James Monroe 5th President, born on April 28, 1758, and passing away on July 4, 1831, was a key figure in early American history, renowned as a statesman, lawyer, and diplomat. He served as the fifth President of the United States from 1817 to 1825, representing the Democratic-Republican Party and marking the end of the Virginia dynasty among the Founding Fathers.

Monroe’s presidency coincided with the Era of Good Feelings, a period characterized by national unity following the War of 1812 and the fading of the First Party System in American politics. One of his most significant contributions was the Monroe Doctrine, a policy aimed at limiting European colonial ambitions in the Americas, which became a cornerstone of American foreign policy.

Before becoming president, Monroe had a distinguished career. He served as governor of Virginia, a United States Senator, and held several diplomatic roles including ambassador to France and Britain. Monroe also played a crucial role in negotiating the Louisiana Purchase while serving as President Thomas Jefferson’s special envoy.

Despite his initial opposition to the United States Constitution, Monroe went on to become a prominent leader of the Democratic-Republican Party, supporting fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson’s presidency and later serving in James Madison’s administration as Secretary of State and Secretary of War during the War of 1812.

Monroe’s presidency saw the collapse of the Federalist Party as a national force, and he was re-elected in 1820 virtually unopposed. His administration was marked by the signing of the Missouri Compromise, which addressed the issue of slavery expansion, and the acquisition of Florida through the Adams–Onís Treaty with Spain.

In foreign affairs, Monroe and his Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, pursued a policy of conciliation with Britain and sought to expand American influence against the Spanish Empire. The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 solidified the United States’ stance against European intervention in the newly independent countries of Latin America.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Monroe/Later-years-and-assessment

Outside of politics, Monroe was a supporter of the American Colonization Society, which advocated for the resettlement of freed slaves in Africa, and the capital of Liberia, Monrovia, is named in his honor.

James Monroe’s legacy as a president, diplomat, and patriot endures as a pivotal figure in shaping American foreign policy and consolidating the nation’s territorial expansion and internal unity during its formative years.

James Monroe was the fifth President of the United States, serving from 1817 to 1825. He was a prominent figure in early American politics and played a significant role in shaping the nation’s foreign policy, particularly with the Monroe Doctrine, which warned European powers against further colonization or intervention in the Americas.

Monroe was also known for overseeing a period of national unity and economic growth, often referred to as the Era of Good Feelings. His presidency was marked by territorial expansion, including the acquisition of Florida, and efforts to stabilize the young nation after the War of 1812. Monroe’s tenure is also associated with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which sought to maintain the balance between free and slave states in the Union.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

Early life and education Of

James Monroe 5th President

Monroe’s early education began at the local schools in Virginia, where he showed promise and a keen interest in learning. He later attended Campbelltown Academy and then studied under Reverend Archibald Campbell, a Scottish Presbyterian minister, who mentored him in classical languages and other subjects.

In 1774, at the age of 16, Monroe entered the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, where he continued his education. However, his studies were interrupted by the American Revolutionary War, which began in 1775. Like many of his peers, Monroe left college to join the fight for American independence.

During the war, Monroe enlisted in the Continental Army in 1776 and served under General George Washington. He demonstrated courage and dedication, participating in several key battles, including the Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Monmouth. Monroe’s military service played a formative role in shaping his patriotism and commitment to the ideals of the American Revolution.

After the war ended in 1783, Monroe returned to his studies and completed his legal education under the guidance of Thomas Jefferson, who became a lifelong mentor and friend. Jefferson’s influence profoundly impacted Monroe’s political philosophy and career trajectory.

Monroe’s early experiences in Virginia, his education, and his service in the Revolutionary War laid the foundation for his future roles as a statesman, diplomat, and ultimately, the fifth President of the United States. His journey from a young Virginian during the colonial era to a leader on the national stage reflected the transformative period in American history during which he lived.

Revolutionary War service

James Monroe’s service during the Revolutionary War was notable for its dedication and the valuable experience it provided him as a young patriot. In 1776, at the age of 18, Monroe enlisted in the Continental Army, reflecting his commitment to the American cause for independence. He served under the command of General George Washington, participating in several key battles and campaigns that were pivotal to the war effort.

Monroe’s military career included significant engagements such as the Battle of Trenton in 1776, where Washington’s daring crossing of the Delaware River resulted in a crucial American victory. He also fought at the Battle of Brandywine in 1777 and the Battle of Monmouth in 1778, where he demonstrated bravery and resilience amidst the challenges of wartime conditions.

Throughout his service, Monroe rose to the rank of major, demonstrating leadership and a steadfast dedication to the principles of liberty and self-determination that motivated the American colonies in their struggle against British rule. His experiences in the military instilled in him a deep sense of patriotism and a commitment to public service that would shape his future career in American politics.

Monroe’s wartime service not only contributed to the eventual victory of the American colonies but also provided him with firsthand knowledge of the challenges faced by the young nation. His military background would later bolster his credibility as a statesman and diplomat, as he navigated the complexities of early American foreign policy and governance.

