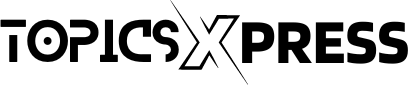

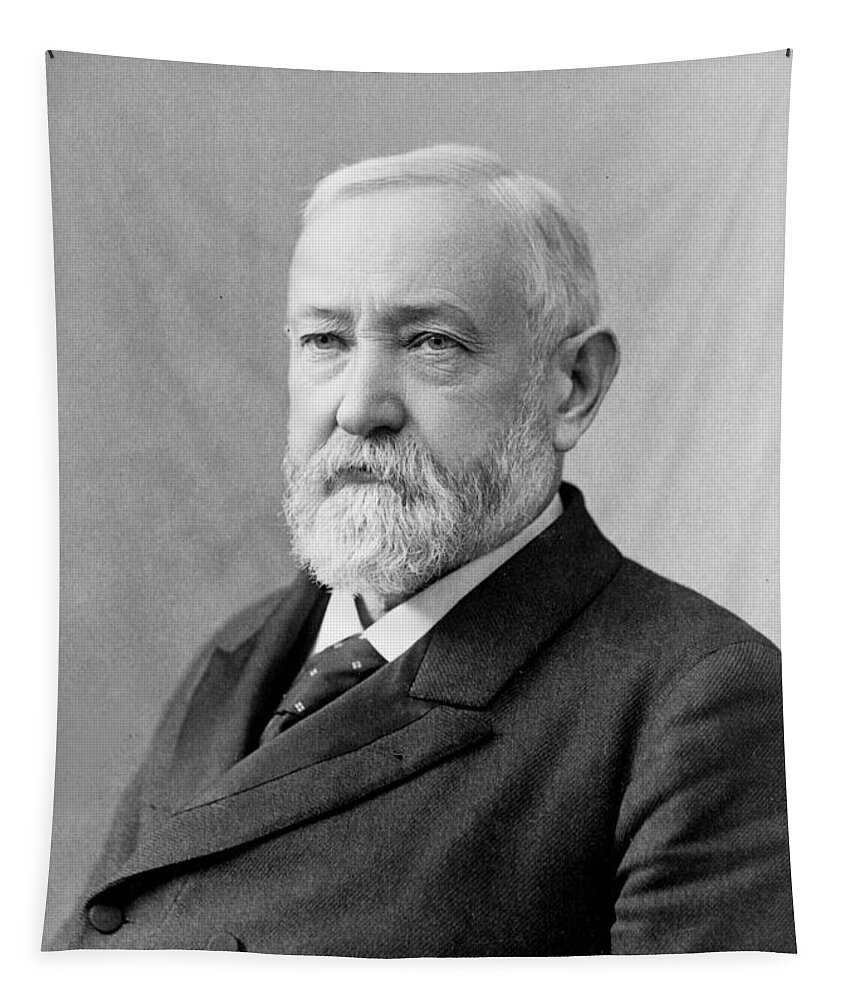

Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President of the United States, presided over the nation from March 4, 1889, to March 4, 1893. As a prominent member of the Republican Party, he achieved a notable political milestone by defeating incumbent President Grover Cleveland in the 1888 election. This victory marked the first time in U.S. history that a sitting president was unseated in a bid for re-election. Benjamin Harrison administration was defined by significant legislative accomplishments, ambitious foreign policy initiatives, and a transformative vision for addressing the challenges of the late 19th century.

Benjamin Harrison early life and political career laid the foundation for his presidency. Born on August 20, 1833, in North Bend, Ohio, he was part of a family with deep political roots; his grandfather, William Henry Harrison, served as the ninth president. After completing his education at Miami University, Benjamin Harrison embarked on a legal career in Indianapolis, Indiana, where he became active in local politics. His strong Republican values and opposition to slavery positioned him as a significant figure in the party during a tumultuous era.

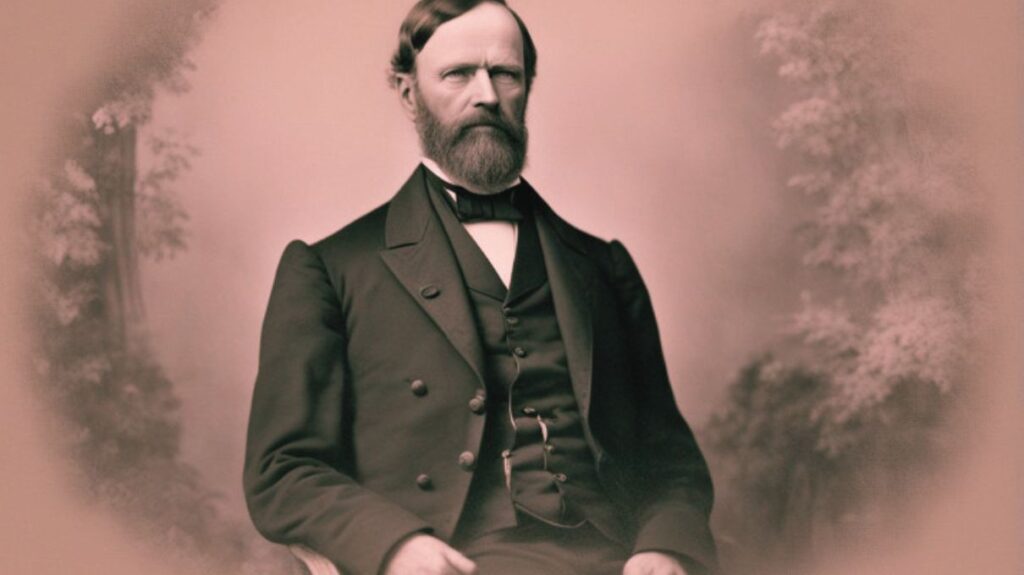

Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President (topicsxpress.com)

Throughout the 1880s, Benjamin Harrison garnered attention for his leadership skills and his commitment to Republican ideals, ultimately earning a spot in the U.S. Senate. His tenure there was marked by his dedication to issues such as economic reform and veterans’ affairs. Harrison’s ability to connect with voters and articulate a clear vision for the country played a crucial role in his successful presidential campaign. His platform focused on economic growth, tariff reform, and the promotion of American industry, appealing to a populace eager for progress and stability.

