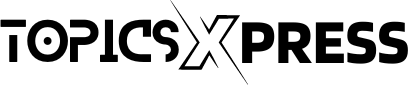

William McKinley, born on January 29, 1843, in Niles, Ohio, served as the 25th president of the United States from 1897 until his untimely assassination in 1901. His presidency marked a critical period in American history, as he led the country through significant economic recovery and territorial expansion. William McKinley was a dedicated member of the Republican Party, and his policies helped shape the party’s dominance in the industrial states and across the nation for decades to come.

One of William McKinley most remarkable achievements was his leadership during the Spanish-American War in 1898. This war not only secured America’s victory over Spain but also brought key territories like Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines under U.S. control. Additionally, Hawaii was annexed during McKinley’s presidency, reflecting America’s growing influence on the global stage. His foreign policies laid the groundwork for the United States to emerge as a world power, and his decisions had long-lasting impacts on America’s future.

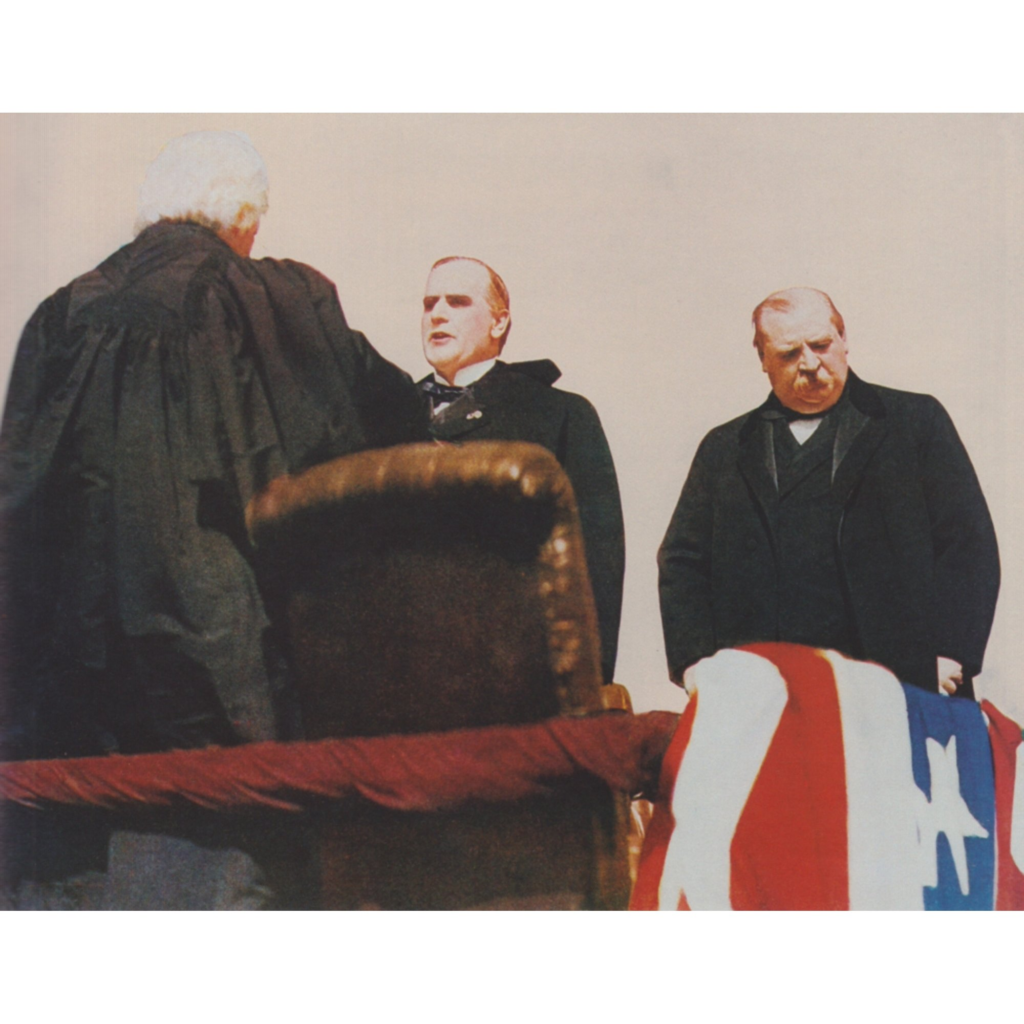

William McKinley 25th President of the United States (topicsxpress.com)

Before becoming president, William McKinley had a distinguished career in public service. He was the last U.S. president who had served in the Civil War, beginning his military career as an enlisted soldier and eventually rising to the rank of brevet major. After the war, McKinley returned to Ohio, where he pursued a legal career and married Ida Saxton. His political journey began when he was elected to Congress in 1876, where he became known as an expert on tariff policies, advocating for protective tariffs that he believed would boost American industries and ensure prosperity.

