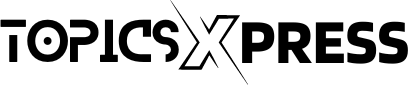

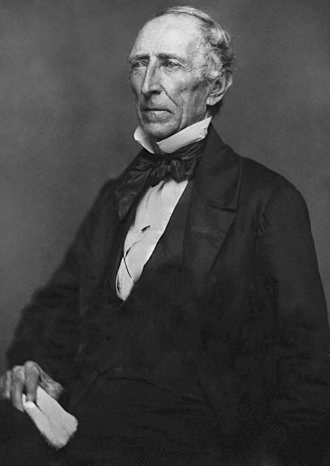

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was a prominent American politician and lawyer who served as the tenth President of the United States from 1841 to 1845. He began his political career as the tenth Vice President in 1841, succeeding to the presidency after the untimely death of President William Henry Harrison just 31 days into office.

Tyler’s presidency was marked by his staunch advocacy for states’ rights, particularly concerning slavery. He aligned with the Whig Party but often clashed with its leadership, including Henry Clay, over matters of policy and presidential authority. Despite his unexpected rise to the presidency, Tyler faced considerable opposition from both major political parties during his tenure.

Born into a prominent Virginia family with ties to slavery, Tyler’s political journey saw him evolve from a Democrat critical of President Andrew Jackson to a Whig ally and eventually, President. His presidency was notable for signing significant legislation and treaties, including the Webster–Ashburton Treaty with Britain and the Treaty of Wanghia with China. Tyler also championed the annexation of Texas, viewing it as a strategic move for U.S. expansion.

Following his presidency, Tyler’s political allegiances shifted again during the onset of the Civil War. Initially supporting efforts for peace, he later aligned with the Confederacy, serving in its provisional government until his death.

While Tyler’s presidency has received mixed historical assessments, his contributions to American foreign policy and expansionist ideals remain noteworthy. Today, his legacy endures as a testament to the complexities of 19th-century American politics and the challenges of presidential leadership.

Early Life and Education of John Tyler’s

John Tyler was born on March 29, 1790, at Greenway Plantation in Charles City County, Virginia, into a prominent family of English descent. His father, John Tyler Sr., was a planter and judge, and his mother, Mary Armistead Tyler, came from a wealthy Virginia family. Growing up on his family’s plantation, Tyler received a classical education typical of the southern gentry, attending local private schools.

In 1807, Tyler enrolled at the College of William and Mary, where he studied law. During his time at the college, he became interested in politics and joined the prestigious literary and debating society, the Philomathean Society. He graduated from William and Mary in 1807 and was admitted to the Virginia bar shortly thereafter, beginning his legal career in Richmond.

Tyler’s education and early experiences in Virginia’s social and political circles shaped his worldview, particularly his staunch advocacy for states’ rights. Influenced by Virginia’s tradition of states’ sovereignty and his family’s political connections, Tyler quickly rose in prominence as a young lawyer and politician. His early legal career laid the groundwork for his later political successes and his eventual presidency.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

Planter and lawyer

John Tyler’s legal career began unusually early when he was admitted to the Virginia bar at just 19 years old, although the judge who admitted him overlooked his age requirement. At the time, his father held the position of governor of Virginia, providing Tyler with a significant entry into Richmond’s legal circles, the state capital.

By 1810, records from the federal census show that a “John Tyler” (likely his father) owned eight enslaved individuals in Richmond. Additional records suggest he owned possibly five more in neighboring Henrico County and as many as 26 in Charles City County.

In 1813, following his father’s death, John Tyler Jr. purchased Woodburn plantation, where he resided until 1821. By the 1820 census, Tyler owned 24 enslaved individuals at Woodburn, having inherited 13 from his father. However, only eight were reported as actively engaged in agricultural work at that time.

Political rise

Start in Virginia politics

In 1811, John Tyler, then 21 years old, embarked on his political career by winning election to represent Charles City County in the Virginia House of Delegates. Over five consecutive terms, Tyler served alongside prominent figures like Cornelius Egmon and later Benjamin Harrison. His tenure on the Courts and Justice Committee highlighted his firm stances on states’ rights and his vocal opposition to the establishment of a national bank.

Tyler’s early legislative record showcased his alignment with fellow legislator Benjamin W. Leigh in advocating for the censure of Virginia’s U.S. Senators William Branch Giles and Richard Brent. This action was spurred by their votes in favor of rechartering the First Bank of the United States, contrary to the directives of the Virginia legislature.

Tyler’s Stance on the War of 1812 and Early Military Service

Like many Americans of his era, John Tyler harbored strong anti-British sentiments. When the War of 1812 broke out, he passionately advocated for military action in a speech to the Virginia House of Delegates. In response to the British capture of Hampton, Virginia, in the summer of 1813, Tyler took decisive action by organizing the Charles City Rifles, a militia company dedicated to defending Richmond. He assumed the role of captain but disbanded the company two months later when no attack materialized.

For his brief military service, Tyler was granted land near what would later become Sioux City, Iowa, as recognition of his efforts.

In 1813, following his father’s death, Tyler inherited 13 slaves along with his father’s plantation. Three years later, in 1816, he resigned from the House of Delegates to join the Governor’s Council of State. This council, comprising eight elected advisers, provided Tyler with a pivotal role in shaping Virginia’s governance and policies.

U.S. House of Representatives

Following the death of U.S. Representative John Clopton in September 1816, John Tyler seized the opportunity to enter national politics, competing against his friend and ally Andrew Stevenson for Virginia’s 23rd congressional district. Tyler’s successful campaign, heavily reliant on his political connections and persuasive campaigning skills, secured him a seat in the Fourteenth Congress. He was sworn in on December 17, 1816, as a Democratic-Republican, aligning himself with the predominant political party of the Era of Good Feelings.

Tyler’s tenure in Congress was marked by his steadfast adherence to strict constructionist principles. He vehemently opposed federal funding for internal improvements such as ports and roads, arguing that such projects should be financed and managed by individual states using local resources. This stance reflected his deep-seated belief in states’ rights and limited federal authority.

