All about West Bengal

West Bengal, located in the eastern region of India, is a state rich in history, culture, and economic significance. It shares its borders with Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan, as well as Indian states including Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar, Sikkim, and Assam. Spanning an area of 88,752 km² and housing a population of over 102 million (as of 2023), West Bengal is the fourth-most populous and thirteenth-largest state by area in India. Its capital, Kolkata, is a cultural and intellectual hub, and ranks as India’s third-largest metropolis.

The state boasts diverse geography, including the Darjeeling Himalayan hills, the Ganges delta, the Rarh region, the Sundarbans, and the Bay of Bengal coast. West Bengal is famous for its ecological and cultural landmarks, including three World Heritage sites, such as the Sundarbans National Park, a UNESCO-listed mangrove forest and home to the Bengal tiger.

West Bengal the Rich and Vibrant Culture, History.

West Bengal has a rich historical narrative, featuring successive empires, cultural advancements, and intellectual movements. Ancient Bengal was ruled by Vedic Janapadas, and later by empires like the Mauryas, Guptas, and Palas. The region witnessed Islamic influence with trade links to the Abbasid Caliphate and the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate. The Bengal Sultanate emerged as a dominant trading power, often regarded as one of the world’s wealthiest regions during its time. It was later annexed by the Mughal Empire and became semi-autonomous under the Nawabs of Bengal, a period marked by proto-industrialization and economic prosperity.

West Bengal’s political landscape transformed under British rule. The Battle of Buxar (1764) led to its annexation into the Bengal Presidency under the British East India Company. From 1772 to 1911, Kolkata served as the capital of British India, fostering early exposure to Western education and reform. The Bengali Renaissance emerged during this period, spearheaded by icons like Rabindranath Tagore, who won India’s first Nobel Prize in Literature.

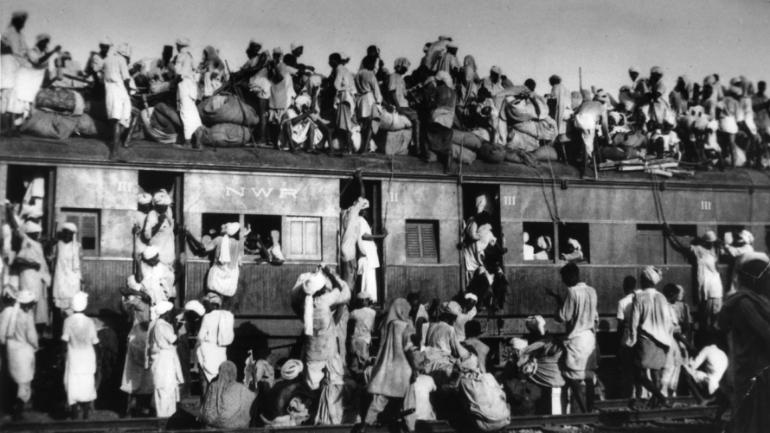

The Partition of Bengal in 1947, along religious lines, created West Bengal, a Hindu-majority Indian state, and East Bengal, which later became Bangladesh. The state absorbed large waves of refugees, reshaping its demography and politics. Post-independence, West Bengal became a center for India’s independence movement and social reform but also experienced political turbulence, especially during the communist rule from 1977, which hindered economic growth.

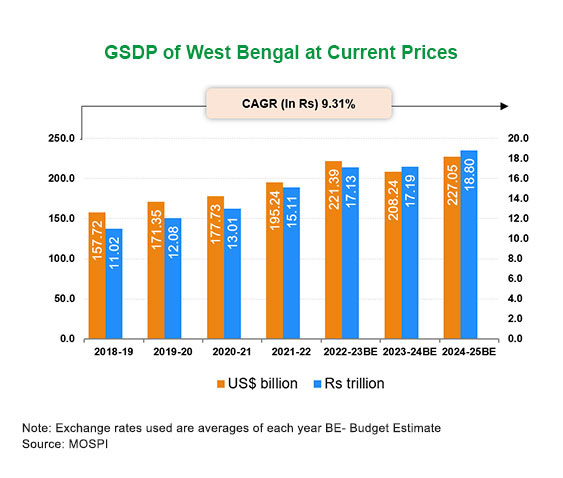

In recent years, the state has rebounded with a growing economy, though challenges like infrastructure development and foreign investment persist. As of 2023–24, West Bengal’s Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) is estimated at ₹17.19 lakh crore (US$210 billion), making it the sixth-largest state economy in India.

The Bengali people, predominantly Hindu, form the state’s primary ethnic group, with Islam as the second-largest religion. The Bengali language is widely spoken, alongside cultural traditions rooted in literature, music, film, and art. The state’s vibrant festivals, including Durga Puja, attract global attention.

Despite its vibrant cultural and economic contributions, West Bengal faces challenges such as a lower Human Development Index (HDI) ranking and a significant state debt of ₹6.47 lakh crore. However, its natural and cultural wealth continues to make it a major tourist destination, ranking as India’s third-most visited state globally. The government is focused on improving infrastructure, easing land acquisition policies, and encouraging investments to further its growth.

The name Bengal is believed to derive from “Bang,” a Dravidian tribe that settled in the region around 1000 BCE. The native name, Paschim Banga, translates to “Western Bengal” in Bengali. Proposals to rename the state to “Bengal” or “Bangla” have faced political and bureaucratic hurdles, with concerns over potential confusion with neighboring Bangladesh.

West Bengal remains a state of contrasts—deeply rooted in tradition yet striving to embrace modernity, balancing its historical legacy with contemporary aspirations.

History of Bengal: A Journey Through Time

Ancient and Classical Periods

Stone Age tools discovered in Bengal reveal human presence dating back 20,000 years, challenging earlier assumptions by 8,000 years. The Mahabharata, an Indian epic, identifies Bengal as part of the Vanga Kingdom. Early Vedic realms like Vanga, Rarh, Pundravardhana, and Suhma thrived in the region. Ancient Greek texts (circa 100 BCE) reference a prosperous land named Gangaridai, situated at the Ganges’ delta, known for its robust trade relations with Suvarnabhumi (modern Southeast Asia). According to the Mahavamsa, Prince Vijaya of Vanga founded the Sinhala Kingdom in Sri Lanka around 543 BCE.

The Kingdom of Magadha, established in the 7th century BCE, encompassed present-day Bihar and Bengal. Renowned as one of ancient India’s four main kingdoms, Magadha flourished during the eras of Mahavira (Jainism) and Gautama Buddha (Buddhism). The Maurya Empire under Ashoka expanded across South Asia, including Afghanistan and Balochistan, while the Gupta Empire (3rd–6th century CE) marked a golden age of art, science, and culture.

After the Gupta Empire’s decline, Bengal saw the rise of Vanga, Samatata, and Gauda Kingdoms, culminating in the reign of King Shashanka in the 7th century. Shashanka, a notable yet controversial figure, founded the Gauda Kingdom and faced criticism in Buddhist texts for alleged persecution of Buddhists, including destroying the Bodhi Tree at Bodhgaya. His rule gave way to the Pala Dynasty (8th–12th century), which championed Buddhism and global trade, followed briefly by the Hindu Sena Dynasty.

During the early 11th century, Rajendra Chola I from South India invaded parts of Bengal. Meanwhile, Islam made its first inroads through trade with the Abbasid Caliphate, setting the stage for the region’s significant cultural transformation.

Medieval and Early Modern Periods

The 13th century saw Bengal’s integration into the Delhi Sultanate under Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, establishing mosques, madrasas, and Islamic institutions. By 1352, the Bengal Sultanate emerged as a powerful entity, recognized by Europeans as one of the wealthiest trading nations. However, Bengal’s independence ended in 1576 when it was absorbed into the Mughal Empire.

During Mughal rule, Bengal became a hub of commerce and culture. While feudal lords governed locally, semi-autonomous Nawabs eventually rose to power. Islam Khan, a prominent Mughal general, consolidated Mughal authority. Bengal also witnessed Hindu resistance, exemplified by Raja Ganesha’s uprising and the establishment of Hindu states under leaders like Pratapaditya of Jessore and Raja Sitaram Ray of Bardhaman.

Under the Nawabs of Murshidabad, Bengal experienced early signs of the Industrial Revolution with advancements in textile production and trade. The Koch Dynasty in northern Bengal thrived through the 16th and 17th centuries, enduring Mughal dominance and later transitioning into the British colonial period.

