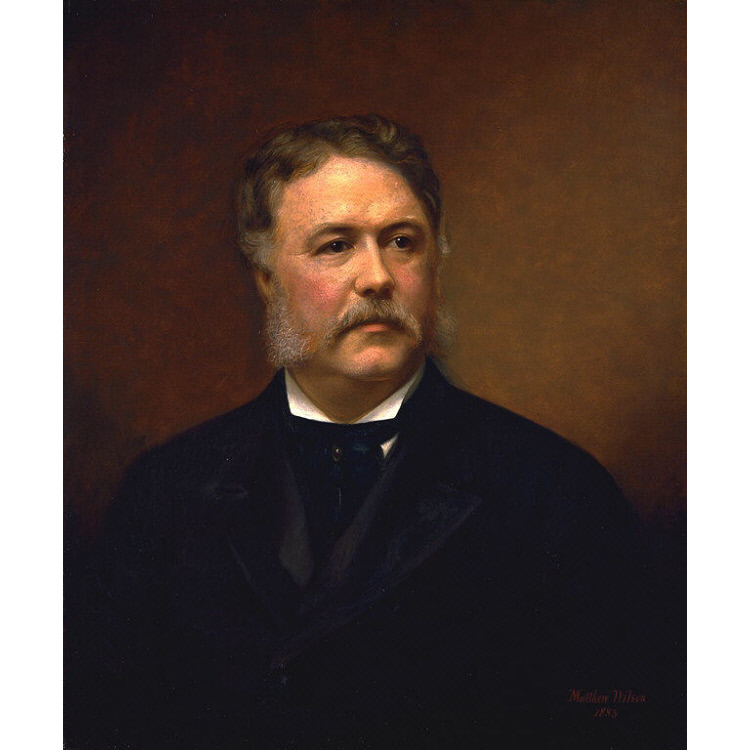

Chester Alan Arthur, born on October 5, 1829, and passing on November 18, 1886, was the 21st president of the United States, serving from 1881 to 1885. A Republican lawyer from New York, Arthur initially held the position of vice president under James A. Garfield. However, after Garfield’s tragic assassination, Arthur took on the role of president, serving out the remainder of the term until March 4, 1885.

Arthur’s roots were in Fairfield, Vermont, though he spent much of his youth in upstate New York before becoming a lawyer in New York City. During the American Civil War, he served as quartermaster general for the New York Militia. Post-war, he became increasingly involved in New York Republican politics, quickly rising within Senator Roscoe Conkling’s powerful political organization.

His influence earned him an appointment from President Ulysses S. Grant as Collector of the Port of New York in 1871, where he played a crucial role supporting Conkling and the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party. However, in 1878, Arthur found himself caught in the crossfire of a political dispute between Conkling and President Rutherford B. Hayes over federal patronage in New York. As part of Hayes’ reforms, Arthur was removed from his position.

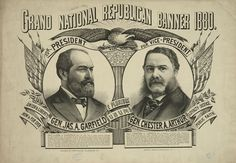

In 1880, the Republican Party found itself divided between the Stalwarts, who backed Ulysses S. Grant, and the Half-Breeds, who supported James G. Blaine. As a compromise, the party chose Ohio’s James A. Garfield as their presidential candidate, while Arthur was nominated as vice president to balance the ticket. Their victory in the 1880 election saw Garfield and Arthur assume office in March 1881. Unfortunately, just four months later, Garfield was shot by an assassin and succumbed to his injuries after 11 weeks, elevating Arthur to the presidency.

Chester Alan Arthur was the 21st president of the US war (topicsxpress.com)

As president, Arthur focused on modernizing the U.S. Navy but faced criticism for not addressing the growing federal budget surplus, a legacy of the Civil War. He initially vetoed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act due to concerns over its conflict with the Burlingame Treaty, though he eventually signed a revised version with a ten-year ban on Chinese immigration. Arthur also made notable judicial appointments, including Horace Gray and Samuel Blatchford to the Supreme Court.

His administration enacted further restrictions on immigration through the Immigration Act of 1882 and addressed tariff issues with the Tariff of 1883. Despite his earlier ties to political patronage, Arthur signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883, a move that surprised many who viewed him as a staunch Stalwart.