William McKinley political rise continued when he was elected as governor of Ohio in 1891 and 1893, where he navigated between capital and labor interests. In 1896, amid a deep economic depression, McKinley ran for president, advocating for “sound money” by supporting the gold standard and promising that high tariffs would restore economic prosperity. His victory in the 1896 election is often seen as a turning point, marking the end of the post-Civil War political stalemate and ushering in the Republican-dominated Fourth Party System.

During his presidency, William McKinley oversaw rapid economic growth, and his administration passed the 1897 Dingley Tariff to protect U.S. manufacturers from foreign competition. He also secured the Gold Standard Act in 1900, further stabilizing the national economy. McKinley’s efforts to negotiate peace with Spain ultimately failed, leading to the Spanish-American War, which ended in a swift U.S. victory. The peace treaty that followed granted the U.S. control of key territories and signaled the country’s emergence as a colonial power.

William McKinley was re-elected in 1900, but his second term was tragically cut short when he was assassinated by an anarchist, Leon Ciolkosz, in September 1901. He was succeeded by his vice president, Theodore Roosevelt. Although McKinley’s legacy is often overshadowed by Roosevelt, he is remembered as a president who played a pivotal role in expanding America’s global influence and ensuring economic stability at home.

Early Life and Family Background of William McKinley

William McKinley Jr., born on January 29, 1843, in Niles, Ohio, was the seventh of nine children in a large family of English and Scots Irish descent. His parents, William McKinley Sr. and Nancy (née Allison) McKinley had deep roots in America’s early history. The McKinley family’s ancestry traces back to David McKinley, an immigrant from Derock, County Antrim in present-day Northern Ireland, who settled in Pennsylvania in the 18th century. William McKinley Sr., born in Pine Township, Mercer County, Pennsylvania, followed the family tradition of working in the iron industry.

The William McKinley later moved to Ohio, settling in New Lisbon (now Lisbon), where William Sr. met and married Nancy Allison. Nancy’s family, like the McKinley’s, had early American roots, primarily of English descent. William Sr. operated iron foundries across Ohio in towns like Niles, Poland, and finally Canton. Their household was deeply influenced by the Methodist faith and staunch abolitionist beliefs, common in Ohio’s Western Reserve. These values shaped young McKinley’s upbringing and religious devotion.

At age 16, William McKinley became actively involved in the local Methodist church, and his faith remained a central part of his life. Seeking better educational opportunities for their children, the McKinley family moved to Poland, Ohio, in 1852. McKinley attended Poland Seminary and graduated in 1859 before enrolling at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania. Though he studied there for a year, health and financial issues forced him to return home, and he briefly worked as a postal clerk and teacher. Despite these setbacks, McKinley’s early education and values laid the foundation for his later success.

Civil War Experience: Western Virginia and the Battle of Antietam

Rutherford B. Hayes played a significant role as a mentor to William McKinley, both during and after the Civil War. When the war broke out in 1861, McKinley and his cousin, William McKinley Osbourne, were among the thousands of Ohio men who enlisted for service. They joined the Poland Guards as privates and later became part of the 23rd Ohio Infantry, a newly formed regiment.

The men of the 23rd Ohio were initially frustrated by their inability to elect their officers, as Ohio Governor William Dennison appointed the leadership instead. Under the command of Colonel William Rosecrans, they began training near Columbus. William McKinley quickly adapted to military life, often writing to his hometown newspaper about the Union cause. A bond began to form between McKinley and Major Rutherford B. Hayes, whose leadership impressed McKinley as he helped resolve issues regarding supplies.

In July 1861, William McKinley regiment, now led by Colonel Eliakim P. Scammon, was deployed to western Virginia, where they engaged Confederate forces at Carnifex Ferry. McKinley’s growing responsibility saw him assigned to the brigade quartermaster office by September. After spending a harsh winter near Fayetteville, he was promoted to commissary sergeant in April 1862.

