Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908) stands out in American history as both the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving two non-consecutive terms from 1885 to 1889 and again from 1893 to 1897. His election was historically significant, marking him as the first Democrat to win the presidency following the Civil War. In a period dominated by the Republican Party, which held the presidency from 1869 to 1933, Cleveland’s leadership was a breath of fresh air for many voters seeking change.

Grover Cleveland electoral success is notable; he triumphed in three presidential elections—1884, 1888, and 1892—making him the only U.S. president to serve non-consecutive terms. His unique electoral journey highlights his enduring appeal to the American electorate.

Grover Cleveland as both the 22nd and 24th president of USA (topicsxpress.com)

His political career began when he was elected mayor of Buffalo, New York, in 1881. Cleveland quickly gained a reputation for his honest and straightforward approach, which resonated with the public. This reputation propelled him to the governorship of New York in 1882, where he collaborated closely with Theodore Roosevelt, then the minority leader of the state assembly, to enact meaningful reform measures. Their partnership was instrumental in addressing corruption and inefficiency in state government, drawing national attention and setting a precedent for future political reforms.

As the leader of the Bourbon Democrats, Cleveland championed a pro-business agenda that emphasized limited government intervention. He was a staunch opponent of high tariffs, free silver, inflationary policies, imperialism, and government subsidies for businesses, farmers, or veterans. His advocacy for political reform and fiscal responsibility made him a symbol of the conservative movement during his time. Cleveland was widely respected for his commitment to honesty, self-reliance, integrity, and the principles of classical liberalism, which he practiced throughout his political career. His determined fight against political corruption and patronage garnered him support from many disillusioned Republicans, known as “Mugwumps,” who switched their allegiances to him in the 1884 election.

After narrowly losing to Benjamin Harrison in the 1888 election, Cleveland returned to private life and joined a law firm in New York City. However, his political journey was far from over, as he made a triumphant return to the presidency in the 1892 election. His second term began amid the economic turmoil of the Panic of 1893, which led to a nationwide depression. Many Americans held the Democrats responsible for the economic crisis, paving the way for a Republican resurgence in the 1894 midterm elections and the rise of agrarian and silverite factions within the Democratic Party.

Grover Cleveland presidency was marked by his strong anti-imperialist stance. He opposed the annexation of Hawaii, launching an investigation into the 1893 coup that overthrew Queen Liliʻuokalani and advocating for her restoration to the throne. This position reflected his commitment to fairness and justice, resonating with those who valued sovereignty and the rights of nations.

While Cleveland was an effective policymaker, his presidency was not without its challenges and controversies. His decision to intervene in the Pullman Strike of 1894, aimed at maintaining order and keeping the railroads running, alienated many labor unions and Democrats in Illinois. Additionally, his support for the gold standard and his resistance to the free silver movement frustrated many within the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party. Critics claimed that he lacked imagination and struggled to respond effectively to the economic hardships, strikes, and unrest that characterized his second term. Nonetheless, his reputation for integrity and strong moral character endured, even amid criticism.

Prominent biographer Allan Nevins summed up Grover Cleveland character by stating, “[I]n Grover Cleveland, the greatness lies in typical rather than unusual qualities. He had no endowments that thousands of men do not have. He possessed honesty, courage, firmness, independence, and common sense. But he possessed them to a degree other men do not.” Despite facing unpopularity by the end of his second term—even among fellow Democrats—Cleveland’s legacy as a principled leader remained intact.

After leaving the White House, Cleveland continued to be engaged in public life, serving as a trustee of Princeton University. He remained outspoken about his political views until his health began to decline in 1907, leading to his passing in 1908. Today, Grover Cleveland is celebrated for his unwavering honesty, integrity, and commitment to his principles. His willingness to transcend party lines and his effective leadership have earned him a place among the more respected U.S. presidents, typically ranked in the middle to upper tiers of historical evaluations.

Early Life

Childhood and Family History

Caldwell Presbyterian Parsonage, Birthplace of Grover Cleveland in Caldwell, New Jersey

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born on March 18, 1837, in Caldwell, New Jersey, to Ann (née Neal) and Richard Falley Cleveland. His father, a Congregational and Presbyterian minister, hailed from Connecticut, while his mother came from Baltimore, being the daughter of a local bookseller. Cleveland’s lineage reflects a rich tapestry of heritage, with English ancestors arriving in Massachusetts from Cleveland, England, in 1635. This ancestral connection to England, along with his family’s varied backgrounds, played a significant role in shaping his identity.