Overall, Monroe’s Revolutionary War service stands as a testament to his courage, leadership, and commitment to the ideals of the American Revolution. It played a crucial role in shaping his character and prepared him for the significant roles he would undertake in shaping the future of the United States.

Early Political Career of James Monroe

James Monroe’s early political career was marked by his active involvement in shaping the young nation’s governance and diplomatic efforts.

- Delegate to the Continental Congress: Monroe’s political journey began in 1783 when he was elected as a delegate to the Continental Congress, representing Virginia. This role allowed him to contribute to the post-Revolutionary War reconstruction efforts and to advocate for the interests of his home state.

- Opposition to the Constitution: Initially skeptical of the proposed U.S. Constitution due to concerns over states’ rights and individual liberties, Monroe aligned with the Anti-Federalists and played a role in shaping early debates surrounding the ratification process.

- Diplomatic Service: Monroe’s diplomatic career began in 1794 when President George Washington appointed him as Minister to France. He played a crucial role in negotiating the release of American prisoners and in attempting to improve relations between France and the United States during a tumultuous period in European history.

- Governor of Virginia: In 1799, Monroe was elected as Governor of Virginia, where he focused on domestic issues and the state’s recovery from the Revolutionary War.

- U.S. Senate: Monroe served two terms in the United States Senate, representing Virginia from 1790 to 1794 and from 1803 to 1807. During his tenure, he became a prominent figure in the Democratic-Republican Party, advocating for agrarian interests and a more limited federal government.

- Early Presidential Candidacy: Monroe ran for President in 1808 but was defeated by James Madison in the Democratic-Republican Party’s nomination process. Despite this setback, Monroe’s continued service in various diplomatic and governmental roles cemented his reputation as a capable and dedicated public servant.

James Monroe’s early political career laid the groundwork for his later achievements as President of the United States and his significant contributions to American foreign policy and domestic affairs. His experiences in diplomacy, governance, and legislative affairs prepared him well for the challenges he would face in higher office.

Marriage and Law Practice of James Monroe

James Monroe’s personal and professional life intersected significantly during his marriage and law practice, shaping his early career and personal development.

On February 16, 1786, James Monroe married Elizabeth Kortright (1768–1830) at Trinity Church in Manhattan, New York City. Elizabeth hailed from New York City’s elite circles. Their union was blessed with three children: Eliza in 1786, James in 1799, and Maria in 1802. Although Monroe was raised Anglican, their children received their education in accordance with Episcopal Church teachings. Following a brief honeymoon on Long Island, the Monroes resided in New York City with Elizabeth’s father until Congress adjourned.

- Marriage to Elizabeth Kortright: In 1786, Monroe married Elizabeth Kortright, a New York native known for her grace and intelligence. Their marriage provided Monroe with a supportive partner who shared his commitment to public service and the challenges of political life.

- Law Practice in Virginia: Following his marriage, Monroe established a successful law practice in Fredericksburg, Virginia. His legal career flourished as he represented clients in various civil and criminal cases, earning a reputation for his integrity and dedication to justice.

- Public Service During Marriage: Despite his focus on law, Monroe continued his public service, serving as a delegate to the Virginia Convention that ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1788. His involvement in constitutional debates reflected his ongoing commitment to shaping the future of the young nation.

- Diplomatic Responsibilities: Throughout his law practice, Monroe’s diplomatic responsibilities occasionally took precedence. He served as Minister to France from 1794 to 1796, negotiating treaties and advocating for American interests abroad during a turbulent period in European history.

- Family Life: Monroe and Elizabeth raised two daughters, Eliza and Maria, amid the demands of his career in law and diplomacy. Their partnership provided stability and support as Monroe navigated the challenges of public office and political life.

- Impact on Career: Monroe’s marriage and law practice not only provided personal fulfillment but also enhanced his political stature and capabilities. His legal expertise complemented his diplomatic skills, laying the groundwork for his future roles as Governor of Virginia, U.S. Senator, and ultimately, President of the United States.

James Monroe’s marriage to Elizabeth Kortright and his law practice in Virginia were integral to his personal happiness and professional success. These experiences enriched his understanding of law, governance, and diplomacy, preparing him for the leadership roles he would undertake in service to his country.

Senator

In the 1789 election for the 1st United States Congress, anti-Federalist Henry Monroe convinced James Monroe to challenge James Madison. Henry Monroe orchestrated the redrawing of a congressional district in Virginia aimed at favoring James Monroe’s candidacy. Despite running against each other, James Madison and James Monroe maintained a strong friendship during the campaign, often traveling together.

Ultimately, Madison prevailed in the election for Virginia’s Fifth District with 1,308 votes compared to Monroe’s 972 votes. Following this defeat, Monroe relocated his family from Fredericksburg to Albemarle County. They first settled in Charlottesville and later moved to a nearby area close to Monticello, where Monroe purchased an estate he named Highland.

