Thomas Woodrow Wilson, born on December 28, 1856, and passing on February 3, 1924, was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, was the only president from his party during the Progressive Era, a period otherwise dominated by Republicans. Known for his pivotal role in reshaping U.S. economic policies and leading the country through World War I, Wilson was also instrumental in establishing the League of Nations, and his foreign policy approach, Wilsonianism, emphasized principles that continue to influence global diplomacy.

Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia, and raised in the Southern United States during the Civil War and Reconstruction. His early life in the South during these turbulent times greatly influenced his worldview. He went on to earn a Ph.D. in history and political science from Johns Hopkins University, making him the only U.S. president to hold a doctoral degree.

Before his political career, Woodrow Wilson was a professor and served as president of Princeton University, where he became known for his progressive stance on education reform. His strong advocacy for progressivism laid the groundwork for his rise in politics, leading him to serve as the governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913. During his tenure, he pushed through numerous reforms and opposed the state’s political bosses, further solidifying his reputation as a reformist leader.

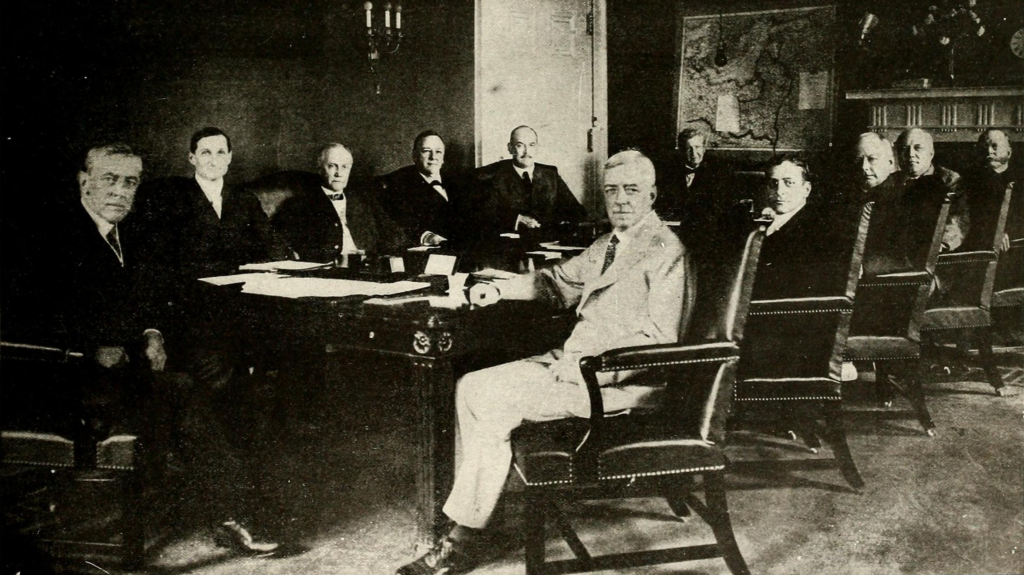

Woodrow Wilson 28th President of the United States

In 1912, Woodrow Wilson ran for president, defeating incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt, who was running as a third-party candidate. Wilson’s victory marked a significant political shift, as he became the first Southern-born president since before the Civil War. However, his progressive image was overshadowed by his support for racial segregation within federal offices and his opposition to women’s suffrage, which drew considerable protest and criticism. Despite these controversies, Wilson pursued an ambitious domestic agenda, known as the “New Freedom,” which aimed at regulating business practices, lowering tariffs, and increasing individual freedoms.

Woodrow Wilson economic reforms included the Revenue Act of 1913, which introduced a federal income tax, and the Federal Reserve Act, which established the Federal Reserve System to stabilize the U.S. banking sector. In 1914, as Europe plunged into World War I, Wilson maintained a policy of neutrality, hoping to keep the U.S. out of the conflict while trying to broker peace between the warring powers. He campaigned for re-election in 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of war” and narrowly won against Republican Charles Evans Hughes.