In 1818, Tyler’s role on a committee auditing the Second Bank of the United States exposed him to what he perceived as widespread corruption within the institution. He advocated strongly for the bank’s charter revocation, but his proposal faced staunch opposition in Congress.

Tyler’s tenure also saw him clash with figures like General Andrew Jackson over military actions and banking policies. Despite his admiration for Jackson’s character, Tyler criticized what he saw as Jackson’s overzealous actions during the First Seminole War, particularly the execution of two British subjects without trial.

One of the defining issues of the Sixteenth Congress (1819–1821) was the admission of Missouri to the Union and the contentious debate over slavery’s expansion into new territories. Tyler opposed the Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state while restricting slavery in territories north of Missouri’s southern border. His opposition stemmed from his belief that Congress lacked the constitutional authority to regulate slavery and that the compromise would exacerbate sectional tensions.

In late 1820, citing health concerns and disillusionment with congressional effectiveness, Tyler decided not to seek re-election. He returned to private law practice, focusing on his family and professional pursuits. Despite his short tenure, Tyler’s principled stance on states’ rights and limited government intervention left a lasting impact on the political landscape of his era.

Return to state politics

Political Rise and Governorship of John Tyler

Restless after two years of practicing law at home, John Tyler sought election to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1823. With neither incumbent from Charles City County seeking reelection, Tyler easily won a seat that April, finishing first among the three candidates vying for the two available seats.

Upon convening in December, Tyler found the House of Delegates embroiled in debates over the upcoming presidential election of 1824. He championed the congressional nominating caucus system, advocating for William H. Crawford as the Democratic-Republican candidate. Although Crawford gained legislative support, Tyler’s proposal ultimately failed. However, Tyler’s lasting impact during this term was his successful effort to save the College of William and Mary from closure due to declining enrollment. Instead of relocating the college from rural Williamsburg to Richmond, Tyler proposed and implemented administrative and financial reforms that revitalized the institution, leading to a surge in enrollment by 1840.

Tyler’s political stature continued to rise, positioning him as a potential candidate for the U.S. Senate in 1824. Ultimately, in December 1825, he was nominated and elected as the governor of Virginia by the legislature, defeating John Floyd with a vote of 131 to 81. During his governorship under the limited powers granted by the original Virginia Constitution (1776–1830), Tyler lacked veto authority but utilized his oratorical skills effectively. His most notable act as governor was delivering a stirring funeral address for Thomas Jefferson, who had passed away on July 4, 1826. Tyler, deeply admiring Jefferson, delivered a eulogy that resonated widely.

Governor Tyler’s tenure was marked by his staunch advocacy for states’ rights and opposition to federal encroachments. He proposed expanding Virginia’s road system to counter federal infrastructure plans and briefly considered enhancing the state’s underfunded public school system, although significant reforms did not materialize.

In December 1826, Tyler was unanimously reelected to a second one-year term as governor. His influence continued to grow, leading to his election as a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830. Serving alongside notable figures such as Chief Justice John Marshall, Tyler played a key role on the Committee on the Legislature, contributing to discussions on state governance and constitutional reform.

Throughout his state-level service, Tyler’s commitment to Virginia’s interests remained steadfast, evidenced by his roles as president of the Virginia Colonization Society and later as rector and chancellor of the College of William and Mary.

U.S. Senate

In January 1827, the Virginia General Assembly deliberated on whether to re-elect U.S. Senator John Randolph to a full six-year term. Randolph, known for his strong states’ rights stance shared by many in the legislature, also garnered notoriety for his impassioned speeches and unpredictable behavior in the Senate. His vehement opposition to President John Quincy Adams and Senator Henry Clay had alienated him from some colleagues.

Facing a divided assembly, nationalists within the Democratic-Republican Party sought to replace Randolph with someone more aligned with their views. They approached John Tyler, hoping to sway states’ rights supporters uncomfortable with Randolph’s controversial reputation. Despite initial refusals, Tyler eventually yielded to mounting political pressure and agreed to stand for election. On voting day, arguments centered on Tyler being a more conciliatory choice compared to Randolph, with concerns raised that Tyler’s election might indirectly support the Adams administration.

In a closely contested vote of 115–110, Tyler was elected, prompting his resignation as governor on March 4, 1827, to begin his Senate term.

Democratic maverick

During Tyler’s senatorial election in the midst of the 1828 presidential campaign, incumbent President Adams faced a formidable challenge from Andrew Jackson. The Democratic-Republican Party fractured into Adams’s National Republicans and Jackson’s Democrats. Tyler found himself disenchanted with both candidates, wary of their inclinations to expand federal authority. Yet, he leaned towards Jackson, hoping the latter would restrain federal spending on internal improvements unlike Adams. Reflecting on Jackson, Tyler expressed, “Turning to him I may at least indulge in hope; looking on Adams I must despair.”

When the Twentieth Congress convened in December 1827, Tyler collaborated closely with his Virginia colleague, Littleton Waller Tazewell, who shared his strict interpretation of the Constitution and reserved support for Jackson. Throughout his tenure, Tyler vehemently opposed federal infrastructure projects, arguing these should be within the purview of individual states. He and fellow Southerners unsuccessfully fought against the protectionist Tariff of 1828, derisively dubbed the “Tariff of Abominations”. Tyler foresaw the tariff sparking national backlash and undermining states’ rights, a cause he staunchly defended. He asserted, “they may strike the Federal Government out of existence by a word; demolish the Constitution and scatter its fragments to the winds.”

Tyler soon clashed with President Jackson over the burgeoning spoils system, which he criticized as a tool for political gain. He regularly opposed Jackson’s nominations that seemed unconstitutional or driven by patronage, actions deemed rebellious within his own party. Particularly aggrieved by Jackson’s recess appointments to negotiate with the Ottoman Empire, Tyler introduced a bill censuring the President for overstepping his authority.

Despite their disagreements, Tyler occasionally aligned with Jackson, supporting his veto of the Maysville Road funding deemed unconstitutional. He also backed several of Jackson’s appointments, including Martin Van Buren as Minister to Britain. The pivotal issue of the 1832 presidential election centered on the recharter of the Second Bank of the United States, which both Tyler and Jackson opposed. When Congress voted to renew the bank’s charter in July 1832, Jackson vetoed the bill on constitutional grounds, a decision Tyler supported. He endorsed Jackson’s successful reelection bid, despite their ongoing policy divergences.