After Senator William Grayson’s death in 1790, Virginia legislators appointed Monroe to complete Grayson’s Senate term. Unlike the more public House of Representatives, Senate proceedings were conducted behind closed doors, drawing less public attention. Monroe advocated for open Senate sessions starting in February 1791, although this proposal was initially rejected and only implemented in February 1794.

During George Washington’s presidency, American politics grew increasingly divided between the Anti-Administration Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, and the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton. Monroe aligned himself closely with Jefferson in opposing Hamilton’s vision of a strong central government and executive power. As the Democratic-Republican Party formed around Jefferson and Madison, Monroe emerged as a key leader in the Senate. He also played a role in organizing opposition to John Adams in the 1792 election, although Adams ultimately won re-election as vice president.

Monroe’s involvement in congressional inquiries into Alexander Hamilton’s financial dealings in 1792 uncovered what became the first political sex scandal in the United States. These investigations revealed payments made to keep Hamilton’s affair with James Reynolds’ wife secret. Hamilton never forgave Monroe for his role in exposing this scandal, and tensions between the two nearly led to a duel.

In response to Alexander Hamilton’s pamphlets accusing Jefferson of undermining Washington’s authority, Monroe and Madison authored a series of six essays in 1792 and 1793. These essays, largely written by Monroe, sharply rebutted Hamilton’s accusations. As leader of the Republicans in the Senate, Monroe also became increasingly involved in matters of foreign relations. In 1794, he opposed Hamilton’s nomination as ambassador to the United Kingdom and supported the First French Republic. Since 1791, Monroe had publicly aligned himself with the ideals of the French Revolution, often expressing his views under the pseudonym Aratus.

Minister to France

As the 1790s progressed, the French Revolutionary Wars increasingly shaped U.S. foreign policy, with both British and French actions threatening American trade with Europe. James Monroe, aligned with the Jeffersonian faction, supported the ideals of the French Revolution, while Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist supporters leaned towards Britain. In 1794, seeking to navigate a path of neutrality amid escalating tensions, President Washington appointed Monroe as the U.S. minister (ambassador) to France, after both James Madison and Robert R. Livingston declined the role.

Monroe’s appointment came at a challenging time. The United States, lacking military strength, faced difficulty asserting its interests amid the conflict between France and Britain, which further exacerbated divisions between the Anglophile Federalists and Francophile Republicans. While Federalists aimed primarily for independence from Great Britain, Republicans advocated for revolutionary government ideals and strongly sympathized with the First French Republic.

Upon arriving in France, Monroe delivered a passionate address to the National Convention, receiving acclaim for his celebration of republicanism. However, his enthusiastic speech was criticized by John Jay for its sentimentality, and President Washington viewed it as poorly timed and not well-suited given America’s neutrality in the ongoing conflict.

Despite these initial challenges, Monroe achieved early diplomatic successes. He secured protection for U.S. trade against French attacks and used his influence to negotiate the release of American citizens and notable figures like Adrienne de La Fayette and Thomas Paine, although his relationship with Paine soured when the latter criticized Washington despite Monroe’s objections.

Monroe’s tenure coincided with the signing of the Jay Treaty between the U.S. and Britain, which he viewed unfavorably, and which strained Franco-American relations. Nonetheless, Monroe succeeded in gaining French support for U.S. navigational rights on the Mississippi River, crucial for American commerce controlled by Spain at its mouth. Additionally, in 1795, the U.S. and Spain signed Pinckney’s Treaty, granting limited American access to the port of New Orleans.

Upon the appointment of Timothy Pickering as Secretary of State in 1795, Monroe faced increasing opposition. He was criticized for his incomplete handling of French complaints regarding the Jay Treaty and accused of failing to protect American interests effectively. Influenced by Alexander Hamilton, Pickering persuaded President Washington to recall Monroe in November 1796, citing inefficiency and disruption of national interests.

Returning to Charlottesville, Monroe resumed his roles as a farmer and lawyer, declining suggestions from Jefferson and Madison to run for Congress and instead focusing on state politics. In 1797, Monroe published “A View of the Conduct of the Executive” which sharply criticized Washington’s administration, accusing it of favoring British interests over American rights, despite cautionary advice from his friend Robert Livingston to moderate his criticisms.

Washington, in response, noted Monroe’s susceptibility to foreign influence and his reluctance to advocate firmly for American interests. This marked the end of Monroe’s first diplomatic tenure but foreshadowed his enduring commitment to defending what he perceived as the true interests of the United States.

Governor of Virginia and diplomat (1799–1802, 1811)

Governor of Virginia and Diplomat (1799–1802, 1811)

James Monroe’s tenure as Governor of Virginia and subsequent diplomatic roles underscored his leadership and diplomatic skills during pivotal moments in American history.