The U.S., however, did not stay neutral for long. By 1917, German submarine warfare had escalated, and the sinking of American merchant ships became a critical concern. In April 1917, Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, stating that the world must be made “safe for democracy.” During the war, Wilson was heavily involved in diplomacy, crafting his vision for peace in a set of principles known as the Fourteen Points, which outlined his aspirations for a post-war world. These points emphasized self-determination, free trade, and collective security, which would later form the basis of the League of Nations. Although the Allies initially accepted these principles, the complex politics of the post-war negotiations complicated their implementation.

Woodrow Wilson played a central role at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, where he advocated for the establishment of the League of Nations, an international organization aimed at preserving peace and preventing future wars. The League was incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended the war. However, Wilson faced stiff opposition from the Republican-controlled U.S. Senate, which opposed the League due to concerns about American sovereignty. Wilson refused to compromise with Senate Republicans on the treaty’s terms, leading to its rejection and ultimately preventing the U.S. from joining the League of Nations.

In October 1919, while campaigning for public support of the treaty, Woodrow Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke, which left him largely incapacitated. During his remaining time in office, Wilson’s wife, Edith, and his physician closely guarded him, making decisions on his behalf. This effectively limited his ability to govern, though he remained the nominal president until his term ended in March 1921. Wilson’s incapacitation marked one of the first instances in U.S. history where the question of presidential succession became an issue of national importance, raising awareness of the need for clear guidelines on presidential incapacity.

After leaving the presidency, Woodrow Wilson retired to a quiet life in Washington, D.C., where he continued to write and advocate for peace. His dream of a League of Nations continued to influence U.S. foreign policy, and in the following decades, his vision inspired the formation of the United Nations, which sought to prevent conflicts on a global scale. Wilson’s liberal ideals and his promotion of national self-determination have left a lasting legacy, impacting both American diplomacy and international relations.

Woodrow Wilson presidency is often ranked in the upper tier by historians, although his record is marred by his racial policies, particularly the segregation of the federal workforce and his indifference toward civil rights. His progressive domestic policies, while innovative, are overshadowed by his decisions on race, which have prompted contemporary reevaluations of his legacy. Nevertheless, his approach to foreign policy and his contributions to the ideas of self-governance and collective security continue to resonate today, influencing both the U.S. and the world at large.

In recognition of his efforts toward world peace, Woodrow Wilson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919. His advocacy for an international peace organization is one of the most enduring aspects of his legacy, despite the fact that his vision was not realized in his lifetime. Today, Wilson’s legacy remains complex; he is praised for his intellectual contributions and his commitment to peace, while his failures regarding racial equality are acknowledged as significant shortcomings.

Woodrow Wilson Early Life and Education

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born on December 28, 1856, in Staunton, Virginia, into a family of Scotch-Irish and Scottish descent. He was the third of four children and the first son of Joseph Ruggles Woodrow Wilson and Jessie Janet Woodrow. Wilson’s paternal grandparents had immigrated to the U.S. from Strabane, County Tyrone, Ireland, in 1807, settling in Ohio, where his grandfather published an anti-slavery newspaper. His maternal grandfather, Reverend Thomas Woodrow, emigrated from Scotland to Ohio in the late 1830s. Wilson’s family moved to Augusta, Georgia, when he was young, and Wilson’s earliest memories include hearing about the election of Abraham Lincoln and the impending Civil War.

Woodrow Wilson’s father was a staunch Confederate supporter during the Civil War and was one of the founders of the Southern Presbyterian Church. Wilson grew up in the South, with his family residing in Georgia and South Carolina due to his father’s church appointments. In 1873, Wilson became a member of the Columbia First Presbyterian Church, maintaining his affiliation throughout his life.

After attending Davidson College briefly, Woodrow Wilson transferred to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), where he excelled in history, political philosophy, and debating. In 1876, he supported the Democratic presidential candidate Samuel J. Tilden. Wilson later attended the University of Virginia School of Law, though health issues led him to study law independently before being admitted to the Georgia bar in 1882. However, he quickly found legal practice distasteful and decided to pursue an academic career.

In 1883, Woodrow Wilson enrolled at Johns Hopkins University for doctoral studies, focusing on history and political science. During this period, he wrote Congressional Government, which critiqued the workings of the U.S. federal government and garnered positive reviews upon its publication in 1885. In 1886, Wilson earned a Ph.D. in history and government, making him the only U.S. president to hold this degree.