Grover Cleveland paternal lineage included notable historical figures, such as his grandfather, Richard Falley Jr., who fought valiantly at the Battle of Bunker Hill and was the son of a Guernsey immigrant. On his maternal side, Cleveland descended from Anglo-Irish Protestants and German Quakers in Philadelphia. Interestingly, he was distantly related to General Moses Cleaveland, the namesake of the city of Cleveland, Ohio, which further underscores the historical significance of his family background.

Cleveland, the fifth of nine siblings, was named Stephen Grover in honor of the first pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Caldwell, where his father served at the time. As he grew older, he became known simply as Grover. In 1841, the Cleveland family relocated to Fayetteville, New York, where Grover spent much of his formative years. Neighbors fondly remembered him as a lively child with a penchant for mischief and a love for outdoor sports.

In 1850, the Cleveland family faced financial challenges, leading Richard to accept a position as the district secretary for the American Home Missionary Society in Clinton, New York. Despite his father’s dedication to missionary work, the family struggled to make ends meet, which forced Grover to leave school and embark on a two-year mercantile apprenticeship in Fayetteville. This experience, while austere, provided him with valuable insights into business and the working world. After completing his apprenticeship, Grover returned to Clinton to continue his education.

However, tragedy struck in 1853 when Richard’s health began to decline due to the demands of his missionary duties. The family moved to Holland Patent, New York, and shortly after, Richard Cleveland passed away from a gastric ulcer. Grover learned of his father’s death through a newspaper boy, a moment that deeply affected him.

Education and Moving West

An Early, Undated Photograph of Grover Cleveland

Grover Cleveland educational journey began at the Fayetteville Academy and the Clinton Grammar School, although it was interrupted by the need to support his family following his father’s death. In 1854, his brother William secured a teaching position at the New York Institute for the Blind in New York City, where he arranged for Grover to work as an assistant teacher. By the end of 1854, Grover returned home to Holland Patent, where an elder from his church offered to fund his college education on the condition that he promised to become a minister. Grover declined the offer, expressing a desire to forge his own path, and in 1855, he decided to head west.

His journey first took him to Buffalo, New York, where his uncle-in-law, Lewis F. Allen, provided him with a clerical job. Allen was a prominent figure in Buffalo, introducing Grover to influential individuals, including partners at the law firm of Rogers, Bowen, and Rogers, where Millard Fillmore, the 13th president of the United States, had once worked. Cleveland eventually secured a clerkship with the firm, immersing himself in legal studies. By 1859, he successfully passed the bar exam and was admitted to the New York bar.

Early Career and the Civil War

Cleveland spent three years with the Rogers firm before establishing his own legal practice in 1862. In January 1863, he was appointed assistant district attorney of Erie County. With the American Civil War in full swing, Congress enacted the Conscription Act of 1863, mandating military service for able-bodied men unless they could hire a substitute. Cleveland chose to pay $150—a sum equivalent to about $3,712 today—to a Polish immigrant named George Benninsky to serve in his place. Benninsky would survive the war, a decision that highlighted Cleveland’s pragmatic approach to the pressing challenges of his time.

As a lawyer, Grover Cleveland earned a reputation for his intense focus and unwavering dedication to his work. In 1866, he took on a pro bono case, defending individuals involved in the Fenian raid, which showcased his commitment to justice. In 1868, he gained further recognition for successfully defending a libel suit against the editor of Buffalo’s Commercial Advertiser, solidifying his status in the legal community.

Throughout this period, Cleveland maintained a lifestyle of simplicity, residing in a modest boarding house and dedicating his earnings to support his mother and younger sisters. While his living conditions were austere, he actively engaged in social life, often enjoying the camaraderie found in hotel lobbies and saloons. He consciously distanced himself from the higher social circles of Buffalo, focusing instead on building his career and supporting his family.

Political career in New York

Sheriff of Erie County

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born on March 18, 1837, in Caldwell, New Jersey, to Ann and Richard Falley Cleveland. The family background played a significant role in shaping Cleveland’s values and character. His father, a Congregational and Presbyterian minister from Connecticut, was known for his strong moral principles, which influenced Grover from a young age. His mother, Ann, originally from Baltimore, was the daughter of a bookseller, instilling in Cleveland a love for learning and literature. He was the fifth of nine children, which fostered a sense of responsibility and resilience in him, traits that would later define his political career.