Benjamin Harrison presidency emerged during a time of rapid industrialization in the United States. The nation was transitioning from an agrarian society to an industrial powerhouse, leading to significant economic changes and social challenges. Benjamin Harrison recognized the need for government intervention to support emerging industries and protect consumers, laying the groundwork for his administration’s legislative agenda. His leadership style, characterized by a strong commitment to party unity and reform, aimed to address the complex issues facing the nation.

In conclusion, Benjamin Harrison’s presidency was a pivotal chapter in American history. His electoral victory over Cleveland set the stage for a dynamic administration focused on significant reforms and expansion of U.S. influence both domestically and abroad. As we delve deeper into his time in office, it becomes clear that Benjamin Harrison efforts were instrumental in shaping the policies that defined the late 19th century, influencing the trajectory of the nation for years to come.

Family and Education of Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison was born on August 20, 1833, in North Bend, Ohio, to Elizabeth Ramsey (Irwin) and John Scott Harrison, making him the second of ten children. He came from a distinguished lineage; his grandfather was President William Henry Harrison, and his great-grandfather, Benjamin Harrison V, signed the Declaration of Independence and served as governor of Virginia. Despite this notable ancestry, Harrison’s family was not wealthy, and his father, a two-term U.S. congressman, prioritized spending on his children’s education.

Benjamin Harrison early schooling took place in a log cabin, but his parents later arranged for a tutor to prepare him for college. In 1847, he and his older brother enrolled at Farmer’s College near Cincinnati, where he met Caroline “Carrie” Lavinia Scott, who would become his wife. After two years, he transferred to Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, graduating in 1852. During his time at Miami, he joined the Phi Delta Theta fraternity and the Delta Chi law fraternity, forming connections that would last throughout his life. His education was influenced by Professor Robert Hamilton Bishop, and he became a lifelong Presbyterian, joining the church while in college.

Marriage and Early Career of Benjamin Harrison

After graduating from college in 1852, Benjamin Harrison began studying law under Judge Bellamy Storer in Cincinnati. Before completing his studies, he married Caroline Scott on October 20, 1853, in a ceremony officiated by her father, a Presbyterian minister. The couple had two children: Russell Benjamin Harrison and Mary “Mamie” Scott Harrison.

Following their marriage, the Benjamin Harrison moved to The Point, his father’s farm in southwestern Ohio, where he completed his legal studies. He was admitted to the Ohio bar in early 1854 and sold inherited property for $800 (about $27,129 in 2023) to relocate with Caroline to Indianapolis, Indiana. There, he began practicing law in the office of John H. Ray and worked as a crier for the federal court, earning $2.50 a day. He also served as a Commissioner for the U.S. Court of Claims and played an active role in local organizations, becoming a founding member and the first president of the University Club and the Phi Delta Theta Alumni Club. Both Benjamin Harrison and his wife took leadership roles at Indianapolis’s First Presbyterian Church.

Initially raised in a Whig household, Benjamin Harrison joined the newly formed Republican Party in 1856, campaigning for presidential candidate John C. Frémont. In 1857, he was elected Indianapolis city attorney, earning an annual salary of $400 (around $13,080 in 2023). Harrison formed a law partnership with William Wallace in 1858, establishing the firm Wallace and Benjamin Harrison. He was elected reporter of the Indiana Supreme Court in 1860 and served as secretary of the Republican State Committee. After Wallace’s election as county clerk, Harrison partnered with William Fishback to form Fishback and Benjamin Harrison, continuing until he enlisted in the Union Army following the outbreak of the Civil War.

Election of 1888

The 1888 presidential election marked a significant turning point in American political history. Initially, James G. Blaine, the Republican nominee from the previous election in 1884, was the frontrunner for the party’s nomination. However, Blaine’s reluctance to pursue another campaign led to a fragmentation among his supporters, pushing them to consider other candidates. Among those contenders, John Sherman of Ohio emerged as a prominent figure. Other notable candidates included Chauncey Depew from New York, Russell Alger of Michigan, and Walter Q. Gresham, a respected federal appellate judge.

Despite his substantial political background, Blaine did not openly endorse a successor, but in a private correspondence dated March 1, 1888, he expressed his belief that Benjamin Harrison was the best choice to carry the Republican banner. Harrison, who had served as the United States Senator from Indiana from 1881 to 1887, announced his candidacy in February 1888, presenting himself as a rejuvenated Republican.

During the Republican National Convention, Benjamin Harrison initially struggled, ranking fifth on the first ballot, with Sherman in the lead. However, as Blaine’s supporters began to realign their preferences, Harrison’s appeal grew, as he attracted a coalition of various factions within the party. His nomination came on the eighth ballot, with a decisive vote count of 544 to 108. Harrison selected Levi P. Morton from New York as his running mate.

In the general election, Benjamin Harrison faced off against incumbent President Grover Cleveland, who had been in office since 1885. Harrison adopted a traditional front-porch campaign strategy, contrasting sharply with Blaine’s previous, more active approach. He received delegations of supporters in Indianapolis and made numerous statements from his home, while Cleveland opted for a more limited public engagement.

The campaign focused heavily on the issue of protective tariffs, appealing to industrial voters in key states like New York, New Jersey, and Indiana. Voter turnout surged to an impressive 79.3%, with nearly eleven million ballots cast. Despite Benjamin Harrison receiving about 90,000 fewer popular votes than Cleveland, he triumphed in the electoral college with a tally of 233 to 168. This election was notable as it was one of three instances in U.S. history where a candidate won the presidency without winning the popular vote.

