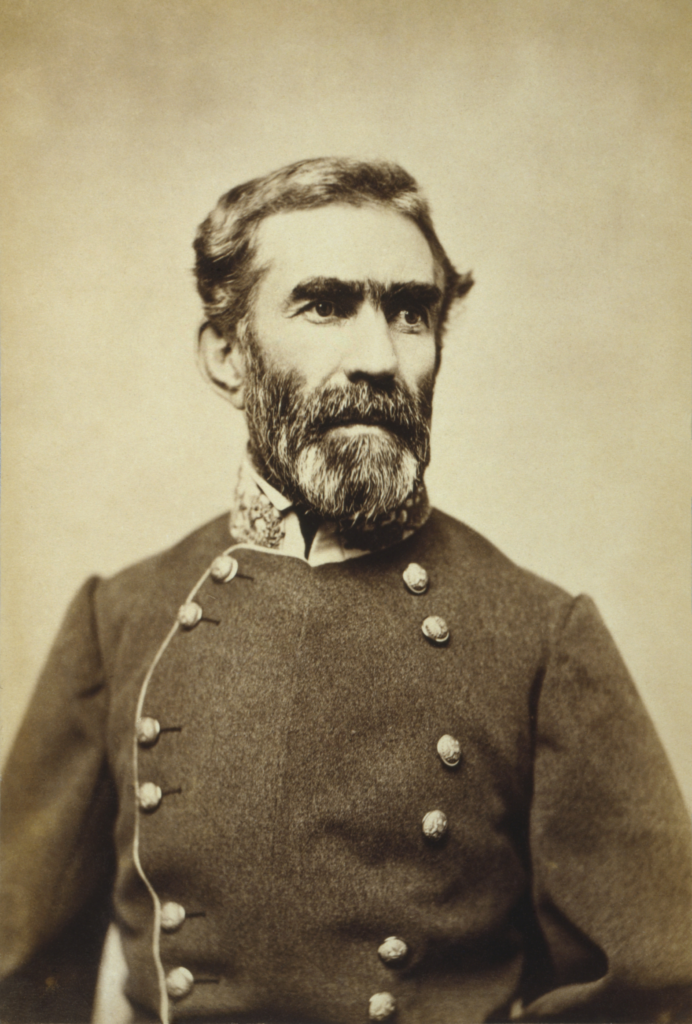

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th President of the United States. His presidency, spanning from March to September 1881, was tragically cut short by assassination. Before his presidency, Garfield had a varied career as a preacher, lawyer, and Union general during the Civil War. He served nine terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, making him the only sitting House member ever elected to the presidency. Although he was also elected to the U.S. Senate by Ohio’s General Assembly, he declined the position when he became president-elect.

Born in a log cabin in northeastern Ohio, Garfield grew up in poverty. He later graduated from Williams College, studied law, and became an attorney. His early career included roles as a preacher in the Stone-Campbell Movement and as president of the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, which was affiliated with the Disciples. In 1859, he was elected to the Ohio State Senate, where he served until 1861.

James Abram Garfield was the 20th President of the

Garfield was a staunch opponent of Confederate secession and served as a major general in the Union Army, participating in key battles such as Middle Creek, Shiloh, and Chickamauga. Elected to Congress in 1862, he represented Ohio’s 19th district and gained a reputation as a strong orator and supporter of the gold standard.

Initially aligned with Radical Republican views on Reconstruction, he later supported a more moderate approach to civil rights for freed slaves. Notably, Garfield demonstrated his mathematical skills by publishing his own proof of the Pythagorean theorem in 1876.

At the 1880 Republican National Convention, James Abram Garfield was selected as a compromise candidate for president on the 36th ballot, despite not actively seeking the position. His campaign was low-key, and he narrowly defeated Democratic nominee Winfield Scott Hancock. As president, Garfield made significant strides, including asserting presidential authority over Senate appointments, addressing corruption in the Post Office, and appointing a Supreme Court justice. He championed agricultural innovation, an educated electorate, and civil rights for African Americans, and he advocated for civil service reform, which was later enacted as the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act by his successor, Chester A. Arthur.