Colonial Period: A Turning Point in Bengal’s History

Bengal’s history took a pivotal turn during the colonial period, beginning with the arrival of European traders in the late 15th century. The British East India Company established dominance after its victory over Siraj ud-Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal, in the Battle of Plassey (1757). This marked the start of British rule in Bengal. Later, the Treaty of Allahabad (1765), signed after the British defeated Indian forces in the Battle of Buxar (1764), granted the company the right to collect revenue in Bengal.

The Bengal Presidency, established in 1765, encompassed a vast area stretching from the Ganges Delta to the Himalayas. However, this period saw immense suffering, including the devastating Bengal Famine of 1770, which claimed millions of lives, largely attributed to the exploitative tax policies of the East India Company.

In 1773, Calcutta (now Kolkata), the company’s headquarters, was declared the capital of British India, cementing Bengal’s political and economic significance. The failed Indian Rebellion of 1857, which began near Calcutta, led to a transfer of power from the East India Company to the British Crown, marking the advent of direct rule under the Viceroy of India.

Cultural Renaissance and Resistance

The Bengal Renaissance became a hallmark of this era, spearheaded by socio-cultural reform movements like the Brahmo Samaj, which sought to modernize society. The region’s intellectual resurgence significantly influenced art, education, and politics. However, Bengal also faced attempts at division, with the controversial Partition of Bengal in 1905, which was annulled in 1911 due to widespread opposition.

The horrors of World War II brought another tragedy: the Great Bengal Famine of 1943, which killed three million people. This was a period of heightened revolutionary activity, with groups like Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar playing crucial roles in the Indian independence struggle. Subhas Chandra Bose, a prominent leader from Bengal, led the Indian National Army (INA) in a valiant effort to overthrow British rule, though it was eventually defeated.

Independence and Aftermath

The independence of India in 1947 came with the partition of Bengal along religious lines. The western part became West Bengal, part of India, while the eastern region became East Bengal, a province of Pakistan, later achieving independence as Bangladesh in 1971. The partition led to massive population displacement and refugee crises, shaping the socio-economic and political landscape of West Bengal for decades.

In 1950, the Princely State of Cooch Behar merged with West Bengal, followed by the integration of Chandannagar, a former French enclave, in 1955. These events, along with the merging of portions of Bihar, expanded West Bengal’s territory.

Challenges and Revival

West Bengal faced significant challenges during the 1970s and 1980s. A violent Maoist movement (Naxalism), severe power shortages, and economic stagnation led to widespread deindustrialization. The influx of refugees from the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 further strained resources. However, the Left Front government, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), took charge in 1977 and governed for three decades.

Despite political turbulence, the state’s economy began recovering in the mid-1990s with the advent of economic liberalization and growth in the IT and services sectors. However, issues like industrial land disputes led to political upheaval, culminating in the 2011 electoral defeat of the Left Front.

Today, West Bengal continues to recover from its tumultuous past. While improvements in education and employment have been made, challenges like healthcare inadequacies, infrastructure gaps, and social unrest remain key areas for development.

Geography of West Bengal: A Land of Diverse Landscapes

West Bengal, located on India’s eastern bottleneck, spans from the Himalayas in the north to the Bay of Bengal in the south, covering an area of 88,752 square kilometers (34,267 square miles). The state’s geography is a tapestry of varied landscapes, including towering mountains, fertile plains, riverine deltas, and coastal mangroves.

Northern Highs: The Darjeeling Himalayan Region

The northernmost part of West Bengal is nestled within the Eastern Himalayas. This region is home to Sandakfu, the state’s highest peak at an elevation of 3,636 meters (11,929 feet). The Darjeeling Himalayan hill region is renowned for its scenic beauty, tea plantations, and biodiversity. Below the hills lies the Terai region, a narrow strip that transitions into the North Bengal plains, an agriculturally rich zone.

The Ganges Delta and Sundarbans

As the northern plains extend southward, they merge into the Ganges Delta, one of the world’s largest river deltas. This area is characterized by intricate networks of rivers and creeks. The Sundarbans, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, forms a unique mangrove ecosystem and is home to the Royal Bengal Tiger. This region is a hallmark of West Bengal’s geography, contributing to its ecological significance and tourism.

Plateaus, Plains, and Coastal Regions

The Rarh region lies between the Ganges Delta to the east and the western plateau. This undulating landscape is marked by red lateritic soils. The western plateau and highlands are geologically distinct, hosting rivers like the Damodar, Ajay, and Kangsabati. In the extreme south lies a narrow coastal belt, which meets the Bay of Bengal.

River Systems: Lifelines of Bengal

The rivers of West Bengal play a pivotal role in shaping its geography and sustaining its population. The Ganges, the state’s most prominent river, splits into two branches:

- Padma River: Flows into Bangladesh.

- Bhagirathi-Hooghly River: Travels through West Bengal, sustaining its economic and cultural heartlands.

The Farakka Barrage diverts water into the Hooghly via a feeder canal, a subject of ongoing water-sharing disputes between India and Bangladesh.

Northern Bengal is crisscrossed by rivers like the Teesta, Torsa, Jaldhaka, and Mahananda, while the western plateau is drained by the Damodar, once known as the “Sorrow of Bengal” due to its devastating floods. The Damodar Valley Project has now tamed its flow with several dams. Despite this, arsenic contamination of groundwater remains a pressing issue, affecting over 10 million people.

Climate: Tropical Variance

West Bengal’s climate ranges from tropical savanna in the south to humid subtropical in the north. The state experiences four main seasons:

- Summer: March to May; temperatures often reach 38–45°C (100–113°F). The delta regions are humid, while the western highlands have drier summers.

- Monsoon: June to September; the Bay of Bengal monsoon brings heavy rains, with districts like Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, and Cooch Behar receiving over 250 cm (98 inches) annually. Coastal areas often face cyclonic storms during this season.

- Autumn: October to November; marked by clear skies and mild weather.

- Winter: December to January; plains experience mild winters with average temperatures around 15°C (59°F), while the Darjeeling region witnesses harsh cold and occasional snowfall.

Natural Challenges

West Bengal’s geography presents several challenges:

- Flooding during monsoons disrupts daily life in low-lying areas.

- Cyclonic storms in the coastal regions lead to widespread damage.

- River pollution, particularly in the Ganges, has emerged as a critical issue due to waste dumping.

Despite these challenges, West Bengal’s diverse geography remains one of its greatest strengths, fostering agriculture, biodiversity, and a rich cultural heritage.

Flora and Fauna of West Bengal: A Treasure of Biodiversity

West Bengal is home to a rich diversity of flora and fauna, thanks to its varied geography ranging from the Himalayas in the north to the Sundarbans mangrove forests in the south. The state’s natural heritage includes forests, wildlife sanctuaries, and national parks that support a wide array of species and ecosystems.

Forests: A Green Canopy Across the State

As per the India State of Forest Report 2017, West Bengal has a total forested area of 16,847 square kilometers (6,505 square miles), constituting approximately 18.93% of the state’s geographical area. Though this is below the national average of 21.23%, the forests in West Bengal play a critical role in sustaining biodiversity and providing ecological services.

The forested regions can be categorized as follows:

- Reserves: 59.4%

- Protected Forests: 31.8%

- Unclassed Forests: 8.9%

The southern part of the state includes two distinct vegetative regions:

- Gangetic Plains: Fertile lands with alluvial soil, supporting a variety of agricultural and native vegetation.

- Sundarbans Mangrove Forests: The largest mangrove forest in the world, home to the iconic sundari tree (Heritiera fomes) from which the forest derives its name.

The sal tree (Shorea robusta) dominates the forests of the western region, while the coastal vegetation in Purba Medinipur features Casuarina trees, which protect the coastline.

In the northern highlands, vegetation changes with elevation:

- Dooars: Dense forests of sal and tropical evergreen species.

- Darjeeling Hills (1,000–1,500 meters): Subtropical and temperate forests with oaks, rhododendrons, and conifers

Wildlife: A Haven for Rare and Endangered Species

West Bengal hosts a remarkable variety of wildlife across its fifteen wildlife sanctuaries and five national parks, which together cover 3.26% of the state’s geographical area.

National Parks of West Bengal

- Sundarbans National Park: A UNESCO World Heritage Site and home to the endangered Royal Bengal Tiger.

- Buxa Tiger Reserve: Known for tigers, leopards, and elephants.

- Gorumara National Park: Famous for the Indian rhinoceros.

- Neora Valley National Park: A biodiversity hotspot sheltering species like the red panda.

