this time, tribal elders narrate folktales to younger generations, ensuring cultural continuity.

Nagaland also observes Christian festivities such as Christmas and Easter, given the state’s predominantly Christian population. This blend of traditional and modern celebrations underscores the state’s cultural diversity.

While each tribe celebrates its unique festivals, the Hornbill Festival, launched in 2000, brings all tribes together on one platform, promoting unity and showcasing Nagaland’s rich cultural heritage. The spirit of these festivals lies in fostering unity, respect for traditions, and appreciation for the blessings of nature.

Hornbill Festival: Nagaland’s Grand Cultural Extravaganza

The Hornbill Festival is one of India’s most prominent cultural festivals, held annually in December. Organized by the Government of Nagaland at Kisama Heritage Village, this week-long event celebrates the state’s diversity and artistic expression.

The festival is named after the hornbill bird, a revered figure in Naga folklore symbolizing prosperity and grandeur. All 17 tribes participate, donning traditional attire, performing dances, and singing folk songs. The vibrant displays of tribal life, customs, and art attract thousands of domestic and international tourists.

Key highlights of the festival include:

- Cultural Performances: Tribal dances, folk music, and traditional storytelling take center stage.

- Art and Craft Exhibition: Skilled artisans showcase intricate wood carvings, pottery, and textiles.

- Sports and Games: Traditional sports like Kene (Naga Wrestling) and Aki Kiti (Sümi Kick Fighting) add excitement.

- Culinary Delights: Food stalls serve authentic Naga dishes, including smoked meats, fermented bamboo shoots, and dishes prepared with the fiery Naga Mircha (King Chilli).

Modern attractions like the Hornbill National Rock Contest, WWII Vintage Car Rally, and Hornbill Literature Festival add to its charm. The festival not only boosts tourism but also fosters inter-tribal harmony and cultural preservation.

Traditional Sports: A Display of Strength and Skill

Nagaland’s traditional sports are deeply intertwined with its tribal culture, reflecting the community’s spirit and values. Among the most popular is Kene, or Naga wrestling, a sport that tests strength, technique, and agility. Originating from the Angami tribe, Kene is now a pan-Naga tradition where wrestlers compete to pin their opponents to the ground. The sport is so popular that annual tournaments attract large audiences, including visitors from outside the state.

Aki Kiti, practiced by the Sümi tribe, is another fascinating traditional sport. Also known as Sümi kick fighting, it involves using only the soles of the feet to attack and defend. Unlike wrestling, Aki Kiti was historically used to settle disputes or restore honor without resorting to bloodshed. Today, it is a celebrated part of Sümi festivals and cultural events.

Beyond these, traditional archery and indigenous games like spear-throwing and tribal relay races are integral to festivals. These sports not only serve as entertainment but also strengthen community bonds and preserve ancient traditions.

Cuisine of Nagaland: A Journey Through Flavor

Nagaland’s cuisine is a delightful exploration of bold flavors and traditional cooking techniques. The state’s food is deeply rooted in its agrarian lifestyle, emphasizing fresh, locally sourced ingredients. Rice is the staple, often accompanied by smoked or fermented meat, bamboo shoots, and vegetables.

One of the most iconic ingredients is the Naga Mirchi (King Chili), among the hottest chilies in the world. This fiery chili is used to prepare pickles, curries, and chutneys that accompany meals. Fermentation is another hallmark of Naga cooking. Axon (fermented soybean) and bamboo shoots add a tangy depth to dishes.

Education in Nagaland: Building a Literate Society

Nagaland has made significant strides in education, achieving a literacy rate of 80.1%, which is higher than the national average. Education in Nagaland is primarily conducted in English, the state’s official language. This emphasis on English education aligns with the state’s vision of fostering global communication and opportunities for its students.

Key Institutions:

Nagaland is home to several prominent institutions catering to diverse fields of study:

- Nagaland University:

- A central university with campuses in Lumami, Kohima, and Medziphema.

- Offers undergraduate, postgraduate, and doctoral programs across disciplines like arts, science, commerce, and agriculture.

- National Institute of Technology (NIT):

- One of India’s premier engineering institutions, located in Dimapur.

- Provides specialized programs in technology and engineering, contributing to the state’s technical workforce.

- St. Joseph University:

- A private university offering programs in management, humanities, and sciences.

- Focuses on research and innovation alongside traditional academics.

- Medical and Veterinary Colleges:

- The Nagaland Institute of Medical Sciences and Research in Kohima is dedicated to producing skilled healthcare professionals.

- The College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry in Jalukie aims to improve agricultural and livestock practices.

Nagaland’s education policy emphasizes skill-based training to meet the demands of modern industries. Programs in engineering, medicine, veterinary sciences, and arts ensure that students are well-equipped to pursue careers both locally and internationally. Scholarships, outreach programs, and collaborations with institutions outside the state further enhance opportunities for students.

Tourism in Nagaland: Tapping into Cultural Richness

Nagaland’s breathtaking landscapes and vibrant cultural heritage make it one of India’s most unique and promising tourist destinations. Often referred to as the “Switzerland of the East”, the state combines natural beauty with cultural depth to attract tourists from around the world.

Major Attractions:

- Cultural Festivals:

- The state’s highlight is the Hornbill Festival, a week-long celebration held in December that showcases the traditions, music, and cuisine of all 17 tribes of Nagaland.

- Tribal festivals like Sekrenyi (Angami), Tokhü Emong (Lotha), and Moatsü (Ao) offer immersive experiences into the region’s traditions.

- Scenic Landscapes and Adventure Tourism:

- The rolling hills, lush forests, and pristine rivers provide ample opportunities for trekking, camping, and wildlife photography.

- Popular trekking destinations include Dzukou Valley, known for its natural beauty and seasonal flowers, and Japfu Peak, offering panoramic views of the region.

- Wildlife Sanctuaries:

- Sanctuaries like Ntangki National Park house diverse flora and fauna, including rare and endangered species like the hoolock gibbon.

- Birdwatchers are drawn to the migratory spectacle of Amur falcons in Nagaland during their annual journey.

- Handicrafts and Cultural Exhibitions:

- Nagaland is renowned for its traditional crafts, including intricate beadwork, bamboo products, and handwoven textiles.

- Tourists can visit local markets and cultural centers to buy authentic souvenirs while supporting local artisans.

Responsible Tourism:

Nagaland is pioneering socially responsible tourism, involving local councils, youth groups, and elders in its development. This approach ensures that tourism growth respects the cultural and ecological balance of the state. Villages like Khonoma, Asia’s first green village, are leading examples of sustainable tourism, blending eco-preservation with cultural preservation.

By tapping into its rich cultural heritage and natural resources, Nagaland is positioning itself as a hub for experiential tourism. The state’s focus on infrastructure development, guided tours, and community involvement ensures a fulfilling experience for tourists while fostering economic growth for local communities.