Break with the Democratic Party

Tyler’s Struggle with Party Loyalties during the Nullification Crisis

During the 22nd Congress, the Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833 thrust John Tyler into a pivotal role. South Carolina, aggrieved by the “Tariff of Abominations,” passed the Ordinance of Nullification in November 1832, asserting its right to reject federal laws. President Jackson’s readiness to enforce the tariff with military might clashed with Tyler’s sympathy for South Carolina’s position. In February 1833, Tyler delivered a speech opposing Jackson’s use of force, advocating instead for Henry Clay’s Compromise Tariff to ease tensions.

Tyler’s stance cost him support from the pro-Jackson faction in Virginia, jeopardizing his reelection in February 1833 against Democrat James McDowell. However, Clay’s endorsement helped Tyler secure another term, albeit narrowly.

Further straining relations with Jackson, Tyler condemned the President’s unilateral action to dismantle the Bank of the United States in September 1833. Viewing it as an abuse of power, Tyler aligned himself with Jackson’s opponents and voted for censure resolutions in the Senate in March 1834. This marked Tyler’s formal affiliation with Clay’s Whig Party, which granted him the honor of serving as President pro tempore of the Senate in March 1835, making him the only U.S. president to hold this position.

Despite his growing alignment with the Whigs, Tyler faced pressure from the Democratic-controlled Virginia House of Delegates to vote against his principles on Jackson’s censure. In February 1836, after much deliberation and conflicting advice from friends, Tyler resigned from the Senate, maintaining his steadfast commitment to honor and principle in public office.

1836 presidential election

In the 1836 presidential election, John Tyler found himself at a political crossroads. Having resigned from the U.S. Senate earlier that year due to conflicts with President Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party, Tyler’s alignment with the Whig Party was solidifying. The election was pivotal, with Martin Van Buren nominated by the Democrats and the Whigs fielding multiple candidates in different regions to challenge him.

Tyler, though not a presidential candidate himself, played a crucial role in the Whig strategy. The party hoped to capitalize on dissatisfaction with Jackson’s policies, including his handling of the Bank of the United States and his stance on tariffs. Tyler’s stature as a former senator and his alignment with Henry Clay’s Whig faction lent credibility to the Whig cause.

Ultimately, Martin Van Buren won the election, succeeding Andrew Jackson as President. Tyler’s decision to resign from the Senate and his growing affiliation with the Whig Party set the stage for his own future political ambitions, culminating in his unexpected presidency after William Henry Harrison’s untimely death in 1841. The 1836 election marked a transitional phase for Tyler, solidifying his role within the evolving political landscape of the United States.

National political figure

In his role as a U.S. senator, John Tyler became increasingly involved in Virginia politics, particularly during his tenure from October 1829 to January 1830 as a member of the state constitutional convention. Initially hesitant to accept the position, Tyler found himself navigating the complex dynamics of Virginia’s political landscape. The convention was pivotal in reshaping Virginia’s governance, addressing issues such as the disproportionate influence of the state’s eastern counties, which favored conservative policies and maintained strict suffrage qualifications tied to property ownership.

As a slaveowner from eastern Virginia, Tyler generally supported maintaining the status quo but opted to remain neutral during much of the convention debates. His strategic approach aimed to avoid alienating any faction within the state while focusing on maintaining a broad base of support for his Senate career. Tyler advocated for compromise and unity in his speeches, emphasizing the importance of accommodating both the conservative eastern counties and the more populous and liberal western counties seeking expanded influence.

Following the 1836 election, where Tyler had initially planned to retire from politics, he found himself drawn back into public service. In 1838, he successfully campaigned for a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, marking his third term as a delegate. By this time, Tyler had gained national recognition, and his return to state politics allowed him to address significant national issues, including debates over the sale of public lands.

Meanwhile, Tyler’s successor in the U.S. Senate, William Cabell Rives, presented a dilemma for the Virginia General Assembly in February 1839. Rives, once a Democrat, had drifted away from his party, potentially aligning himself with the Whigs. With Rives’ seat up for grabs and the Whigs divided in their support between Rives and Tyler, the Senate seat remained vacant for nearly two years amidst political maneuvering, reflecting the shifting alliances and strategies leading up to the 1840 presidential election.

1840 presidential election

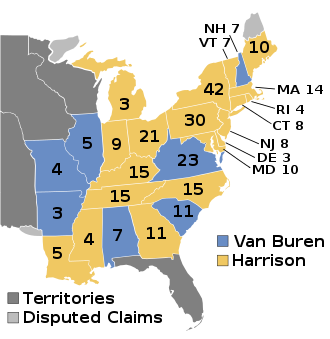

The 1840 presidential election marked a significant moment in American political history, characterized by high stakes and vigorous campaigning. The Whig Party, emerging as a major opposition force to the Democrats, sought to unseat Democratic incumbent Martin Van Buren, who had succeeded Andrew Jackson as president. The Whigs nominated General William Henry Harrison, a war hero and former governor of the Indiana Territory, as their presidential candidate. Harrison’s running mate was John Tyler, who brought southern support and credibility to the ticket.

The election campaign was marked by innovative tactics, including extensive use of slogans, symbols, and mass rallies to mobilize voters. The Whigs portrayed Harrison as a man of the people, contrasting him with the aristocratic Van Buren. Harrison’s military background, particularly his role in the Battle of Tippecanoe, was emphasized to appeal to voters’ patriotic sentiments.

The Democrats, led by Van Buren, faced challenges due to economic downturns and public discontent, which the Whigs capitalized on. “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” became the rallying cry for the Whig campaign, highlighting Harrison’s military exploits and Tyler’s southern appeal. This slogan resonated with voters across the country, contributing to the Whig victory.

Ultimately, the 1840 election saw a significant voter turnout, with the Whigs successfully painting Van Buren as out of touch with the economic hardships facing ordinary Americans. Harrison won the presidency, becoming the first Whig candidate to achieve this feat. John Tyler’s role as vice president-elect set the stage for his unexpected ascension to the presidency following Harrison’s untimely death just a month into his term, altering the course of American political history.