- Singalila National Park: High-altitude forests home to rare animals like the red panda, barking deer, and birds like the kalij pheasant.

Key Wildlife Species

The state supports numerous mammal species, including:

- Indian Rhinoceros: Found in the grasslands of northern Bengal.

- Indian Elephant: Frequently seen in forests and wildlife sanctuaries.

- Royal Bengal Tiger: The star attraction of the Sundarbans.

- Leopards and Deer: Common across forested regions.

- Gaur and Crocodiles: Inhabit the foothills and river ecosystems.

The Sundarbans Biosphere Reserve not only conserves Bengal tigers but also shelters endangered species like the Gangetic dolphin, river terrapin, and estuarine crocodile. Additionally, the mangroves act as a natural nursery for fish, supporting marine biodiversity along the Bay of Bengal.

During winter, the wetlands of the state attract migratory birds, making it a paradise for birdwatchers.

Conservation Efforts

West Bengal’s ecological diversity faces challenges like deforestation, habitat loss, and human-wildlife conflict. However, initiatives like tiger conservation in the Sundarbans, and protection measures for rare species like the red panda and Gangetic dolphin, underscore the state’s commitment to preserving its natural heritage.

With its lush forests, unique wildlife, and dedicated conservation efforts, West Bengal remains a vital hub of biodiversity, offering countless opportunities for eco-tourism and environmental research.

West Bengal’s Governance and Politics

West Bengal’s political and administrative framework reflects the complex interplay between its historical legacy, socio-economic challenges, and regional aspirations. Below is an elaboration of the state’s electoral history, governance policies, and their broader impact.

Electoral History: A Tale of Political Transformations

- Pre-Independence Era and Early Years

- Before India’s independence in 1947, West Bengal’s political discourse was dominated by nationalist movements. The Indian National Congress (INC) was the key political force.

- Post-independence, the state experienced political stability under the INC, but regional challenges like refugee crises and industrial disputes began to surface.

- The Left Front Regime (1977–2011)

- The Communist Party of India (Marxist), heading the Left Front, came to power in 1977 under Jyoti Basu, who remains one of India’s longest-serving Chief Ministers (1977–2000).

- Achievements:

- Comprehensive land reforms under Operation Barga aimed to empower tenant farmers and boost rural productivity.

- Strengthened panchayati raj system, promoting grassroots democracy.

- Challenges:

- Stagnation in industrial development led to rising unemployment.

- Critics pointed to bureaucratic inefficiency and political violence.

- Leadership transitioned to Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee in 2000, who attempted to modernize the state’s economy through industrial initiatives. However, land acquisition controversies in Singur and Nandigram eroded public trust, leading to the Left Front’s electoral defeat in 2011.

- Mamata Banerjee and the Trinamool Congress Era (2011–Present)

- Mamata Banerjee’s All India Trinamool Congress (AITC) ended 34 years of Left rule in 2011.

- Her charismatic leadership and focus on welfare initiatives resonated with marginalized communities.

- 2016 and 2021 Elections:

- Despite emerging challenges from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Banerjee retained power, focusing on social welfare schemes like Kanyashree and Swasthya Sathi.

- Key Developments:

- Her government has promoted infrastructure development, particularly in rural connectivity and urban transit systems, including the Kolkata Metro expansion.

- Policies for women’s empowerment have been central, earning her international recognition.

- Rise of BJP as an Opposition Force

- The BJP has emerged as a major contender, significantly increasing its vote share during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections and the 2021 Assembly elections.

- Despite losing the 2021 Assembly polls, the BJP consolidated its presence in regions like North Bengal, challenging the AITC’s dominance.

Governance Policies and Impact

- Social Welfare Initiatives

- Kanyashree Prakalpa: A conditional cash transfer scheme for girls aimed at reducing dropouts and child marriages. Recognized by the United Nations, it has benefited millions of girls.

- Swasthya Sathi: A health insurance scheme offering coverage to low-income families, including cashless treatment.

- Sabooj Sathi: Distribution of bicycles to school students to promote education and mobility in rural areas.

- Infrastructure Development

- Urban development projects include flyovers, metro extensions, and housing initiatives in Kolkata.

- Rural infrastructure improvements under Pathashree-Rastashree aim to enhance road connectivity.

- Industrial Revival Efforts

- The Bengal Global Business Summit has attracted investments, but the state continues to face challenges in competing with industrial hubs like Gujarat and Maharashtra.

- Efforts to promote sectors like IT, textiles, and tourism are ongoing.

- Focus on Regional Aspirations

- Addressing demands for regional autonomy, the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA) was formed in 2012, granting administrative powers to the Darjeeling hills.

- However, occasional unrest over full statehood demands persists.

- Environmental Policies

- Conservation projects in the Sundarbans aim to protect the mangrove ecosystem and the endangered Bengal tiger.

- Sustainable development efforts include mitigating arsenic contamination and expanding forest cover.

Challenges in Governance

- Economic Concerns

- While welfare schemes have gained popularity, critics argue they strain the state’s fiscal resources.

- Industrial growth remains sluggish, with limited employment opportunities in manufacturing and IT sectors.

- Political Violence

- The state has a history of political clashes, especially between the ruling AITC and opposition parties.

- Electoral violence and governance issues have drawn criticism at both national and international levels.

- Regional Disparities

- While Kolkata and its surrounding areas see rapid development, rural and northern regions face economic stagnation.

- The Gorkhaland issue reflects deep-rooted dissatisfaction in the hills, requiring sensitive governance.

- Environmental Challenges

- Rising climate risks, such as cyclones and flooding in the Sundarbans, threaten both human lives and biodiversity.

- Pollution in the Ganges River and arsenic contamination of groundwater remain persistent problems.

Districts and Cities of West Bengal: A Detailed Overview

West Bengal is a state rich in geographical, cultural, and economic diversity. With its 23 districts and a variety of urban and rural landscapes, it encapsulates India’s blend of tradition and modernity. Below is a comprehensive analysis of its districts and key cities, emphasizing their demographic and economic significance.

Districts of West Bengal

West Bengal is divided into 23 districts, each administratively governed by a District Magistrate (DM) or Collector from the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) or West Bengal Civil Service (WBCS) cadre. These districts are further subdivided into sub-divisions, blocks, and panchayats, ensuring decentralized governance.

Demographics and Key Indicators of Districts

| District | Population | Growth Rate (%) | Sex Ratio | Literacy (%) | Density (per sq. km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North 24 Parganas | 10,009,781 | 12.04 | 955 | 84.06 | 2445 |

| South 24 Parganas | 8,161,961 | 18.17 | 956 | 77.51 | 819 |

| Purba Bardhaman | 4,835,432 | N/A | 945 | 74.73 | 890 |

| Paschim Bardhaman | 2,882,031 | N/A | 922 | 78.75 | 1800 |

| Kolkata | 4,496,694 | -1.67 | 908 | 86.31 | 24,306 |

| Murshidabad | 7,103,807 | 21.09 | 958 | 66.59 | 1334 |

| Howrah | 4,850,029 | 13.50 | 939 | 83.31 | 3306 |

| East Midnapore | 5,095,875 | 15.36 | 938 | 87.02 | 1081 |

| Darjeeling | 1,846,823 | 14.77 | 970 | 79.56 | 586 |

| Other districts | Continue to follow similar patterns of unique characteristics and challenges. |

Notable Features of Some Districts

- Kolkata

- The densest district with 24,306 people per square kilometer.

- Known as the cultural capital of India, it boasts high literacy and economic activity.

- North 24 Parganas

- The most populous district, known for its proximity to Kolkata and industrial hubs.

- South 24 Parganas

- A mix of urban and rural settings, including the Sundarbans mangrove forest, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

- Darjeeling

- Famous for its tea estates, scenic beauty, and Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA).

- East Midnapore

- High literacy and industrial zones like Haldia, contributing to the state’s economy.

Key Cities of West Bengal

The cities of West Bengal serve as economic, administrative, and cultural hubs. The state’s urban areas range from heritage-rich Kolkata to industrial Asansol and modern planned cities like New Town.

Major Cities

- Kolkata

- Capital and largest city of West Bengal.

- Hosts Raj Bhavan, Writers’ Building, and numerous historical landmarks.

- A hub for industries, information technology, and cultural institutions.

- Asansol

- Second-largest city and part of the Asansol-Durgapur Industrial Belt.

- Known for coal mining and steel production.

- Howrah

- A twin city to Kolkata, linked by the iconic Howrah Bridge.

- Major railway hub and industrial center.

