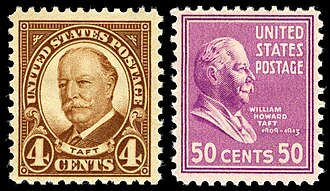

William Howard Taft, born on September 15, 1857, and passing away on March 8, 1930, was a notable figure in American history, distinguished as both the 27th President of the United States and the 10th Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He remains the only individual to have held both of these prestigious offices. Serving as President from 1909 to 1913 and later as Chief Justice from 1921 to 1930, William Howard Taft career spanned both the executive and judicial branches of government. His presidency, however, was overshadowed by his predecessor and mentor, Theodore Roosevelt, and his political legacy was affected by the Republican Party’s division during the 1912 election, which allowed Woodrow Wilson to win.

William Howard Taft was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, into a prominent family. His father, Alphonso Taft, had served as both U.S. Attorney General and Secretary of War, which provided young William with early exposure to the political landscape. Taft attended Yale University, where he became a member of the secret society Skull and Bones, which had been co-founded by his father. After completing his studies, he pursued a legal career, quickly ascending the ranks of the judiciary. By his late twenties, Taft had already been appointed as a judge, and his career continued to flourish with appointments such as U.S. Solicitor General and a judge for the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

In 1901, President William McKinley appointed William Howard Taft as the civilian governor of the Philippines, where he oversaw the administration of the U.S. territory. His success in this role garnered him a reputation as an effective administrator, and in 1904, Theodore Roosevelt selected him to serve as Secretary of War. Though Taft aspired to become a Supreme Court justice, he followed Roosevelt’s lead in political matters and was ultimately handpicked as Roosevelt’s successor. In the 1908 election, with Roosevelt’s backing, Taft won the presidency by defeating William Jennings Bryan.

William Howard Taft, 27th President of the United States

Once in office, William Howard Taft focused on foreign policy, particularly in East Asia and Latin America. His administration frequently intervened in the political affairs of Latin American countries, reflecting the era’s belief in U.S. influence over the Western Hemisphere. Domestically, Taft faced the challenge of managing the Republican Party, which was increasingly divided between its conservative and progressive factions. Although he sought to reduce trade tariffs, the final legislation was seen as heavily influenced by special interests, a move that alienated many progressives.

The growing ideological rift between William Howard Taft and Roosevelt, particularly over issues like conservation and antitrust cases, led to a personal and political break between the two men. Roosevelt, increasingly aligned with the progressive wing of the party, challenged Taft for the Republican nomination in the 1912 election. Although Taft won the nomination, Roosevelt bolted from the party and ran as a third-party candidate under the Progressive Party banner, also known as the Bull Moose Party. This split in the Republican vote handed the presidency to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Taft’s defeat was stark—he carried only two states, Utah and Vermont.

After leaving the White House, William Howard Taft returned to academia, teaching at Yale University. He remained politically active, particularly in his efforts to promote peace through the League to Enforce Peace, an organization advocating for international cooperation to prevent war. Despite his political setbacks, Taft’s judicial aspirations were fulfilled in 1921 when President Warren G. Harding appointed him as Chief Justice of the United States. This appointment marked the realization of a lifelong goal for Taft, and he thrived in the role, focusing on reforming the federal judiciary and advocating for a more efficient court system.

As Chief Justice, William Howard Taft was a conservative voice, particularly on business-related issues, but he also presided over cases that expanded individual rights. His tenure on the court was marked by a pragmatic approach to the law, and he played a key role in modernizing the judiciary. However, as his health began to decline in the late 1920s, Taft resigned from his position in February 1930, just a month before his death in March of that year.

William Howard Taft legacy as president is often viewed through a mixed lens. Although he achieved significant accomplishments, including the establishment of a more organized federal judiciary, his presidency was marred by his failure to unite the Republican Party and his inability to keep pace with the progressive momentum that Roosevelt had initiated. His cautious approach to leadership, in contrast to Roosevelt’s dynamic and aggressive style, led many progressives to become disillusioned with his administration.

Nevertheless, William Howard Taft contributions to the judicial branch, particularly during his tenure as Chief Justice, are often regarded as the highlight of his career. Under his leadership, the Supreme Court became a more professional and efficient institution. He remains the only U.S. president to later serve as Chief Justice, and his dedication to both roles left an indelible mark on the nation’s history.