After the election, Benjamin Harrison supporters acknowledged that he owed his narrow victory to a complex web of political promises made on his behalf. Pennsylvania’s Boss Matthew Quay remarked on Harrison’s belief that divine intervention played a role in his victory, hinting at the political machinations behind the scenes. The concurrent congressional elections resulted in the Republicans gaining nineteen seats in the House of Representatives, enabling them to reclaim control of Congress for the first time since the 1874 elections. This significant shift laid the groundwork for Harrison’s ambitious legislative agenda during his presidency.

Inauguration of Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison was inaugurated as the 23rd President of the United States on March 4, 1889. Chief Justice Melville Fuller administered the oath of office during a rainy ceremony in Washington D.C. Outgoing President Grover Cleveland, who Harrison had defeated in the 1888 election, attended the event and even held an umbrella for Harrison to protect him from the downpour. At 5 feet 6 inches tall, Benjamin Harrison was not only one of the shorter U.S. presidents but also the last to wear a full beard. Despite the unpleasant weather, the event marked a significant moment in U.S. history, with Harrison following in the footsteps of his grandfather, William Henry Harrison, who had served as president decades earlier. Notably, Benjamin Harrison’s inaugural speech was brief, especially when compared to his grandfather’s, who still holds the record for the longest inaugural address in U.S. history.

In his address, Benjamin Harrison emphasized the importance of education and religion in the nation’s development. He also highlighted the need for economic growth in southern states and western territories, urging them to achieve the industrial success seen in the eastern United States. A major point of his speech was his advocacy for a protective tariff, aimed at safeguarding American industries. He spoke on corporate responsibility, stating that if major corporations adhered more closely to legal regulations, they would face fewer issues with the government. Additionally, Harrison called for reforms such as the regulation of trusts, safety standards for railroad workers, and greater federal support for education.

His speech also touched on the need for infrastructure improvements, statehood for U.S. territories, and pension benefits for military veterans, a cause that earned him widespread support from veterans’ groups. On foreign policy, Benjamin Harrison reiterated the importance of the Monroe Doctrine, which emphasized non-intervention by European powers in the Americas. He also advocated for a stronger, modernized Navy to protect American interests abroad. Harrison’s commitment to international peace was clear, as he expressed a desire for noninterference in the internal affairs of other nations, reflecting a more diplomatic approach to foreign relations.

Benjamin Harrison’s Presidential Cabinet (1889-1893)

Overview of the Benjamin Harrison Cabinet

Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd President of the United States, assembled a cabinet that would guide his administration from 1889 to 1893. While his choices for key government positions reflected the political dynamics of the time, they also had lasting impacts on his political strength and administration. The composition of his cabinet reveals a complex interplay of personalities and policies that would define his presidency.

| Office | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| President | Benjamin Harrison | 1889–1893 |

| Vice President | Levi P. Morton | 1889–1893 |

| Secretary of State | James G. Blaine | 1889–1892 |

| Secretary of State | John W. Foster | 1892–1893 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | William Windom | 1889–1891 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Charles Foster | 1891–1893 |

| Secretary of War | Redfield Proctor | 1889–1891 |

| Secretary of War | Stephen B. Elkins | 1891–1893 |

| Attorney General | William H. H. Miller | 1889–1893 |

| Postmaster General | John Wanamaker | 1889–1893 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Benjamin F. Tracy | 1889–1893 |

| Secretary of the Interior | John Willock Noble | 1889–1893 |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Jeremiah M. Rusk | 1889–1893 |

The Formation of Harrison’s Cabinet

Benjamin Harrison initial cabinet selections caused friction among influential Republican leaders across several states, including New York, Pennsylvania, and Iowa. Many of these party insiders felt alienated, a factor that ultimately undermined Harrison’s future political leverage. His refusal to rely on patronage—the practice of awarding government positions to supporters—stood in stark contrast to the expectations of many party members.

Senator Shelby Cullom famously noted Harrison’s reluctance to use federal positions as rewards, recalling how even favors done for senators were carried out in a manner that often offended rather than pleased. This stance may have contributed to his inability to secure stronger political alliances during his tenure.

James G. Blaine and Foreign Policy Leadership

At the center of the administration’s foreign policy was Secretary of State James G. Blaine, a prominent political figure with a history of influence. Benjamin Harrison initially delayed appointing Blaine to the position, largely because he feared a repeat of the situation under President James Garfield, where Blaine had wielded considerable control over the administration’s personnel choices. However, despite this initial tension, Blaine became a key member of the administration and played a significant role in shaping U.S. foreign relations during Harrison’s presidency.

Even though Blaine’s health declined, and he resigned in 1892, his earlier tenure helped guide critical decisions, such as trade policy and diplomatic negotiations. Blaine’s replacement, John W. Foster, continued the administration’s foreign policy with a focus on expanding U.S. influence abroad.

Treasury and Other Key Appointments

For the crucial position of Secretary of the Treasury, Benjamin Harrison passed over two dominant New York Republicans, Thomas C. Platt and Warner Miller, both of whom were battling for control of their state’s Republican Party. Instead, Harrison appointed William Windom, a former senator from Minnesota who had also served as Secretary of the Treasury under President Garfield. After Windom’s death in 1891, Charles Foster, a former governor of Ohio, was selected to continue overseeing the nation’s finances.

New York’s representation in the cabinet was also maintained through Benjamin F. Tracy, who took on the role of Secretary of the Navy. Another critical appointment was Pennsylvania’s John Wanamaker as Postmaster General, though many Pennsylvania Republicans had hoped for a more prestigious position within the cabinet.

The Department of Agriculture, recently upgraded to a cabinet-level position by Benjamin Harrison predecessor, President Grover Cleveland, was headed by Wisconsin Governor Jeremiah M. Rusk. Rusk’s leadership helped to formalize policies that would support the nation’s growing agricultural sector.

Notable Cabinet Members and Their Roles

Benjamin Harrison administration featured several other noteworthy figures. John Willock Noble, a lawyer with a reputation for honesty and integrity, became Secretary of the Interior. Noble faced the challenge of restoring credibility to a department plagued by corruption scandals in previous administrations.