- Siliguri

- Strategically located in the Siliguri Corridor (Chicken’s Neck), connecting the northeast to the rest of India.

- Known for tea, tourism, and trade with neighboring countries like Bhutan and Nepal.

- Durgapur and Kharagpur

- Both are industrial towns with significant contributions to steel production and education, housing institutions like IIT Kharagpur.

Planned Cities

- New Town and Bidhannagar (Salt Lake)

- Modern satellite cities developed to reduce pressure on Kolkata.

- New Town is a smart city project with IT parks, housing complexes, and green zones.

- Haldia

- A planned industrial city focusing on petrochemicals and port activities.

- Kalyani

- Known for its educational institutions and clean urban planning.

Economy of West Bengal Key Economic Drivers and Challenges

The economy of West Bengal has undergone several phases of growth and challenges since independence. The state’s economic landscape is diverse, with agriculture, industry, and services contributing to its overall economic activity. Over the years, West Bengal has experienced a mix of slowdowns and recoveries, particularly in sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and services.

Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) and Growth Trends

The Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) is a key indicator of economic growth, and West Bengal has seen significant fluctuations over the years. From 2004–2005, the NSDP at current prices has steadily increased. In 2004–2005, the NSDP stood at Rs 190,073 crores, growing to Rs 366,318 crores by 2009–2010. The growth was particularly notable between 2005 and 2010, where West Bengal saw a substantial economic rise. As of 2015, the Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) of West Bengal ranked sixth in India. From Rs 2,086.56 billion in 2004–05, the GSDP reached Rs 8,00,868 crores in 2014–2015 and Rs 10,21,000 crores in 2017–18.

The annual growth rate of GSDP has varied widely, from a low of 10.3% in 2010–2011 to a high of 17.11% in 2013–2014, showing considerable economic volatility in the state. Per capita income has been consistently lower than the national average, with per capita NSDP at Rs 78,903 in 2014–2015, though the growth rate of per capita income was strong, reaching 16.15% in 2013–2014.

Economic Composition and Sectoral Contributions

West Bengal’s economy is characterized by a large share of the services sector, which accounted for 66.65% of the state’s Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2015–2016. The state’s industrial share was at 18.51%, and agriculture contributed 4.84%. The dominance of the services sector highlights the state’s economic transition towards a service-oriented economy.

Agriculture remains crucial to the state, with rice, jute, sugarcane, and tea being the primary agricultural products. West Bengal is a major producer of Darjeeling tea and jute, making these industries essential for the state’s economy. The agricultural sector saw ups and downs, with significant growth in the 1980s followed by stagnation in the early post-independence years. However, by the late 20th century, food production increased, and the state now enjoys a surplus of food grains.

West Bengal also has a strong industrial base, particularly in areas such as engineering products, electronics, textiles, steel, and chemicals. The Durgapur-Asansol colliery belt is home to many steel plants, and the Haldia Port region serves as a hub for industrial activities. However, in the last few decades, there has been a gradual decline in industrial output, with the state’s industrial share in total national output shrinking from 9.8% in 1980–1981 to just 5% in 1997–1998.

Challenges in the Economic Landscape

Despite significant progress in certain areas, West Bengal’s economy faces multiple challenges. The state’s dependence on central government assistance has been a persistent issue, especially in sectors like food production and agriculture. The Indian Green Revolution bypassed the state, contributing to stagnation in food production in its early decades. However, recent years have seen improvements in food production and a surplus of grains, a testament to effective agricultural policies.

Several traditional industries, such as the jute industry and Hindustan Motors car manufacturing, have either shut down or scaled back operations. The Haldia Petrochemicals unit, once a key player in the state’s industrial output, experienced challenges, including financial constraints and political factors. Moreover, West Bengal’s tea industry has also been impacted by various financial and political issues, including labor strikes and management difficulties.

Another factor impacting the state’s economy is regional unrest. In 2017, the Gorkhaland agitation severely affected the state’s tourism industry, one of the growing sectors in recent years. Despite this setback, tourism—especially from neighboring Bangladesh—remains a significant contributor to the state’s economic growth.

Economic Revival and Future Prospects

In recent years, West Bengal has made concerted efforts to revive its economy by focusing on industrialization and improving the business climate. Initiatives such as promoting Kolkata as an investment destination and planning smart cities close to Kolkata have been steps in the right direction. The state government has been actively revamping its infrastructure, with large-scale roadway projects and urban development initiatives to attract foreign investments and enhance the overall economic environment.

West Bengal has successfully attracted about 2% of the foreign direct investment (FDI) in India over the last decade, indicating positive strides in improving its investment climate. Additionally, new industries such as leather complexes and engineering projects in Kolkata are helping diversify the state’s industrial portfolio. The state is also planning for modern smart cities, which will improve the living standards and economic activity in the surrounding regions.

With a focus on agriculture, manufacturing, and services, the future of West Bengal’s economy looks promising, though it still faces challenges that need to be addressed. By continuing to diversify its industrial base, improving infrastructure, and enhancing ease of doing business, the state can unlock its full economic potential in the years to come.

Transport in West Bengal: A Comprehensive Overview

West Bengal’s transport infrastructure plays a crucial role in the state’s economic growth and connectivity. The state boasts a vast network of roads, railways, airports, and water transport systems that facilitate both domestic and international travel. Over the years, significant developments have taken place in the transport sector, with notable improvements in urban mobility, regional connectivity, and international access.

Road Transport: Extensive Network and Connectivity

As of 2011, West Bengal had a road network extending over 92,023 kilometers (57,180 miles), making it one of the most connected states in India in terms of road infrastructure. This includes national highways, which stretch for 2,578 kilometers (1,602 miles), and state highways covering 2,393 kilometers (1,487 miles). The road density of the state stood at 103.69 kilometers per square kilometer, which is higher than the national average of 74.7 km/km², reflecting the state’s extensive and well-developed road infrastructure.

The Durgapur Expressway, a key highway connecting Kolkata with other parts of the state, plays an important role in easing traffic congestion and improving transportation efficiency. The expressway provides direct access to vital industrial zones, boosting economic activity in those areas. Additionally, government-owned transport corporations like the Calcutta State Transport Corporation and the South Bengal State Transport Corporation operate extensive bus services, offering affordable travel options to the public.

Private bus companies also operate across the state, while metered taxis and auto-rickshaws are commonly available for short-distance travel in cities. Cycle rickshaws and hand-pulled rickshaws are still in use, particularly in Kolkata, offering unique, eco-friendly transport options for short journeys.

Rail Transport: A Historic Network

The railway network in West Bengal is one of the most expansive in India, covering a total length of 4,481 kilometers (2,784 miles) as of 2011. Kolkata is home to the headquarters of Eastern Railway and South Eastern Railway, two of the prominent zones of the Indian Railways. The Kolkata Metro, India’s first underground railway system, is a testament to the state’s long history of rail transport. It connects different parts of the city, facilitating urban mobility and easing the burden on road transport.

In addition to the Kolkata Metro, the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a unique part of West Bengal’s railway heritage. This heritage railway continues to serve the Darjeeling region, attracting tourists and preserving a significant piece of the state’s history.

The Northeast Frontier Railway (NFR) serves the northern parts of the state, connecting Siliguri and surrounding areas to the rest of India. This region, with its mountainous terrain and lush landscapes, is a vital link for travelers heading to the Northeast of India and beyond.

Air Transport: Connecting West Bengal to the World

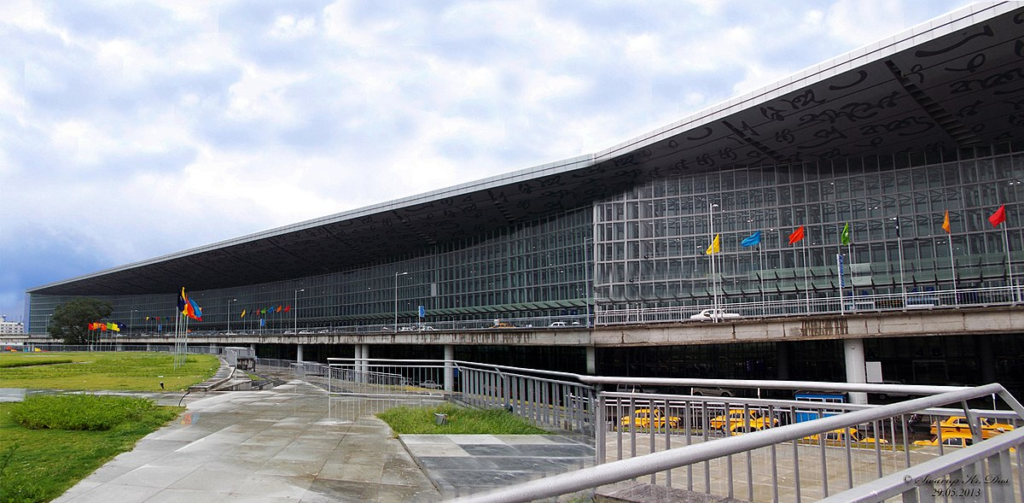

West Bengal’s air transport infrastructure is led by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose International Airport in Kolkata, which is the largest airport in the state. This airport serves as a hub for flights to and from Bangladesh, East Asia, Nepal, Bhutan, and North East India. The airport has undergone several expansions over the years to accommodate the growing number of passengers and international flights. It connects West Bengal to major global destinations, promoting both business and tourism in the region.