Plagued by health issues, Arthur made little effort to secure the Republican nomination in 1884 and chose to retire at the end of his term. His presidency, though less active by modern standards, earned him respect from contemporaries. Journalist Alexander McClure once remarked, “No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted as Chester Alan Arthur, and no one ever retired … more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe.”

The New York World, upon his death in 1886, summed up his presidency by stating, “No duty was neglected in his administration, and no adventurous project alarmed the nation.” Even Mark Twain praised him, saying, “It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur’s administration.” However, modern historians tend to rank Arthur as an average president, with some labeling him as one of the least memorable.

Early Life

Birth and Family Chester Alan Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur was born in the small town of Fairfield, Vermont, to Malvina Stone and William Arthur. His mother, Malvina, hailed from Berkshire, Vermont, and came from a family with deep roots in America, primarily of English and Welsh ancestry. Her maternal grandfather, Uriah Stone, had even served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

Chester Alan Arthur father, William, was born in 1796 in Dreen, Cullybackey, County Antrim, Ireland, to a Presbyterian family of Scots-Irish descent. William’s mother, Eliza McHarg, married Alan Arthur, and together they raised their family in Ireland before William decided to pursue higher education. After graduating from college in Belfast, William migrated to Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) around 1819 or 1820.

William met Malvina Stone while teaching in Dunham, Quebec, near the Vermont border. Their courtship was swift, and the couple married on April 12, 1821, shortly after meeting. Following their marriage, the Arthurs moved to Vermont, where their first child, Regina, was born. The family soon found themselves moving frequently across Vermont as William took up various teaching positions in Burlington, Jericho, and Waterville.

During their time in Waterville, William Arthur briefly studied law but soon shifted his focus. He left behind both his legal ambitions and his Presbyterian upbringing, embracing the Free Will Baptists. He spent the rest of his life as a minister in that denomination, becoming a fervent abolitionist, a stance that often made him unpopular in some communities. This, along with his ministry, led to the family’s constant relocations.

In 1828, the Arthur family settled in Fairfield, Vermont, where Chester Alan Arthur was born the following year as the fifth of nine children. His first name honored Chester Abell, a physician and family friend who assisted in his birth, while his middle name, Alan, paid tribute to his paternal grandfather.

The family remained in Fairfield until 1832 before moving to various towns across Vermont and upstate New York, following William Arthur’s ministry work. They finally settled in Schenectady, New York, in 1844, where Chester spent much of his formative years.

Siblings

Chester Arthur was one of nine children, seven of whom lived to adulthood:

- Regina (1822–1910): Married William G. Caw, a grocer, banker, and community leader in Cohoes, New York.

- Jane (1824–1842): Passed away at a young age.

- Almeda (1825–1899): Married James H. Masten, who served as postmaster of Cohoes and was the publisher of the Cohoes Cataract newspaper.

- Ann (1828–1915): A dedicated educator who taught in New York and worked in South Carolina during the Civil War era.

- Malvina (1832–1920): Married Henry J. Haynesworth, an official in the Confederate government who later served as a U.S. Army captain during Chester Arthur’s presidency.

- William (1834–1915): A medical school graduate who served as a career Army officer and paymaster. He was wounded during the Civil War and retired in 1898 with the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel.

- George (1836–1838): Died as an infant.

- Mary (1841–1917): Married John E. McElroy, an Albany businessman. During Chester Arthur’s presidency, she served as the official White House hostess.

Rumors and Citizenship Controversy

The Arthur family’s frequent relocations later became the foundation for rumors surrounding Chester Arthur’s place of birth. When he was nominated as vice president in 1880, a political opponent, attorney Arthur P. Hinman, speculated that Arthur had been born in Ireland and only arrived in the United States at the age of 14. This claim suggested that Arthur might be ineligible for the vice presidency under the Constitution’s natural-born-citizen clause.

When this rumor failed to gain traction, Hinman circulated a new theory: Arthur had been born in Canada, not Vermont. However, this claim also lacked credibility and was eventually dismissed. Despite these controversies, Arthur’s birth in Fairfield, Vermont, was never successfully disputed.