William Howard Taft was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, making him the first president and the first Chief Justice to be interred there. While he is often ranked near the middle of the pack in historical rankings of U.S. presidents, his judicial legacy is held in high regard, with many legal scholars recognizing his contributions to the development of the U.S. legal system. His unique place in history as both president and chief justice underscores the breadth of his service to the nation, and his role in shaping both the executive and judicial branches of government remain a significant part of his legacy.

Early Life and Family Background

William Howard Taft was born on September 15, 1857, in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Alphonso Taft and Louise Torrey. His father was a prominent figure in public service, holding positions such as U.S. Secretary of War, Attorney General, and ambassador, shaping the family’s tradition of dedication to civic duty.

Education and College Life

William Howard Taft attended Woodward High School in Cincinnati before enrolling at Yale College in 1874. At Yale, he was popular and excelled in sports, even becoming the heavyweight wrestling champion. Though not considered the most brilliant student, William Howard Taft was known for his hard work and integrity. He graduated second in his class in 1878 and joined the prestigious Skull and Bones society.

Legal Training and Early Career

After Yale, William Howard Taft studied law at Cincinnati Law School, graduating in 1880 with a Bachelor of Laws. During this time, he gained hands-on experience covering courts for The Cincinnati Commercial newspaper and reading law in his father’s office. Taft passed the bar exam just before graduating, beginning his path to a successful legal and political career.

Rise in Government (1880–1908)

Early Legal Career and Judgeship

After passing the Ohio bar in 1880, William Howard Taft began his legal career as an assistant prosecutor in Hamilton County, Ohio. Though he was offered a permanent job at the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper, he chose to continue in law. His judicial career began in 1887 when he was appointed to the Superior Court of Cincinnati by Governor Joseph Foraker. At the age of 29, William Howard Taft handled important labor law cases, such as Moores & Co. v. Bricklayers’ Union No. 1, where he ruled against secondary boycotts by unions, a decision that would later be used against him when he ran for president.

William Howard Taft also built a reputation as a fair and diligent judge during this time. His commitment to law and order laid the foundation for his future in higher government roles.

Solicitor General and Federal Judge

In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison appointed William Howard Taft as the U.S. Solicitor General, where he won 15 out of the 18 cases he argued before the Supreme Court. Taft introduced a significant policy known as the “confession of error,” allowing the government to admit when a lower court had wrongly ruled in its favor. This practice continues in U.S. courts today.

In 1892, William Howard Taft was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. As a federal judge, he gained prominence for his work on antitrust cases, most notably his ruling in United States v. Addyston Pipe and Steel Co., which upheld the Sherman Antitrust Act. His decisions reflected a balanced approach to labor rights; for example, he supported workers’ right to strike but ruled against practices that he saw as illegal or harmful to commerce.

Governor of the Philippines

In 1900, President William McKinley appointed William Howard Taft to head a commission in the Philippines, which was under U.S. control after the Spanish-American War. Taft was tasked with establishing a civilian government, and he became the first U.S. civilian governor of the Philippines in 1901. Taft believed in preparing the Filipinos for eventual self-governance and worked to integrate them into administrative roles, although he viewed full independence as a distant goal. He was noted for treating Filipinos as social equals, a progressive stance at the time.

His tenure in the Philippines also involved delicate negotiations with the Catholic Church over land rights, which he managed by arranging the purchase of lands held by Spanish religious orders, easing tensions between the Church and local Filipino communities.

Secretary of War and Panama Canal

In 1904, William Howard Taft became Secretary of War under President Theodore Roosevelt. In this role, he oversaw the construction of the Panama Canal and maintained responsibility for U.S. interests in the Philippines. He also played a key role in stabilizing Cuba in 1906, serving briefly as the island’s provisional governor to prevent political collapse.

During his time as Secretary of War, William Howard Taft became a trusted confidant and “troubleshooter” for Roosevelt, solidifying his standing as a likely candidate for the presidency in 1908.