Cleveland’s early childhood was filled with outdoor adventures in Fayetteville, New York, where the family moved in 1841. However, the loss of his father in 1853 forced Cleveland to leave school and support his family. At just 16, he took on the role of assistant teacher and worked hard to ensure his siblings could continue their education. Although he received an offer from a church elder to finance his college education, he declined, feeling uncalled to the ministry. Instead, in 1855, he moved to Buffalo, New York, where he worked in a clerical position for his uncle-in-law, which allowed him to pursue a legal education.

Early Career and Civil War Involvement

Cleveland began studying law while working as a clerk and quickly established a reputation as a competent attorney. In 1863, he became the assistant district attorney of Erie County, a position that provided him with valuable legal experience. During this time, he avoided military service during the Civil War by hiring a substitute—a common practice for those who could afford it. While some criticized this decision, it allowed him to focus on his burgeoning legal career.

As a lawyer, Cleveland gained recognition for his dedication and skill. He took on high-profile cases, including a notable libel suit where he successfully defended a client. His commitment to his work and his family’s well-being helped him establish himself in Buffalo’s legal community, despite living a modest lifestyle.

Political Career in New York

Cleveland’s political career began to take shape as he aligned himself with the Democratic Party. He had a notable aversion to Republicans, particularly John Fremont and Abraham Lincoln. In 1865, he ran for the position of District Attorney but lost narrowly to his friend and roommate, Lyman K. Bass, the Republican nominee. This setback did not deter him, and in 1870, with the encouragement of his friend Oscar Folsom, Cleveland secured the Democratic nomination for sheriff of Erie County, New York. He won the election by a narrow margin of just 303 votes, taking office on January 1, 1871, at the age of 33.

Cleveland’s time as sheriff was not without its challenges. His tenure was marked by a notable incident on September 6, 1872, when he executed a convicted murderer named Patrick Morrissey. Despite his personal reservations about capital punishment, Cleveland carried out the execution himself, a decision that haunted him later. Although Cleveland’s service in this role was generally considered unremarkable, it did provide him with a financial boost; the sheriff’s fees during his two-year term amounted to about $40,000, a significant sum equivalent to over $1 million today.

After his term ended, Cleveland returned to his law practice, partnering with friends Lyman K. Bass and Wilson S. Bissell. Although Bass was later replaced by George J. Sicard due to his election to Congress, Cleveland and Bissell quickly rose to prominence in Buffalo’s legal community. At this point, Cleveland’s political career was relatively unremarkable, with biographers noting that few could have predicted he would soon ascend to the presidency.

Mayor of Buffalo

In the 1870s, Buffalo’s municipal government was plagued by corruption, with both Democratic and Republican political machines collaborating to divide the spoils of office. In 1881, the Republicans nominated a slate of particularly disreputable candidates, presenting an opportunity for the Democrats to capture disaffected Republican voters. Cleveland was approached to run for Mayor of Buffalo, contingent on the Democratic Party’s slate meeting his standards. Recognizing the chance to make a meaningful impact, he accepted the nomination after ensuring more notorious politicians were left off the ticket.

Cleveland was elected mayor in November 1881, receiving 15,120 votes against Republican opponent Milton Earl Beebe’s 11,528. He took office on January 2, 1882, and quickly set about tackling the entrenched interests within the party machines. Among his significant actions was the veto of a street-cleaning bill that favored a politically connected bidder, despite the contract being the subject of competitive bidding. His veto message was strong, asserting that the contract was a “bare-faced, impudent, and shameless scheme to betray the interests of the people.” This decisive stand resonated with the public and led to the contract being awarded to the lowest bidder instead.

Cleveland also advocated for the creation of a Commission to improve Buffalo’s sewer system at a significantly lower cost than previously proposed. His successful efforts to safeguard public funds and promote government accountability earned him a reputation as a principled leader willing to fight against corruption.

Governor of New York

As Grover Cleveland reputation for reform grew, Democratic party officials began to consider him a viable candidate for governor. In 1882, amid a split in the Republican party, he emerged as the compromise candidate for the Democrats after a contentious convention. Cleveland won the election decisively, receiving 535,318 votes to Republican Charles J. Folger’s 342,464—a record margin at the time. His victory not only solidified his position in New York politics but also marked a significant shift in the state’s political landscape.