Education

Chester Alan Arthur spent much of his childhood moving around New York, living in towns such as York, Perry, Greenwich, Lansingburgh, Schenectady, and Hoosick. Described by one of his early teachers as a boy with “frank and open manners” and a “genial disposition,” Arthur began to develop an interest in politics during his school years. He supported the Whig Party and even got involved in a brawl with students who backed James K. Polk during the 1844 presidential election, while he rooted for Henry Clay. Arthur also showed his support for the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish republican organization, by proudly wearing a green coat.

After completing his preparatory studies at the Lyceum of Union Village (now Greenwich) and a grammar school in Schenectady, Arthur enrolled at Union College in 1845. At Union, he pursued a traditional classical education and became a member of the Psi Upsilon fraternity. Arthur’s academic achievements didn’t stop there; he was elected president of the debate society as a senior and earned a spot in the prestigious Phi Beta Kappa society. During winter breaks, Arthur taught at a school in Schaghticoke, gaining early experience in education.

After graduating from Union College in 1848, Arthur returned to Schaghticoke to work as a full-time teacher, though his ambitions quickly turned toward law. While studying law, he continued teaching and eventually moved closer to home, securing a teaching job in North Pownal, Vermont. Interestingly, future President James A. Garfield would also teach at this school three years later, though their paths never crossed.

In 1852, Arthur moved to Cohoes, New York, to take on the role of principal at a school where his sister, Malvina, was a teacher. The following year, after studying at the State and National Law School in Ballston Spa, New York, and saving enough money to move to New York City, Arthur began reading law under the guidance of Erastus D. Culver, a well-known abolitionist lawyer and family friend. By 1854, Arthur was admitted to the New York bar and became a partner in Culver’s firm, which was renamed Culver, Parker, and Arthur.

Early Career: New York Lawyer

Chester Alan Arthur legal career took off when he joined Culver’s firm. One of the significant cases he was involved in was Lemmon v. New York, where Culver and John Jay (the grandson of the Founding Father) argued that any slave brought into New York, where slavery was illegal, should be considered free. Although Arthur’s role in this case was relatively minor, campaign biographies later gave him more credit than he likely deserved. Nonetheless, the case was a significant win for civil rights and was upheld by the New York Court of Appeals in 1860.

Arthur also made a name for himself by winning a civil rights case in 1854. He successfully represented Elizabeth Jennings Graham, a Black woman who was forcibly removed from a streetcar. This victory led to the desegregation of New York City’s streetcar lines, marking a pivotal moment in the fight for equal rights.

In 1856, Arthur began courting Ellen Herndon, the daughter of a Virginia naval officer, and the two soon became engaged. That same year, Arthur formed a new law partnership with Henry D. Gardiner, and the two traveled to Kansas to explore opportunities for land and a potential law practice. However, the rough frontier life didn’t suit these New Yorkers, and they quickly returned to New York City.

Chester Alan Arthur fiancée, Ellen, suffered a personal tragedy when her father was lost at sea in the wreck of the SS Central America. In 1859, the couple married at Calvary Episcopal Church in Manhattan. They had three children, though their first child, William Lewis Arthur, tragically passed away at the age of two. Their second child, Chester Alan Arthur II, and their daughter, Ellen Hansbrough Herndon “Nell” Arthur Pinkerton, both survived to adulthood.

Despite the personal tragedies, Arthur continued to build his law practice while becoming increasingly involved in Republican Party politics. He also pursued his military interests, eventually becoming the Judge Advocate General for the Second Brigade of the New York Militia.

Civil War and Military Career

In 1861, as the Civil War broke out, Arthur was appointed as engineer-in-chief on the military staff of New York Governor Edwin D. Morgan. This seemingly minor patronage role became critical when New York and other Northern states needed to raise and equip vast armies. Arthur was promoted to brigadier general and tasked with managing the state’s quartermaster department, where he efficiently outfitted the troops. His success led to further promotions, first as inspector general of the state militia in March 1862 and then as quartermaster general in July of that year.

Though he had opportunities to command troops at the front, Arthur chose to remain in New York at Governor Morgan’s request. The closest he came to battle was during a visit to inspect New York troops in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1862. That summer, Arthur worked with other Northern governors and Secretary of State William H. Seward to raise more troops for the war effort. His work earned him widespread praise, but when Democrat Horatio Seymour became governor in 1863, Arthur lost his political appointment.