James Abram Garfield was part of the “Half-Breed” faction within the Republican Party and used his presidential influence to challenge the powerful “Stalwart” Senator Roscoe Conkling by appointing William H. Robertson, a leader in the Blaine faction, to the lucrative position of Collector of the Port of New York. This move led to a political clash, resulting in Robertson’s confirmation and the resignations of Conkling and Thomas C. Platt from the Senate.

On July 2, 1881, James Abram Garfield was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, a disaffected office seeker, at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington. Although the wound was not immediately fatal, Garfield’s death on September 19 was ultimately caused by an infection resulting from his doctors’ unsanitary practices. Despite his brief time in office, James Abram Garfield is remembered for his efforts against corruption and his commitment to civil rights, though historians often rank him as a below-average president due to his short tenure.

Early Years and Family Roots James Abram Garfield

James Abram Garfield, born on November 19, 1831, in a modest log cabin in Orange Township (now Moreland Hills), Ohio, was the youngest of five children. His ancestry traces back to Edward Garfield, who emigrated from Hillmorton, England, to Massachusetts around 1630. James’s father, Abram, moved to Ohio with hopes of marrying his childhood sweetheart, Mehitabel Ballou. When he discovered she was married, he wed her sister Eliza instead. James was named in honor of an older sibling who had passed away in infancy.

In 1833, the James Abram Garfield family joined a Stone-Campbell church, which had a lasting impact on James’s life. Sadly, Abram died that same year, leaving Eliza to raise her children in difficult circumstances. Despite these hardships, James was very close to his mother, and her stories about their Welsh heritage and notable ancestors were a source of inspiration for him.

Growing up in poverty, James Abram Garfield was often teased by his peers, which made him sensitive to criticism. He found solace in reading extensively. At 16, he left home in 1847 and initially struggled to find work, eventually taking a job managing mules on a canal boat. After falling ill, he returned home, and his mother, along with a local educator, persuaded him to focus on his education rather than returning to canal work.

Education, Marriage, and Early Career

James Abram Garfield began his formal education in 1848 at Geauga Seminary in Chester Township, Ohio. He excelled academically and developed a keen interest in languages and oratory. It was here that he met Lucretia Rudolph, who would later become his wife. To support himself, Garfield worked as a carpenter’s assistant and a teacher, though he found the constant need to find teaching positions challenging. Despite this, he was committed to his studies and later described his early years as a struggle but a formative period of growth.

In 1851, James Abram Garfield enrolled at the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later known as Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio, where he studied Greek and Latin. He also worked as a janitor and a teacher at the Institute. During this time, he also began preaching at nearby churches, earning a modest fee for his services. By 1854, he had completed his studies at the Institute and continued his education at Williams College in Massachusetts, where he was warmly received by the college president, Mark Hopkins. James Abram Garfield graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Williams in August 1856, serving as salutatorian and speaking at the commencement ceremony.

After returning to Ohio, Garfield took on the role of principal at the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute. He became involved in politics, campaigning for Republican presidential candidate John C. Frémont in 1856. In 1858, he married Lucretia Rudolph, and they had seven children, with five surviving infancy. Garfield also pursued law studies and was admitted to the bar in 1861.

In local politics, James Abram Garfield was nominated for a state senate seat after the death of the previous nominee. He was elected and served from 1860 to 1861. During his time in the state senate, he advocated for Ohio’s first geological survey to assess its mineral resources, though the bill did not pass.

The Civil War Era

A Nation Divided

Following Abraham Lincoln’s election as President, several Southern states seceded from the Union, forming the Confederate States of America. Garfield, deeply invested in the Union’s cause, viewed the conflict as a righteous battle against the institution of slavery. When the Civil War erupted in April 1861 with the attack on Fort Sumter, James Abram Garfield, despite lacking formal military training, felt compelled to serve in the Union Army.

Initially, Garfield deferred his military ambitions at the request of Governor William Dennison to stay in the state legislature, where he helped secure funding for Ohio’s volunteer regiments. During this period, he traveled around northeastern Ohio, rallying support for enlistment. By August 1861, Garfield was commissioned as a colonel in the newly established 42nd Ohio Infantry Regiment, which existed only on paper at the time. His first challenge was to recruit soldiers, a task he accomplished quickly by enlisting many from his own community. After completing their training at Camp Chase near Columbus, James Abram Garfield regiment was deployed to Kentucky.