- Governor of Virginia (1799–1802):

After his recall from France in 1796, James Monroe returned to Virginia and assumed the role of Governor from 1799 to 1802. During his governorship, Monroe focused on rebuilding Virginia’s economy and infrastructure following the Revolutionary War. He advocated for internal improvements such as road and canal construction to stimulate economic growth and enhance transportation networks. - Diplomatic Mission to France (1803):

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson appointed Monroe as special envoy to France to negotiate the Louisiana Purchase. Alongside Robert R. Livingston, Monroe successfully secured the acquisition of the vast territory from France, doubling the size of the United States and securing its western expansion. - Minister to the United Kingdom (1803–1807):

Following his role in the Louisiana Purchase, Monroe served as Minister (Ambassador) to the United Kingdom from 1803 to 1807. He worked to improve Anglo-American relations strained by maritime disputes and British impressment of American sailors. Monroe’s diplomatic efforts aimed to prevent conflict and protect American interests amid European hostilities. - Secretary of State (1811):

Appointed by President James Madison in 1811, Monroe served briefly as Secretary of State. He played a critical role in managing U.S. foreign relations, particularly during the early stages of the War of 1812 against Britain. Monroe’s diplomatic experience and leadership were instrumental in navigating the challenges of wartime diplomacy and asserting American sovereignty.

James Monroe’s dual roles as Governor of Virginia and diplomat highlight his versatility and dedication to public service. His diplomatic achievements, including the Louisiana Purchase and efforts to safeguard American interests abroad, solidified his legacy as a key figure in shaping early American expansion and foreign policy.

Governor of Virginia

On a partisan vote, James Monroe was elected Governor of Virginia by the state legislature in 1799, a position he held until 1802. Despite the limited powers granted to the governor by Virginia’s constitution, Monroe leveraged his influence to advocate for expanded state involvement in transportation, education, and militia training. He introduced State of the Commonwealth addresses to the legislature, urging action on key legislative priorities.

During his governorship, Monroe led initiatives to establish Virginia’s first penitentiary, promoting imprisonment as a more humane alternative to harsh punishments. In 1800, he mobilized the state militia to quell Gabriel’s Rebellion, a significant slave uprising near Richmond. The rebellion’s suppression led to the execution of Gabriel and 27 others, sparking widespread sympathy and prompting Monroe to collaborate with legislators on measures to exile suspected conspirators, both free and enslaved, outside the United States.

Monroe attributed the Quasi War of 1798–1800 to foreign interference and Federalist opposition. He ardently supported Thomas Jefferson’s presidential bid in 1800, using his authority to appoint election officials in Virginia to bolster Jefferson’s electoral support. Monroe even contemplated using the Virginia militia to sway the election in Jefferson’s favor. Jefferson’s victory secured Monroe’s position within the Democratic-Republican Party, positioning him as one of Jefferson’s potential successors alongside James Madison.

Acquisition of Louisiana Territory and Diplomatic Service in Britain

After completing his term as governor, President Jefferson dispatched James Monroe back to France to aid Ambassador Robert Livingston in negotiating the Louisiana Purchase. The Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800 had seen France acquire Louisiana from Spain, and rumors circulated in the U.S. that West Florida was included. Initially seeking only New Orleans and West Florida, crucial for controlling Mississippi River trade, Jefferson authorized Monroe to explore a British alliance if France resisted selling New Orleans, even if it meant war.

In discussions with French Foreign Minister François Barbé-Marbois, Monroe and Livingston negotiated the purchase of the entire Louisiana Territory for $15 million, a move exceeding Monroe’s $9 million instructions intended solely for New Orleans and West Florida. Although France did not concede that West Florida remained Spanish, the U.S. would assert ownership for years. Jefferson strongly supported Monroe’s actions despite constitutional doubts about acquiring foreign land, securing congressional approval and doubling U.S. territory.

In 1805, Monroe ventured to Spain to negotiate the acquisition of West Florida, but faced diplomatic setbacks exacerbated by the blunt tactics of American Ambassador Charles Pinckney. Spain, supported by France, rebuffed Monroe’s attempts to resolve territorial disputes concerning New Orleans, West Florida, and the Rio Grande.

Following Rufus King’s resignation, Monroe assumed the role of U.S. ambassador to Great Britain in 1803. The primary issue between the nations was British impressment of American sailors. Despite efforts to halt this practice, strained relations persisted, exacerbated by Jefferson’s clashes with British Minister Anthony Merry. Monroe declined Jefferson’s offer to govern the Louisiana Territory, serving as ambassador until 1807.

In 1806, Monroe negotiated the Monroe–Pinkney Treaty with Britain, aiming to extend the expired Jay Treaty of 1794. Although the treaty promised a decade of trade and protections for American merchants, Jefferson, displeased that it did not address impressment, refused to submit it for Senate ratification. This decision contributed to escalating tensions, ultimately leading to the War of 1812. Monroe’s disappointment over the treaty’s rejection strained his relationship with Secretary of State James Madison.