Upon taking office, Cleveland wasted no time in asserting his commitment to fiscal responsibility. In his first two months, he issued eight vetoes, including one on a popular bill to reduce fares on New York City elevated trains, arguing that it would violate the Contract Clause of the Constitution. While his stance initially drew criticism, it ultimately garnered widespread support, reinforcing his reputation as a principled leader willing to challenge the status quo.

Grover Cleveland staunch opposition to political corruption alienated him from the powerful Tammany Hall organization and its boss, John Kelly. However, his unwavering commitment to reform attracted support from reform-minded Republicans, including Theodore Roosevelt, enabling him to pass significant laws aimed at improving municipal governance. This collaboration earned Cleveland national recognition as a reformer, setting the stage for his future political ambitions.

Election of 1884: A Turning Point in American Politics

The 1884 United States presidential election was a significant event that marked a turning point in American politics. It showcased a clash between two contrasting figures: the Republican nominee, James G. Blaine, and the Democratic nominee, Grover Cleveland. This election not only highlighted the intense political rivalry of the time but also underscored the issues of corruption and reform that were prevalent in American society.

Nomination for President: A Divided Republican Party

The Republican Party convened its national convention in Chicago in June 1884. The party chose James G. Blaine, a former U.S. House Speaker from Maine, as their presidential candidate. Blaine’s nomination was met with substantial discontent among certain factions within the Republican Party, particularly the “Mugwumps,” who viewed him as corrupt and self-serving. His candidacy was further compromised by a lack of support from key party leaders, including the Conkling faction and President Chester Arthur. This discord within the Republican ranks opened the door for the Democrats, who were eager to capitalize on the Republicans’ internal strife.

Initially, Samuel J. Tilden, who had previously run for president in the disputed election of 1876, was the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination. However, after declining due to health issues, support shifted to other candidates, including Grover Cleveland, Thomas F. Bayard, Allen G. Thurman, and Benjamin Butler. Each of these candidates faced significant hurdles: Bayard’s past support for secession alienated Northern Democrats, while Butler’s reputation in the South was tarnished by his wartime actions. Grover Cleveland, though not without detractors, emerged as a leading candidate. He secured the nomination with considerable support from delegates, ultimately choosing Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana as his running mate.

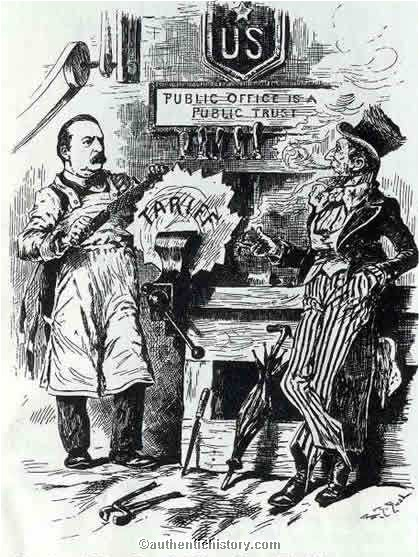

Cleveland’s Campaign: Fighting Corruption

Corruption emerged as the central theme of the 1884 election. Throughout his political career, Blaine had been embroiled in numerous scandals, which tarnished his reputation. Cleveland’s image as a reformer and an opponent of corruption became the Democrats’ strongest asset. Reform-minded Republicans, known as Mugwumps, rallied behind Cleveland, viewing him as a figure who could bring integrity back to government. The slogan “A public office is a public trust,” crafted by William C. Hudson, encapsulated Cleveland’s reformist message.

As the campaign progressed, both sides engaged in fierce attacks against one another. Cleveland’s supporters revived allegations of Blaine’s corrupt dealings with railroads, specifically focusing on his involvement with the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad and the Union Pacific Railway. This time, damaging correspondence was uncovered that made Blaine’s earlier denials appear less credible. One particularly incriminating letter, where Blaine requested to “Burn this letter,” became fodder for the Democrats’ campaign slogan, tauntingly stating, “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the state of Maine, ‘Burn this letter!'”

On the other side, the Republicans attempted to undermine Cleveland by exposing a scandal from his past. They alleged that he had fathered an illegitimate child, leading to the infamous rallying cry, “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa?” Cleveland confronted the allegations head-on, instructing his supporters to remain truthful and acknowledging his responsibility in the matter. He openly admitted to paying child support to Maria Crofts Halpin, the mother of his alleged child, asserting that he had acted honorably.