Adding Tyler to the ticket

At the 1839 Whig National Convention in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the United States was grappling with a severe recession spurred by the Panic of 1837. President Van Buren’s handling of the economic downturn had eroded public confidence in the Democratic Party, setting the stage for a competitive election. Candidates such as William Henry Harrison, Henry Clay, and General Winfield Scott vied for the Whig presidential nomination. Tyler, although part of the Virginia delegation, had no official role due to lingering tensions from his unresolved Senate bid.

The convention saw a deadlock among the frontrunners, with Virginia initially supporting Clay. However, Northern Whig opposition to Clay, coupled with revelations about Scott’s perceived abolitionist sympathies, shifted Virginia’s support to Harrison. This pivotal move secured Harrison the presidential nomination, amid lesser attention given to the vice presidential slot.

Tyler’s selection as vice president was somewhat incidental. As a Southern slaveowner, he balanced the ticket and assuaged concerns among Southern Whigs about potential abolitionist sentiments within the party. While some speculated Tyler’s nomination was a result of pragmatic choices rather than enthusiastic endorsement, his candidacy aimed to secure crucial Southern votes, particularly from Virginia.

Following his unexpected ascension to the presidency after Harrison’s untimely death, Tyler faced criticism for allegedly concealing his political views during the convention. His presidency began amidst skepticism and tensions with the Whig Party, leading to a contentious relationship that ultimately shaped his political legacy.

General election

The Whig Party in the 1840 election opted not to create a formal platform, fearing internal division. Instead, they focused their campaign on criticizing Van Buren and the Democrats for the economic downturn. Tyler received praise for his principled resignation over state legislative instructions. Initially, the Whigs tried to limit Harrison’s and Tyler’s policy statements to avoid alienating different party factions. However, Tyler’s involvement grew as he addressed Northern concerns alongside Harrison at various rallies and conventions, navigating questions and sometimes deflecting them with references to Harrison’s broad positions.

The Whigs embarked on an unprecedented national campaign, mobilizing supporters across the country, including women, despite their inability to vote at the time. This marked the first large-scale involvement of women in American political campaigns. Events such as torchlight processions and spirited rallies fueled public enthusiasm. The famous “log cabin and hard cider” imagery, contrasting with Harrison’s actual wealth and Tyler’s status, became a centerpiece of their campaign. Cider, a common drink among the populace, was portrayed as Harrison’s preference, furthering his appeal as a man of the people.

The election strategy emphasized Harrison’s military background, epitomized in the popular campaign song “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too”, celebrating Harrison’s victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe. Glee clubs across the nation rallied around patriotic songs in support of the Whig Party. Despite personal disappointments, such as Clay’s continuing electoral defeats, Tyler’s withdrawal from a Senate race ensured alignment with Whig objectives, including a successful campaign in Virginia.

The election results saw Harrison and Tyler secure a significant victory with 234 electoral votes to Van Buren’s 60, alongside 53% of the popular vote. The Whigs also gained control of both houses of Congress, solidifying their political ascendancy following a contentious and dynamic campaign season.

Vice Presidency (1841)

As vice president-elect, Tyler remained quietly at his home in Williamsburg, hoping for a decisive presidency from Harrison and avoiding involvement in Cabinet selections or federal appointments. Despite Clay’s pressure and the influx of office seekers, Harrison sought Tyler’s counsel on dismissing Van Buren appointees, respecting Tyler’s advice against removal.

Tyler was sworn in on March 4, 1841, delivering a brief speech on states’ rights in the Senate chamber before attending Harrison’s inauguration. Following Harrison’s lengthy inaugural address and overseeing Cabinet confirmations the next day, Tyler anticipated a quiet role and returned home to Williamsburg.

Had Harrison lived, Tyler might have remained obscure, but Harrison’s rapid decline from pneumonia elevated Tyler unexpectedly. Alerted to Harrison’s deteriorating health, Tyler received official news of Harrison’s death on April 5, 1841, prompting his immediate journey to Washington.

Presidency (1841–1845)

Upon assuming office following Harrison’s unprecedented death, Tyler faced constitutional uncertainty over presidential succession. Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the U.S. Constitution provided guidelines, but interpretation was crucial: did Tyler inherit the title or merely its powers?

The Cabinet quickly convened and initially termed Tyler “vice-president acting president,” but Tyler asserted his right to full presidential powers. He was promptly sworn in by Judge William Cranch, becoming the youngest president at 51, setting a precedent for seamless transitions later codified by the 25th Amendment.

Despite retaining Harrison’s cabinet to appease his supporters, Tyler clashed with them on policy. He asserted his independence at his first cabinet meeting, rejecting any notion of being dictated to and affirming his accountability for his administration.

Tyler’s informal inaugural address to Congress underscored his commitment to Jeffersonian democracy and limited federal authority, but not all accepted his presidency. Opponents like John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay contested Tyler’s claim, viewing him as an interim caretaker rather than a full-fledged president.

Ultimately, Congress ratified Tyler’s presidency through a joint resolution on May 31, 1841, solidifying his position. Despite enduring mockery and opposition throughout his term, Tyler steadfastly maintained his legitimacy and presidential authority, even returning correspondence addressed to him incorrectly.

Tyler’s tenure as president marked by decisive leadership at the outset, despite his belief in restrained presidential powers favoring legislative initiative over executive dominance.

Economic Policy and Party Conflicts

John Tyler’s presidency was marked by significant clashes with the Whig Party, particularly over economic policies and the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches. Initially aligned with Whig Congress’s agenda, Tyler signed key bills into law, including the preemption bill granting settlers rights on public land, a Distribution Act, a new bankruptcy law, and the repeal of the Independent Treasury.

However, tensions arose when it came to banking legislation. Tyler opposed Clay’s proposals for a national banking act and vetoed them twice, despite modifications aimed at addressing his concerns. This defiance, seen as protecting Clay’s political aspirations by ensuring Tyler’s unpopularity, coined the term “heading Captain Tyler.”