Later that year, the 23rd Ohio joined the Army of the Potomac, participating in key battles such as South Mountain and the bloody Battle of Antietam. William McKinley regiment faced heavy fire, but his bravery in delivering rations to the front line did not go unnoticed. Although the regiment suffered severe casualties, the Union forces triumphed, forcing the Confederates to retreat.

Shenandoah Valley and Promotion

During the winter of 1862–1863, William McKinley’s regiment was stationed near Charleston, Virginia (now West Virginia). He was then ordered back to Ohio to help recruit fresh troops. Upon returning, Governor David Tod surprised McKinley with a commission as second lieutenant in recognition of his service at the Battle of Antietam.

In July 1863, William McKinley and his division skirmished with Confederate cavalry during John Hunt Morgan’s raid at the Battle of Buffington Island. The following year, the command structure in West Virginia was reorganized under General George Crook. McKinley’s division marched into southwestern Virginia to destroy Confederate resources, engaging in the fierce Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain on May 9, where he described the combat as “as desperate as any witnessed during the war.” Following this victory, the Union forces successfully targeted enemy supplies.

As hostilities resumed, William McKinley and his regiment moved into the Shenandoah Valley. Under Major General David Hunter, they captured Lexington, Virginia, in June 1864, but retreated when faced with a strong Confederate presence in Lynchburg. In July, they encountered Confederate General Jubal Early’s forces at Kernstown. Despite the defeat, McKinley was promoted to captain and transferred to General Crook’s staff.

As the war progressed, William McKinley participated in significant engagements, including battles at Berryville, Opequon Creek, and Fisher’s Hill. During the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, he helped rally the troops after an initial setback, turning the tide for the Union.

After the war, William McKinley was brevetted as a major and chose not to continue in the peacetime army, returning to Ohio. He later co-authored the Official Roster of the Soldiers of the State of Ohio in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1866, highlighting his commitment to preserving history.

Legal Career and Marriage

After the Civil War ended in 1865, William McKinley decided to pursue a career in law. He began his studies in the office of an attorney in Poland, Ohio, and the following year attended Albany Law School in New York. However, after less than a year, McKinley returned to Ohio and was admitted to the bar in Warren in March 1867.

That same year, he moved to Canton, the county seat of Stark County, where he established a small law office. He soon partnered with George W. Belden, an experienced lawyer and former judge. This partnership proved successful, allowing William McKinley to invest in a block of buildings on Main Street in Canton, providing him with a steady rental income for years.

William McKinley first foray into politics came when he supported his Army friend Rutherford B. Hayes during Hayes’s gubernatorial campaign in 1867, helping him win in a closely divided county. In 1869, McKinley ran for Stark County prosecuting attorney, traditionally a Democratic seat, and won unexpectedly. However, he was defeated in his re-election bid in 1871.

While his legal career flourished, William McKinley social life also blossomed as he courted Ida Saxton, the daughter of a prominent Canton family. They married on January 25, 1871, in the First Presbyterian Church of Canton. Their first daughter, Katherine, was born on Christmas Day in 1871, followed by a second daughter, Ida, who tragically died the same year. Ida McKinley fell into a deep depression after the loss of her children, with their second daughter, Katherine, dying from typhoid fever two years later. Ida’s health deteriorated, and she developed epilepsy, relying heavily on McKinley for support.

Despite the challenges, Ida encouraged her husband to continue his legal and political career. William McKinley campaigned for Hayes again in 1875 and defended striking coal miners in a high-profile case, gaining respect among laborers, which proved beneficial in his later congressional campaigns. In August 1876, McKinley was nominated for Ohio’s 17th congressional district, winning the election while campaigning on a protective tariff platform, marking the beginning of his significant political career.

Rising Politician (1877–1895)

William McKinley began his congressional career in October 1877, when President Hayes convened a special session of Congress. As a freshman in a minority party, McKinley faced limited committee assignments, but he committed himself to his responsibilities. Although he maintained a friendship with Hayes, their differing views on currency reform did not affect their relationship. The Coinage Act of 1873 effectively placed the U.S. on the gold standard, leading to heated debates over whether to reinstate silver as legal tender. McKinley broke ranks with his party’s leadership by supporting the Bland-Allison Act of 1878, which mandated the government purchase silver, an action that aligned with the interests of many constituents seeking inflationary relief.