Election Results: A Narrow Victory for Cleveland

The outcome of the 1884 election hinged on the swing states of New York, New Jersey, Indiana, and Connecticut. Blaine sought to garner support from Irish Americans, hoping to capitalize on his heritage and prior support for the Irish National Land League. However, a speech by Republican Samuel D. Burchard, which labeled the Democrats as the party of “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion,” backfired. The Democrats effectively used this implied anti-Catholic sentiment to galvanize support among Irish voters.

In the end, Cleveland secured a narrow victory, winning New York by just 1,200 votes and the popular vote by a mere quarter of a percent. The electoral count stood at 219 votes for Cleveland to 182 for Blaine. Following his victory, the Democrats playfully retorted to the “Ma, Ma…” chant with, “Gone to the White House. Ha! Ha! Ha!”

First Presidency (1885–1889): A Commitment to Reform

As Grover Cleveland took office, he faced the daunting task of appointing individuals to various government positions. Departing from the spoils system, he pledged to retain competent Republicans and only appoint Democrats based on merit. His early administration focused on reducing the federal workforce, recognizing that many departments were bloated with unnecessary positions.

Grover Cleveland also championed significant reforms, including the establishment of the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1887, which aimed to regulate the railroad industry. His administration confronted issues surrounding land grants given to railroads, resulting in the forfeiture of approximately 81 million acres due to the railroads’ failure to meet their obligations. This bold move angered railroad investors but demonstrated Cleveland’s commitment to the public good.

One of the notable aspects of Grover Cleveland presidency was his extensive use of the veto power. He vetoed hundreds of private pension bills, asserting that Congress should not override the decisions of the Pension Bureau. His most famous veto came in 1887 with the Texas Seed Bill, where he rejected a request for federal assistance to farmers affected by drought. In his veto message, he emphasized his belief in limited government, arguing that the federal government should not support individual suffering unrelated to public service.

Economic Issues: Currency, Tariffs, and Reform

Grover Cleveland presidency was marked by significant debates over economic policies, particularly regarding currency and tariffs. The contentious issue of whether to back currency with gold or silver divided political factions. Cleveland and his Treasury Secretary, Daniel Manning, firmly supported the gold standard, opposing the free coinage of silver, which many Western Democrats and Republicans advocated.

Tariffs were another focal point during Grover Cleveland administration. While not a primary campaign issue, he believed in reducing tariffs, which had been elevated during the Civil War and had since resulted in government surpluses. In 1886, a bill to reduce tariffs narrowly failed in the House, illustrating the contentiousness of the debate.

Overall, the 1884 election and Cleveland’s first presidency set the stage for ongoing discussions about reform, corruption, and the role of government in American society. Cleveland’s commitment to integrity and his significant policy initiatives left a lasting impact on the Democratic Party and American politics as a whole.

Foreign Policy (1885–1889)

Grover Cleveland, a staunch non-interventionist, campaigned against imperialism and expansion. He dismissed the Nicaragua canal treaty promoted by the previous administration and sought to limit U.S. involvement abroad. His Secretary of State, Thomas F. Bayard, engaged in discussions with the UK’s Joseph Chamberlain regarding fishing rights, taking a conciliatory approach despite resistance from New England’s Republican Senators. Cleveland also withdrew the Berlin Conference treaty aimed at securing an open door for U.S. interests in the Congo.

Military Policy (1885–1889)

Grover Cleveland military strategy focused on modernization and self-defense. In 1885, he established the Board of Fortifications under Secretary of War William C. Endicott to recommend enhancements to U.S. coastal defenses, as none had been made since the late 1870s. The Board proposed a $127 million construction initiative for 29 harbors and river estuaries, advocating for advanced artillery and naval minefields. Most recommendations were enacted, leading to the establishment of over 70 forts by 1910. In the Navy, Cleveland’s administration, led by Secretary of the Navy William Collins Whitney, pushed for modernization, ordering 16 steel-hulled warships by the end of 1888. These ships were crucial during the Spanish-American War and World War I.

Civil Rights and Immigration

Cleveland’s tenure saw minimal progress for African American civil rights. Viewing Reconstruction as a failure, he hesitated to enforce the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed voting rights for African Americans. While he did not appoint black individuals to patronage positions, he allowed Frederick Douglass to continue as recorder of deeds and later appointed James Campbell Matthews, a black former judge, to succeed Douglass. Cleveland expressed disapproval of the injustices faced by Chinese immigrants but believed they resisted assimilation. His administration extended the Chinese Exclusion Act and pushed for the Scott Act, which prohibited the return of Chinese immigrants to the U.S.