Marriage and Family

In 1883, Wilson met Ellen Louise Axson, a talented artist from Georgia. They married in 1885 after she agreed to pause her art career to support Wilson’s academic ambitions. Together, they had three children: Margaret, Jessie, and Eleanor. Ellen learned German to help Wilson with his academic work, and she provided support throughout his rising career.

Academic Career

Woodrow Wilson began teaching at Bryn Mawr College in 1885, where he taught history and political science but clashed with the administration over his contract. He later accepted a position at Wesleyan University, where he coached football and founded a debate team. In 1890, Wilson joined the College of New Jersey (Princeton University) as Chair of Jurisprudence and Political Economy, quickly gaining renown as an engaging lecturer. His published works, including The State and Division and Reunion, became influential in academia.

In 1902, Woodrow Wilson was appointed president of Princeton University, where he initiated reforms to improve academic standards. He introduced the preceptorial system, expanded admission requirements, and raised funds to improve Princeton’s facilities. Wilson’s attempts to reform the social structure, including his efforts to eliminate upper-class eating clubs, sparked significant opposition from alumni. His tenure as president ended with some disillusionment as he faced resistance from trustees and influential supporters like Grover Cleveland.

Political Aspirations

Woodrow Wilson experiences at Princeton fueled his interest in public service. In 1908, he hinted at a potential political career. Although his ideas were initially viewed as idealistic, he would later emerge as a leading figure in the Democratic Party, eventually ascending to the presidency in 1912. McGeorge Bundy, reflecting on Wilson’s contributions, stated, “Wilson was right in his conviction that Princeton must be more than a wonderfully pleasant and decent home for nice young men; it has been more ever since his time.”

Woodrow Wilson’s tenure as Governor of New Jersey from 1911

1913 marked his transition from academia to politics and established him as a key figure in the Progressive Movement. Initially seen as a suitable yet controllable candidate by New Jersey Democratic leaders, Woodrow Wilson gained the support of influential figures like James Smith Jr. and George Brinton McClellan Harvey. He agreed to run on the condition that he would not be beholden to any special interests, and his victory in the 1910 gubernatorial election came with a significant margin against Republican candidate Vivian M. Lewis, emphasizing his popularity among voters.

Upon taking office, Woodrow Wilson pursued an aggressive reform agenda focused on dismantling political corruption and strengthening regulations. He championed the Geran Bill, which introduced primary elections for all offices, reducing the influence of political bosses. Wilson’s first year also saw the passage of legislation supporting workers’ compensation and restricting child labor, along with laws improving factory safety standards and mandating a fair wage system.

Although Republicans later gained control of the state assembly, limiting Woodrow Wilson influence, he continued his reform efforts. Notable accomplishments included establishing the State Board of Education, introducing free dental clinics, standardizing trained nursing, and abolishing contract labor in reformatories and prisons. Additionally, he endorsed a series of antitrust measures known as the “Seven Sisters,” enhancing New Jersey’s regulatory oversight of large corporations and positioning Wilson as a national progressive leader.

Woodrow Wilson term as governor laid the groundwork for his ascent to the national stage, highlighting his commitment to Progressive ideals and independence from party politics, which helped define his subsequent career as President of the United States.

The 1912 U.S. presidential election was one of the most remarkable in American history, pitting Woodrow Wilson, a reform-minded Democrat, against former President Theodore Roosevelt, running as a Progressive third-party candidate, and incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft. With Roosevelt and Taft splitting the Republican vote, Woodrow Wilson emerged victorious, setting the stage for a transformative presidency.

Presidency (1913–1921)

Woodrow Wilson, having just gained national attention as Governor of New Jersey, became a key contender for the Democratic nomination in 1912. His battles with state political bosses and his alignment with the Progressive movement won him admiration among reformers, though he also faced backlash from some former allies like George Harvey. By July 1911, Wilson had appointed skilled political strategists William Gibbs McAdoo and Edward M. House to lead his campaign, working to secure the endorsement of influential figures such as three-time Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan, whose support could sway the party’s direction.