From the onset of his congressional career, William McKinley championed protective tariffs, advocating for policies that would benefit American manufacturers by providing them a competitive edge over foreign imports. His advocacy was partly shaped by the economic prosperity in Canton, where protectionist measures had helped local industries thrive. He quickly established himself as a prominent figure in national politics, joining the powerful House Ways and Means Committee after Garfield’s election in 1880. McKinley’s influence grew as he chaired the committee that advanced the McKinley Tariff of 1890, designed to bolster American industries through higher import duties.

Throughout this period, William McKinley faced attempts by Democrats to gerrymander him out of office. Despite these challenges, he consistently returned to Congress, even overcoming redistricting efforts that sought to dilute his support. In 1892, he was elected governor of Ohio, leveraging his popularity and the backing of key party figures like Mark Hanna. While serving as governor, he adeptly navigated labor issues, promoting arbitration and protecting workers’ rights.

The political landscape shifted dramatically with the Panic of 1893, which led to financial difficulties for many, including William McKinley. However, his support from wealthy allies enabled him to repay debts, further endearing him to the public. In the aftermath, McKinley easily won re-election as governor, and his successful campaigning for Republican candidates in the 1894 midterm elections solidified his standing within the party. As the Ohio Republican Party united behind him, McKinley prepared to extend his political ambitions to the national stage.

Election of 1896

William McKinley’s path to the presidency in the 1896 election was marked by strategic planning and strong support from his close friend and adviser, Mark Hanna. Although it remains unclear when McKinley seriously began contemplating a presidential run, he and Hanna had developed a collaborative relationship since 1888. With Hanna’s organizational skills and financial backing, McKinley built a network of supporters throughout 1895 and early 1896, positioning himself as the leading Republican candidate.

While other potential candidates, such as Speaker Thomas Reed and Senator William B. Allison, attempted to organize support for their campaigns, they found themselves outmaneuvered by Hanna’s agents, who had already established connections. Historian Stanley Jones noted that the momentum was clearly in William McKinley favor from the outset, as competing campaigns struggled to gain traction.

Hanna strategically engaged with key Republican political figures in the East, including Senators Thomas Platt and Matthew Quay, who were willing to back William McKinley nomination in exchange for patronage promises. Despite this, McKinley insisted on securing the nomination without resorting to deals, demonstrating a desire to maintain integrity in his campaign. Early efforts targeted the South, where McKinley garnered significant delegate support, with Hanna even acquiring a vacation home in southern Georgia to facilitate meetings with local Republicans. By the time the convention approached, McKinley had secured nearly half of the 453½ delegate votes needed for the nomination.

As the June 1896 Republican National Convention convened in St. Louis, William McKinley support continued to grow, particularly in critical states like Illinois, where he achieved a near-sweep of delegates. Former President Benjamin Harrison’s decision not to enter the race further solidified McKinley’s position, allowing him to quickly gain control in Indiana. By the time the convention began, McKinley had a clear majority, and he monitored events from his home in Canton, Ohio, receiving updates by telephone.

When the roll call reached Ohio, William McKinley officially secured the nomination, which he celebrated with family and supporters. The convention also nominated Garret Hobart of New Jersey as the vice-presidential candidate, a choice largely orchestrated by Hanna. Although Hobart was not widely recognized, he was seen as a safe selection who would not detract from the ticket. McKinley’s nomination and the unity of his supporters marked a pivotal moment in his quest for the presidency, setting the stage for a competitive general election campaign.

General Election Campaign of 1896

As the 1896 election approached, William McKinley’s strategy began to crystallize, particularly regarding the contentious currency question. Initially, McKinley adopted a cautious stance, favoring a moderate position that sought to achieve bimetallism through international agreement. However, as the Republican National Convention drew near, he shifted toward endorsing the gold standard, while still allowing for the possibility of bimetallism through coordination with other nations. This decision led to a split at the convention, with some western delegates, including Colorado Senator Henry M. Teller, walking out in protest. Nonetheless, Republican divisions on this issue were minimal compared to the Democrats, especially since McKinley promised future concessions to silver advocates.

The economic turmoil of the era had empowered the pro-silver movement within the Democratic Party. President Grover Cleveland firmly supported the gold standard, but many rural Democrats, particularly in the South and West, were in favor of silver. The Democratic National Convention eventually succumbed to the silverite faction, leading to the nomination of William Jennings Bryan, who electrified the delegates with his famous “Cross of Gold” speech. Bryan’s radical stance on financial issues alarmed bankers, who believed his proposals could destabilize the economy. In response, Hanna sought financial backing from these bankers, successfully securing $3.5 million for campaign efforts, which included the distribution of over 200 million pamphlets advocating the Republican stance on monetary and tariff issues.