The breaking point came after Tyler’s second bank veto on September 11, 1841, when most of his cabinet resigned under pressure orchestrated by Clay. Only Daniel Webster remained to finalize the Webster–Ashburton Treaty and demonstrate independence from Clay’s control. Despite threats and ostracization from the Whig Party, Tyler stood firm, refusing to resign or yield to Clay’s maneuvers.

Tyler’s stance led to his expulsion from the Whig Party by Congress, accompanied by harsh criticism in Whig newspapers and even threats to his life. The White House itself fell into disrepair as a symbol of the party’s disdain for Tyler’s presidency.

Despite these challenges, Tyler persisted in promoting his own fiscal plans, such as the “Exchequer,” though these were largely ignored by the Whig-dominated Congress. His presidency exemplified the struggles between executive authority and legislative dominance during a period of intense party polarization.

Tariff and Distribution Debate

In mid-1841, facing an $11 million budget deficit, the Tyler administration confronted the pressing need for higher tariffs while adhering to the 20% rate set by the 1833 Compromise Tariff. Tyler also supported distributing revenue from public land sales to states, despite its impact on federal revenue, to aid states burdened by debt. This initiative aimed to strike a balance between fiscal responsibility and economic relief.

The Whigs, advocating high protectionist tariffs and federal funding for state infrastructure, found common ground with Tyler on tariff policies. The Distribution Act of 1841 was enacted, implementing a distribution program alongside a tariff ceiling at 20%. Subsequently, tariffs were raised to this level on previously low-taxed goods. However, by March 1842, it became evident that these measures were insufficient to alleviate the federal government’s financial woes.

The underlying economic crisis, stemming from the Panic of 1837 and exacerbated by subsequent financial collapses, deepened the nation’s divisions. Northern states favored protective tariffs to shield their burgeoning industries, while Southern states, reliant on agricultural exports like cotton, opposed tariffs that hindered trade with Britain.

Tyler, acknowledging the fiscal imperative, recommended overriding the 1833 Compromise Tariff to increase rates beyond 20%. This move would suspend the distribution program, redirecting all revenues to federal coffers. Despite Tyler’s plea, the Whig-controlled Congress remained steadfast in their support for maintaining the distribution of funds to states.

In June 1842, Congress passed two bills to raise tariffs and extend the distribution program without conditions. Tyler, deeming it inappropriate to continue distribution amid fiscal shortfall, vetoed both bills, severing ties with the Whigs. Congress’s subsequent attempt to consolidate these bills into one also met Tyler’s veto, which Congress failed to override.

Ultimately, facing the necessity of action, Congress, led by Millard Fillmore, passed the Tariff of 1842 to restore tariffs to 1832 levels and abolish the distribution program. Tyler signed this bill on August 30, 1842, effectively ending the contentious debate over tariffs and distribution during his presidency.

New York Customs House Reform

In May 1841, President Tyler took decisive action against alleged fraud at the New York Customs House, appointing a commission led by George Poindexter, a former governor and U.S. Senator from Mississippi. This commission was tasked with investigating misconduct that occurred during Martin Van Buren’s presidency, particularly under the tenure of Jesse D. Hoyt, the New York Collector.

The Poindexter Commission’s investigation unearthed significant fraudulent activities, implicating Hoyt and causing a stir within the Whig-controlled Congress. Members of Congress demanded access to the commission’s findings and criticized Tyler for authorizing expenditures on the investigation without their approval. In response, Tyler defended his actions as a fulfillment of his constitutional duty to uphold the law.

Upon the completion of the investigation on April 29, 1842, the House requested the report, which Tyler promptly provided. Poindexter’s findings proved damning for the Whig-appointed New York Collector, Jesse D. Hoyt, highlighting irregularities that embarrassed the Whig establishment.

In a move to curtail Tyler’s unilateral actions, Congress swiftly passed an appropriations law prohibiting the president from allocating funds to investigations without Congressional consent. This legislative response reflected ongoing tensions between Tyler and the Whig-controlled Congress over executive authority and fiscal oversight.

House Petition of Impeachment

Shortly after Tyler’s contentious tariff vetoes, Whigs in the House of Representatives initiated the first impeachment proceedings against a sitting president in the history of the United States. The basis for this historic move stemmed from Tyler’s unprecedented use of the veto power, which clashed sharply with the Whig-controlled Congress’s legislative agenda.

Congressman John Botts, a vocal opponent of Tyler, introduced a resolution for impeachment on July 10, 1842. The resolution outlined nine formal articles of impeachment alleging “high crimes and misdemeanors” against Tyler. Six of these charges focused on accusations of political overreach, while the remaining three cited misconduct in office.

Despite Botts’s aggressive stance, Henry Clay, a prominent Whig leader, advocated for a more measured approach to Tyler’s “inevitable” impeachment. Botts’s resolution was initially tabled and later rejected in January 1843 by a vote of 127 to 83.

Following these developments, a House select committee led by John Quincy Adams, known for his opposition to slaveholders like Tyler, condemned Tyler’s use of the veto and criticized his character. Although the committee’s report did not formally recommend impeachment, it highlighted the possibility. In August 1842, the House endorsed the committee’s findings.

John Quincy Adams further proposed a constitutional amendment to reduce the veto override threshold from two-thirds to a simple majority in both houses of Congress, but this proposal did not gain traction.

The Whigs’ efforts to impeach Tyler faltered in the subsequent 28th Congress following the 1842 elections, where they retained control of the Senate but lost the majority in the House. Tyler’s term concluded on March 3, 1845, marked by Congress’s override of his veto on a minor revenue-related bill—a symbolic act as the first override of a presidential veto in U.S. history.

Throughout these turbulent times, Tyler found support among some members of Congress, notably Virginia Congressman Henry Wise and his loyal followers dubbed the “Corporal’s Guard”. In recognition of their support, Tyler appointed Wise as the U.S. Minister to Brazil in 1844.

Foreign Affairs Achievements

John Tyler’s presidency, marked by domestic political turmoil, also saw significant accomplishments in foreign policy, reflecting his advocacy of expansionism and free trade.