In addition to Kolkata’s international airport, Bagdogra Airport near Siliguri serves as a customs airport, providing international services to Bhutan and Thailand. It also facilitates domestic flights to other parts of India. Furthermore, Kazi Nazrul Islam Airport, located in Andal near Asansol-Durgapur, serves the twin cities with regular domestic flights. This airport was the first private sector airport in India and continues to be an important regional hub.

Water Transport: Kolkata Port and River Ferries

West Bengal is home to one of India’s major river ports, the Kolkata Port, which is managed by the Kolkata Port Trust. The port handles a significant amount of cargo both domestically and internationally. Kolkata is strategically located near the Hooghly River, which facilitates river transport, making it a vital hub for trade and logistics in the eastern region of India.

In addition to cargo services, the Kolkata Port offers passenger services to destinations such as Port Blair in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The Shipping Corporation of India operates regular cargo services from the port, connecting it with several ports in India and abroad.

In the Sundarbans area, river ferries are a primary mode of transport, connecting remote areas and offering scenic journeys through the region’s unique ecosystem. The Calcutta Tramways Company operates Kolkata’s famous trams, providing another form of historical and environmentally friendly transportation in the city.

Challenges and Future Developments in Transport Infrastructure

While West Bengal has made significant strides in improving its transport infrastructure, challenges still remain. The state’s urban transport systems, including the Kolkata Metro, face congestion issues due to the growing population and rapid urbanization. Efforts are underway to expand and modernize the metro network, with new lines and upgrades aimed at reducing overcrowding.

Additionally, while the road network is extensive, the state faces challenges in maintaining and modernizing roads in remote areas, where infrastructure development lags behind urban centers. Future investments in smart city projects and integrated transport systems are expected to alleviate these issues, improving the overall mobility and connectivity in the state.

Demographics of West Bengal: A Diverse and Growing Population

West Bengal, located in eastern India, is one of the most populous and culturally diverse states in the country. According to the 2011 census, the state had a population of 91.3 million, making it the fourth-most-populous state in India, contributing 7.55% to the nation’s total population. Over the decades, the state’s population has grown rapidly, although the growth rate has gradually slowed down in recent years. In this section, we will explore the historical population trends, ethnic diversity, language distribution, and other key demographic factors of West Bengal.

Historical Population Trends

The population of West Bengal has seen significant growth over the years. From 16.94 million in 1901, the state’s population steadily increased to 91.3 million in 2011. The growth rate has varied over time, with the 2001–2011 period seeing a growth rate of 13.93%, lower than the previous decade’s rate of 17.8%. This slowdown in population growth could be attributed to factors such as improved family planning, education, and economic changes.

The gender ratio of the state stands at 947 females per 1,000 males, reflecting a relatively balanced demographic structure. West Bengal also has a high population density of 1,029 people per square kilometre, making it the second-most densely populated state in India, after Bihar. The state’s literacy rate is 77.08%, which is higher than the national average of 74.04%.

Cultural and Ethnic Diversity

West Bengal is known for its rich cultural heritage and diverse ethnic communities. The majority of the population comprises Bengalis, with Bengali Hindus and Bengali Muslims forming the largest groups. There is also a significant number of Bengali Christians and a smaller community of Bengali Buddhists. In addition to these, various ethnic groups and indigenous communities contribute to the state’s cultural mosaic.

In the Darjeeling Hills, the population consists mainly of Gorkha communities, with Nepali (Gorkhali) being the dominant language spoken. Other indigenous communities in the region include the Sherpas, Bhutias, Lepchas, and Tamang, among others. Tibetan communities also live in this area, especially in the form of small but culturally significant populations.

Additionally, the Khortha language is spoken in the northern part of the state, particularly in Malda district, while Surjapuri, a mix of Maithili and Bengali, is spoken in parts of northern Bengal. Indigenous tribal groups such as the Santhal, Munda, Oraon, Bhumij, Lodha, Kol, and Toto make up a significant portion of the population in rural and tribal areas.

Language and Religious Diversity

West Bengal is home to a wide variety of languages, with Bengali being the official and most widely spoken language. In the Darjeeling Hills, Nepali is spoken by the Gorkha community, while other languages such as Hindi, Maithili, and Bhojpuri are common among various communities. Additionally, Marwari is spoken in certain pockets, particularly in the business community.

The state’s religious diversity is reflected in its population makeup. Bengali Hindus are the majority, followed by Bengali Muslims. West Bengal also has a small Christian community, as well as minority groups such as Jews, Parsis, Armenians, and Anglo-Indians, mainly concentrated in Kolkata. The Chinese community, primarily based in Kolkata’s Chinatown, represents one of the most unique ethnic minorities in the state.

Social Indicators and Living Standards

West Bengal has made significant progress in improving various social indicators. The life expectancy in the state stands at 70.2 years, which is higher than the national average of 67.9 years. The literacy rate of 77.08% is above the national average, indicating the state’s focus on education. However, poverty remains an issue in some areas, though the percentage of people living below the poverty line has declined from 31.8% in 2003 to 19.98% in 2013.

The state’s fertility rate of 1.6 is one of the lowest in India, comparable to that of Canada, indicating a trend toward smaller families and improved family planning. This is significantly lower than neighboring states like Bihar, which has a much higher fertility rate of 3.4.

Public Health and Hygiene

West Bengal has made strides in improving public health and sanitation. By September 2017, the state achieved 100% electrification, including remote villages in the Sunderbans, which had previously lacked power. Additionally, open defecation free (ODF) status has been achieved by 76 out of 125 towns in the state, with districts like Nadia, North 24 Parganas, Hooghly, and Bardhaman becoming ODF zones. Nadia was the first district to achieve this status in April 2015.

However, a study in three districts found that private healthcare services had a catastrophic impact on households, particularly for the poor. This highlights the need for better public healthcare provision to address poverty and ensure that illness does not exacerbate financial struggles.

Languages of West Bengal: A Linguistic Landscape

West Bengal is home to a rich linguistic diversity, with Bengali being the dominant language. The 2011 Census data shows that 86.22% of the population speaks Bengali as their first language. In addition to Bengali, other languages spoken in the state include Hindi (6.97%), Santali (2.66%), Urdu (1.82%), and Nepali (1.27%). The state has made significant strides in recognizing the importance of linguistic diversity, with various languages granted official status based on population percentages in certain regions.

- Bengali is the official language of the state and is spoken by the vast majority of the population. It is the language of literature, culture, and governance in West Bengal.

- Hindi has also been granted official status in areas where speakers exceed 10% of the population, reflecting the presence of Hindi-speaking communities in the state.

- Other languages such as Santali, Urdu, and Nepali have regional significance, with Nepali holding official status in the Darjeeling district subdivisions.

In 2012, a bill was passed to give official status to languages such as Odia, Punjabi, Santali, and Urdu in areas where these languages are spoken by more than 10% of the population. In 2019, Kamtapuri, Kurmali, and Rajbanshi were added to the list of official languages in specific regions. Telugu was also made an official language in some areas in 2020 by the Chief Minister, Mamata Banerjee.

Religion in West Bengal: A Tapestry of Beliefs

West Bengal is a religiously diverse state with Hinduism being the most widely practiced religion. The 2011 Census reveals that 70.54% of the population follows Hinduism, while 27.01% adhere to Islam. Other minority religions include Christianity (0.72%), Buddhism (0.31%), and Jainism (0.07%). The state also has small communities of Sikhs, Jews, and Zoroastrians, especially concentrated in urban centers like Kolkata.