Early Military Engagements

Assigned by Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell to lead the 18th Brigade, Garfield’s initial task was to expel Confederate forces from eastern Kentucky. His brigade, which included the 42nd Ohio and several other units, embarked on a campaign through the Big Sandy River valley. The operation saw significant action in early January 1862, including a decisive engagement at the Battle of Middle Creek. James Abram Garfield strategic acumen led to a notable victory, and his success in this battle earned him a promotion to brigadier general.

Following this victory, James Abram Garfield issued a proclamation offering amnesty to former Confederates who returned to their homes and pledged loyalty to the Union. This leniency was in stark contrast to his growing belief that the war was a critical fight to end slavery. His forces subsequently pushed remaining Confederate units out of Kentucky.

In early 1862, James Abram Garfield brigade joined Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s army as it advanced on Corinth, Mississippi. Although they arrived after the initial battle, Garfield’s troops played a key role in repelling the Confederate forces during the Battle of Shiloh. Despite being under fire throughout the day, Garfield emerged unscathed. The Union forces eventually took Corinth after the Confederates retreated.

Challenges and Leadership

By summer 1862, Garfield was suffering from jaundice and significant weight loss, necessitating a return home for recovery. During his absence, his political allies worked to secure his nomination for Congress. James Abram Garfield reluctantly accepted, believing his role in the military was crucial, but ultimately chose to follow President Lincoln’s advice to take his congressional seat.

James Abram Garfield congressional career began in December 1863, amid personal grief from the loss of his daughter and an internal conflict about his place in the war. He eventually resigned his military commission to focus on his new role. In Congress, Garfield aligned with the Radical Republicans and became an advocate for more aggressive measures against the South, including the confiscation of rebel-owned lands.

His early congressional efforts were marked by his leadership in reforming the military recruitment process, which he criticized for its abuses. James Abram Garfield was instrumental in passing a conscription bill that eliminated the option to buy out of service.

Political and Legal Life

Under the influence of Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, James Abram Garfield became a strong supporter of a gold-backed dollar and opposed the use of greenbacks. He also endorsed the Wade-Davis Bill, which sought to increase Congressional control over Reconstruction, though Lincoln vetoed it.

Garfield’s relationship with Chase and his political alignments shifted over time, particularly as Chase moved to the Chief Justice role and their interactions diminished. James Abram Garfield post-war period included a brief return to law practice and public speaking. Notably, in the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination, Garfield addressed a crowd on Wall Street to calm public sentiment.

In the years following Lincoln’s death, James Abram Garfield views on the late President evolved, and he came to recognize Lincoln’s profound impact on American history. By the late 1870s, Garfield praised Lincoln as one of the great leaders whose wisdom grew with his power.

The Road to Reconstruction

In 1864, the U.S. Senate passed the 13th Amendment, which aimed to end slavery across the United States. The amendment faced challenges in the House, failing to secure a two-thirds majority until January 31, 1865. It was then sent to the states for ratification. This pivotal moment raised additional questions about African American civil rights. James Abram Garfield questioned the true meaning of freedom, asking if it was merely the absence of chains or something more substantive.

Garfield’s Position on Civil Rights and Reconstruction Efforts

James Abram Garfield was a strong advocate for both abolition and black suffrage. During President Johnson’s administration, he supported Johnson’s initial efforts to rapidly restore Southern states but did so with caution. Garfield’s old friendship with Johnson led him to believe their political differences were minimal. However, Johnson’s veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau bill and other actions soon made Garfield doubt Johnson’s sanity.

Congressional Struggles and Impeachment Proceedings

The 1866 campaign saw Johnson’s contentious relationship with Congress take center stage. James Abram Garfield faced internal Republican opposition but secured his reelection due to Northern support and the South’s disenfranchisement. Initially, Garfield was reluctant to endorse Johnson’s impeachment but supported legislation like the Tenure of Office Act to limit Johnson’s powers. Although he was absent for the impeachment vote, Garfield supported all 11 impeachment articles and was disheartened by Johnson’s acquittal.