Expansionism and Pacific Trade:

Tyler was a staunch advocate of expanding American influence towards the Pacific and promoting free trade. His views echoed those of Andrew Jackson’s efforts to bolster American commerce across the Pacific. Eager to compete with Great Britain in international markets, Tyler dispatched lawyer Caleb Cushing to China. Cushing successfully negotiated the Treaty of Wanghia in 1844, establishing favorable trade terms between the United States and China.

European Trade Relations:

In the same year, Tyler appointed Henry Wheaton as minister to Berlin, where he negotiated a trade agreement with the Zollverein—a coalition of German states managing tariffs. Despite Tyler’s efforts to enhance international trade, this treaty faced rejection from the Whigs, reflecting their opposition to Tyler’s administration.

Military Strengthening:

Tyler also advocated for an increase in military strength, a stance that earned praise from naval leaders. During his presidency, there was a notable expansion in the number of warships, underscoring his commitment to bolstering U.S. military capabilities.

The “Tyler Doctrine” and Hawaii:

In 1842, Tyler applied the Monroe Doctrine to Hawaii in what became known as the “Tyler Doctrine”. This policy asserted American influence in the Pacific and warned Britain against interfering in Hawaiian affairs. Tyler’s actions paved the way for the eventual annexation of Hawaii by the United States in the late 19th century.

John Tyler’s foreign policy initiatives underscored his vision of expanding American influence and promoting trade abroad, despite the challenges and controversies he faced domestically.

Webster-Ashburton Treaty and Western Expansion

Webster-Ashburton Treaty:

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty, negotiated in 1842, resolved several longstanding disputes between the United States and Great Britain. Under the leadership of Secretary of State Daniel Webster and British emissary Lord Ashburton (Alexander Baring), the treaty primarily addressed the following key issues:

- Maine-Canada Border: The treaty established the precise boundary between Maine and Canada, ending decades of tension and occasional conflict over the disputed territory.

- Slave Trade: To address the sensitive issue of the Creole incident, where a ship carrying slaves mutinied and was taken to the Bahamas, the treaty granted both the United States and Britain the right to search each other’s ships suspected of carrying slaves. This joint effort aimed to curb illegal slave trafficking.

- Oregon Territory: Although the treaty attempted to address the Oregon border, negotiations on this matter were inconclusive. The United States and Britain continued joint occupation under the Convention of 1818, with unresolved boundaries in the Oregon Territory.

Western Expansion and Exploration:

- Oregon Territory: President Tyler and his administration were keenly interested in expanding American influence in the Oregon Territory, which stretched from the northern boundary of California to the southern boundary of Alaska. Tyler advocated for the establishment of American forts along a trail to Oregon, aiming to protect settlers and assert U.S. presence in the region.

- John C. Frémont’s Expeditions: Captain John C. Frémont led two significant scientific expeditions into the western territories during Tyler’s presidency. In 1842, Frémont climbed and named Frémont’s Peak (now known as Wyoming’s highest peak), symbolically claiming the Rocky Mountains and western lands for the United States. His 1843-1844 expedition mapped crucial landmarks in Oregon and California, including the Cascade Range and Mount St. Helens, contributing to American knowledge and exploration of the West.

- Florida Statehood: On March 3, 1845, during Tyler’s final day in office, Florida was admitted as the 27th state of the Union, marking a significant event in Tyler’s presidency and American territorial expansion.

John Tyler’s presidency, while turbulent domestically, saw notable achievements in foreign diplomacy with the Webster-Ashburton Treaty and advancements in American exploration and territorial expansion in the West.

Dorr Rebellion and Indian Affairs

Dorr Rebellion:

The Dorr Rebellion, which reached its climax in May 1842, was a significant event in Rhode Island’s history during President Tyler’s administration. Led by Thomas Dorr, the rebels sought to reform Rhode Island’s outdated state constitution, which limited suffrage to landowners. Facing armed opposition from the state’s authorities, Dorr and his supporters attempted to establish a new constitution that would expand voting rights. President Tyler was approached by Rhode Island’s governor and legislature, who requested federal troops to suppress the rebellion. Tyler urged for calm and encouraged the governor to consider expanding the franchise to defuse tensions. Ultimately, the rebellion was quelled by state militia without federal intervention, leading to broader suffrage reforms in Rhode Island.

Indian Affairs:

During Tyler’s presidency, Native American relations were marked by significant conflicts and policies aimed at assimilation:

The Seminole tribe were the last remaining Native American group in the South who had been tricked into signing a fraudulent treaty in 1833, relinquishing their lands. Under the leadership of Chief Osceola, the Seminoles resisted removal by U.S. troops for a decade. Tyler finally brought an end to the long, bloody, and inhumane Seminole War in May 1842, expressing his position in a message to Congress.

Tyler also demonstrated his interest in forcing the cultural assimilation of Native Americans into American society, despite their ongoing struggles.

- Seminole War: The Seminole War, which had been ongoing for nearly a decade, came to an end in May 1842. Under the leadership of Chief Osceola, the Seminoles fiercely resisted forced removal from their lands in the South, culminating in a protracted and often brutal conflict with U.S. troops. Tyler’s administration finally brought an end to the war, though the policies of forced removal and assimilation continued to shape federal Indian policy.

- Cherokee Frauds Investigation: In May 1842, a congressional investigation into alleged Cherokee frauds prompted a clash between President Tyler and the House of Representatives. Tyler asserted executive privilege and refused to comply with the House’s demands to release information related to the investigation. This standoff underscored ongoing tensions between the executive and legislative branches over the extent of presidential powers and congressional oversight.

President Tyler’s tenure was marked by both domestic challenges, such as the Dorr Rebellion and contentious Indian affairs, and significant diplomatic achievements in foreign policy, exemplified by the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. His administration navigated turbulent times with mixed success, leaving a complex legacy in American history.

Annexation of Texas

John Tyler’s pursuit of the annexation of Texas during his presidency was a defining and controversial aspect of his administration. Here are the key events and aspects related to Texas annexation under Tyler:

Background and Early Attempts

- Texas Independence: Texas had declared independence from Mexico in 1836 but struggled to gain recognition from other nations, including the United States. The issue of annexing Texas into the Union became politically charged due to its implications for slavery and sectional tensions.