Key religious features in West Bengal include:

- Hinduism remains central to the state’s culture, with significant festivals such as Durga Puja drawing millions of participants every year.

- Islam is the second-largest religion, and West Bengal is home to a substantial Muslim population, especially in Murshidabad, Malda, and Uttar Dinajpur, which are Muslim-majority districts.

- Buddhism has historical significance in the Darjeeling Hills, where it is still practiced by a significant portion of the population.

- Christianity is most common among the tea garden communities in the Dooars region, primarily in Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar districts.

Cultural Heritage: The Heartbeat of Bengal

West Bengal is synonymous with rich cultural traditions, particularly in literature, music, and the arts. Bengali literature, which has evolved over centuries, is highly respected, both in India and worldwide. The state boasts a lineage of great writers, poets, and thinkers, with key figures like:

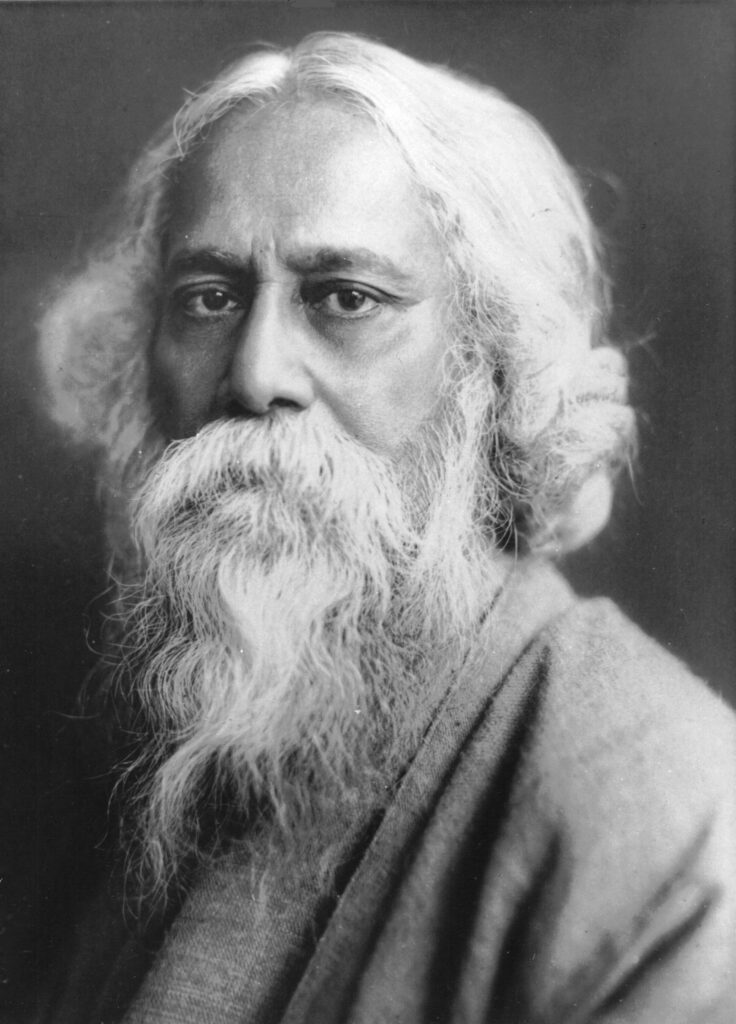

- Rabindranath Tagore, the first Asian to win the Nobel Prize for Literature and the composer of India’s national anthem, Jana Gana Mana. His influence on Bengali literature is immeasurable, and his works cover a wide range of themes, from nationalism to humanity.

- Swami Vivekananda, a key figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga to the Western world, who significantly impacted global perceptions of Hinduism.

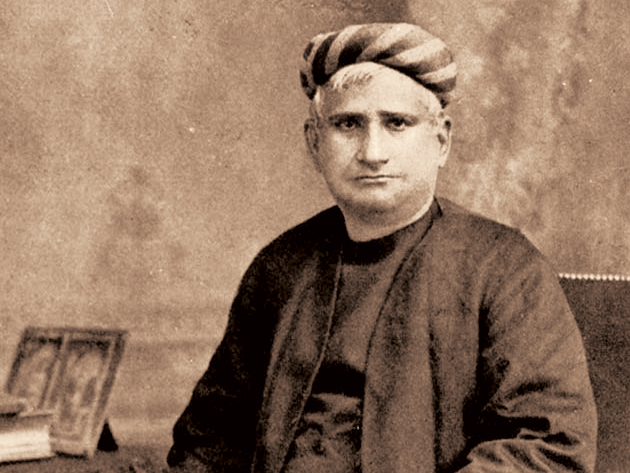

- Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, the author of India’s first novel in Bengali, Anandamath, and the composer of Vande Mataram, a national song of India.

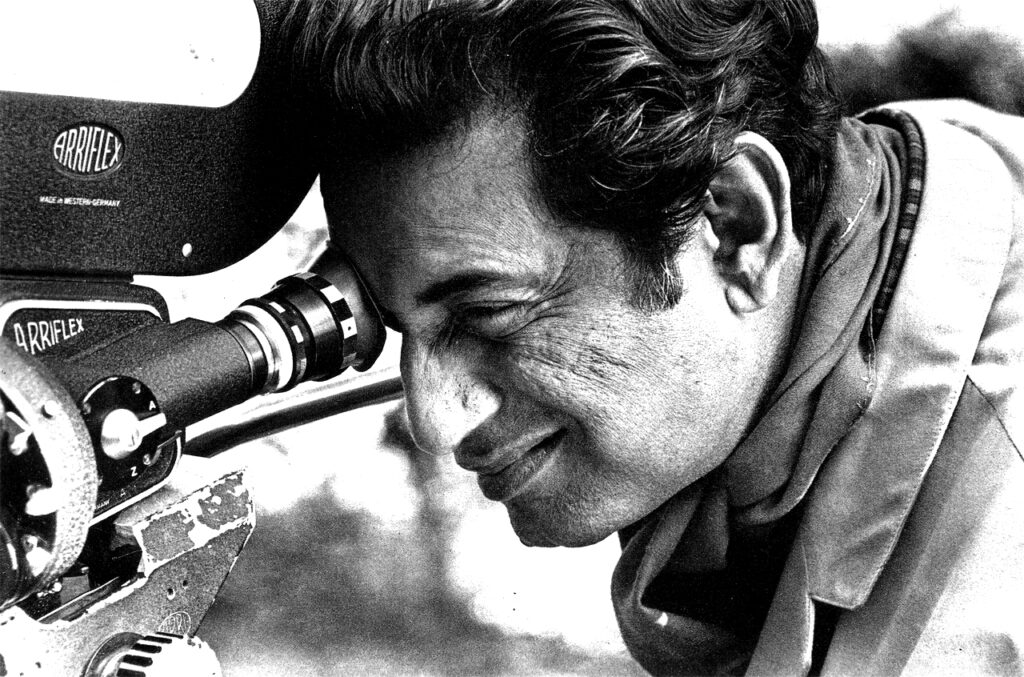

In addition to these literary giants, Bengali theatre and cinema have seen groundbreaking contributions. Pioneers like Satyajit Ray, an acclaimed filmmaker, and Madhusree in theatre have contributed to Bengal’s standing as an influential center for performing arts.

Bengali music also boasts classical and folk traditions, with notable forms such as Nazrul Geeti, associated with poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, and the rhythmic Bengali Baul songs, celebrated for their mysticism and simplicity.

Modern Bengali Literature: A Continuation of Excellence

While Rabindranath Tagore remains the preeminent figure in Bengali literature, the literary scene continues to thrive with many modern authors making significant contributions:

- Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, known for his novels that explore social issues and the life of the underprivileged.

- Manik Bandyopadhyay, a prominent modernist novelist, was particularly noted for his portrayal of the struggles of the working class in Bengal.

- Jibanananda Das, widely recognized as the leading poet of post-Tagore Bengali poetry, is known for his modernist and surrealist works.

The culture of West Bengal is vibrant, dynamic, and ever evolving, with an unbroken tradition of artistic expression, intellectual pursuit, and spiritual exploration. The state’s cultural fabric continues to reflect its historical legacy, while embracing modern influences, making it a key cultural center in India.

Music and Dance: The Rhythmic Soul of West Bengal

West Bengal’s music and dance traditions are as diverse and vibrant as its culture. The state is home to a rich blend of folk, classical, and modern music, as well as an array of distinct dance forms that reflect its social, cultural, and religious fabric.