Evolving Views and Financial Reforms

By the time Grant took office in 1869, James Abram Garfield had distanced himself from radical Republican elements. He supported the 15th Amendment and the readmission of Georgia as a right, not a political maneuver. However, Garfield’s opposition to the Ku Klux Klan Act highlighted his struggle to balance his criticism of the Klan with concerns about expanding presidential powers.

Economic Policies and Financial Investigations

James Abram Garfield commitment to the gold standard and opposition to paper money were central to his economic policies. Appointed to the House Ways and Means Committee in 1865, he advocated for a return to specie payments over paper currency. Despite his preference for free trade, Garfield’s economic stance led to his removal from the committee. He later chaired the House Appropriations Committee but yearned for a return to Ways and Means.

Investigating Financial Scandals

In January 1870, James Abram Garfield led an investigation into the Black Friday Gold Panic, a scheme involving Jay Gould and James Abram Garfield Fisk to corner the gold market. James Abram Garfield investigation cleared President Grant and his family of wrongdoing, despite rumors and personal resentment from Grant.

Crédit Mobilier Scandal and Salary Grab Controversy

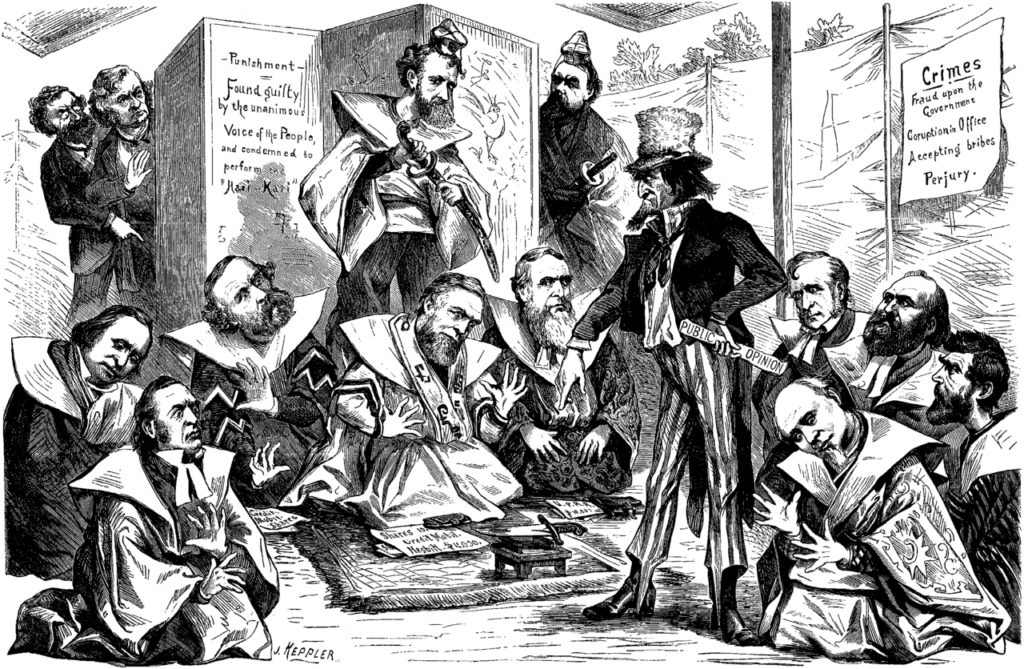

The Crédit Mobilier scandal, involving inflated railroad construction costs, implicated several prominent figures, including Garfield. Though Garfield denied accepting stock, conflicting statements raised questions about his integrity. Additionally, the 1873 “Salary Grab,” which retroactively increased congressional salaries, angered the public and negatively affected Garfield’s reputation despite his refusal to accept the pay raise.

Legislative Leadership and Electoral Commission Role

Following the Democratic takeover of the House in 1875, Garfield lost his chairmanship of the Appropriations Committee but became a key Republican floor leader. He supported civil service reform and opposed monopolistic practices. In the 1876 presidential election dispute, Garfield served on the Electoral Commission, which ultimately declared Rutherford B. Hayes the winner, leading to the end of Reconstruction.