1808 election and the Quids

Upon returning to Virginia in 1807, James Monroe was warmly welcomed, with many urging him to run in the upcoming 1808 presidential election. Monroe, disappointed by Jefferson’s refusal to submit the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty, believed Jefferson’s decision was aimed at preventing Monroe from overshadowing Madison in the 1808 race. Out of respect for Jefferson, Monroe agreed not to actively campaign for the presidency but remained open to a draft effort.

The Democratic-Republican Party was increasingly divided, with factions like the “Old Republicans” or “Quids” criticizing Jefferson’s administration for abandoning what they saw as true republican principles. Led by John Randolph of Roanoke, the Quids sought to enlist Monroe to run for president in 1808, potentially in alliance with the Federalist Party, which had strong support in New England. Monroe’s decision to challenge Madison in the election aimed to assert his political strength in Virginia.

Despite efforts by the Quids, regular Democratic-Republicans maintained control during the nominating caucus, ensuring Madison’s nomination and support base. Monroe refrained from publicly criticizing Jefferson or Madison during Madison’s successful campaign against Federalist Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Although Monroe garnered 3,400 votes in Virginia, his candidacy received little backing elsewhere, and Madison won decisively, carrying all but one state outside New England.

Monroe’s presidential bid strained his relationships within the Republican Party, leading him to withdraw from active political life for the next few years. His attempt to sell his Loudon County estate, Oak Hill, to fund renovations at Highland, his estate near Charlottesville, faced challenges due to low real estate prices. Despite initial strains with Jefferson over political differences, Monroe eventually reconciled with him, though their friendship faced further tests when Jefferson did not support Monroe’s congressional candidacy in 1809. Monroe focused on agricultural pursuits at Highland, experimenting with new farming methods to transition from declining tobacco cultivation to wheat production.

Dual Cabinet Roles: Secretary of State and Secretary of War (1811–1817)

Service as Secretary of State and Secretary of War (1811–1817)

James Monroe assumed the dual roles of Secretary of State and Secretary of War during a pivotal period in American history, marked by the War of 1812 and subsequent diplomatic efforts.

- Appointment and Responsibilities:

- Monroe was appointed by President James Madison to serve as both Secretary of State and Secretary of War concurrently in 1811.

- As Secretary of State, Monroe played a crucial role in managing foreign relations, diplomatic negotiations, and international treaties.

- As Secretary of War, he oversaw military affairs, including troop deployments, defense strategy, and logistical support during the War of 1812.

- War of 1812:

- Monroe’s tenure coincided with the outbreak of the War of 1812 against Britain, sparked by maritime disputes, British impressment of American sailors, and support for Native American tribes resisting American expansion.

- He worked closely with President Madison to mobilize the military, coordinate naval operations, and defend American territory from British incursions.

- Diplomatic Efforts:

- Despite the challenges of war, Monroe continued to engage in diplomatic efforts to negotiate peace with Britain.

- He collaborated with diplomats such as John Quincy Adams and Albert Gallatin to explore diplomatic solutions and peace treaties to end the conflict.

- Post-War Treaty Negotiations:

- Monroe played a key role in negotiating the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, which ended the War of 1812 and restored peaceful relations between the United States and Britain.

- He also worked on diplomatic initiatives to resolve border disputes and secure U.S. interests in North America, contributing to the stabilization of post-war relations.

- Domestic Policy and Administration:

- In addition to his diplomatic and military duties, Monroe supported domestic policies aimed at strengthening national defense, infrastructure development, and economic growth.

- He advocated for internal improvements and military preparedness to safeguard American sovereignty and promote westward expansion.

- Legacy:

- Monroe’s tenure as Secretary of State and Secretary of War highlighted his leadership, diplomatic acumen, and dedication to advancing American interests on both the international and domestic fronts.

- His contributions laid the groundwork for subsequent administrations and reinforced his reputation as a statesman committed to national unity and security.

James Monroe’s service as Secretary of State and Secretary of War underscored his pivotal role in shaping American foreign policy and military strategy during a transformative period in the nation’s history.

Madison administration

Return to Virginia and Dual Cabinet Roles (1811–1817)

In 1810, James Monroe returned to the Virginia House of Delegates and was soon elected governor in 1811. However, his term as governor lasted only four months. Less than two months into his term, President Madison asked Monroe to succeed Robert Smith as Secretary of State. In April 1811, Monroe accepted the role, hoping to bolster support from the more radical Democratic-Republicans. Madison also believed Monroe’s extensive diplomatic experience would improve the administration’s performance. The two men mended their past differences over the Monroe-Pinkney Treaty, and their friendship was restored. The Senate confirmed Monroe unanimously, 30–0.

Upon taking office, Monroe sought to negotiate treaties with Britain and France to end attacks on American merchant ships. While France agreed to ease its attacks and release seized ships, Britain was less cooperative. Initially striving for peace, Monroe eventually sided with the “war hawks,” including House Speaker Henry Clay, who favored war with Britain. With Monroe’s support, Madison asked Congress to declare war on Britain, which they did on June 18, 1812, initiating the War of 1812.