Arthur returned to his law practice, which thrived thanks to the connections he had made during his military service. However, the loss of his young son, William, in 1863 was a significant personal blow. Arthur and his wife devoted themselves to their remaining children, Chester Jr. and Ellen.

Arthur’s political fortunes improved with the election of his mentor, ex-Governor Morgan, to the United States Senate. He also formed alliances with influential figures like Thomas Murphy, a Republican politician and businessman with ties to Tammany Hall. Arthur and Murphy became key players in New York’s Republican Party, aligning themselves with the conservative faction led by Thurlow Weed. In the 1864 presidential election, Arthur and Murphy helped raise funds for the Republican cause and attended Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration in 1865.

New York Politician

Conkling’s Machine

With the conclusion of the Civil War, new opportunities emerged for members of Morgan’s Republican machine, including Chester A. Arthur. This machine, led by influential figures like Roscoe Conkling, a prominent Congressman from Utica, operated within the conservative wing of the New York Republican Party. Arthur, who had been an active participant in this political network, focused more on loyalty and diligent work for the machine than on articulating his own political beliefs.

In 1866, Arthur made an unsuccessful bid for the position of Naval Officer at the New York Custom House, a prestigious role just below the Collector. Despite this setback, he continued his legal practice, now operating solo following Gardiner’s death, and maintained his political involvement. By 1867, Arthur had joined the esteemed Century Club and was rising through the ranks of the Republican Party. His connection with Conkling, who became a U.S. Senator in 1867, further bolstered his political career, culminating in his appointment as chairman of the New York City Republican executive committee in 1868.

As Conkling solidified his control over New York’s conservative Republicans, Morgan shifted his focus to national politics, serving as chairman of the Republican National Committee. Conkling’s machine threw its full support behind General Ulysses S. Grant’s presidential bid in 1868. Arthur played a key role in fundraising for Grant’s campaign. Although Grant won the presidency, his opponent, Horatio Seymour, narrowly won New York State.

Chester Alan Arthur political commitments began to overshadow his legal practice. In 1869, he took on the role of counsel to the New York City Tax Commission, a position secured during a period of Republican dominance in the state legislature. He held this role until 1870, earning a salary of $10,000 per year. When the Democrats, led by Tammany Hall’s William M. Tweed, gained control of the legislature, Arthur was forced to resign.

In 1871, despite Grant’s offer of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue position, Arthur declined. However, his fortunes changed later that year when Grant appointed him as Collector of the New York Custom House. The Custom House, a significant political and financial hub, managed the United States’ busiest port and its extensive tariff collection operations.

Chester Alan Arthur appointment was facilitated by Conkling, who was influential in New York patronage. Initially, Arthur’s salary was $6,500, but he also benefited from the “moiety” system, which granted a percentage of fines and cargoes seized, significantly boosting his income. At the height of his career, Arthur’s earnings exceeded $50,000 annually, surpassing the president’s salary and allowing him to enjoy a lavish lifestyle. His tenure as Collector was marked by relative popularity among his subordinates, partly because he inherited a staff already loyal to Conkling and made few changes.

Chester Alan Arthur reputation improved compared to his predecessor, Thomas Murphy, who had been tainted by his connections to Tammany Hall and his role as a war profiteer. Despite Arthur’s popularity, the patronage system and moiety structure faced criticism from reformers. In 1872, Arthur renamed the financial contributions from employees to “voluntary contributions” to deflect criticism, but the essence of the system remained unchanged.

The push for civil service reform continued to challenge Conkling’s machine. By 1874, Congress intervened after Custom House employees were found to have abused the moiety system, leading to its repeal and a switch to regular salaries. Consequently, Arthur’s income was reduced to $12,000 per year, which, while still more than his nominal boss, the Secretary of the Treasury, was considerably less than what he had previously earned.

Clash with Hayes

Chester Alan Arthur four-year term as Collector ended on December 10, 1875, and with Conkling’s influence, he secured reappointment from President Grant. Conkling was a prominent figure at the 1876 Republican National Convention but lost the presidential nomination to reformer Rutherford B. Hayes. While Arthur and the machine were active in campaign fundraising, Conkling’s involvement was limited to a few speeches.