Presidential Election of 1908

William Howard Taft’s path to the presidency in 1908 was deeply influenced by Theodore Roosevelt, his close friend and political ally. After serving as president for nearly four years following William McKinley’s assassination, Roosevelt had won re-election in 1904. On election night, he promised not to seek another term in 1908, a decision he later regretted but felt bound to honor. Roosevelt saw William Howard Taft, who served as Secretary of War, as his logical successor and used his political influence to ensure Taft’s nomination, despite Taft’s initial reluctance to run for president.

Roosevelt’s control over the Republican Party’s machinery helped smooth William Howard Taft path to the nomination. Key figures, such as Assistant Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock, joined the Taft campaign, while other potential candidates like New York Governor Charles Evans Hughes were sidelined. Roosevelt actively campaigned for Taft, discouraging any efforts to draft him for another term.

At the 1908 Republican National Convention, William Howard Taft won the nomination with ease. However, he did not have full control over his running mate selection, as the convention chose Congressman James S. Sherman of New York, a conservative, instead of a more progressive candidate Taft had hoped for.

The General Election Campaign

In the general election, William Howard Taft faced off against Democrat William Jennings Bryan, who was running for president for the third time. Bryan attempted to position himself as the true successor to Roosevelt’s reform agenda, emphasizing his longstanding support for policies that Roosevelt had championed. Bryan also called for further restrictions on corporate contributions to political campaigns, a position Taft only partially supported, advocating for transparency but preferring to reveal contributions after the election.

1908 William Howard Taft /Sherman poster

William Howard Taft campaign was heavily influenced by Roosevelt, so much so that humorists at the time joked that “TAFT” stood for “Take advice from Theodore.” Taft frequently visited Roosevelt for advice, which fueled accusations that he wasn’t independent or capable of leading on his own. Despite this, Taft supported Roosevelt’s progressive reforms, though he preferred to implement them through legislative action rather than through executive power.

Throughout the campaign, William Howard Taft emphasized economic reform, including supplementing the Sherman Antitrust Act and reforming the currency system to provide more flexibility during economic downturns. He also supported an income tax, despite prior Supreme Court rulings that had struck down such a tax as unconstitutional. Bryan, meanwhile, advocated for a more radical approach, such as government ownership of railroads, which Taft opposed.

Though the campaign saw heated debates, William Howard Taft won the election comfortably. He received 321 electoral votes to Bryan’s 162, though his margin in the popular vote was slimmer, with 51.6% of the vote. Roosevelt’s strong backing had certainly played a significant role in Taft’s success.

Inauguration and Early Presidency of William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft was inaugurated as the 27th President of the United States on March 4, 1909, during a fierce winter storm that forced the ceremony indoors to the Senate Chamber, a rare departure from tradition. In his inaugural address, William Howard Taft expressed deep respect for his predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt, pledging to continue Roosevelt’s reform efforts. He promised to maintain and enforce policies that supported both progressive reforms and business stability. His goals included reducing the 1897 Dingley tariff, advancing antitrust reform, and promoting self-governance in the Philippines.

1909 inauguration

Unlike the dynamic and charismatic Roosevelt, William Howard Taft brought a quieter, more judicial approach to the presidency, focusing on the rule of law. This shift in leadership style marked a notable departure from Roosevelt’s more personal and media-friendly relationship with the public. Taft avoided frequent interviews and photo opportunities, preferring a more restrained approach to interacting with the press.

Roosevelt’s departure to Africa for a year-long hunting expedition helped avoid potential political interference during William Howard Taft early presidency. Roosevelt had a bittersweet parting with the office he loved, and he trusted Taft to carry forward the progressive agenda.

William Howard Taft Cabinet and Leadership

Upon taking office, William Howard Taft made key appointments to his cabinet. He retained Agriculture Secretary James Wilson and Postmaster General George von Lengerke Meyer, the latter of whom he transferred to the Navy Department. Other significant appointments included Philander Knox, a former attorney general under McKinley and Roosevelt, as Secretary of State, and Franklin MacVeagh as Treasury Secretary. These appointments reflected continuity but also signaled Taft’s desire to surround himself with experienced figures.

While William Howard Taft administration was quieter and more restrained, he was committed to ensuring that the reforms established under Roosevelt would be enduring, offering stability to businesses that feared radical policy changes.