The war quickly turned problematic, prompting the administration to seek peace, which the British rebuffed. Despite this, the U.S. Navy experienced successes after Monroe convinced Madison to deploy the Navy’s ships. Following the resignation of Secretary of War William Eustis, Monroe briefly served as acting Secretary of War until General John Armstrong was confirmed. Monroe and Armstrong disagreed on war policy, and Armstrong blocked Monroe’s ambition to lead an invasion of Canada. Monroe advocated for better defenses for Washington, D.C., and the establishment of a military intelligence service in the Chesapeake Bay, but Armstrong dismissed these measures.

During the British invasion in the summer of 1814, Monroe took proactive measures by scouting the Chesapeake Bay himself and warning President Madison of an impending attack. This allowed Madison and his wife to evacuate in time. On August 24, 1814, the British burned the U.S. Capitol and the White House. Subsequently, Madison removed Armstrong and appointed Monroe as Secretary of War on September 27. Monroe resigned as Secretary of State on October 1 but continued to effectively handle both roles until February 28, 1815.

As Secretary of War, Monroe instructed General Andrew Jackson to defend New Orleans against a likely British attack and called for militias from neighboring states to reinforce Jackson. He urged Congress to draft 100,000 soldiers, increase military pay, and establish the Second Bank of the United States to finance the war. The War of 1812 ended with the Treaty of Ghent, restoring the status quo ante bellum. News of the treaty reached the U.S. shortly after Jackson’s victory in New Orleans, leading to widespread celebration. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 saw the British cease the practice of impressment. After the war, Congress established the Second Bank of the United States.

Monroe resigned as Secretary of War in March 1815, resuming leadership of the State Department. Emerging politically strengthened from the war; Monroe became a promising candidate for the presidency.

Election of 1816

Monroe decided to pursue the presidency in the 1816 election, with his leadership during the war positioning him as Madison’s natural successor. He garnered substantial support within the party, yet faced opposition at the Democratic-Republican congressional nominating caucus. With the Federalist Party in decline, perceived as unpatriotic due to their pro-British stance and opposition to the War of 1812, the Democratic-Republican caucus became crucial for Monroe’s bid.

Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford attracted support from many Southern and Western Congressmen, while Governor Daniel D. Tompkins was backed by several New York Congressmen. Crawford particularly appealed to Democratic-Republicans who were skeptical of Madison and Monroe’s endorsement of the Second Bank of the United States. Despite his significant support, Crawford chose to defer to Monroe, anticipating a future presidential run as Monroe’s successor. Monroe secured the party’s nomination, and Tompkins was chosen as the vice-presidential candidate.

The weakened Federalists nominated Rufus King, but they posed little threat after the conclusion of a popular war they had opposed. Monroe triumphed in the election, securing 183 of the 217 electoral votes, winning every state except Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Delaware. As a former Continental Army officer during the Revolutionary War and a delegate in the Continental Congress, Monroe became the last president who was a Founding Father.

Presidency (1817–1825)

James Monroe’s presidency, spanning from 1817 to 1825, is often referred to as the “Era of Good Feelings” due to the period’s relative political harmony and nationalistic fervor. Upon taking office, Monroe embarked on a goodwill tour across the country, aiming to unify the nation following the divisive War of 1812. His widespread popularity helped to ease partisan tensions and foster a sense of national unity.

Monroe’s administration focused on several key domestic and foreign policies. Domestically, he advocated for infrastructure improvements, known as “internal improvements,” which included the construction of roads, canals, and bridges to facilitate economic growth and regional connectivity. Despite the limited federal support for such projects, Monroe’s vision laid the groundwork for future developments in the American transportation network.

Monroe also dealt with significant issues related to westward expansion. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was a pivotal moment during his presidency. The compromise allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state and Maine as a free state, maintaining the balance of power between free and slave states. It also established the 36°30′ parallel as the line dividing future free and slave territories, temporarily easing sectional tensions over slavery.

In foreign affairs, Monroe’s presidency is best known for the Monroe Doctrine, articulated in 1823. This policy declared that the Western Hemisphere was no longer open to European colonization and that any attempts by European powers to interfere in the affairs of nations in the Americas would be viewed as acts of aggression, necessitating U.S. intervention. The doctrine asserted U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere and laid the foundation for future American foreign policy.

Monroe’s presidency also saw the acquisition of Florida from Spain in 1819 through the Adams-Onís Treaty. This treaty not only ceded Florida to the United States but also defined the boundary between the U.S. and Spanish territories in the West, further facilitating American expansion.

During his tenure, Monroe faced economic challenges, most notably the Panic of 1819. This financial crisis was the first major peacetime economic depression in the United States and was caused by a combination of speculative lending practices, the decline of European demand for American goods, and the contraction of credit. Monroe’s administration worked to stabilize the economy, though recovery was slow and contributed to ongoing debates about banking and monetary policy.