Hayes, who entered office with a reformist agenda, targeted Conkling’s machine for reform. In 1877, Treasury Secretary John Sherman initiated an investigation into the New York Custom House, revealing that a significant portion of its staff were politically appointed and expendable. Sherman, though not fully supportive of the reforms, approved the report and instructed Arthur to implement staff reductions. Arthur complied, but the commission’s follow-up reports criticized the Custom House and called for more extensive reorganization.

Hayes’s executive order banning political assessments and limiting federal officeholders’ political involvement further strained relations. Arthur, along with his colleagues, resisted these changes, leading Hayes to demand their resignations in September 1877. When the Senate, controlled by Conkling, rejected Hayes’s nominees to replace Arthur and his team, Hayes ultimately dismissed them during a Congressional recess in July 1878. Arthur was offered a consulship in Paris as a consolation but declined.

Chester Alan Arthur subsequent efforts included working for the election of Edward Cooper as New York City’s mayor and serving as chairman of the New York State Republican Executive Committee until October 1881. Despite a personal tragedy with his wife’s sudden death in January 1880, Arthur continued his political activities.

Election of 1880

In the 1880 Republican National Convention, Conkling and the Stalwarts aimed to nominate ex-President Grant. However, the deadlocked convention turned to James A. Garfield, a dark horse candidate. Garfield, aware of the challenge without New York Stalwart support, offered the vice-presidential nomination to Arthur. Despite Conkling’s advice to decline, Arthur accepted, believing it to be a significant honor.

The election was close, with Garfield and Arthur narrowly winning against Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock. Chester Alan Arthur played a crucial role in the campaign, managing efforts in New York and raising vital funds, which helped secure the state and the overall victory.

Vice Presidency (1881)

After the election, Chester Alan Arthur struggled to persuade Garfield to appoint Stalwarts to key positions. Garfield’s cabinet appointments and Arthur’s own speech suggesting illegal activities in Indiana led to strained relations between the two. As vice president, Arthur cast tie-breaking votes in favor of Republicans but found his influence waning.

When Garfield was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, who believed Chester Alan Arthur would become president, there was uncertainty about presidential succession. Arthur, reluctant to act while Garfield was alive, faced a legal and political void. After Garfield’s death on September 19, Arthur was sworn in as president by Judge John R. Brady at his home on September 20. He promptly traveled to Garfield’s funeral and took steps to ensure the continuity of presidential succession.

Taking Office

Chester Alan Arthur assumed the presidency on September 21, 1881, following the assassination of President James A. Garfield. To ensure procedural correctness, Arthur retook the oath of office on September 22 before Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite. This step was taken to address any concerns about whether a state court judge could validly administer the federal oath of office. Initially, Arthur lived with Senator John P. Jones while extensive renovations were completed at the White House. These renovations included the addition of a grand fifty-foot glass screen designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany, reflecting the era’s opulence and Arthur’s desire for a modernized executive residence.

Cabinet Changes

Chester Alan Arthur presidency began with significant changes in his cabinet. Many of Garfield’s appointees were opponents of Arthur within the Republican Party. Arthur initially requested that these cabinet members stay on until December, when Congress reconvened. However, key resignations soon followed. Treasury Secretary William Windom resigned in October 1881 to run for the Senate in Minnesota, prompting Arthur to appoint his friend and fellow New York Stalwart, Charles J. Folger, as his replacement.

Attorney General Wayne MacVeagh, a reformist, also resigned in December 1881, citing incompatibility with Arthur’s administration. Despite Arthur’s personal appeals, MacVeagh was replaced by Benjamin H. Brewster, a Philadelphia lawyer known for his reformist tendencies. Arthur’s attempts to balance his cabinet were further complicated by the departure of Secretary of State James G. Blaine, who was succeeded by Frederick T. Frelinghuysen of New Jersey, a Stalwart recommended by former President Ulysses S. Grant.