In contrast, Bryan’s campaign had an estimated budget of only $500,000. Leveraging his charisma and youthful energy, he embarked on an extensive whistle-stop tour by train, a tactic that was innovative for the time. However, William McKinley chose a different approach. Citing Bryan’s superior speaking skills, he opted for a “Front Porch Campaign,” where he remained at his home in Canton, Ohio, inviting delegations to visit him. This strategy proved effective, as McKinley made himself accessible to the public nearly every day except Sunday. Railroads facilitated this by offering low excursion rates, resulting in large groups of supporters visiting his home.

William McKinley carefully managed these interactions, ensuring his speeches were scripted and tailored to the interests of each delegation, thereby avoiding unscripted remarks that could potentially harm his campaign. This meticulous approach allowed McKinley to maintain control over his messaging.

The media landscape of the election was fiercely polarized. While most Democratic newspapers refrained from endorsing Bryan, some, like the New York Journal controlled by William Randolph Hearst, supported him. The Republican campaign utilized sharp cartoons and biased reporting to depict Hanna as a plutocrat and William McKinley as his puppet. These portrayals contributed to lasting impressions of both figures in American political history.

The 1896 campaign became a battleground of ideas, with both parties distributing pamphlets extensively. Voters engaged deeply with these materials, analyzing and debating the economic arguments presented. However, William McKinley believed that the monetary issue would soon recede in importance. He underestimated the persistence of silver and gold as central themes in the campaign.

Realignment of 1896

The 1896 presidential election marked a significant realignment in American politics, establishing new voting patterns that reshaped the political landscape for decades. William McKinley campaign, which emphasized a stronger central government to foster American industry through protective tariffs and a commitment to the gold standard, resonated with a rapidly industrializing nation. His victory signified a decisive break from the near deadlock between the major parties that had characterized the Third-Party System since the Civil War.

William McKinley triumph not only solidified Republican dominance but also laid the groundwork for what historians refer to as the Fourth Party System, which lasted until 1932. This era would eventually culminate in another realigning election when Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal coalition emerged as a formidable political force.

Kevin Phillips, a noted political analyst, posits that William McKinley was likely the only Republican capable of defeating Bryan in 1896. He argues that Eastern Republican candidates would have struggled against Bryan, particularly in the critical Midwest, where Bryan’s populist appeal resonated strongly with rural voters. In contrast, McKinley’s platform attracted support from a different demographic—an increasingly industrialized and urbanized America that sought stability and economic growth.

This realignment reflected broader societal changes as the nation grappled with issues of industrialization, urbanization, and economic policy. William McKinley focus on protective tariffs and a gold-based monetary system appealed to the interests of industrialists and urban workers, while Bryan’s campaign, which centered on bimetallism and the interests of rural farmers, highlighted the growing divide between these two constituencies.

The 1896 election thus signified not only a shift in party dominance but also a reconfiguration of the political alliances and priorities that would define American politics for the next several decades. William McKinley victory effectively ushered in an era of Republican hegemony, influencing policy directions and electoral strategies that would shape the nation’s economic and political landscape well into the 20th century.

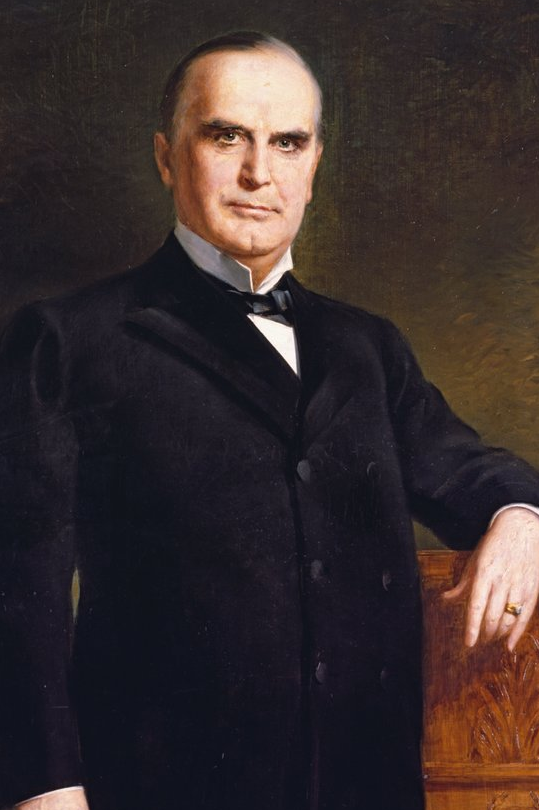

The Presidency of William McKinley: A Transitional Era (1897–1901)