First Lady Nellie William Howard Taft Illness

A major personal challenge early in William Howard Taft presidency was his wife Nellie’s severe stroke in May 1909. The stroke left her partially paralyzed and unable to speak. Taft devoted much of his time to her care, spending hours each day helping her regain her ability to speak. It took nearly a year for her to recover some of her speech and mobility, which significantly impacted Taft’s focus during his early administration.

William Howard Taft Foreign Policy and Global Diplomacy

Restructuring the State Department

William Howard Taft prioritized modernizing the State Department, which he believed was operating under outdated principles. He and his Secretary of State, Philander Knox, organized the department into geographic divisions to handle the growing complexity of global diplomacy. For the first time, desks were created for the Far East, Latin America, and Western Europe, reflecting the U.S.’s evolving foreign interests. The department also launched its first in-service training program, giving appointees a month of preparation in Washington before assuming their overseas posts.

While William Howard Taft and Knox agreed on major goals, Knox struggled with poor diplomatic relationships, particularly in Latin America, which affected the administration’s foreign policy success. Still, Taft used the State Department to bolster U.S. business interests abroad, pushing the agenda of “Dollar Diplomacy”—a policy aimed at promoting American investment to further both economic and diplomatic goals, particularly in Latin America and Asia.

Tariffs and Reciprocity with Canada

Tariff policy was a cornerstone of William Howard Taft domestic and foreign policy. At the time, protectionism, through high tariffs, was central to the Republican platform, and Taft’s presidency witnessed debates over revising the Dingley Act, a tariff law designed to protect U.S. industries from foreign competition. In 1909, Taft called a special session of Congress to address this issue, resulting in the Payne-Aldrich Tariff. Though Taft believed the bill moderately reduced tariffs, amendments in the Senate raised rates on many items, angering progressive Republicans who sought deeper reductions. The controversy weakened Taft’s support among progressives and marred his presidency.

William Howard Taft also attempted to negotiate a free trade agreement with Canada, an effort rooted in his belief that reducing trade barriers would benefit both nations. While the agreement passed in the U.S. Congress, it failed in Canada after a heated debate led to the fall of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s government. This setback in cross-border trade relations deepened divisions within the Republican Party.

Latin America and Dollar Diplomacy

William Howard Taft approach to Latin America was characterized by the doctrine of “Dollar Diplomacy.” This policy encouraged U.S. businesses to invest in Latin America, with the belief that economic engagement would promote stability and reduce European influence in the region. However, many Latin American countries resisted U.S. involvement, viewing it as neo-colonial interference. Even within the U.S. Senate, there was opposition to this interventionist approach.

One of the most significant foreign challenges William Howard Taft faced was the Mexican Revolution. The long-standing dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz collapsed as revolutionaries, led by Francisco Madero, sought to overthrow the regime. Taft supported Díaz initially, even meeting with him in Ciudad Juárez in 1909, making it the first meeting between a U.S. and Mexican president. However, the unrest in Mexico continued, leading to conflicts along the U.S.-Mexico border. Taft resisted calls for aggressive U.S. military intervention, preferring a cautious approach, despite mounting tension.

In Nicaragua, Taft’s administration supported rebels against President José Santos Zelaya, who threatened to revoke concessions granted to American companies. This intervention culminated in the U.S. occupation of Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933, ensuring control over a potential canal route and protecting American financial interests.

Relations with East Asia and China

With extensive experience in the Philippines, William Howard Taft was deeply interested in East Asian affairs. He and Knox tried to extend the Open Door Policy in China, aiming to prevent any single power from dominating trade in the region. They succeeded in including U.S. banks in a British-led railroad project in China, but the agreement sparked protests from local shareholders, contributing to the revolution that led to the fall of the Manchu dynasty in 1911.

While public opinion in the U.S. favored recognizing the new Chinese Republic, William Howard Taft was hesitant, preferring to wait for a unified response from Western powers. He maintained restrictive immigration policies for Chinese and Japanese workers, continuing Roosevelt’s Gentlemen’s Agreement to limit Japanese immigration to the U.S. Despite growing trade between Japan and the U.S., immigration remained a contentious issue, particularly on the West Coast.