Redfield Proctor, a Vermont native who played a key role in securing Benjamin Harrison nomination, served as Secretary of War. When Proctor resigned in 1891 to take a seat in the Senate, he was replaced by Stephen B. Elkins, who continued to oversee the nation’s military affairs.

Finally, Attorney General William H. H. Miller, a close personal friend of Benjamin Harrison, was appointed to handle legal affairs. Harrison’s relationship with Miller was a reflection of his broader practice of relying on trusted friends and confidants for key positions within his administration.

Weekly Meetings and Policy Formation

Benjamin Harrison approach to governance involved a structured routine of cabinet meetings, with full sessions occurring twice weekly. Additionally, he maintained individual weekly meetings with each cabinet member, ensuring a regular flow of information and policy discussions. While Harrison often made the final decisions on key issues, his cabinet members played pivotal roles in advising and shaping the administration’s domestic and international policies

Judicial Appointments During Benjamin Harrison’s Presidency

Benjamin Harrison, during his tenure as the 23rd President of the United States, made significant contributions to the federal judiciary. His appointments, particularly to the U.S. Supreme Court, left a lasting imprint on the judicial landscape of the nation. In addition to Supreme Court nominations, Harrison also played a key role in shaping the structure of the federal court system through legislative reform.

Supreme Court Appointments

During his presidency, Benjamin Harrison appointed four justices to the Supreme Court, a considerable number that would influence the Court’s direction well into the 20th century. The first of these appointments was David Josiah Brewer, a respected judge from the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. Brewer, who was also the nephew of then-Associate Justice Stephen Field, had previously been considered for a cabinet role. His nomination was swiftly confirmed, adding a conservative voice to the Supreme Court.

Soon after Brewer’s appointment, the Court faced another vacancy with the death of Justice Stanley Matthews. Benjamin Harrison, after considering various candidates, selected Henry Billings Brown, a Michigan judge known for his expertise in admiralty law. Brown’s experience in legal matters related to maritime issues made him a fitting choice, and his nomination was similarly approved.

In 1892, a third vacancy arose, and Benjamin Harrison nominated George Shiras to fill the position. At the age of 60, Shiras’s nomination was controversial, as he was older than the typical age for new justices. Nonetheless, his qualifications outweighed concerns about his age, and he secured Senate approval.

The final Supreme Court nomination during Benjamin Harrison presidency was Howell Edmunds Jackson in 1893. Jackson’s nomination followed the death of Justice Lucius Lamar. At the time, Harrison knew that the incoming Senate would be dominated by Democrats, so he chose Jackson, a well-respected Democrat from Tennessee with whom he shared a friendly rapport. By selecting a nominee from the opposition party, Harrison ensured that his final judicial appointment would not be rejected. Jackson’s nomination was successful, although his tenure was brief due to his untimely death just two years later.

Of the four justices appointed by Benjamin Harrison, David Josiah Brewer served the longest, remaining on the bench until his death in 1910. The other appointees also had lasting influence, with each playing a key role in shaping decisions during their respective tenures.

Judiciary Act of 1891 and Structural Reforms

Benjamin Harrison impact on the judiciary extended beyond individual appointments. His administration oversaw the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1891, a landmark piece of legislation that transformed the federal court system. This act abolished the old circuit courts and established the United States Courts of Appeal, creating a permanent intermediate appellate court structure.

Before this reform, Supreme Court justices were required to “ride circuit,” meaning they had to travel and preside over cases in lower courts throughout the country. The creation of the Courts of Appeal eliminated this burdensome practice, significantly reducing the workload of the Supreme Court and allowing justices to focus solely on cases of national importance.

The Judiciary Act also provided for the appointment of new judges to the newly established Courts of Appeal, and Benjamin Harrison took full advantage of this opportunity. He appointed ten judges to the Courts of Appeal, two judges to the circuit courts, and 26 judges to the district courts. Since the circuit courts were abolished during his presidency, Harrison became one of only two presidents, along with Grover Cleveland, to appoint judges to both the circuit courts and the Courts of Appeal.

Benjamin Harrison Legacy in the Judiciary

Benjamin Harrison judicial appointments and structural reforms left a lasting legacy on the federal judiciary. By ensuring that the Courts of Appeal were established as permanent fixtures in the U.S. judicial system, Harrison played a pivotal role in modernizing the court system, making it more efficient and better equipped to handle the growing number of cases. His Supreme Court appointments also shaped the interpretation of U.S. law for years to come, with justices like Brewer remaining on the bench for decades after his presidency.

Through both his appointments and the Judiciary Act of 1891, Benjamin Harrison’s contributions to the federal judiciary continue to influence the system today. His foresight in court reform and careful selection of judicial nominees demonstrate his deep commitment to improving the efficiency and fairness of the American legal system.

States Admitted to the Union During Benjamin Harrison’s Presidency

Benjamin Harrison’s presidency (1889-1893) holds the unique distinction of overseeing the admission of more new states to the Union than any other administration. When he took office, it had been more than a decade since any new state had joined the Union, primarily due to resistance from Congressional Democrats. Their reluctance stemmed from the belief that newly admitted states would likely send Republican representatives to Congress, tipping the balance of power.

However, once the Republican Party gained control, they saw an opportunity to strengthen their Senate majority. Through a series of legislative efforts during the 50th Congress, particularly in the lame-duck session, they managed to push through bills that led to the admission of several new states. In November 1889, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Washington were all welcomed into the Union. The following year, in July 1890, Idaho and Wyoming also achieved statehood.

This influx of new states had a significant political impact, particularly in the Senate. These six new states collectively sent twelve Republican senators to Washington, bolstering the party’s power during the 51st Congress. The admission of these states not only expanded the geographical boundaries of the United States but also cemented the Republican Party’s influence in the national political landscape.

The rapid admission of these western states played a crucial role in shaping Harrison’s presidency and the future direction of the nation. It solidified the Republicans’ hold on the Senate, giving them the leverage to pass significant legislation and reinforcing the party’s dominance in the years to come.