- Tyler’s Initiative: From early in his presidency, Tyler saw annexation as a critical goal. Despite opposition from Secretary of State Daniel Webster, who advocated focusing on Pacific initiatives, Tyler persisted in his efforts to annex Texas.

- Political Maneuvering: In 1843, Tyler intensified his efforts, recognizing that annexation could bolster his political standing amidst a lack of support from Whigs and Democrats. He strategically replaced cabinet members and appointed pro-annexation figures to key positions.

USS Princeton Disaster

- Tragic Event: On February 28, 1844, aboard the USS Princeton, a ceremonial cruise turned tragic when the ship’s cannon, the “Peacemaker,” exploded. The explosion killed several prominent figures, including Tyler’s Secretary of State Abel Upshur and Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer.

- Impact: The disaster not only caused personal grief for Tyler but also derailed his political momentum and strategic plans for Texas annexation.

Annexation Efforts and Challenges

- Calhoun’s Role: Following the Princeton disaster, Tyler appointed John C. Calhoun as his new Secretary of State. Calhoun, a staunch advocate of slavery, played a pivotal role in advancing the annexation agenda.

- Opposition and Controversy: The annexation treaty faced significant opposition, particularly from abolitionists and those concerned about escalating tensions with Mexico. Both Henry Clay and Martin Van Buren, leading presidential contenders, opposed annexation.

- Calhoun’s Letter: Secretary Calhoun’s controversial letter to the British minister emphasized that annexation was driven by the need to protect American slavery from British interference. This letter underscored the divisive nature of the annexation debate.

Senate Ratification and Legacy

- Senate Debate: Despite Tyler’s efforts, the Senate debated the annexation treaty in April 1844 but did not ratify it before Tyler’s term ended.

- Legacy: Tyler’s pursuit of Texas annexation set the stage for subsequent U.S. actions and tensions leading up to the Mexican-American War. It also highlighted the deep divisions over slavery and expansionism that would ultimately culminate in the Civil War.

John Tyler’s presidency, marked by his steadfast pursuit of Texas annexation amid political and personal challenges, remains a pivotal chapter in American history, reflecting the complexities of 19th-century American expansionism and slavery politics.

Election of 1844

The election of 1844 was a pivotal moment in John Tyler’s presidency, largely centered around the issue of Texas annexation. Here’s an overview of the key events leading up to and following the election:

Tyler’s Political Situation

- Whig and Democratic Divides: After his break with the Whig Party in 1841, Tyler attempted to rejoin the Democratic Party, but faced resistance, particularly from the followers of Martin Van Buren.

- Formation of the Tyler Party: As the election of 1844 approached, Tyler realized his chances of securing a major party nomination were slim. Instead, he used his presidential patronage powers to form a third party, known as the National Democratic Party, composed of his supporters and political networks.

- Tyler’s Nomination: Tyler’s supporters nominated him for the presidency under the Democratic-Republican banner on May 27, 1844, in Baltimore, Maryland. However, his party was loosely organized, lacked a vice presidential nominee, and had no formal platform.

Annexation Strategy

- Negotiations with Texas: In early 1844, Tyler instructed Secretary of State John C. Calhoun to negotiate with Texas President Sam Houston for annexation. Tyler believed annexation was crucial for national expansion and to counter potential British influence in Texas.

- Military Deployment: To bolster annexation efforts and deter Mexican intervention, Tyler ordered U.S. troops to the Texas border in western Louisiana.

Achieving Annexation

- Senate Rejection: In June 1844, the Whig-controlled Senate rejected Tyler’s annexation treaty by a significant margin, prompting Tyler to pursue annexation through a joint resolution of Congress.

- Political Support: Former President Andrew Jackson’s influence and Tyler’s strategic maneuvers helped rally support for annexation among Democrats. Tyler dropped out of the presidential race in August 1844 and endorsed James K. Polk, a pro-annexation candidate.

- Congressional Approval: On February 26, 1845, Tyler’s efforts paid off when Congress passed a joint resolution offering annexation to Texas. Despite narrow margins in the Senate, the resolution was approved, and Tyler signed it into law on March 3, 1845, his last full day in office.

- Texas Statehood: Texas accepted the terms of annexation and officially joined the Union as the 28th state on December 29, 1845, marking the successful culmination of Tyler’s annexation strategy.

John Tyler’s persistence and strategic maneuvers in pursuing Texas annexation, despite initial setbacks and political opposition, left a significant impact on American expansionism and the evolving debate over slavery in the United States during the mid-19th century.

Post-presidency (1845–1862)

After leaving office in 1845, John Tyler settled into private life with a mix of agricultural pursuits, political engagement, and social activities. Here’s an overview of his post-presidential years:

Retirement to Sherwood Forest

- Sherwood Forest: Tyler retired to Sherwood Forest, his plantation on the James River in Charles City County, Virginia. He renamed it in reference to Robin Hood, symbolizing his feeling of being “outlawed” by the Whig Party.

- Agricultural Pursuits: Despite his political career, Tyler took farming seriously and worked diligently to maintain high yields on his plantation.

- Local Office: In 1847, Tyler was appointed overseer of roads by his largely Whig neighbors as a mocking gesture. However, Tyler took the responsibility seriously, frequently calling upon his neighbors to contribute their slaves for road work, much to their displeasure.

Social and Political Engagement

- Social Life: Tyler engaged in the typical activities of Virginia’s elite, hosting parties and socializing with other aristocrats. He also spent summers at “Villa Margaret,” the family’s seaside home.

- Political Return: In 1852, Tyler rejoined the Virginia Democratic Party and remained interested in political affairs, despite his diminished role and influence compared to his presidency.

- Public Speaking: Occasionally called upon to deliver speeches, Tyler spoke at events such as the unveiling of a monument to Henry Clay. He acknowledged their past political conflicts but praised Clay’s efforts, particularly his role in the Compromise Tariff of 1833.

John Tyler’s post-presidential years were characterized by his retreat to private life, continued engagement in agriculture, and occasional involvement in political and social activities within Virginia. His legacy as the 10th President of the United States was marked by his efforts in expanding the nation’s territory and navigating the complex political issues of his time.