- Folk Music Traditions: A prominent tradition of Baul music is practiced by the Bauls, a mystic sect known for their soulful songs about divine love and devotion. The Bauls use simple instruments, particularly the ektara, a one-stringed instrument, to accompany their music. Other notable folk music forms in West Bengal include Gombhira and Bhawaiya, each with their unique rhythms and regional appeal. Shyama Sangeet, devotional songs dedicated to goddess Kali, and Kirtan, group devotional songs centered on Lord Krishna, hold significant spiritual importance in the state.

- Rabindrasangeet and Nazrul Geeti: Two of the most celebrated genres of Bengali music are Rabindrasangeet, composed by Rabindranath Tagore, and Nazrul Geeti, penned by Kazi Nazrul Islam. Both composers are central to Bengal’s musical legacy, having shaped the cultural landscape with their compositions. Rabindrasangeet encompasses a wide variety of musical styles and themes, ranging from devotion to humanism. Nazrul Geeti, on the other hand, reflects the revolutionary zeal of Kazi Nazrul Islam, known for his advocacy of social justice and resistance against oppression.

- Modern Music and Emerging Genres: In more recent decades, West Bengal has seen the emergence of Bengali Jeebonmukhi Gaan, a genre rooted in realism. This modern genre reflects the social and political struggles of the common people, offering a unique blend of music and narrative. Additionally, adhunik (modern) Bengali music, often linked to Bengali cinema, has gained widespread popularity.

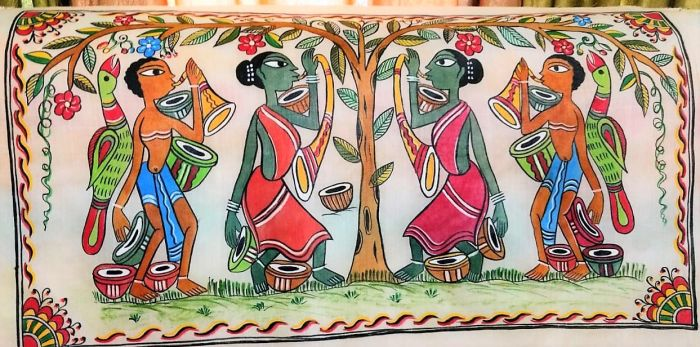

- Dance Forms: The dance traditions of Bengal also draw from its rich folk and religious practices. Chhau dance, originating from Purulia, is a masked dance that combines martial arts and theatrical dance. Known for its vigorous movements and expressive gestures, Chhau dance is recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. Other folk dances, influenced by the tribal traditions of Bengal, continue to be performed during various festivals and celebrations.

Films: The Legacy of Bengali Cinema

Bengali cinema, often referred to as Tollywood (from the Tollygunge neighborhood in Kolkata), is renowned for its artistic and socially relevant films. Over the years, Tollywood has produced a blend of art films and mainstream cinema, contributing significantly to Indian and global film culture.

- Pioneers of Bengali Cinema: Bengali cinema has been shaped by legendary directors like Satyajit Ray, regarded as one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century. Ray’s films, such as Pather Panchali (1955), introduced Indian cinema to the world stage. Along with Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak, Ray helped define the artistic landscape of Bengali films, often tackling social realism, existential dilemmas, and the complexities of human nature.

- Prominent Directors and Actors: The legacy of Bengali cinema continues with directors like Aparna Sen, Rituparno Ghosh, and Kaushik Ganguly, who continue to push the boundaries of film narrative and subject matter. Uttam Kumar, often considered the “hero” of Bengali cinema, had a long-standing romantic pairing with actress Suchitra Sen, creating an iconic onscreen duo. Prosenjit Chatterjee and Soumitra Chatterjee (a frequent collaborator with Satyajit Ray) are other major names in the Bengali film industry.

- Awards and Recognition: Bengali films have consistently received national recognition, winning the National Film Award for Best Feature Film 22 times as of 2020, the highest among all Indian languages. The state’s cinema continues to be an influential force in Indian film culture, blending traditional art forms with contemporary narratives.

Fine Arts: Bengal’s Artistic Heritage

Bengal has a rich tradition of fine arts, spanning from ancient terracotta art to modern abstract painting. The state is particularly known for its contributions to modern art and the Bengal School of Art.

- Terracotta Art and Kalighat Paintings: Bengal’s terracotta art, especially in Hindu temples, is a notable historical legacy. The Panchchura Temple in Bishnupur is an example of the region’s exquisite terracotta art. Another influential artistic tradition is the Kalighat paintings, originating from the Kalighat temple in Kolkata. These vibrant works often depict scenes from mythology, religious rituals, and social life.

- The Bengal School of Art: Founded by Abanindranath Tagore, the Bengal School of Art was a response to Western academic realism, promoting traditional Indian techniques and styles. Abanindranath, along with other prominent artists like Gaganendranath Tagore, Jamini Roy, and Ramkinkar Baij, introduced a new vision for Indian art that blended indigenous traditions with modern artistic expression.

- Modern Art Movements: After Indian Independence, Bengal continued to lead the Indian art world through groups like the Calcutta Group and the Society of Contemporary Artists, which influenced the direction of Indian modernism. Notable artists from this period include Somenath Hore, Biren De, and Rama Rao, whose works explored themes of social realism and abstract art.

Reformist Heritage: Bengal’s Role in Social Change

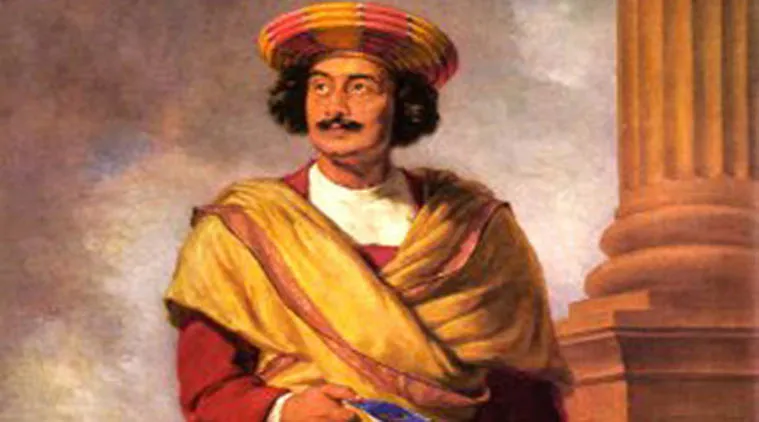

Bengal has long been a cradle of social reform and intellectual thought. Key figures like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar, and Swami Vivekananda championed progressive causes, such as the abolition of sati (the practice of widow immolation) and dowry.

- Raja Ram Mohan Roy played a pivotal role in the Bengal Renaissance, advocating for women’s rights, education, and the abolition of social evils.

- Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar was instrumental in promoting widow remarriage and education for women in colonial Bengal.

- Swami Vivekananda, a spiritual leader, took his message of universal brotherhood and self-realization to the world, making Bengal a key hub for spiritual and intellectual discussions.

This reformist heritage helped lay the foundation for a society more open to change, with Bengal continuing to play a central role in shaping modern Indian culture and society.

Cuisine

Bengali cuisine is characterized by a love for fish, rice, and sweets, with dishes crafted from a wide variety of local ingredients and spices. Fish, particularly hilsa, holds a central place in Bengali cooking, with countless preparations catering to different tastes. Rice-based dishes such as panta bhat (fermented rice) are traditional favorites, often paired with onions and green chilies.

Bengali cooking also includes a wide array of spices such as cumin, mustard, ginger, turmeric, and bay leaves, which infuse the dishes with bold flavors. Sweets are an essential part of the Bengali diet, especially during social occasions and festivals. Rosogolla, chomchom, and sondesh are just a few examples of milk-based sweets that have earned global recognition. The winter months bring special sweet delicacies such as pitha, a sweet cake often stuffed with coconut or jaggery.

Clothing

The traditional attire of Bengali women is the sari, with distinct styles such as Jamdani and Tant saris being popular. These handwoven saris are crafted by artisan communities across the state, with each district specializing in its own weaving technique. Men also wear traditional clothing such as panjabi and dhuti, though western attire is widely accepted in urban areas. The state is famous for its high-quality silk and cotton saris, making handloom weaving an important part of Bengal’s economy.