The Sherman Antitrust Act and Harrison’s Role in Regulating Monopolies

During the presidency of Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893), growing concern over the unchecked power of monopolies and business trusts led to significant legislative action aimed at regulating the economy. Trusts were corporate arrangements where multiple competing companies merged under a single management, which allowed them to dominate markets, eliminate competition, and manipulate prices. By the late 19th century, trusts had taken control of key industries, such as steel, sugar, whiskey, and tobacco, sparking widespread alarm among politicians from both parties.

One of the most influential figures in tackling the issue of monopolies was Senator John Sherman, who worked closely with Benjamin Harrison and played a pivotal role in drafting legislation to regulate trusts. The result was the Sherman Antitrust Act, passed by the 51st United States Congress in 1890. This law represented a groundbreaking attempt by the federal government to control the excesses of big business and restore competitive markets.

The Sherman Antitrust Act specifically declared that any “combination in the form of trust… in restraint of trade or commerce” was illegal. Its main goal was to prevent companies from using monopolistic practices to stifle competition, maintain high prices, and limit choices for consumers. The act was passed with widespread support and was seen as a crucial step toward regulating the growing influence of corporate power over the American economy.

Along with the earlier Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which sought to regulate the railroad industry, the Sherman Antitrust Act was one of the first major federal laws aimed at curbing the power of large corporations. Benjamin Harrison fully supported the law’s intent, viewing it as essential to preventing the harmful effects of monopolies on both small businesses and consumers.

However, despite the passage of the Sherman Act, the Benjamin Harrison administration faced several challenges in enforcing it. The Department of Justice, responsible for handling antitrust cases, was understaffed and lacked the resources to pursue complex legal battles against well-funded corporate interests. Furthermore, the vague language of the Sherman Act, combined with narrow interpretations by federal judges, made it difficult to secure convictions against monopolistic corporations.

Even with these obstacles, Benjamin Harrison administration made some progress. The Department of Justice successfully won a case against a Tennessee coal company for violating antitrust laws and initiated several other lawsuits against powerful trusts. However, the limited enforcement capacity of the government during this period left much of the act’s potential unrealized.

The difficulties in enforcing the Sherman Act and the restrictive rulings from the courts demonstrated the need for stronger regulations in the future. These challenges eventually led to the passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914, which provided more explicit guidelines for regulating monopolies and strengthened the government’s ability to combat corporate abuse.

In conclusion, while the Benjamin Harrison administration laid the groundwork for federal antitrust legislation with the Sherman Antitrust Act, its enforcement efforts were hampered by limited resources and judicial interpretations. Nevertheless, Harrison’s efforts marked an important first step in the long battle to curb monopolistic power in the U.S. economy.

The McKinley Tariff and Benjamin Harrison Economic Policy

Tariffs were a critical issue during Benjamin Harrison’s presidency (1889-1893), accounting for 60% of federal revenue in 1889. In the Gilded Age, tariffs were not just an economic tool but a central point of political debate. Harrison, like many Republicans of his time, saw high tariffs as essential to protecting American industry. He believed that tariffs shielded domestic manufacturing jobs from competition with cheaper, imported goods. High tariffs were at the heart of his economic policy, alongside maintaining a stable currency.

However, the high tariff rates had led to a large surplus in the federal Treasury, which sparked calls for reform. Many Democrats and members of the emerging Populist movement argued for lowering tariffs, claiming the surplus indicated that taxes were too high. These groups advocated for reducing tariffs to ease the financial burden on consumers and increase competition. In contrast, most Republicans, including Harrison, preferred to keep tariffs high, using the surplus for internal improvements and eliminating some internal taxes. The Republican victory in the 1888 election was viewed by the party as a mandate to raise tariffs even further.

Harrison played an active role in the tariff debate, often inviting key members of Congress to dinner in an effort to persuade them to support a new tariff bill. Representative William McKinley and Senator Nelson W. Aldrich spearheaded the McKinley Tariff, which aimed to raise tariff rates even higher. The McKinley Tariff set some rates so high they were essentially prohibitive, discouraging imports and giving American manufacturers a significant advantage in domestic markets.

At the urging of Secretary of State James G. Blaine, Harrison incorporated reciprocity provisions into the tariff bill. These provisions allowed the president to reduce tariffs on goods from countries that agreed to lower their tariffs on American exports. This was a unique feature of the McKinley Tariff, as it gave the president an unusually high degree of power to unilaterally adjust tariff rates in trade negotiations.

One of the notable provisions of the McKinley Tariff was the removal of tariffs on imported raw sugar. To compensate domestic sugar producers, the law included a subsidy of two cents per pound for American sugar growers. This blend of protectionism and subsidies was designed to balance the interests of both domestic producers and consumers.

The McKinley Tariff passed Congress after Republican leaders secured the support of Western senators, partly by passing the Sherman Antitrust Act and making other concessions. Harrison signed the McKinley Tariff into law in October 1890.

The Currency Debate and Benjamin Harrison Middle Ground

One of the most contentious issues of the late 19th century was the debate over currency: should the U.S. adhere to a strict gold standard or allow the coinage of both gold and silver? This debate gained momentum due to worldwide deflation in the late 1800s, which caused incomes to shrink while debts remained unchanged. As a result, debtors, farmers, and the working class began advocating for the free coinage of silver, believing that an expanded currency supply would lead to inflation, thereby reducing the real value of their debts.

At the heart of the debate was the fact that silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold. This led to an imbalance: taxpayers paid their government obligations in silver, while international creditors insisted on payment in gold. This mismatch strained the country’s gold reserves, leading to concerns about the nation’s economic stability.

The issue of silver coinage cut across party lines. Western Republicans and Southern Democrats united in calling for the free coinage of silver, hoping it would provide relief to struggling farmers and debtors. In contrast, representatives from the industrialized Northeast, regardless of party affiliation, were staunch supporters of the gold standard. They feared that an inflationary silver policy would destabilize the economy and harm international trade.