Despite these challenges, Monroe left office in 1825 with his reputation largely intact. His presidency is remembered for its efforts to promote national unity, territorial expansion, and the establishment of key foreign policy principles. Monroe’s leadership helped to shape the early 19th-century United States and set the stage for its emergence as a significant power in the Western Hemisphere.

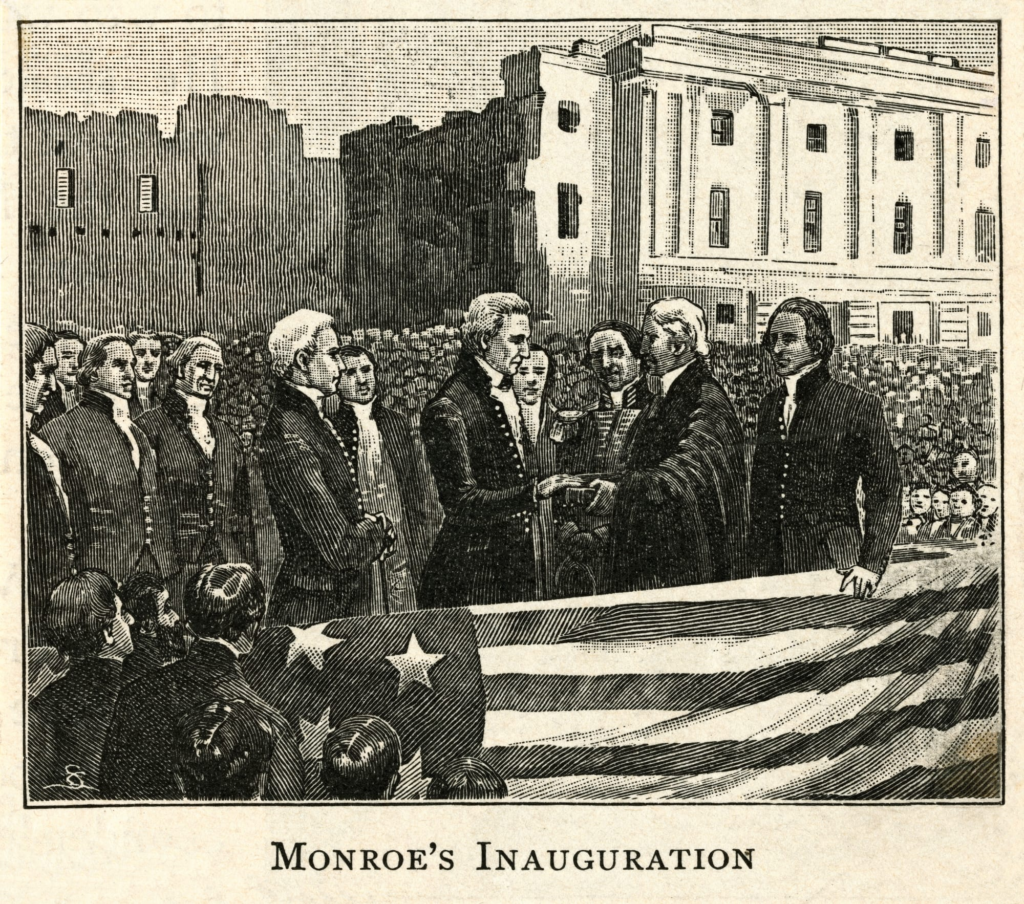

Monroe’s Inauguration and Early Presidency

James Monroe’s inauguration occurred on March 4, 1817, marking the start of a presidency that would come to be known as the “Era of Good Feelings.” This term emerged as Monroe took office during a time of peace and economic stability. The Republican Party, dominant after Madison’s presidency, had integrated several Federalist policies, including the establishment of a central bank and protective tariffs.

Monroe sought to transcend old party divisions when making federal appointments, which helped reduce political tensions and foster a sense of national unity. To further this goal, he embarked on two extensive national tours, participating in welcoming ceremonies and expressing goodwill, which helped build national trust.

He appointed a geographically diverse cabinet, ensuring balanced representation. Monroe retained William H. Crawford as Secretary of the Treasury and kept Benjamin Crowninshield as Secretary of the Navy and Richard Rush as Attorney General. To address Northern concerns about the continuation of the Virginia dynasty, Monroe appointed John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts as Secretary of State. Adams, an experienced diplomat who had left the Federalist Party in 1807 to support Thomas Jefferson’s foreign policy, was seen as a likely successor to Monroe. This appointment was also intended to encourage more Federalists to switch allegiances.

After General Andrew Jackson declined the role of Secretary of War, Monroe appointed South Carolina Congressman John C. Calhoun, thus leaving the Cabinet without a significant Western representative. Later in 1817, Rush became the ambassador to Britain, and William Wirt succeeded him as Attorney General. With the exception of Crowninshield, Monroe’s initial cabinet appointees remained in place throughout his presidency.