Native American Policy

Cleveland regarded Native Americans as wards of the state and advocated for their cultural assimilation. He signed the Dawes Act, which aimed to distribute tribal lands to individual members, but this move faced opposition from many Native Americans. Grover Cleveland believed the Act would alleviate poverty among Native Americans, but it ultimately undermined tribal governments and facilitated the sale of their lands. He also rescinded an executive order by President Arthur that opened Indian lands to white settlement, reinforcing treaty obligations by dispatching Army troops for enforcement.

Marriage and Children

Cleveland was a bachelor when he assumed the presidency at 47, with his sister Rose serving as hostess. In 1885, he began corresponding with Frances Folsom, the daughter of a deceased friend. They married in the White House on June 2, 1886, making Cleveland the only president to marry in office. The couple had five children: Ruth, Esther, Marion, Richard, and Francis. Tragically, their daughter Ruth died of diphtheria in 1904. Cleveland also acknowledged paternity of a child, Oscar Folsom Cleveland, born in 1874 to Maria Crofts Halpin.

Administration and Cabinet

Grover Cleveland Cabinet included notable figures like Thomas F. Bayard (Secretary of State), Daniel Manning (Secretary of the Treasury), and William Crowninshield Endicott (Secretary of War). During his first term, he successfully nominated two justices to the Supreme Court: Lucius Q. Lamar and Melville Fuller. Additionally, he appointed 41 lower federal court judges, including two to the circuit courts and 30 to district courts.

Election of 1888 and Return to Private Life (1889–1893)

In the 1888 presidential election, Grover Cleveland faced off against the Republican nominee, Benjamin Harrison, a former U.S. Senator from Indiana, with Levi P. Morton as his running mate. Cleveland was renominated by the Democrats at their convention in St. Louis, with Allen G. Thurman of Ohio stepping in as his new vice-presidential candidate following the death of Thomas A. Hendricks in 1885.

The Republicans gained a strategic advantage during the campaign, largely due to Cleveland’s poorly managed efforts, overseen by Calvin S. Brice and William H. Barnum. In contrast, Harrison’s team employed more aggressive fundraising tactics, enlisting the help of influential figures like Matt Quay and John Wanamaker.

Key to the Republican campaign was the tariff issue, which galvanized protectionist voters in critical industrial states in the North. Additionally, internal divisions within the New York Democratic Party, particularly over David B. Hill’s gubernatorial candidacy, undermined Cleveland’s support in this pivotal swing state. A scandal arose when a letter from the British ambassador endorsing Cleveland became public, further costing him votes in New York.

As in the previous election of 1884, the race centered around swing states like New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Indiana. However, unlike in 1884 when Grover Cleveland triumphed in all four states, he managed to win only two in 1888, losing his home state of New York by a narrow margin of 14,373 votes. Although he secured a plurality of the popular vote with 48.6% against Harrison’s 47.8%, Cleveland lost the Electoral College decisively, with Harrison taking 233 votes to Cleveland’s 168. Fraudulent voting practices known as Blocks of Five helped the Republicans secure Indiana. Despite the loss, Cleveland remained committed to his duties until the end of his term and began contemplating his return to private life.

Private Citizen for Four Years

As Frances Grover Cleveland exited the White House, she expressed her desire to return to find everything as it was, indicating their belief in a return to power in four years. The couple moved to New York City, where Cleveland joined the law firm Bangs, Stetson, Tracy, and Macveigh. While this arrangement was more about sharing office space, it provided a moderate income for Cleveland, who often spent time fishing at their vacation home, Gray Gables, at Buzzard Bay. Their time in New York was marked by the birth of their first child, Ruth, in 1891.

During this period, the Harrison administration pursued several contentious policies, including the McKinley Tariff, which was heavily protectionist, and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which increased the money supply backed by silver. Grover Cleveland publicly condemned these measures, believing they threatened the nation’s financial stability. Initially refraining from criticism, he eventually felt compelled to speak out, penning an open letter to a gathering of reformers in New York in 1891. This “silver letter” thrust Cleveland back into the political spotlight just as the 1892 election approached.