The main competition in the Democratic primaries came from House Speaker Champ Clark and House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood. While Clark initially led, especially with backing from Tammany Hall, his momentum faltered after Bryan denounced Tammany’s influence. As a result, Woodrow Wilson gained support from critical factions within the Democratic Party, including Southern delegates. After an intense convention battle that required 46 ballots, Wilson secured the nomination, choosing Indiana Governor Thomas R. Marshall as his running mate.

The General Election and Opponents

The general election featured a fractured Republican Party, as Roosevelt, unable to secure the Republican nomination, ran under his newly formed Progressive Party, also known as the “Bull Moose” Party. The four-way race included Woodrow Wilson, Taft, Roosevelt, and Socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs. With the Republican vote split between Taft and Roosevelt, Democrats saw an opening to win their first presidential election since 1892.

Woodrow Wilson and Roosevelt, both progressives, aimed to address social and economic inequalities but differed in their approach. Roosevelt’s “New Nationalism” endorsed a strong regulatory government to oversee large corporations, while Wilson’s “New Freedom” platform advocated breaking up monopolies to create a fair economic environment. Wilson’s campaign, guided by legal scholar Louis Brandeis, called for lowering tariffs and dismantling trusts, aiming to allow small businesses to thrive without interference from powerful corporate interests.

Woodrow Wilson Victory

In a spirited campaign marked by Woodrow Wilson cross-country speaking engagements, he emphasized government’s role in safeguarding citizens’ rights and creating opportunities for all. Rejecting corporate donations, Wilson’s campaign relied on contributions from individual supporters. He ultimately won the election with 42 percent of the popular vote and a sweeping 435 electoral votes. Roosevelt received 27.4 percent of the popular vote and a notable 88 electoral votes, making it one of the strongest showings for a third-party candidate in U.S. history. Taft garnered 23.2 percent of the popular vote and only 8 electoral votes, while Debs took 6 percent.

Woodrow Wilson win marked a shift in American politics, bringing a progressive Democrat to the White House as the first Southern-born president since the Civil War and the first with a Ph.D. His election victory also gave Democrats control of both the House and Senate, setting the stage for an era of reforms aimed at addressing the inequalities of the Gilded Age.

The presidency of Woodrow Wilson, spanning from 1913 to 1921, is marked by a significant domestic legislative agenda, foreign policy challenges, and personal changes in his life. Here’s an overview of key events during his presidency:

Cabinet and Early Administration

Upon his election, Woodrow Wilson selected William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State and formed a cabinet that supported his progressive domestic policies. Key figures included William Gibbs McAdoo as Secretary of the Treasury, and Josephus Daniels, a loyal party member, as Secretary of the Navy. Future president Franklin D. Roosevelt served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Wilson’s most trusted adviser, however, was Edward M. House, whose influence was unparalleled within the administration.

New Freedom Domestic Agenda

Woodrow Wilson sought to implement significant domestic reforms, with a focus on tariff reduction, banking reform, antitrust legislation, and support for farmers. He notably broke tradition by delivering his State of the Union address in person, aiming to push his legislative priorities through Congress.

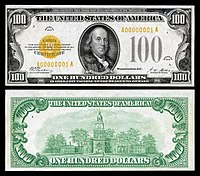

- Tariff Reform: The Revenue Act of 1913, also known as the Underwood Tariff, reduced tariffs and implemented a federal income tax, a key component of Woodrow Wilson reform agenda.

- Banking Reform: Woodrow Wilson most lasting domestic achievement was the establishment of the Federal Reserve System in 1913, providing the U.S. with a central bank to stabilize the economy and control the money supply.

- Antitrust Legislation: In 1914, the Clayton Antitrust Act and the creation of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) strengthened laws against monopolistic practices, addressing concerns over the power of big business.

Labor and Agriculture Reforms

Woodrow Wilson addressed labor issues by advocating for the Keating–Owen Child Labor Act (1916), which was later struck down by the Supreme Court, and pushing for an eight-hour workday for railroad workers. He also signed the Federal Farm Loan Act, which provided low-interest loans to farmers, securing his political support in rural areas.

Territorial and Immigration Policies

Woodrow Wilson continued efforts toward Philippine independence with the Jones Act of 1916 and purchased the Danish West Indies (now U.S. Virgin Islands) in the same year. He vetoed two bills aimed at restricting immigration from southern and eastern Europe, reflecting his relatively favorable stance toward new immigrants, though Congress overrode one of his vetoes.