Chester Alan Arthur continued to navigate the political landscape by appointing Timothy O. Howe, a Wisconsin Stalwart, as Postmaster General following James’s resignation in January 1882. When Navy Secretary William H. Hunt resigned in April 1882, Arthur chose William E. Chandler, a Half-Breed reformer recommended by Blaine, for the position. Arthur also appointed Henry M. Teller, a Colorado Stalwart, as Secretary of the Interior after Samuel J. Kirkwood’s resignation. Of the original Garfield cabinet members, only Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln remained throughout Arthur’s term. The inability to appoint a new vice president was a limitation of the period, as the 25th Amendment to the Constitution had not yet been ratified.

Civil Service Reform

Chester Alan Arthur presidency marked a significant shift in the realm of civil service reform. The administration was initially met with skepticism due to Arthur’s past as a supporter of the spoils system. However, his Attorney General, Benjamin Brewster, continued investigations into the star route scandal, which involved overpayment of contractors with the complicity of government officials. Despite challenges, including a hung jury and allegations of jury tampering, Arthur supported the investigation and managed to force the resignation of implicated officials.

The assassination of Garfield intensified public demand for civil service reform. Both Democratic and Republican leaders recognized the opportunity to appeal to reform-minded voters. In 1880, Democratic Senator George H. Pendleton introduced a bill requiring merit-based selection for civil service positions. Chester Alan Arthur supported this reform and requested similar legislation in his 1881 annual message to Congress. Although the bill was not initially passed, the 1882 elections shifted the political landscape, leading to the enactment of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act on January 16, 1883. The act initially applied to only 10% of federal jobs but laid the groundwork for a merit-based system.

Chester Alan Arthur commitment to reform was demonstrated by his swift appointment of a Civil Service Commission and his support for the new system’s implementation. By 1884, a significant portion of federal jobs were awarded based on merit rather than political connections. Arthur expressed satisfaction with the system, highlighting its effectiveness in ensuring competent public servants and reducing political influence in hiring.

Economic Policies

Chester Alan Arthur faced a substantial federal surplus, accumulated from wartime taxes, by 1882. With a surplus of $145 million, there was debate on how to address it. Democrats advocated for lower tariffs to reduce revenue and the cost of imports, while Republicans supported high tariffs to protect American industries and reduce excise taxes.

Chester Alan Arthur, aligning with his party, called for the abolition of excise taxes on all goods except liquor and sought to simplify the tariff system. In May 1882, Representative William D. Kelley introduced a bill to establish a tariff commission, which Arthur signed into law. However, the commission’s recommendations for significant tariff reductions were ignored, and a more modest reduction of 1.47% was passed.

Congress also attempted to balance the budget by increasing spending on internal improvements, including the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1882, which proposed $19 million in spending. Arthur vetoed the bill, citing its focus on specific localities rather than national benefits. Although Congress overrode his veto, the additional spending contributed to the Republican Party’s loss in the 1882 elections.

Foreign Affairs and Immigration

Chester Alan Arthur foreign policy focused on strengthening U.S. diplomacy in Latin America, continuing the efforts of his predecessor, James G. Blaine. Despite these efforts, many of Blaine’s initiatives, including a Pan-American conference and reciprocal trade agreements, failed to materialize during Arthur’s presidency.

Domestically, Arthur signed the Immigration Act of 1882, which imposed a tax on immigrants and excluded certain groups, including the mentally ill and criminals. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was a more contentious issue. Initially vetoing a twenty-year exclusion of Chinese laborers, Arthur ultimately signed a ten-year exclusion act after Congress made compromises. This act was intended to restrict Chinese immigration but was widely evaded.

Naval Resurgence

Chester Alan Arthur administration prioritized the modernization of the U.S. Navy, which had declined significantly since the Civil War. Arthur supported the creation of a stronger navy to project American power beyond coastal waters. Secretary of the Navy William E. Chandler, appointed by Arthur, played a key role in this effort. Chandler’s administration saw the construction of the “ABCD Ships”—three steel-protected cruisers and an armed dispatch-steamer.

Although faced with opposition, especially from Democrats, Arthur’s efforts laid the foundation for future naval expansion. The Navy’s modernization, despite some setbacks, improved its capabilities and efficiency. Chandler’s work, including the establishment of the Naval War College, contributed significantly to the Navy’s resurgence.

During Chester Alan Arthur term, the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, a scientific polar exploration, set a new Farthest North record. Despite achieving significant exploration milestones, the expedition faced severe hardships, with only seven of the original twenty-five crew members surviving to return.