Election of 1892

As Grover Cleveland reputation as a former chief executive solidified and his stance on monetary issues garnered attention, he emerged as a leading candidate for the Democratic nomination. His primary opponent was David B. Hill, a New York Senator who united various anti-Cleveland factions, including silverites and protectionists. However, Hill failed to form a coalition substantial enough to block Cleveland’s nomination, which occurred on the first ballot at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

For vice president, the Democrats chose Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois, a silverite, to balance the ticket against Cleveland’s hard-money stance. Although Cleveland’s faction preferred Isaac P. Gray of Indiana, they ultimately accepted Stevenson, a supporter of greenbacks and free silver aimed at easing rural economic distress.

In the 1892 election, Harrison was re-nominated, leading to a rematch. This election was notably less turbulent than previous contests, with Harrison refraining from campaigning due to the death of his wife, Caroline, from tuberculosis just weeks before Election Day. As a mark of respect, all candidates, including Cleveland, paused their campaigning.

By 1892, changing attitudes toward tariffs worked against the Republicans; many voters sought reform after the costly measures implemented in Harrison’s administration. Western voters, traditionally Republican, began supporting James B. Weaver of the new Populist Party, who advocated for free silver, generous veterans’ pensions, and an eight-hour workday. The Tammany Hall Democrats remained aligned with the national ticket, enabling a united Democratic front to win New York.

In the end, Grover Cleveland triumphed with significant margins in both the popular and electoral votes, marking his third consecutive plurality in the popular vote.

Second Presidency of Grover Cleveland (1893–1897)

Economic Panic and the Silver Issue

Shortly after Grover Cleveland began his second term, the Panic of 1893 struck the stock market, plunging the nation into economic depression. This crisis was exacerbated by a severe gold shortage linked to the increased coinage of silver. In response, Grover Cleveland summoned Congress for a special session to address the financial turmoil. The debate surrounding the coinage was intense, with many moderates shifting towards repealing the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. Despite strong opposition, silver supporters held a convention in Chicago, and after a prolonged 15-week debate, the House passed the repeal.

In the Senate, the repeal faced significant contention. Cleveland, despite his reservations, lobbied Congress, securing enough Democratic and Eastern Republican votes for a narrow victory in favor of repeal. Although the depletion of the Treasury’s gold reserves continued, subsequent bond issues helped replenish the gold supply. The repeal marked the beginning of the decline of silver as a foundation for American currency.

Tariff Reform

Grover Cleveland next target was the McKinley Tariff. The Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act, introduced by Representative William L. Wilson in December 1893, proposed moderate reductions, particularly on raw materials. To offset revenue loss, it included a two percent income tax on earnings exceeding $4,000.

The Senate, however, imposed over 600 amendments, diluting the proposed reforms. The Sugar Trust, in particular, influenced changes that favored its interests. Outraged by the bill’s final version, Cleveland denounced it as a disgraceful product of corporate control but ultimately allowed it to become law without his signature, believing it was still an improvement over the previous tariff.

Voting Rights

During his second term, Grover Cleveland also opposed the Lodge Bill, which aimed to bolster voting rights by appointing federal supervisors for congressional elections. The Enforcement Act of 1871 had previously established federal oversight of elections. However, Cleveland successfully facilitated the repeal of this law in 1894, shifting the focus from protecting voting rights to their dismantling. This led to further unsuccessful attempts to safeguard voting rights in the following years.

Labor Unrest

The Panic of 1893 severely affected labor conditions nationwide, exacerbating tensions among workers. A group known as Coxey’s Army, led by Jacob S. Coxey, marched to Washington, D.C., advocating for a national road program and a more flexible currency. Though their numbers dwindled by the time they reached the capital, the march highlighted growing dissatisfaction with Cleveland’s policies.

The Pullman Strike had a more significant impact than Coxey’s Army. Sparked by wage cuts and long working hours at the Pullman Company, it escalated into a national crisis. By June 1894, 125,000 railroad workers were on strike, disrupting commerce. Cleveland believed a federal intervention was necessary, leading him to obtain an injunction and dispatch federal troops to Chicago. This decision, while backed by most governors and praised by the press, alienated organized labor from his administration.

As the 1894 elections approached, Grover Cleveland received warnings about impending political fallout due to popular discontent with perceived Democratic incompetence. The elections resulted in a substantial Republican victory, leading to increased opposition control in various states, including Illinois and Michigan.

Foreign Policy (1893–1897)

Grover Cleveland second term also confronted challenges in foreign policy, notably the annexation of Hawaii. When he took office, the situation in Hawaii had evolved, with local businessmen overthrowing Queen Liliuokalani and seeking annexation. Cleveland, who had previously supported free trade with Hawaii, withdrew the annexation treaty from the Senate and dispatched an investigator to assess the situation.