Festivals

Bengal is known for its grand festivals, the most prominent of which is Durga Puja. This five-day Hindu festival, dedicated to the goddess Durga, involves elaborate decorations, processions, and the creation of beautiful pandals where idols are worshipped. The city of Kolkata transforms into a vibrant spectacle, with thousands of pandals adorned in creative themes. Durga Puja has become more of a cultural celebration, attracting people from different religious backgrounds to join the festivities.

Other major festivals include Rath Yatra, the procession of Lord Jagannath’s chariot, celebrated with much fanfare in Kolkata and rural Bengal, and Poila Baishakh, the Bengali New Year, which is marked by traditional rituals, music, and feasts. Kali Puja, Saraswati Puja, Deepavali, and Lakshmi Puja are also widely celebrated across the state.

Bengali Muslims celebrate Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, marked by prayers, feasts, and social gatherings, while Christmas is celebrated in a unique Bengali way, with celebrations extending across communities. Buddha Purnima is significant in the Darjeeling region, where Buddhist communities gather in processions, chanting mantras and offering prayers.

The Poush Mela at Shantiniketan, known for its folk music, Baul songs, and dance, and the Ganga Sagar Mela, a pilgrimage to the confluence of the Ganges and the sea, highlight the region’s deep spiritual traditions. Whether through food, clothing, or festivals, West Bengal offers a rich and diverse cultural experience that reflects its heritage and the spirit of its people.

Education in West Bengal

West Bengal is home to a rich educational history and an impressive range of institutions, ranging from schools to universities and research institutes. The state has played a pioneering role in the development of the modern education system in India, especially during the British Raj. Notable figures such as Ram Mohan Roy, David Hare, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, William Carey, and Alexander Duff significantly contributed to the establishment of modern schools and colleges in the region.

West Bengal’s educational system is made up of state-run and private schools, including those managed by religious institutions. Instruction is generally conducted in Bengali or English, with some institutions also offering Urdu as a medium of instruction, especially in Central Kolkata. The state’s secondary schools are affiliated with multiple boards, including the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), and the West Bengal Board of Secondary Education.

School Attendance and Literacy

As of 2016, about 85% of children between the ages of 6 and 17 attend school, with a slight difference between urban (86%) and rural (84%) areas. School attendance is nearly universal for children in the 6-14 age group, but drops to 70% for those in the 15-17 age group. Notably, gender disparities exist in the state’s educational system, with more girls attending school compared to boys in the 6-14 age group.

Regarding literacy, 71% of women and 81% of men between 15–49 years are literate. However, only 14% of women in this age group have completed 12 years or more of schooling, compared to 22% of men. Additionally, 22% of women and 14% of men have never attended school.

Notable Schools

Some of the prestigious schools in Kolkata include Ramakrishna Mission Narendrapur, Hindu School, South Point School, La Martiniere Calcutta, and St. Xavier’s Collegiate School. These institutions, many of which were established during the colonial era, offer a blend of neo-classical architecture and a modern curriculum. In Darjeeling, notable schools include St. Paul’s, St. Joseph’s North Point, and Goethals Memorial School.

Higher Education in West Bengal

West Bengal boasts a significant number of universities, with Kolkata being a central hub for higher education in India. The University of Calcutta, established in 1857, is the oldest public university in India and one of the most prestigious. It has 136 affiliated colleges, and the university has played a pivotal role in shaping modern education in the country. Other prominent universities include Jadavpur University, Visva-Bharati University at Santiniketan, and Presidency University, which was granted university status in 2010.

In addition, the state is home to several elite technical institutions like the Indian Institute of Management Calcutta (IIMC), the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur (IITK), and the Indian Institute of Information Technology, Kalyani. These institutes are recognized for their contribution to engineering, management, and research.

Research Institutes

West Bengal is also a hub for scientific research. The Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science in Kolkata is the first research institute in Asia, where Nobel laureate C.V. Raman conducted his famous work on the Raman Effect. Other prominent research institutes in the state include the Bose Institute, Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, and Indian Institute of Chemical Biology.

Notable Scholars

Several notable scholars have either been born or worked in West Bengal, contributing to the fields of physics, chemistry, economics, and education. Some of these scholars include Satyendra Nath Bose, Meghnad Saha, Jagadish Chandra Bose, Prafulla Chandra Roy, and Amartya Sen. The state has also produced Nobel laureates such as Rabindranath Tagore, C.V. Raman, and Abhijit Banerjee.

Media in West Bengal

West Bengal has a rich and diverse media landscape, with a wide variety of newspapers, television channels, and radio stations. As of 2005, there were 505 published newspapers in the state, with 389 of them in Bengali. Among the most prominent Bengali newspapers is Ananda Bazar Patrika, published in Kolkata, which boasts a circulation of 1,277,801 daily copies. This makes it the largest circulation for a single-edition, regional language newspaper in India. Other notable Bengali newspapers include Bartaman, Ei Samay, Sangbad Pratidin, Aajkaal, and Uttarbanga Sambad.

English Newspapers

West Bengal also has a variety of English-language newspapers, which have widespread circulation. These include The Telegraph, The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu, The Statesman, The Indian Express, and Asian Age. Additionally, financial dailies like The Economic Times, Financial Express, Business Line, and Business Standard are widely circulated in the state.

Vernacular Newspapers

Alongside Bengali, there are newspapers published in other vernacular languages, such as Hindi, Nepali, Gujarati, Odia, Urdu, and Punjabi, catering to the diverse linguistic communities in the region.

Television Broadcasting

In the realm of television, DD Bangla is the state-owned broadcaster. Multiple system operators provide a mix of Bengali, Nepali, Hindi, English, and international channels via cable. Bengali television has a robust presence with 24-hour news channels like ABP Ananda, News18 Bangla, Republic Bangla, Kolkata TV, News Time, Zee 24 Ghanta, TV9 Bangla, Calcutta News, and Channel 10.

Radio Broadcasting

All India Radio is the public radio station that serves the state. Additionally, private FM radio stations are available in major cities like Kolkata, Siliguri, and Asansol.

Telecommunication and Internet

The state has widespread cellular phone coverage, with major providers like Vodafone Idea, Airtel, BSNL, and Jio operating in West Bengal. Broadband Internet is available in select towns and cities, offered by the state-run BSNL and other private service providers. Dial-up access is also available throughout the state via BSNL and other companies.

Sports in West Bengal

West Bengal has a vibrant sports culture, with cricket and association football (soccer) being the most popular sports in the state. Unlike many other states in India, West Bengal is known for its deep passion and significant patronage of football. Kolkata, the capital of the state, is considered one of the major football hubs in India. It is home to some of the country’s top national football clubs, including Mohun Bagan Super Giant, East Bengal Club, and Mohammedan Sporting Club, all of which have a storied history and loyal fanbases.

Stadiums and Sporting Venues

West Bengal boasts several large and historically significant sports stadiums, with Eden Gardens in Kolkata being the most iconic. Once home to over 100,000 spectators, Eden Gardens was one of only two stadiums worldwide with such a vast seating capacity. However, following renovations before the 2011 Cricket World Cup, the capacity was reduced to 66,000. Despite this, it remains one of the most renowned cricket stadiums globally. Eden Gardens serves as the home ground for teams like the Kolkata Knight Riders, the Bengal cricket team, and the East Zone cricket team. The stadium also hosted the 1987 Cricket World Cup final, which remains a historic event in Indian cricket.

Another major stadium in the state is the Vivekananda Yuba Bharati Krirangan (VYBK), also known as the Salt Lake Stadium. This multipurpose stadium holds the distinction of being the largest stadium in India by seating capacity, with 85,000 seats. Prior to its renovation in 2011, the stadium held a 120,000 capacity, making it the second-largest football stadium in the world at that time.

Over the years, VYBK has hosted numerous national and international sporting events, such as the SAF Games in 1987 and the 2011 FIFA friendly match between Argentina and Venezuela, which featured Lionel Messi. The stadium was also the venue for the final match of the 2017 FIFA U-17 World Cup and hosted Oliver Kahn’s farewell match in 2008.

Notable Sports Personalities

West Bengal has produced several notable sports figures, especially in cricket and tennis. Sourav Ganguly, a former captain of the Indian national cricket team, is one of the most famous names in Indian cricket, hailing from Kolkata. Other notable cricketers from the state include Pankaj Roy. In tennis, Leander Paes, an Olympic bronze medalist, has made a mark internationally. In the realm of chess, Dibyendu Barua, a celebrated chess grandmaster, is another significant figure from West Bengal.

West Bengal’s passion for sports, combined with its rich infrastructure and history, continues to foster a strong sporting culture, making it a key contributor to India’s sporting landscape.