Civil Rights

The Readjuster Party’s Impact

Chester Alan Arthur grappled with the challenge of how to address civil rights in the South amidst a rapidly changing political landscape. Following the end of Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats, known as “Bourbon Democrats,” reasserted control over the South, leading to the rapid decline of the Republican Party in the region. Black southerners, who had been a primary support base for the Republicans, were increasingly disenfranchised.

In Virginia, however, a new political force emerged—the Readjuster Party, led by William Mahone. This party gained traction by advocating for more educational funding for both Black and white schools and calling for the abolition of discriminatory practices like the poll tax and the whipping post. Recognizing the Readjusters as a more promising ally than the beleaguered southern Republicans, Arthur chose to direct federal patronage through them in Virginia. He adopted a similar strategy in other Southern states, forming coalitions with independents and members of the Greenback Party.

Although this approach was somewhat controversial, it did find support among some Black Republicans. Figures like Frederick Douglass and former Senator Blanche K. Bruce endorsed Arthur’s strategy, seeing the Readjusters as a preferable alternative to the conservative Democrats. Despite these efforts, the coalition policy only yielded limited success. By 1885, the Readjuster movement began to falter with the election of a Democratic president, and the Republican Party’s influence continued to wane.

Federal actions to advance civil rights were similarly limited. When the Supreme Court invalidated the Civil Rights Act of 1875 in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, Arthur expressed his disagreement with the ruling in a message to Congress. However, he was unable to convince Congress to pass new legislation to replace it. On a more positive note, Chester Alan Arthur intervened to overturn a racially biased court-martial decision against a Black West Point cadet, Johnson Whittaker. The Judge Advocate General of the Army, David G. Swaim, found the prosecution’s case to be illegal and racially prejudiced, leading to a successful intervention by the administration.

Native American Policy

Chester Alan Arthur presidency was marked by evolving relations with western Native American tribes as the American Indian Wars drew to a close and public opinion shifted toward more favorable treatment of Native Americans. Arthur advocated for increased funding for Native American education, which Congress partially addressed in 1884, though not to the extent he had hoped.

Chester Alan Arthur also supported the idea of an allotment system, where individual Native Americans rather than tribes would own land. Although he was unable to persuade Congress to adopt this system during his term, the Dawes Act of 1887 eventually implemented it. Initially supported by liberal reformers, the allotment system ultimately proved harmful as much of the land was sold off at low prices to white speculators.

During Arthur’s presidency, settlers and cattle ranchers continued to encroach upon Native American territories. Although Arthur initially resisted these encroachments, he eventually opened the Crow Creek Reservation in the Dakota Territory to settlers by executive order in 1885, following assurances from Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller that the lands were not adequately protected. This order was later revoked by Arthur’s successor, Grover Cleveland, who recognized the Native Americans’ rightful claim to the land.

Health and Travel

Shortly after becoming president, Chester Alan Arthur was diagnosed with Bright’s disease, now known as nephritis. He attempted to keep his condition private, but by 1883, his deteriorating health became apparent. To improve his well-being, Arthur and some political friends traveled to Florida in April 1883. Unfortunately, the trip exacerbated his condition, leading to intense pain and a return to Washington.

Later in 1883, on the advice of Senator George Graham Vest, Arthur visited Yellowstone National Park. The trip, which was also intended to publicize the newly established National Park system, was more beneficial to his health than his earlier Florida excursion. Arthur returned to Washington refreshed after spending two months in the park.

1884 Presidential Election

As the 1884 presidential election approached, James G. Blaine was the favored candidate for the Republican nomination. Although Arthur considered running for a full term, he soon realized that he lacked the full support of the Republican Party. The Half-Breeds were solidly behind Blaine, while the Stalwarts were divided between Arthur and Senator John A. Logan of Illinois. Reform-minded Republicans, who had become more favorable towards Arthur after his endorsement of civil service reform, were still not fully convinced of his commitment compared to Senator George F. Edmunds of Vermont.