Legal Career and Diverse Interests

James Abram Garfield legal career featured a landmark case, Ex prate Milligan, where he argued that civilians could not be tried by military tribunals while civil courts were operational. His involvement in negotiating the Bitterroot Salish tribe’s relocation and his development of a trapezoid proof of the Pythagorean theorem highlighted his diverse interests and expertise.

Intellectual and Religious Exploration

James Abram Garfield commitment to religious and intellectual exploration, influenced by his experiences and studies, remained a central part of his life. His dedication to freedom of thought and a broader understanding of history reflected his evolving perspectives

The 1880 Presidential Race

Republican Candidacy Dynamics

A satirical illustration from Puck magazine humorously depicted Ulysses S. Grant relinquishing his sword to James Abram Garfield, reflecting the tensions and shifting allegiances of the time. Garfield, freshly elected to the Senate with John Sherman’s backing, was initially a supporter of Sherman for the 1880 Republican nomination. However, some Republicans, notably Wharton Barker from Philadelphia, saw Garfield as a stronger candidate for the nomination. Despite Garfield’s reluctance and denial of interest, this attention fueled Sherman’s suspicions about Garfield’s ambitions. Other key contenders included James G. Blaine, former President Grant, and various emerging candidates.

At this juncture, the Republican Party was deeply divided into two factions: the “Stalwarts,” who endorsed the traditional patronage system, and the “Half-Breeds,” advocating for civil service reform. As the convention commenced, Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York, leading the Stalwarts and supporting Grant, suggested that delegates should pledge allegiance to the eventual nominee in the general election. When three delegates from West Virginia refused, Conkling attempted to expel them, but Garfield intervened passionately, defending their right to withhold judgment. This intervention swayed the crowd and bolstered Garfield’s reputation as a unifying figure.

During the convention, Garfield nominated Sherman but found limited support. Grant led the first ballot with 304 votes, while Blaine garnered 284 and Sherman lagged behind with 93. The subsequent ballots revealed a stalemate between Grant and Blaine, neither achieving the 379 votes required for nomination. In a strategic move, Jeremiah McLain Rusk and Benjamin Harrison shifted support to Garfield, breaking the deadlock. Garfield, initially reluctant, was eventually nominated with 399 votes after former Sherman and Blaine supporters rallied behind him. To appease the Stalwart faction, Chester A. Arthur, a Conkling ally, was chosen as the vice-presidential candidate.

The Election Battle

Campaigning Against Hancock

An election poster for James Abram Garfield and Arthur highlights their campaign. Despite Arthur’s presence on the ticket, lingering factionalism from the convention persisted. Garfield traveled to New York to mend relations and unify the party for the campaign, returning to Ohio to let others handle active campaigning. Meanwhile, the Democrats nominated Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, a career military officer from Pennsylvania. Hancock and the Democrats expected strong support from the South, while the North was anticipated to favor Garfield, leading the campaign to focus on key battleground states like New York and Indiana.

While the differences between the candidates were minimal, Republicans capitalized on the “bloody shirt” tactic, reminding voters of the Democratic Party’s Civil War legacy and its potential to undermine Union veterans and military pensions. However, as time passed since the war, this approach lost its impact. With election day approaching, Republicans shifted focus to the tariff issue, arguing that a Hancock presidency would threaten tariff protections crucial for Northern workers.

Hancock’s misstep, calling the tariff a “local question,” further played into Republican hands, solidifying Garfield’s support. The election was narrowly decided with Garfield winning the popular vote by fewer than 2,000 votes but securing a clear victory in the Electoral College, 214 to 155. Garfield became the only sitting House member elected to the presidency.

Garfield’s Presidency and Key Actions

Cabinet Composition and Early Challenges

In the lead-up to his inauguration, Garfield faced the challenge of forming a cabinet that would bridge the party’s internal divisions. With much support coming from Blaine’s faction, Blaine was appointed Secretary of State. Garfield also nominated William Windom for Treasury Secretary, William H. Hunt for Navy Secretary, Robert Todd Lincoln for War Secretary, and Samuel J. Kirkwood for Interior Secretary. Thomas Lemuel James, a New Yorker, was named Postmaster General, and Wayne Macveighs was appointed Attorney General despite Blaine’s attempts to block him.