Judicial Appointments

Woodrow Wilson nominated three Supreme Court justices, including Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, whose confirmation sparked controversy but who became a leading progressive voice on the court.

Foreign Policy and Latin America

Woodrow Wilson foreign policy focused on a rejection of imperialism, though he frequently intervened in Latin American countries, such as Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. His handling of the Mexican Revolution and relations with leaders like Pancho Villa and Venustiano Carranza was complicated, culminating in a military expedition to capture Villa after a raid on U.S. soil.

World War I Neutrality

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 saw Woodrow Wilson steadfastly maintaining U.S. neutrality, despite pressures from both interventionists and pacifists. He navigated crises such as the sinking of the Lusitania and German submarine warfare, demanding accountability from Germany while avoiding immediate war. His preparedness movement, including expanding the army and navy, was a precursor to the U.S.’s eventual involvement in the war.

Personal Life and Remarriage

Woodrow Wilson faced personal tragedy with the death of his first wife, Ellen, in 1914. A year later, he met and married Edith Bolling Galt, who would later play a significant role in his second term, particularly after his health declined following a stroke.

Woodrow Wilson presidency was transformative for the U.S., with his domestic reforms reshaping the economy and his foreign policy setting the stage for America’s involvement in World War I. His leadership style, willingness to confront entrenched interests, and progressive legislative achievements left a lasting legacy.

The presidential election of 1916

was significant in shaping both domestic and foreign policies for the United States during a critical era of world history. Incumbent President Woodrow Wilson, running for re-election, was renominated by the Democratic Party without opposition, while the Republicans selected Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes as their candidate. Woodrow Wilson campaign emphasized progressive reforms such as the eight-hour workday, the prohibition of child labor, and protections for female workers. His administration also advocated for a minimum wage for federal workers. The Democrats campaigned under the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War,” leveraging Wilson’s success in maintaining American neutrality during the early years of World War I.

The election was incredibly close, with the result hinging on the state of California. Woodrow Wilson ultimately won by a narrow margin of 3,806 votes in California, securing 277 electoral votes to Hughes’ 254. Wilson’s victory made him the first Democratic president since Andrew Jackson to win two consecutive terms. His win was largely attributed to support from progressive voters and Western states, which offset Hughes’ dominance in the Northeast and Midwest.

Shortly after his re-election, Woodrow Wilson administration faced a critical shift in foreign policy. In January 1917, Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, targeting all ships, including those of neutral nations like the United States. The release of the Zimmermann Telegram, in which Germany attempted to ally with Mexico against the U.S., further inflamed American sentiment. Following attacks on U.S. ships, Wilson convened his Cabinet, which unanimously agreed to a declaration of war.

On April 2, 1917, Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, asserting that the world must be made “safe for democracy.” Congress approved the declaration on April 6, leading to U.S. involvement in World War I. Wilson oversaw the rapid expansion of the U.S. military, including the implementation of the Selective Service Act of 1917, which drafted millions of soldiers. By mid-1918, the U.S. was deploying thousands of troops daily to Europe, significantly bolstering the Allied war effort.

Woodrow Wilson vision for the post-war world was articulated in his famous “Fourteen Points” speech in January 1918, in which he outlined principles for lasting peace, including the creation of an international organization to prevent future conflicts—what would become the League of Nations. Although the U.S. played a key role in the final victory of the Allied Powers, with Germany surrendering in November 1918, Wilson’s efforts to shape the peace proved contentious both at home and abroad. The Treaty of Versailles, negotiated in 1919, included many of Wilson’s ideals but also imposed harsh penalties on Germany, sowing seeds of future conflict.

Woodrow Wilson leadership during the war and his vision for peace earned him the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize, although his health deteriorated, and he faced opposition from Congress over U.S. involvement in the League of Nations. Nonetheless, the 1916 election and its aftermath were pivotal moments in both American history and the broader global landscape of the early 20th century.