Although the currency issue was not a significant topic during the 1888 presidential campaign, it soon became a defining aspect of Benjamin Harrison’s administration. Harrison tried to strike a balance between the two sides, advocating for a compromise. He supported the idea of silver coinage but insisted that silver should be minted at its true market value, not at a fixed ratio to gold, which he believed would lead to economic instability. Despite his efforts, Congress did not embrace this middle ground approach.

In 1890, the currency debate intensified, leading to the passage of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, named after Senator John Sherman, who played a pivotal role in its creation. The act required the government to purchase 4.5 million ounces of silver each month. Many believed that this law would resolve the currency debate by satisfying both sides—silver advocates saw it as a step toward increased coinage, while gold supporters hoped it would limit silver’s influence on the economy.

Harrison signed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act into law, hoping it would quell the controversy. However, the bill had the unintended consequence of further depleting the nation’s gold reserves, as more silver entered circulation while creditors continued to demand payment in gold. This imbalance persisted throughout Benjamin Harrison presidency and would remain a challenge for his successors.

Civil Service Reform and Pensions in Benjamin Harrison Presidency

Civil service reform was a significant issue during Benjamin Harrison’s presidency (1889-1893). Harrison, who championed a merit-based system, faced political pressure from both sides over government job appointments. Although the Pendleton Act of 1883 had curtailed the spoils system, Harrison’s early months were dominated by appointments that alienated various factions. Despite appointing reform-minded individuals like Theodore Roosevelt to the Civil Service Commission, Harrison took little action to advance reform.

In contrast, Harrison decisively addressed the growing surplus in the federal treasury by increasing pensions for Civil War veterans, a majority of whom were Republicans. He supported the Dependent and Disability Pension Act, which significantly expanded financial aid for disabled veterans. Under his administration, pension expenditures reached $135 million, marking the highest in U.S. history at that time. However, this surge in spending led to allegations of mismanagement within the Pension Bureau, particularly under Commissioner James R. Tanner. Despite concerns, Harrison maintained Tanner’s successor, Green B. Raum, even amid accusations of corruption. Ultimately, Harrison’s legacy intertwines civil service reform efforts and the expansive pension system, contributing to the era’s reputation as the “Billion-Dollar Congress.”

Civil Rights During Harrison’s Presidency

During Benjamin Harrison’s presidency (1889-1893), civil rights for African Americans remained a pressing issue, particularly in the South, where many states violated the Fifteenth Amendment by disenfranchising Black voters. Recognizing the failure of the Republican Party’s “lily-white policy” to attract Southern whites, Harrison endorsed the Federal Elections Bill, which aimed to provide federal oversight of elections for the U.S. House of Representatives. Despite its passage in the House in July 1890, the bill faced delays in the Senate and was ultimately tabled in January 1891. This failure represented the last significant federal effort to protect African American civil rights until the 1930s, allowing Southern states to implement Jim Crow laws.

After the bill’s defeat, Harrison continued advocating for civil rights in Congress. Although Attorney General William H. H. Miller pursued prosecutions for voting rights violations, white juries frequently refused to convict offenders. Harrison also supported Senator Henry W. Blair’s bill to fund racially integrated schools, but it was defeated in the Senate. Additionally, he endorsed a constitutional amendment to counter the Supreme Court’s decision that had weakened the Civil Rights Act of 1875, but no progress was made on this front.

The 1890 Midterm Elections

The 1890 midterm elections marked a significant turning point in U.S. politics, culminating in substantial losses for President Benjamin Harrison and the Republican Party. Despite having enacted one of the most ambitious domestic legislative programs in peacetime, the Republicans suffered a dramatic defeat, losing nearly 100 seats in the House of Representatives. As a result, Democrat Charles Frederick Crisp replaced Thomas Brackett Reed as Speaker of the House, although Republicans managed to maintain their majority in the Senate.

These elections also saw the emergence of the Populist Party, a new political force driven by farmers from the South and Midwest. Stemming from the Farmers’ Alliance and the Knights of Labor, the Populists advocated for policies like bimetallism, the restoration of the Greenback, and nationalization of railroads and telegraphs. Their rising popularity was fueled by widespread discontent over the McKinley Tariff, which many believed favored industrialists over farmers.

As disaffected Republicans gravitated toward the Populist cause, particularly in the Midwest, the Democratic Party gained traction, paving the way for influential figures like William Jennings Bryan. This election underscored growing divisions in American politics and the shifting alliances among parties.

National Forests and Conservation During Harrison’s Presidency

In March 1891, President Benjamin Harrison signed the Land Revision Act, reflecting a bipartisan commitment to reclaim surplus public lands that had previously been allocated for settlement or railroad use. A significant aspect of this legislation was Section 24, added at Harrison’s request by Secretary of the Interior John Noble, which empowered the President to designate forested public lands as national reserves.

Shortly after the act’s passage, Harrison established the first forest reserve adjacent to Yellowstone Park in Wyoming, marking a pivotal moment in U.S. conservation efforts. Over his term, Harrison designated a total of 22 million acres as national forest reserves, highlighting his administration’s dedication to protecting natural resources for future generations.

Additionally, Harrison was the first president to grant federal protection to a prehistoric Indian ruin, Casa Grande in Arizona, demonstrating an early recognition of the importance of preserving cultural heritage sites. These actions laid the groundwork for the future conservation movement and reflected a growing awareness of environmental issues in the late 19th century, which would continue to shape U.S. policy in the years to come.

Native American Policy Under Harrison

During Benjamin Harrison’s presidency, tensions between the U.S. government and Native American tribes, particularly the Lakota Sioux, escalated significantly. The Sioux, influenced by Wovoka and the Ghost Dance movement, sought spiritual renewal amidst their struggles. Misunderstanding the movement as a militant uprising, Harrison ordered federal troops to Pine Ridge in November 1890 to prevent unrest.

This military presence heightened tensions, culminating in the tragic Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890, where at least 146 Sioux, including women and children, were killed by the Seventh Cavalry. Despite the horror of the massacre, Harrison believed the U.S. policy of assimilation through the Dawes Act was effective, viewing it as a means for Native Americans to integrate into white society.