Prelude to the American Civil War

John Tyler’s later years were marked by significant involvement in the lead-up to the American Civil War and his eventual alignment with the Confederate cause. Here’s a summary of his activities during this period:

Involvement Before and During the Civil War

- Military Involvement: After John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, Tyler became active in local Virginia militia efforts. He commanded a home guard unit and a cavalry troop, reflecting the heightened tensions and fears of slave rebellion or abolitionist interference.

- Washington Peace Conference: In February 1861, Tyler played a key role as the presiding officer of the Washington Peace Conference in Washington, D.C. The conference aimed to find compromises to prevent the outbreak of Civil War, but Tyler eventually opposed its resolutions, feeling they did not adequately protect Southern interests.

- Secession Convention: Concurrently with his role in the Peace Conference, Tyler was elected to the Virginia Secession Convention. Initially hopeful for compromise, Tyler eventually voted in favor of secession on April 17, 1861, following the attack on Fort Sumter and Abraham Lincoln’s call for troops.

- Confederate Service: After Virginia seceded, Tyler was elected to the Provisional Confederate Congress in June 1861. He served in the Confederate Congress until shortly before his death in early 1862.

Death and Legacy

- Death: John Tyler died on January 18, 1862, in Richmond, Virginia, at the age of 71. He suffered from poor health throughout his life and likely died of a stroke. His death marked the end of a tumultuous political career that spanned the early years of the United States’ history.

- Burial: Tyler was buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, under a Confederate flag, a reflection of his allegiance to Virginia and the Confederate cause during the Civil War. He remains the only U.S. president buried under a flag other than that of the United States.

- Legacy: Despite his controversial political decisions later in life, including his support for secession, John Tyler left a lasting impact on American history. He is remembered particularly for his role in the annexation of Texas, which expanded the territory of the United States significantly.

John Tyler’s legacy is complex, reflecting the turbulent political climate and divisions leading up to the Civil War. His actions during this period cemented his place in history as a pivotal figure in the transition from the antebellum era to the Civil War era in the United States.

Historical reputation and legacy

John Tyler’s historical reputation is a subject of considerable debate among historians and scholars. Here’s a summary of how his presidency and legacy have been viewed over time:

Historical Assessment of Presidency

- Low Esteem: Generally, historians have not held Tyler’s presidency in high regard. He is often criticized for being ineffective and facing significant opposition, especially from Congress. His presidency is frequently ranked as one of the least successful in U.S. history due to his struggles with Congress and the lack of major legislative accomplishments.

- Significant Precedents: Despite criticisms of his administration, Tyler is credited with establishing important precedents. Most notably, he asserted his full presidential powers upon assuming office after William Henry Harrison’s death, setting a precedent followed by subsequent vice presidents who ascended to the presidency. This was later affirmed in the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

- Foreign Policy and Achievements: Some scholars highlight Tyler’s achievements in foreign policy, such as the Webster–Ashburton Treaty with Great Britain and the annexation of Texas. These actions expanded the nation’s territory and improved diplomatic relations, though they also fueled tensions over slavery.

- Mixed Views: There are contrasting opinions among historians regarding Tyler’s presidency. While some, like Richard P. McCormick, argue that Tyler was a strong president who conducted himself with dignity and effectiveness, others maintain that his presidency was overshadowed by his later allegiance to the Confederacy, which tarnished his legacy.

Legacy and Public Perception

- Obscurity: Despite his historical significance, John Tyler remains relatively obscure among the general public. He is often remembered, if at all, for being the subject of a catchy campaign slogan (“Tippecanoe and Tyler too”) rather than for his presidential accomplishments.

- Criticism and Praise: Tyler’s decision to align with the Confederacy during the Civil War significantly impacted his posthumous reputation. While some praise his integrity and principles, others argue that his support for secession overshadowed any positive contributions he made earlier in his career.

- Historical Context: Some scholars argue that Tyler’s presidency was greatly influenced by external factors, such as the dominance of Henry Clay in Congress and the broader political climate of the time. These factors contributed to the challenges Tyler faced during his presidency.

In summary, John Tyler‘s presidency is characterized by a mix of achievements in foreign policy and the establishment of precedents, along with criticism for his struggles with Congress and his controversial later actions. His legacy remains complex and subject to ongoing historical reinterpretation.

Family, personal life, slavery

Family Life

- Marriages and Children:

- First Wife, Letitia Christian: Tyler had eight children with Letitia, who tragically died of a stroke while he was president in 1842.

- Second Wife, Julia Gardiner: After Letitia’s death, Tyler married Julia Gardiner in 1844. They had seven children together.

- Parenting Challenges: Tyler’s political career often kept him away from home for extended periods. Despite this, he maintained a close relationship with his children through letters, emphasizing the importance of education and family ties.

- Longevity of Family Connections: Remarkably, Tyler’s grandson, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, born in 1928, continues to maintain the family home, Sherwood Forest Plantation. This makes Harrison Tyler the earliest former president with a living grandchild, underscoring the longevity of Tyler’s familial legacy.

Views on Slavery

- Slavery and Ownership:

- Tyler owned a substantial number of slaves, with records indicating he held around 40 slaves at Greenway.

- While Tyler privately acknowledged slavery as morally wrong, he believed it was a matter of states’ rights and opposed federal intervention to abolish it.

- He did not free any of his own slaves during his lifetime, aligning with his political beliefs on states’ rights and the limits of federal authority.

- Controversies and Allegations:

- Tyler faced allegations, particularly from abolitionists like Joshua Leavitt, regarding his treatment of slaves and allegations of fathering children with them. These claims were unsubstantiated, but Tyler’s stance on slavery and his actions as a slaveholder remain controversial.

- Economic Impact:

- Despite significant wealth, estimated at over $50 million in today’s value at its peak, Tyler faced financial difficulties during the Civil War and died in poorer circumstances.

John Tyler’s personal life, family dynamics, and views on slavery are integral parts of his historical legacy, reflecting the complexities of his era and the challenges he faced as both a leader and a private individual.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Tyler