William McKinley assumed office on March 4, 1897, delivering a passionate inaugural address emphasizing tariff reform and diplomatic restraint. He expressed his commitment to avoid foreign conflicts, stating, “We want no wars of conquest.” However, his presidency would soon be marked by significant international and domestic challenges.

One of McKinley’s most debated Cabinet choices was John Sherman as Secretary of State. Though Sherman had a strong reputation, his advancing age led to concerns about his mental acuity. Despite political whispers, McKinley stood by his decision, dismissing rumors about Sherman’s health. His Cabinet also included prominent figures like Lyman J. Gage as Secretary of the Treasury and Theodore Roosevelt, reluctantly chosen as Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

William McKinley presidency became notably intertwined with the Spanish-American War. Public sentiment increasingly favored intervention as Cuban rebels fought for independence from Spanish rule. Despite McKinley’s preference for diplomacy, the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor in 1898 ignited calls for war. Congress declared war on Spain, leading to swift victories in both the Caribbean and Pacific, notably in Cuba and the Philippines.

The war concluded with the Treaty of Paris in 1898, granting the United States control over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. William McKinley faced criticism for expanding American imperialism, but he maintained that these territorial gains were necessary to secure the nation’s future on the global stage. His administration also focused on economic policies, including the passage of the Dingley Tariff Act, which reinforced protectionism to safeguard American industries.

Funeral, Memorials, and Legacy of William McKinley

Funeral and Resting Place

The nation mourned deeply upon the death of President William McKinley. Historian Lewis L. Gould observed, “The nation experienced a wave of genuine grief at the news of McKinley’s passing.” Despite the stock market suffering a sharp decline in the immediate aftermath of his assassination, the public’s attention was solely on the president’s funeral arrangements.

The president’s body was first laid in the East Room of the White House before being moved to the Capitol, where it lay in state. An estimated 100,000 people passed by his casket in the Capitol Rotunda, braving long waits and rain to pay their respects. The casket was then transported to Canton, Ohio, by train, where a similar number of mourners visited his resting place at the Stark County Courthouse.

On September 18, 1901, a funeral service was held at the First Methodist Church in Canton. Afterward, the casket was sealed and taken to William McKinley home, where close family members paid their final respects. His body was temporarily placed in a receiving vault at West Lawn Cemetery in Canton while plans for a permanent memorial were underway.

Many believed that McKinley’s wife, Ida, who had long suffered from ill health, would not survive her husband’s death for long. One family friend even remarked that they should prepare for a “double funeral” while William McKinley lay dying. However, Ida McKinley outlived her husband by six years. Though she was too frail to attend the services in Washington or Canton, she listened from a nearby room as her husband was eulogized. She continued to live in Canton, frequently visiting his vault until her own death in 1907. William and Ida McKinley, along with their two daughters, are interred in the grand marble memorial atop a hill in Canton, Ohio.

Other Memorials

The impact of William McKinley presidency and his tragic death is memorialized in numerous ways across the United States. The William McKinley Monument stands proudly in front of the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, while a large statue honors him at his birthplace in Niles, Ohio. Several schools and public buildings in Ohio and across the country bear his name, and nearly a million dollars was raised in the year following his death for the creation of various memorials.

Statues and monuments dedicated to William McKinley can be found in more than a dozen states. Streets, civic organizations, and libraries have also been named in his honor, keeping his legacy alive. Perhaps the most notable tribute came in 1896 when a gold prospector named North America’s tallest mountain, located in Alaska, “Mount McKinley.” Although the mountain bore his name for many years, the name was reverted to “Denali” in 2015 by the U.S. Department of the Interior, reflecting the indigenous name for the mountain. Denali National Park, formerly known as Mount McKinley National Park, also honors the history surrounding the president.

William McKinley legacy endures through these memorials, signifying his importance not only to Ohio but also to the nation as a whole. Though his assassination cut his presidency short, the public remembrance of him reflects the esteem in which he was held during his life and after his tragic death.