Harrison’s administration further opened Indian Territory to white settlement, exemplified by the 1889 Land Rush, which saw thousands of settlers claim lands previously designated for the Five Civilized Tribes. This policy, along with the Oklahoma Organic Act of 1890, led to the creation of Oklahoma Territory, resulting in significant loss of land and sovereignty for Native American tribes.

Federal Immigration Control and Ellis Island

Under President Benjamin Harrison, significant changes were made to U.S. immigration policy, marking a shift from state to federal oversight. In 1890, Harrison approved the federal assumption of immigration control, which ended the previous practice of state regulation. This transition culminated in the Immigration Act of March 3, 1891, which Harrison signed into law.

This act established a federal immigration agency within the Treasury Department and set regulations regarding the types of immigrants permitted entry into the United States. It defined categories of individuals who could be barred from admission, reflecting growing concerns about immigration and its impact on American society.

A significant outcome of the act was the funding for the construction of the first federal immigration station on Ellis Island in New York Harbor, which would become the nation’s busiest port of entry for immigrants. The law also allocated resources for smaller immigration facilities in other major cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, setting the stage for a more organized and regulated immigration process in the United States, which would continue to evolve in the years to come.

Technology and Military Modernization

During Benjamin Harrison’s presidency, the United States witnessed significant advancements in both technology and military capabilities. Harrison became the first president whose voice was recorded, with a notable thirty-six-second recording made on a wax phonograph cylinder in 1889. He also modernized the White House by installing electricity, although he and his wife refrained from using light switches due to fears of electrocution.

The U.S. Navy, which had languished after the Civil War, underwent significant modernization during Harrison’s administration. He emphasized the need for a robust naval force, influenced by Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan’s influential work, The Influence of Sea Power upon History. Under Secretary of the Navy Tracy, construction of modern warships such as the USS Indiana and USS Texas began, transforming the U.S. into a credible naval power.

Similarly, the U.S. Army, neglected since the Civil War, also sought reform. With Secretary of War Proctor’s initiatives, including improved soldier diets and new promotion systems, desertion rates dropped significantly. However, despite these reforms, the army remained under-equipped compared to European standards by the end of Harrison’s term.

Standardization of Place Names

In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison established the Board on Geographical Names by executive order, aimed at standardizing the spelling of community and municipal names across the United States. This initiative was part of a broader effort to enhance consistency and clarity in geographical references. The board targeted names that featured apostrophes or plurals, converting them into singular forms. For example, Weston’s Mills was changed to Weston Mills, and locations ending in “burgh” were altered to “burg,” leading to a more uniform naming convention.

One notable and controversial decision made by the board involved the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which was briefly renamed to Pittsburg. This change sparked significant backlash from local residents, who continued to use the original spelling. The strong community attachment to the traditional name ultimately led to the reversal of this decision 20 years later, allowing Pittsburgh to retain its historic spelling. Harrison’s standardization efforts reflected a commitment to order and uniformity in federal administration, though they also highlighted the challenges of balancing federal directives with local identity and sentiment.

Foreign Policy under Benjamin Harrison

During his presidency, Benjamin Harrison recognized the rising forces of nationalism and imperialism, which compelled the United States to adopt a more prominent role in global affairs as it experienced significant economic growth. Acknowledging the shortcomings of the existing diplomatic corps, which was often hindered by patronage, Harrison emphasized the importance of a robust consular service to advance American commerce overseas.

In a notable speech in 1891, Harrison declared that the United States had entered a “new epoch” of trade, advocating for an expanding navy to safeguard maritime commerce and enhance American influence internationally. This focus on naval expansion was a response to the need for protection of American shipping interests and demonstrated a commitment to elevating the nation’s status on the world stage.

Reflecting this shift in foreign policy, Congress raised the rank of key diplomatic representatives from minister plenipotentiary to ambassador in 1893, signifying the growing recognition of the United States as a significant player in international relations. Harrison’s administration laid the groundwork for future U.S. involvement in global diplomacy and trade.

Latin American Policy under Benjamin Harrison

President Benjamin Harrison, along with Secretary of State James Blaine, championed an ambitious foreign policy focused on enhancing commercial ties with Latin America. Their objective was to supplant Britain as the leading commercial power in the region. In 1889, Harrison hosted the First International Conference of American States in Washington, aiming to discuss customs and currency integration. Despite the conference’s lack of significant diplomatic breakthroughs, it successfully established an information center that evolved into the Pan American Union.

In the wake of this diplomatic setback, Harrison and Blaine shifted strategies, pursuing tariff reciprocity with Latin American countries. The Harrison administration successfully negotiated eight reciprocity treaties, fostering stronger economic relationships in the region. Notably, they opted not to seek similar agreements with Canada, believing it to be part of the British economic sphere and incompatible with U.S. trade dominance.

Additionally, Harrison appointed Frederick Douglass as ambassador to Haiti, reflecting a commitment to engage more directly with Caribbean nations, although attempts to establish a naval base there were ultimately unsuccessful. This multifaceted approach laid the groundwork for future U.S. engagement in Latin America.

Samoan Crisis during Benjamin Harrison’s Presidency

The Samoan crisis emerged in 1889 as the United States, Great Britain, and Germany vied for control over the strategically important Samoan Islands in the Pacific. The conflict began in 1887 when Germany sought to assert dominance over the islands, prompting President Cleveland to send naval vessels to support the Samoan government. The tensions escalated when American and German warships faced off, but their confrontation was interrupted by the destructive Apia cyclone of March 15–17, 1889, which left both fleets severely damaged.

In response to the growing dispute, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck called for a conference in Berlin to mediate the situation. The resulting Treaty of Berlin established a three-power protectorate over Samoa. Historian George H. Ryden highlights Harrison’s significant role in these negotiations, as he took a firm stance on key issues, including the selection of a local ruler and the rejection of German indemnities.