Ratification debate and defeat

The debate surrounding the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations revealed deep divisions within the U.S. Senate and broader American society about the nation’s role in global affairs. After Woodrow Wilson returned from the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919, the treaty required Senate approval with a two-thirds majority, a challenging prospect given the Republicans’ narrow control of the chamber. Many Republicans, led by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, pushed for changes to the treaty, especially regarding Article X, which required members of the League of Nations to defend each other against external aggression. This provision caused great concern about the potential loss of U.S. sovereignty.

The senators fell into three groups: those who supported the treaty, the “irreconcilables” who opposed any involvement in the League, and the “reservationists” who would support the treaty with modifications. Despite some efforts to broker a compromise, Woodrow Wilson refusal to accept any changes to the treaty led to its defeat in the Senate in March 1920.

Woodrow Wilson deteriorating health further complicated the ratification debate. In September 1919, during a tour to rally public support for the treaty, Wilson suffered a stroke, leaving him severely debilitated. His incapacity was largely concealed by his inner circle, including his wife Edith, who took on a more prominent role in managing presidential affairs. Despite growing public knowledge of his condition by early 1920, Wilson continued to resist any compromise on the treaty, and the final vote fell short of the necessary two-thirds majority.

Meanwhile, domestic issues intensified. Demobilization after World War I was chaotic, leading to strikes, race riots, and a severe economic downturn. The “Red Scare” heightened fears of radicalism, and Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s raids on suspected radicals, including anarchists, further stoked public anxiety.

Despite these challenges, some progress occurred. The 18th Amendment, which established Prohibition, took effect in 1919, although Woodrow Wilson vetoed the enforcement legislation. Wilson also supported the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote, marking a significant victory for the suffrage movement.

As the 1920 presidential election approached, Wilson, though eager to seek a third term, was too ill to campaign actively. The Democrats nominated James M. Cox and Franklin D. Roosevelt, while the Republicans, led by Warren G. Harding, ran on a platform of returning to “normalcy” after the turmoil of Wilson’s presidency. Harding won in a landslide, signaling a shift away from Wilson’s progressive internationalism.

Final years and death (1921–1924)

Woodrow Wilson post-presidency years were marked by declining health and a failed attempt at practicing law. He remained politically active from the sidelines but passed away on February 3, 1924. Wilson’s legacy, particularly his role in founding the League of Nations, earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1920, though his vision of U.S. leadership in global affairs was ultimately rejected by his own country. His final resting place in Washington National Cathedral symbolizes his enduring, yet controversial, impact on American history.

Woodrow Wilson’s approach to race relations reflected deeply rooted biases and reinforced racial segregation across various sectors during his presidency. Born in the South to pro-slavery parents, Wilson was steeped in the Lost Cause mythology and slavery apologism, which profoundly shaped his policies and views. His administration, marked by racial segregation in federal offices and discriminatory practices in military and employment sectors, fueled racial inequalities and tensions that reverberated throughout the country.

Segregation in Federal Offices

Woodrow Wilson presidency significantly escalated racial segregation within the federal government. Although segregation had begun under earlier administrations, Wilson’s policies took it to new levels. In 1913, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson advocated for segregating government offices, and while Wilson didn’t mandate it, he allowed Cabinet Secretaries the discretion to impose segregation in their departments. By the end of the year, major government agencies like the Treasury, Post Office, and Navy had segregated workspaces, restrooms, and cafeterias. These policies excluded African Americans from meaningful career opportunities, as many agencies began using segregation as an excuse to implement whites-only hiring practices.

The introduction of a new hiring policy in 1914 requiring job applicants to submit a photograph further enabled racial discrimination, effectively barring African Americans from entering the federal workforce. This resulted in widespread disenfranchisement for black workers, many of whom were fired or forced into early retirement. For African Americans, federal employment had long been a path toward stability and social mobility, but under Wilson, these opportunities were systematically erased, worsening the economic plight of African Americans in Washington, D.C., and beyond.

African Americans in the Armed Forces

Woodrow Wilson racial policies extended into the U.S. military, where segregation became more pronounced during his tenure. Black soldiers were often confined to segregated units led by white officers, and the military refused to commission new black officers. While black soldiers were drafted equally during World War I, their service was marred by discrimination. In the Navy, Wilson’s appointee, Josephus Daniels, implemented a system of Jim Crow that relegated African American sailors to menial tasks, further entrenching racial hierarchies within the military.