European Diplomacy and Arbitration

In Europe, William Howard Taft pursued peaceful diplomacy and arbitration to settle international disputes. He negotiated arbitration treaties with Great Britain and France, although they ultimately failed after amendments from the Senate. Despite this setback, Taft successfully resolved several disputes with Britain, including long-standing conflicts over seal hunting in the Bering Sea and fishing rights off Newfoundland. These peaceful resolutions were part of Taft’s broader vision of using diplomacy, rather than force, to resolve global tensions.

However, William Howard Taft approach to foreign diplomacy was not without challenges. His preference for replacing wealthy ambassadors with career diplomats created tensions within the State Department, as many feared losing their positions. Although Taft had a strong commitment to arbitration and diplomatic resolutions, the Senate’s resistance to ceding power over foreign treaties limited the success of many of his initiatives.

William Howard Taft’s presidency (1909–1913)

Antitrust Policies

Building on the legacy of his predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft aggressively pursued antitrust actions, bringing 70 lawsuits against large corporations under the Sherman Antitrust Act, compared to Roosevelt’s 40 in seven years. Two major cases initiated under Roosevelt—the Standard Oil Company and the American Tobacco Company—were decided in favor of the government by the Supreme Court in 1911, reinforcing the administration’s stance against monopolies. However, Taft’s decision to prosecute U.S. Steel, a company Roosevelt had supported during the Panic of 1907, led to a personal rift between the two leaders. Roosevelt felt betrayed when Taft’s administration accused him of fostering monopolies, which fueled Roosevelt’s opposition to Taft in the 1912 presidential election.

Ballinger-Pinchot Affair and Conservation

While William Howard Taft shared Roosevelt’s belief in conservation, he differed in his approach, favoring legislative solutions rather than executive orders. Taft’s dismissal of Gifford Pinchot, the Chief Forester and close ally of Roosevelt, after a public dispute involving Interior Secretary Richard A. Ballinger, further alienated progressives. Pinchot’s vocal criticism of Ballinger’s approval of mining claims in Alaska led to a congressional investigation that, although clearing Ballinger of wrongdoing, damaged Taft’s standing with the conservationist wing of the Republican Party and worsened his relationship with Roosevelt.

Civil Rights

William Howard Taft approach to civil rights was more cautious and conservative compared to Roosevelt. He announced that he would not appoint African Americans to federal positions in the South where it would cause racial friction, marking a departure from Roosevelt’s policy of appointing black Americans to such posts. This policy, known as Taft’s “Southern Policy,” led to a significant reduction in African American officeholders in the South and contributed to a shift of African American voters from the Republican Party to the Democrats over the following decades.

Judicial Appointments

William Howard Taft appointed six justices to the Supreme Court, including promoting Edward Douglass White to Chief Justice, marking the first time an associate justice had been elevated to the position. His appointments, such as Horace H. Lurton and Willis Van Devanter, reflected his conservative legal philosophy and his desire for judicial restraint. Taft also established the Commerce Court to handle appeals related to the Interstate Commerce Commission, though it was abolished shortly after his presidency.

In addition to these judicial appointments, William Howard Taft administration saw the impeachment of Commerce Court judge Robert W. Archbald for corruption, an embarrassment that underscored the challenges in Taft’s judicial reform efforts.

1912 Election and Split with Roosevelt

William Howard Taft relationship with Roosevelt deteriorated further as Roosevelt moved toward a more progressive platform, culminating in Roosevelt’s decision to challenge Taft for the Republican nomination in 1912. After a bitter primary battle, Taft secured the nomination, but Roosevelt bolted the party, forming the Progressive Party (also known as the Bull Moose Party). This splits the Republican vote in the 1912 election, leading to the victory of Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Taft garnered only eight electoral votes, while Roosevelt won 88, and Wilson secured 435.

William Howard Taft loss in 1912 was a repudiation of his presidency by progressives within the Republican Party, who saw him as too conservative and aligned with business interests. Nonetheless, Taft remained a committed conservative, believing that his policies preserved the constitutional foundations of the U.S. government.

Return to Yale (1913–1921)

With no pension or other compensation expected after leaving the White House, Taft considered returning to the practice of law, which he had not pursued for years. However, concerns arose about potential conflicts of interest due to his appointments of many federal judges, including a majority of the Supreme Court. Instead, he accepted an offer to become Kent Professor of Law and Legal History at Yale Law School. After a brief vacation in Georgia, he arrived in New Haven on April 1, 1913, where he received a warm welcome.