Ultimately, the crisis fostered long-term American skepticism toward Germany’s foreign policy, especially after Bismarck’s departure from power in 1890. This episode marked a pivotal moment in U.S. foreign relations, demonstrating Harrison’s assertive diplomatic approach.

European Embargo of U.S. Pork during Harrison’s Presidency

In the late 1880s, several European countries, including Germany, imposed an embargo on American pork imports, citing concerns over trichinosis, a parasitic disease linked to undercooked pork. This ban affected over 1.3 billion pounds of pork products, valued at approximately $100 million annually, creating significant economic pressure on American hog farmers.

In response, President Benjamin Harrison took decisive action to protect the U.S. pork industry. He urged Congress to pass the Meat Inspection Act of 1890, which aimed to ensure the quality and safety of American meat products for export. This legislation sought to address the concerns raised by European nations and restore confidence in U.S. pork.

Harrison also directed Agriculture Secretary Jeremiah McLain Rusk to leverage the situation by threatening Germany with retaliation through an embargo on its popular beet sugar exports. This tactic proved effective, and by September 1891, Germany lifted its ban, prompting other countries to follow suit. The resolution of the embargo not only helped stabilize the U.S. pork market but also highlighted Harrison’s proactive approach to international trade and diplomacy.

Crises in the Aleutian Islands and Chile during Harrison’s Presidency

During Benjamin Harrison’s presidency, the U.S. faced two significant international crises: the Aleutian Islands dispute and the Baltimore Crisis in Chile. The first crisis emerged in the early 1890s when Canada claimed fishing rights around the Aleutian Islands, prompting the U.S. Navy to seize several Canadian vessels. Negotiations with the British government ultimately led to a compromise, culminating in international arbitration and compensation paid to the U.S. in 1898.

The second crisis, known as the Baltimore Crisis, erupted in 1891 when sailors from the USS Baltimore were attacked in Valparaíso, Chile. Tensions escalated after the American minister to Chile, Patrick Egan, granted asylum to Chilean rebels during a civil war. Following the assault on Baltimore’s sailors, which the captain claimed was unprovoked, Harrison demanded reparations. When Chilean officials dismissed the claim, Harrison threatened to sever diplomatic relations, emphasizing the need to uphold U.S. prestige. Eventually, the Chilean government issued an apology, averting war. This incident showcased Harrison’s assertive foreign policy approach, earning him praise for effectively navigating a potential conflict.

Vacations and Travel During Harrison’s Presidency

President Benjamin Harrison and his family frequently traveled away from the capital, often incorporating speeches into their itineraries. His notable trips included engagements in cities like Philadelphia, Indianapolis, and Chicago, where he thrived in front of large audiences, preferring such settings over more intimate gatherings. One of his most significant excursions was a five-week tour of the western United States in the spring of 1891, conducted aboard a lavishly outfitted train.

During the sweltering summers in Washington, the Harrisons sought refuge in Deer Park, Maryland, and Cape May Point, New Jersey. In 1890, the Harrisons received a summer cottage at Cape May as a gift from Postmaster General Wanamaker and other Philadelphia supporters. Although Harrison appreciated the gesture, he felt uneasy about the potential for perceived impropriety, leading him to reimburse Wanamaker $10,000 a month later. Despite his efforts to address concerns, the gift sparked national ridicule, drawing fierce criticism from opponents who questioned the ethics of accepting such donations. This episode highlighted the challenges Harrison faced regarding public perception and propriety during his presidency.

Election of 1892

The 1892 presidential election unfolded against a backdrop of economic decline, with the national treasury surplus depleted and the onset of the Panic of 1893 looming. President Benjamin Harrison faced growing dissent within the Republican Party, as influential leaders like Matthew Quay, Thomas Platt, and Thomas Reed formed a Grievance Committee to challenge his leadership. Despite a faction pushing for a run by James Blaine, who ultimately declared himself out of the race, Harrison secured the nomination at the Minneapolis convention. However, Vice President Morton was replaced by Ambassador Whitelaw Reid on the ticket.

The Democrats nominated former President Grover Cleveland, creating a rematch of the 1888 election. Increasing dissatisfaction with high tariffs, exacerbated by rising import costs, fueled voter sentiment for tariff reductions. The Populist Party emerged as a significant third party, nominating James Weaver and advocating for progressive reforms such as free silver and income tax.

Ultimately, Cleveland triumphed decisively, winning 277 electoral votes to Harrison’s 145, marking the most significant margin in two decades. Cleveland garnered 46% of the popular vote, defeating Harrison by about 375,000 votes. The election also resulted in a Democratic majority in both the House and Senate, achieving unified control for the first time since the Civil War.

Historical Reputation of Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison, a one-term president, is often regarded as one of the least notable figures in American presidential history, frequently referred to as the “most forgotten president.” His legacy has been overshadowed by contemporaries, and his tenure is characterized by a lack of significant events, leading to perceptions of mediocrity. While he left office with a relatively intact reputation, the Panic of 1893 prompted a reassessment, with Harrison gaining popularity in retirement as historians largely blamed his successor, Grover Cleveland, for the economic crisis.

Harrison’s ranking among U.S. presidents varies, with many scholars placing him in the middle to lower tiers. Notable polls have ranked him between the 30th and 34th best president out of 45, highlighting a perception of his presidency as average. Critics have described him as a “lightweight puppet of party bosses,” and many history textbooks provide little more than unflattering mentions.

Despite the lack of attention to his presidency, recent historians have acknowledged Harrison’s role in shaping late 19th-century foreign policy, particularly in trade negotiations and the expansion of the Navy. His signing of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, which remains in effect today, and his conservation efforts laid groundwork for future administrations. Harrison’s advocacy for African American voting rights marked significant progress in civil rights, though his policies toward Native Americans, especially during the Wounded Knee Massacre, have drawn criticism.

Overall, Harrison’s administration is remembered for its contributions to foreign policy and civil rights, albeit marred by challenges and controversies, leaving a mixed legacy that continues to be evaluated by historians.