Response to Racial Violence

The Great Migration during Woodrow Wilson presidency led to significant racial tensions, as African Americans moved north in search of better economic opportunities. This migration sparked a wave of violent race riots, most notably the East St. Louis riots in 1917. Wilson’s response to these events was tepid at best, as he only considered federal intervention after public pressure but took no direct action.

Although Woodrow Wilson condemned lynching in 1918, his administration did little to curb racial violence. When a fresh wave of race riots erupted in 1919, in cities like Chicago and Omaha, the federal government remained passive, offering no support to quell the violence. This lack of action cemented the view that Wilson’s administration, while occasionally paying lip service to racial justice, largely perpetuated racial inequality and allowed racially motivated violence to continue unchecked.

Legacy and Impact

Woodrow Wilson legacy on race relations is one of regression, characterized by an increased entrenchment of segregation and systemic discrimination in federal employment, military service, and the general treatment of African Americans. His actions — or inactions — regarding racial violence and segregation starkly contrast with his advocacy for democracy on the world stage, leaving behind a presidency that reinforced the racial divide in America for decades to come.

Woodrow Wilson’s legacy is complex, marked by significant achievements in domestic policy and international relations, yet deeply tarnished by his racial policies and the segregation he enforced during his presidency. While historians generally regard him as an above-average president, his reputation varies widely based on the aspect of his presidency being considered.

Historical Reputation

Woodrow Wilson is credited with laying the groundwork for modern American liberalism and expanding the role of the federal government to protect citizens from the influence of large corporations. His administration established significant reforms, such as the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Trade Commission, and the graduated income tax, which have had lasting impacts on American governance. His ambitious domestic agenda is often compared to the New Deal and the Great Society in terms of its scope and influence.

However, Woodrow Wilson expansion of federal power has drawn criticism from conservatives who view him as a progenitor of an “imperial presidency”. His foreign policy, characterized by idealism and the promotion of democracy worldwide—often referred to as “Wilsonianism”—set a precedent for American engagement in global affairs, influencing future international organizations like the United Nations.

Despite these accomplishments, Woodrow Wilson legacy is heavily scrutinized due to his appalling record on race relations and civil liberties. Many African Americans who initially supported him felt betrayed by his policies that enforced racial segregation in federal offices. While he garnered support from the African American community in his election, his administration’s imposition of Jim Crow practices led to significant disillusionment. Historians argue that Wilson’s acceptance of segregation was partly a political strategy to avoid social upheaval, leading to an increase in discrimination and diminishing opportunities for black civil servants.

Memorials and Commemorations

Woodrow Wilson legacy is memorialized in various ways across the United States and internationally. Notable sites include the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library in Staunton, Virginia, and his childhood home in Augusta, Georgia, which are recognized as National Historic Landmarks. Additionally, institutions like the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., and schools and streets named after him commemorate his contributions to public policy and international relations.

However, recent years have seen a reevaluation of Woodrow Wilson legacy, particularly in light of his segregationist policies. In 2020, Princeton University decided to remove Wilson’s name from its School of Public and International Affairs due to his “racist attitudes and policies,” reflecting a growing movement to reconsider how historical figures are honored.

Popular Culture

Woodrow Wilson life and presidency have also been depicted in popular culture, most notably in the 1944 biopic Woodrow Wilson, directed by Henry King. The film, starring Alexander Knox, received critical acclaim and numerous Academy Award nominations, showcasing an idealistic portrayal of Wilson. However, despite its accolades, the film was a box-office failure, reflecting the complexities and challenges of portraying Wilson’s multifaceted legacy.

Conclusion

Woodrow Wilson’s legacy is a study in contrasts. While he is remembered for significant advancements in federal policy and international diplomacy, his presidency is equally marked by regressive racial policies that had long-lasting negative effects on African Americans. This duality continues to provoke debate among historians, political scientists, and the public as they grapple with the complexities of his impact on American society and governance. As the nation reflects on its history, Woodrow Wilson serves as a poignant example of how individual legacies can be both impactful and problematic, prompting a reevaluation of how we remember and honor past leaders.