As it was too late in the semester for him to teach a formal course, he delivered a series of eight lectures titled “Questions of Modern Government” in May. Throughout his eight years at Yale, William Howard Taft supplemented his income with paid speeches and magazine articles, ultimately increasing his savings. During this time, he also authored the treatise Our Chief Magistrate and His Powers (1916).

In addition to his academic pursuits, William Howard Taft was involved in significant national projects. He had been appointed president of the Lincoln Memorial Commission while still in office, and he humorously remarked that being removed from this position would hurt more than losing the presidency itself. The architect of the memorial, Henry Bacon, preferred Colorado-Yule marble, while southern Democrats advocated for Georgia marble.

William Howard Taft lobbied successfully for the use of the western stone, and the project proceeded, culminating in his dedication of the Lincoln Memorial as chief justice in 1922. In 1913, he was also elected president of the American Bar Association (ABA), where he took a firm stance against opponents like Louis Brandeis and University of Pennsylvania Law School dean William Draper Lewis, who supported the Progressive Party.

Political Relations and International Efforts

William Howard Taft maintained a generally cordial relationship with President Wilson, offering private critiques on various policies while publicly supporting his administration, particularly regarding Philippine policy. Taft was dismayed when Wilson nominated Brandeis to the Supreme Court, as he had not forgiven Brandeis for his role in the Ballinger–Pinchot affair. Despite Taft’s efforts, Brandeis was confirmed by the Senate.

William Howard Taft and Roosevelt, on the other hand, remained estranged. They met only once during the early years of Wilson’s presidency, exchanging polite but brief words at a funeral. Taft became president of the League to Enforce Peace, advocating for an international association of nations to prevent conflicts. As World War I engulfed Europe, he expressed support for Wilson’s foreign policy and even invited the president to speak at a league meeting in May 1916, where Wilson discussed the potential for a postwar international organization.

William Howard Taft actively engaged in Republican politics, attempting to rally support for Justice Hughes as the party’s presidential nominee. He tried to mediate a reconciliation between Roosevelt and himself, but despite a brief moment of goodwill in October 1916, their relationship remained strained. Ultimately, Wilson narrowly won reelection, complicating Taft’s political aspirations.

Support for the War Effort

In March 1917, William Howard Taft publicly demonstrated his support for the U.S. war effort by joining the Connecticut State Guard, which took over state duties while the National Guard was deployed. When Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917, Taft eagerly supported the action, dedicating much of his time to the American Red Cross as chairman of its executive committee. In August 1917, to help the Red Cross function more effectively during wartime, Wilson conferred military titles on its executives, and Taft was appointed a major general.

William Howard Taft took a leave of absence from Yale to serve as co-chairman of the National War Labor Board, which aimed to mediate relations between industry owners and workers. In February 1918, efforts were made by the new Republican National Committee chairman, Will H. Hays, to reconcile Taft with Roosevelt. While dining at the Palmer House in Chicago, Taft learned Roosevelt was present, leading to a warm embrace between the two amid applause. However, their relationship did not significantly progress before Roosevelt’s death in January 1919. Taft reflected on their friendship, stating that had Roosevelt died harboring ill feelings toward him, it would have been a lasting regret.

League of Nations and Political Controversies

William Howard Taft publicly supported Wilson’s proposal for a League of Nations, assuming a leadership role within his party’s activist wing, despite opposition from a faction of senators. His shifting stance on whether the Versailles Treaty required reservations angered members on both sides, prompting some Republicans to accuse him of betraying the party in favor of Wilson. Ultimately, the Senate rejected the Versailles Treaty, illustrating the challenges Taft faced in maintaining a cohesive Republican identity amid a politically divided landscape.

Chief Justice (1921–1930)

Appointment

During the 1920 election campaign, William Howard Taft endorsed the Republican ticket, which included Warren G. Harding and Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge. Following their election victory, Taft was invited to Harding’s home in Marion, Ohio, on December 24, 1920, to discuss judicial appointments. According to Taft’s later accounts, after some conversation, Harding casually asked if Taft would accept a Supreme Court appointment.