Upon receiving a report that opposed annexation and criticized U.S. involvement in the coup, Cleveland, a staunch anti-imperialist, called for the queen’s restoration. However, negotiations stalled, and Cleveland ultimately recognized the new Republic of Hawaii, which was established under President Dole.

Closer to home, Grover Cleveland upheld an expansive interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, asserting American interests in disputes within the hemisphere. During the Venezuela crisis, he stood with Venezuela against British territorial claims, demanding arbitration. The eventual resolution strengthened relations with both Latin America and Britain, encouraging a broader acceptance of arbitration for international disputes.

Military Policy (1893–1897)

Grover Cleveland administration continued to emphasize military modernization, ordering new naval ships and fortifications while adopting the Krag–Jørgensen rifle as the Army’s primary weapon. The administration expanded the navy, laying the groundwork for a more formidable maritime force, although many of these ships were not completed until after his presidency.

Health Issues

Amidst these political struggles, Grover Cleveland faced serious health concerns. In 1893, he consulted his doctor about a sore spot in his mouth, which led to the discovery of oral cancer. This personal health crisis remained largely undisclosed to the public, as Cleveland underwent surgery to remove the tumor while keeping his condition secret from the nation. His battle with cancer highlighted the challenges he faced both personally and politically during his second term.

Election and Retirement (1897–1908)

Cleveland in 1904

During Grover Cleveland’s second term, his agrarian and silverite adversaries gained control of state Democratic parties, leading to a marginalization of his pro-gold stance, particularly outside urban areas in traditionally Democratic states like Arkansas. In 1896, they seized control of the national Democratic Party, repudiating Cleveland’s administration and the gold standard while nominating William Jennings Bryan on a free-silver platform. Cleveland supported the Gold Democrats’ third-party ticket, which aimed to uphold the gold standard, limit government, and oppose high tariffs, but he chose not to seek a third term.

Ultimately, this ticket garnered only 100,000 votes in the general election, with William McKinley, the Republican nominee, easily defeating Bryan. Bryan was again nominated in 1900, but in 1904, Grover Cleveland conservative allies regained control of the Democratic Party and nominated Alton B. Parker.

After leaving the presidency on March 4, 1897, Cleveland retired to his estate, Westland Mansion, in Princeton, New Jersey. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1897 and served as a trustee of Princeton University, where he supported plans for the Graduate School proposed by Dean Andrew Fleming West over those suggested by Woodrow Wilson, the university’s president at the time. Though financially unable to accept the chairmanship of the commission handling the Coal Strike of 1902, Cleveland occasionally consulted with President Theodore Roosevelt.

He continued to express his opinions on political matters, notably writing an article in The Ladies Home Journal in 1905 where he commented on women’s suffrage, asserting that “sensible and responsible women do not want to vote” and that gender roles were preordained.

In 1906, a faction of New Jersey Democrats promoted Cleveland as a potential candidate for the United States Senate, believing that he could attract votes from disillusioned Republican legislators due to his reputation for statesmanship and conservatism.

Death

Grover Cleveland health had been deteriorating for several years, and in autumn 1907, he became seriously ill. He suffered a heart attack in 1908 and passed away on June 24 at the age of 71 in his Princeton residence. His last words were, “I have tried so hard to do right,” and he was laid to rest at Princeton Cemetery of the Nassau Presbyterian Church.

Honors and Memorials

Grover Cleveland sought a summer retreat during his first term to escape the heat of Washington, D.C. In 1886, he discreetly purchased and remodeled a farmhouse, Oak View, into a summer estate. After losing his re-election bid in 1888, he sold the property, which subsequently became known as Oak View and later Cleveland Heights and Cleveland Park due to suburban development. The Grover Cleveland are commemorated in local murals.

Numerous institutions and locations honor Cleveland, including Grover Cleveland Hall at Buffalo State College and Grover Cleveland Middle School in Caldwell, New Jersey. The town of Cleveland, Mississippi, and Mount Cleveland in Alaska are also named after him. Cleveland became the first U.S. president to be filmed in 1895.

In 1923, he was honored with a postage stamp, followed by further depictions in stamp issues in 1938 and 1986. His portrait appeared on the U.S. $1,000 bill in the 1928 and 1934 series and on the first few $20 Federal Reserve Notes from 1914. As both the 22nd and 24th president, he was featured on two separate dollar coins released in 2012. In 2013, he was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.