Garfield’s inaugural address, while emphasizing African American civil rights and various policy issues, was critiqued as uninspired and formulaic. The speech included a notable condemnation of Mormon polygamy but lacked depth due to its rushed preparation. Garfield’s appointment of James sparked conflict with Conkling, leading to a fierce battle over patronage positions. When Garfield nominated Judge William H. Robertson for Collector of the Port of New York, Conkling tried to invoke senatorial courtesy to block the appointment.

Garfield stood firm, resulting in Conkling and his ally Senator Thomas C. Platt resigning their seats in an attempt to prove their point, but they were met with further humiliation as their seats were filled by others. Robertson’s confirmation marked Garfield’s victory over Conkling, and he proceeded to balance factional interests by appointing several of Conkling’s associates.

Debt Refinancing and Judicial Appointments

Garfield ordered Treasury Secretary Windom to refinance the national debt by calling in high-interest bonds and offering new ones at lower rates, saving taxpayers an estimated $10 million. During his presidency, Garfield also re-nominated Stanley Matthews to the Supreme Court, a nomination that had previously stalled under President Hayes. Matthews was confirmed despite opposition linked to his past prosecution of a newspaper editor who had assisted runaway slaves. Matthews served on the Court until his death in 1889.

Push for Reform

Garfield was sympathetic to civil service reform, believing the spoils system was damaging the presidency. Despite this, some reformers were disappointed when Garfield offered only limited tenure reforms and appointed old friends. Corruption in the Post Office Department, particularly concerning star route contracts, also needed addressing. Garfield took decisive action against postal corruption, demanding the resignation of Assistant Postmaster General Thomas J. Brady and pursuing prosecutions. Although Brady was ultimately acquitted, Garfield’s stance demonstrated his commitment to rooting out corruption, regardless of party connections.

Civil Rights and Education

Garfield’s Vision for African American Rights

James Garfield viewed education as the cornerstone of advancing African American civil rights. He was deeply concerned about the erosion of rights for freedmen, who had gained citizenship and suffrage during Reconstruction but faced significant opposition in the South. Garfield worried that without intervention, African Americans might remain in a state of perpetual disenfranchisement and illiteracy, effectively becoming America’s “permanent peasantry.” To combat this, he proposed a universal education system funded by the federal government.

In February 1866, while serving as a congressman from Ohio, Garfield, alongside Ohio School Commissioner Emerson Edward White, drafted a bill for a National Department of Education. Their aim was to use statistical evidence to convince Congress of the need for a federal agency dedicated to school reform. However, by the time Garfield assumed the presidency, interest in African American rights had waned among Congress and the Northern public, and no federal funding was allocated for universal education during his term.

Despite these setbacks, Garfield made efforts to appoint African Americans to prominent positions, including Frederick Douglass as recorder of deeds in Washington, Robert Elliot as a special agent to the Treasury, John M. Langston as Haitian minister, and Blanche K. Bruce as register to the Treasury. He believed that gaining Southern support for the Republican Party would require focusing on “commercial and industrial” interests rather than race issues, shifting away from Hayes’s policy of conciliating Southern Democrats. To break the Democratic stronghold in the Solid South, Garfield sought advice from Virginia Senator William Mahone of the biracial independent Readjuster Party, aiming to leverage their strength for the Republicans.

Foreign Policy and Naval Reform

Expanding American Influence

Garfield, with limited foreign policy experience, relied heavily on Secretary of State James G. Blaine. Both Garfield and Blaine were committed to promoting freer trade, particularly within the Western Hemisphere, to counterbalance British dominance in the region. They believed that increasing trade with Latin America would boost American prosperity and reduce British influence.

Garfield authorized Blaine to call for a Pan-American conference in 1882 to mediate disputes among Latin American nations and to discuss increasing trade. Additionally, they hoped to negotiate a peace settlement in the ongoing War of the Pacific involving Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. While Blaine favored a resolution that would not alter Peru’s territory, Chile had already occupied Lima by 1881 and was unwilling to return to the previous status quo.

Garfield also aimed to expand American influence globally by renegotiating the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty to allow the United States to build a canal through Panama without British involvement and by reducing British influence in Hawaii. Plans for commercial treaties with Korea and Madagascar were also considered. Although Garfield and Blaine’s ambitious plans for international engagement were cut short by Garfield’s assassination, they made strides in naval reform. The envisioned naval expansion and modernization ultimately led to the construction of the Squadron of Evolution, albeit on a smaller scale than initially planned.