William Howard Taft replied that he could only accept the chief justice position due to his previous experience as president and his opposition to Justice Brandeis. While Harding did not immediately respond, Taft reiterated his condition in a thank-you note, mentioning that Chief Justice Edward Douglass White had previously indicated he was holding the position for Taft until a Republican was in office.

Although White’s health was declining, he did not retire immediately when Harding took office on March 4, 1921. William Howard Taft visited White on March 26 and found him still engaged in his duties without plans to step down. White ultimately passed away on May 19, 1921. Taft expressed admiration for White and anxiously awaited his potential appointment as White’s successor. Despite speculation surrounding his selection, Harding delayed an announcement.

It later became known that Harding had also promised former Senator George Sutherland a Supreme Court seat and was considering a proposal by Justice William R. Day for a temporary chief justiceship. William Howard Taft, upon learning of this plan, felt a short-term appointment would not honor the office. After Harding rejected Day’s proposal, Taft was appointed Chief Justice on June 30, 1921, with the Senate confirming him 61–4 the same day, without committee hearings and after minimal debate. He became the first individual to serve as both president and chief justice of the United States.

Jurisprudence

The William Howard Taft Court, which served under his leadership, adopted a conservative approach, particularly concerning the Commerce Clause. This resulted in increased difficulty for the federal government to regulate industries and led to the invalidation of numerous state laws. Although justices like Louis Brandeis, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., and Harlan Fiske Stone occasionally dissented, they often aligned with the majority opinions.

In Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), the White Court had already overturned a congressional attempt to regulate child labor. William Howard Taft furthered this conservative trend in Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. (1922), where he ruled that a tax imposed on corporations using child labor was unconstitutional, arguing that it was an overreach of federal authority to regulate matters reserved for the states. However, in Stafford v. Wallace, William Howard Taft sided with the majority in asserting that the processing of animals in stockyards fell under Congress’s jurisdiction as it directly affected interstate commerce.

One of the few cases where William Howard Taft dissented was Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923), where the Court struck down a minimum wage law for women in Washington, D.C. William Howard Taft disagreed with the majority, expressing that the recent ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment did not equate to equality in bargaining power, indicating a more expansive view of government intervention than he typically exhibited.

In Balzac v. Porto Rico (1922), a significant ruling concerning the powers of government, William Howard Taft led a unanimous decision stating that residents of Puerto Rico, not designated for statehood, would only receive constitutional protections as Congress granted. This ruling emphasized the limited application of the Bill of Rights in non-state territories.

In Myers v. United States (1926), William Howard Taft opined that Congress could not mandate presidential approval for the removal of appointees, affirming the president’s removal powers outlined in the Constitution. He regarded this ruling as one of his most significant opinions. The following year, in McGrain v. Daugherty, the Court upheld Congress’s authority to conduct investigations, reinforcing the legislative body’s investigative powers.

Individual and Civil Rights

The William Howard Taft Court laid the groundwork for applying many Bill of Rights guarantees against the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. In Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Court upheld Gitlow’s conviction for advocating government overthrow while acknowledging that free speech protections applied to state actions. This case marked a significant step towards incorporating First Amendment rights at the state level.

Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) was another important ruling, where the William Howard Taft Court struck down an Oregon law that sought to eliminate private schools, affirming the rights of parents in education while supporting religious freedoms.

In United States v. Lanza (1922), William Howard Taft ruled that a defendant could face both state and federal prosecutions for the same act, reinforcing the concept of dual sovereignty. Similarly, in Lum v. Rice (1927), the Court upheld racial segregation in public schools, allowing states to exclude children of Chinese ancestry, a decision that sparked significant dissent.

Administration and Political Influence

William Howard Taft actively sought to exert influence over his fellow justices, promoting consensus and discouraging dissent within the Court. His expansive view of the chief justice’s role was contrasted with his earlier, more restrained view of presidential power. Initially, he supported President Coolidge but became disillusioned with Coolidge’s judicial appointments and those of his successor, Herbert Hoover.

Believing the Chief Justice should oversee the federal courts, William Howard Taft advocated for administrative support and greater authority to temporarily reassign judges to address the federal courts’ inefficiencies. He prioritized legislative initiatives to address the congested docket caused by wartime litigation, leading to the introduction of a bill for additional judges and the creation of a Judicial Conference.