Business leaders and Southern Republicans who benefited from Arthur’s control of patronage supported him, but by the time they began to rally around him, Arthur decided against a serious campaign for the nomination. He maintained a token effort to avoid raising doubts about his actions in office or his health. By the time of the Republican National Convention in June, his defeat was inevitable. Blaine secured the nomination on the fourth ballot with a majority of 541 votes, while Chester Alan Arthur received only 207. Arthur graciously congratulated Blaine and accepted his defeat. He played no role in the campaign, which Blaine later attributed to his loss in November to Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland.

Judicial Appointments

Chester Alan Arthur made significant appointments to the United States Supreme Court during his presidency. The first vacancy arose in July 1881 with the death of Associate Justice Nathan Clifford. Arthur nominated Horace Gray, a distinguished jurist from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Gray’s nomination was confirmed easily, and he served on the Court for over 20 years until his resignation in 1902.

The second vacancy occurred when Associate Justice Ward Hunt retired in January 1882. Arthur initially nominated his former political boss, Roscoe Conkling, though he doubted Conkling would accept. Conkling declined the nomination, making it the last instance of a confirmed nominee refusing an appointment. Arthur then nominated Senator George Edmunds, who also declined. Samuel Blatchford, a judge on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, was ultimately appointed. His nomination was approved by the Senate within two weeks, and he served on the Court until his death in 1893.

Post-Presidency (1885–1886)

After leaving the presidency in 1885, Chester Alan Arthur returned to his New York City home. Although several New York Stalwarts approached him to run for the United States Senate, Arthur declined, opting instead to return to his former law practice with Arthur, Knevals & Ransom. However, his health limitations restricted his activity at the firm, and he served only as of counsel. Arthur took on few assignments and was often too ill to leave his home, managing only a few public appearances until the end of 1885.

Death

In the summer of 1886, Arthur spent time in New London, Connecticut, but upon returning home, his health deteriorated significantly. On November 16, he ordered that nearly all of his personal and official papers be burned. The next morning, Arthur suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and did not regain consciousness. He passed away on November 18 at the age of 57.

Chester Alan Arthur funeral, held on November 22, was a private affair at the Church of the Heavenly Rest in New York City. The service was attended by notable figures, including President Grover Cleveland and former President Rutherford B. Hayes. Arthur was buried at the Albany Rural Cemetery in Menands, New York, alongside his family members and ancestors. His grave was marked by a large sarcophagus, and in 1889, sculptor Ephraim Keyser created a monument featuring a giant bronze female angel placing a palm leaf on the granite sarcophagus.

Chester Alan Arthur post-presidency was notably brief, the second shortest of any president who lived beyond their term, after James K. Polk.

Legacy

Chester Alan Arthur legacy is reflected in various memorials and honors. Several Grand Army of the Republic posts were named in his honor, including locations in Goff, Kansas; Lawrence, Nebraska; Medford, Oregon; and Ogdensburg, Wisconsin. On April 5, 1882, he was elected to the District of Columbia Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) as a Third Class Companion, an honor recognizing significant contributions to the Union during the Civil War.

Union College awarded Arthur an honorary LL.D. degree in 1883. In 1898, a statue of Arthur was erected at Madison Square in New York City. Sculpted by George Edwin Bissell, the fifteen-foot bronze statue was dedicated in 1899 and unveiled by Arthur’s sister, Mary Arthur McElroy. Secretary of War Elihu Root, at the dedication, described Arthur as wise in statesmanship and firm in administration, though acknowledging his isolation in office and lack of party support.

In 1938, fifty-two years after Arthur’s death, the U.S. Post Office issued a definitive stamp in his honor. Additionally, Arthur appeared on a U.S. one-dollar coin in 2012.

Despite his general unpopularity during his presidency, which affected his historical reputation, there has been a reassessment of his legacy over time. Historian George F. Howe noted Arthur’s significant, though often overlooked, role in American history. Thomas C. Reeves later praised Arthur for his sound appointments and his ability to maintain integrity despite the corruption and scandal prevalent during his era. Biographer Zachary Karabell acknowledged Arthur’s efforts to do right by the country despite his personal challenges. Howe also remarked on Arthur’s adherence to personal principles, distinguishing him from the typical politician of his time.

Arthur’s former townhouse, known as the Chester A. Arthur Home, was sold to William Randolph Hearst and since 1944 has been the location of Kalustian’s Spice Emporium.