Assassination

The Plot and Its Aftermath

Charles J. Guiteau, a self-styled Stalwart, believed that his support for Garfield’s election entitled him to a federal position. Despite being unqualified and speaking no foreign languages, Guiteau aspired to a consulship in Paris. After being repeatedly denied by Secretary Blaine, Guiteau became convinced that Garfield’s death would restore peace within the Republican Party and secure rewards for fellow Stalwarts, including himself.

Guiteau’s opportunity to act came on July 2, 1881, when James Abram Garfield was scheduled to depart Washington for New Jersey. Concealing himself at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, Guiteau shot Garfield twice as he prepared to leave. Guiteau was quickly apprehended and later expressed his belief that Garfield’s death would benefit the Stalwarts.

Medical Treatment and Death

Garfield’s injuries included a bullet that penetrated his abdomen and shattered a rib. Initially, there was some improvement in his condition, and efforts were made to keep him comfortable using one of the first successful air conditioning units. However, the medical treatment of the time, including the use of unsterilized instruments and probing for the bullet, exacerbated his condition. The failure of a primitive metal detector, invented by Alexander Graham Bell, to locate the bullet further complicated Garfield’s treatment.

James Abram Garfield health deteriorated over the summer, marked by severe infections and a dramatic weight loss. By September 1881, he was moved to Elberon, New Jersey, in a last attempt to improve his condition. Despite some initial hope, James Abram Garfield health continued to decline, and he died on September 19, 1881. His final moments were marked by severe pain and the inability to pick up a glass of water. Chester A. Arthur, the vice president, succeeded Garfield and was sworn in as president the following day.

Guiteau’s Trial and Execution

Guiteau was indicted for James Abram Garfield murder and his trial began in October 1881. He argued that Garfield’s death was due to medical malpractice rather than his actions. Despite his defense’s attempt to use an insanity plea, Guiteau was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed on June 30, 1882, amid a backdrop of intense public and media scrutiny.

Funeral, Memorials, and Commemorations

James A. James Abram Garfield funeral was marked by solemnity and grand tributes. His casket traveled from Long Branch to Washington, D.C., and then to Cleveland for burial. Along the way, tracks were covered with flowers and homes adorned with flags, reflecting the nation’s grief. At the Capitol, over 70,000 people lined up to pay their respects while Garfield’s body lay in state from September 21 to 23, 1881. In Cleveland, more than 150,000 mourners attended the procession, with former Presidents Grant and Hayes, and Generals Sherman, Sheridan, and Hancock among the attendees. Garfield was initially interred in the Schofield family vault until his permanent memorial was completed.

Memorials and Honors

Numerous memorials were established to honor James Abram Garfield memory. In April 1882, a postage stamp was issued in his honor. Sculptor Frank Happer Berger created a monument in San Francisco in 1884, and the James A. Garfield Monument was dedicated in Washington in 1887. A monument in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park followed in 1896. In Victoria, Australia, Cannibal Creek was renamed Garfield in his honor.

James Abram Garfield was permanently interred on May 19, 1890, in a mausoleum at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland. The dedication ceremony was attended by notable figures including Presidents Hayes, Harrison, and McKinley. The monument features panels depicting Garfield as a teacher, general, orator, and includes scenes from his presidency and funeral.

Legacy and Historical View

In the years following James Abram Garfield assassination, his life was celebrated as a symbol of the American dream. However, as the 20th century progressed, public interest in Garfield diminished. Historians note that Garfield’s presidency, while short, had a promising start, and his efforts to reform the political system were significant. Despite this, his legacy has often been overshadowed by more prominent figures of his time.

Historians like Justus D. Doenecke and Bernard A. Weisberger have praised James Abram Garfield contributions and his impact on the presidency. While some view Garfield’s presidency as a “what if,” his work against the spoils system and his influence on the Republican Party are seen as notable achievements.

In recent years, James Abram Garfield contributions and his presidency have received renewed attention. Efforts to preserve and commemorate his legacy continue, reflecting an appreciation for his role in American history.