William Howard Taft efforts culminated in the Judges’ Bill, which passed in February 1925, allowing the Court to manage its docket more effectively. Additionally, he initiated efforts to secure a dedicated Supreme Court building, which Congress approved in 1927, though the Court did not occupy the new facility until 1935.

Declining Health and Death

William Howard Taft, who stands as the heaviest president in U.S. history, reached his peak weight of approximately 335–340 pounds toward the end of his presidency, despite a notable reduction to 244 pounds by 1929. His health began to decline as he assumed the role of chief justice in 1921. To combat this, Taft instituted a daily fitness regimen that included walking three miles to the Capitol from his home, often returning via a specific route that featured the crossing over Rock Creek, which was later named Taft Bridge in his honor.

William Howard Taft commitment to health extended to dietary management; he enlisted British doctor N. E. Yorke-Davies as a dietary advisor. Their correspondence spanned over two decades, during which Taft meticulously documented his weight, food intake, and physical activities.

Despite his declining health, Taft remained engaged in his duties. At Herbert Hoover’s inauguration in March 1929, Taft mistakenly recited part of the oath of office, admitting later that his memory had faltered. As his health deteriorated further, he expressed concerns about the possibility of a progressive successor to the chief justice position, preferring Charles Evans Hughes. He delayed his resignation until he received assurances that Hughes would be appointed.

On February 3, 1930, Taft resigned as chief justice, but his health continued to decline. Following the funeral of his brother Charles on December 31, 1929, Taft’s condition worsened significantly. By early January 1930, he was too ill to attend court sessions, relying on others to deliver opinions he had drafted. Despite seeking rest in Asheville, North Carolina, his health plummeted, leading to hallucinations and severe physical decline.

Taft passed away at his home in Washington, D.C., on March 8, 1930, at the age of 72. The cause of death was attributed to heart disease, liver inflammation, and high blood pressure. His body lay in state at the U.S. Capitol rotunda before he became the first president and Supreme Court member to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, with a grave marker sculpted from Stony Creek granite by James Earle Fraser.

Legacy and Historical View

Taft’s presidency is often characterized as “undistinguished,” and he is frequently overshadowed by his predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt. Historians and political commentators have argued that Taft did not receive the recognition he deserved for his policy achievements. Lurie noted that Taft’s approach to trust-busting was more aggressive than Roosevelt’s, despite the former president’s more flamboyant political style. This perception of Taft as a “boring” figure may have contributed to his historical reputation.

Scott Bomboy remarked that while William Howard Taft was a multifaceted individual—an intellectual, a reformer, and a passionate baseball fan—his legacy is often reduced to anecdotes about his weight and an unfounded myth about getting stuck in a bathtub. Taft is also noted for being the last U.S. president with facial hair.

While some argue that William Howard Taft lacked the political skills necessary for effective leadership, others acknowledge his accomplishments, including a significant legislative record and the enactment of the Judges’ Bill of 1925, which improved the Supreme Court’s operations. Despite this, Taft’s presidency is frequently remembered through a lens of failure and betrayal, particularly due to the rift with Roosevelt that led to the split of the Republican Party.

The historical assessment of William Howard Taft has evolved over time. Initially viewed as mediocre, he has been reassessed as a competent chief justice, with scholars like Antonin Scalia noting that his contributions should be recognized beyond the narrow view of his judicial conservatism. His efforts to reform the Supreme Court and improve its procedures are often highlighted as significant achievements of his tenure.

William Howard Taft legacy continues to be examined and debated, with a mixed reputation that places him alongside other presidents regarded as historically important, such as James Madison and John Quincy Adams. The National Historic Site in Cincinnati marks his childhood home, preserving his memory for future generations. Taft’s son, Robert, also made notable contributions to American politics, becoming Senate Majority Leader and a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination on multiple occasions.

In conclusion, William Howard Taft’s life and career embody the complexities of American politics in the early 20th century. While his presidency faced challenges and criticisms, his legacy as chief justice and advocate for judicial reform highlights a more nuanced historical perspective, deserving of recognition beyond his physical attributes and perceived shortcomings in leadership.