Foreign Policy

Monroe’s administration was marked by significant foreign policy achievements, most notably the Monroe Doctrine, which asserted U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere and laid the groundwork for future American foreign policy principles. Additionally, the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, in which Spain ceded Florida to the United States and established a boundary between U.S. and Spanish territories, facilitated American expansion and strengthened Monroe’s reputation as a leader in foreign affairs.

Treaties with Britain and Russia

Upon taking office, Monroe sought to improve relations with Britain following the War of 1812. In 1817, the U.S. and Britain signed the Rush–Bagot Treaty, which regulated naval armaments on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain and demilitarized their border. The Treaty of 1818 fixed the Canada-U.S. border from Minnesota to the Rocky Mountains at the 49th parallel and established a joint U.S.-British occupation of Oregon Country for ten years. These treaties enhanced trade and avoided a costly naval arms race.

In the Pacific Northwest, American claims clashed with Tsarist Russia and Britain. In 1821, Russia extended its territorial claim south to 51° latitude. The Russo-American Treaty of 1824 resolved this by setting the southern limit of Russian territory at 54°40′, the southern tip of the Alaska Panhandle.

Acquisition of Florida

In October 1817, the U.S. cabinet held extensive meetings to address South American independence declarations and rising piracy from Amelia Island. Piracy, driven by smugglers, slave traders, and privateers from Spanish colonies, plagued the southern border. Spain’s refusal to sell Florida changed by 1818 due to its weakened colonial hold after the Peninsular War and growing independence movements in Latin America. With minimal military presence in Florida, Spain struggled to control Seminole raids into U.S. territory and the sanctuary they provided to escaped slaves.

Monroe responded by ordering Andrew Jackson to lead a military expedition into Spanish Florida to combat the Seminoles. Jackson’s forces burned Seminole towns and seized Pensacola, establishing de facto U.S. control. Despite congressional criticism, Monroe, supported by Secretary of State Adams, defended Jackson’s actions and began negotiations with Spain. Spain, unable to manage its American colonies, signed the Adams-Onís Treaty on February 22, 1819. The treaty ceded Florida to the U.S. in exchange for the assumption of $5 million in American claims against Spain. It also defined the boundary between Spanish and American territories, with the U.S. renouncing claims to lands west and south of this boundary, while Spain relinquished claims to the Oregon Country.

South American Wars of Independence

In October 1817, the U.S. cabinet met to address South American independence movements and piracy from Amelia Island. Piracy, fueled by smugglers and privateers fleeing Spanish colonies, troubled the southern border. Initially rejecting U.S. offers to purchase Florida, Spain’s weakened control after the Peninsular War and Latin American revolutions changed its stance by 1818. Spain’s minimal military presence couldn’t manage Seminole raids into U.S. territory or their harboring of escaped slaves.

Monroe ordered Andrew Jackson to lead a military campaign into Spanish Florida against the Seminoles. Jackson’s forces destroyed Seminole towns and captured Pensacola, effectively taking control of the territory. Despite criticism, Monroe, with Secretary of State Adams’ support, defended Jackson’s actions and negotiated with Spain. Overwhelmed by colonial revolts, Spain signed the Adams-Onís Treaty on February 22, 1819, ceding Florida to the U.S. in exchange for the assumption of $5 million in American claims against Spain. The treaty also set the boundary between Spanish and American territories, with the U.S. renouncing claims to lands west and south of this line, and Spain relinquishing claims to the Oregon Country.

Monroe Doctrine

In January 1821, John Quincy Adams first suggested that the American continents should be off-limits to further colonization by foreign powers, an idea that Monroe later embraced. This principle was influenced by the Adams-Onís Treaty and border negotiations in the Oregon Country. Adams emphasized that only Americans should handle colonization in the Americas, excluding Canada. This idea became a key tenet of Monroe’s administration. Following the suppression of the Spanish Revolution of 1820 by France, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun and British Foreign Secretary George Canning warned Monroe about potential European intervention in South America, prompting Monroe to address the future of the Western Hemisphere.

The British, eager to end Spanish colonial restrictions on trade, shared a common interest with the U.S. In October 1823, American minister Richard Rush and Canning discussed a joint stance on possible French intervention in South America. Initially, Monroe was inclined to accept British cooperation. However, Adams opposed this, arguing it could limit U.S. expansion and that the British might have their own imperial motives.

Two months later, the U.S. issued a unilateral declaration instead of a bilateral one. Monroe feared that France or the Holy Alliance might try to control former Spanish territories. On December 2, 1823, in his annual message to Congress, Monroe articulated what became known as the Monroe Doctrine. He reiterated U.S. neutrality in European conflicts, rejected the recolonization of former colonies, and declared the Western Hemisphere closed to new colonization, targeting Russian expansion attempts in the Pacific Northwest.

Domestic Policy: Missouri Compromise

Between 1817 and 1819, Mississippi, Illinois, and Alabama were admitted as new states, exacerbating economic and political tensions between regions. In February 1819, a bill to draft a constitution for Missouri’s statehood sparked intense debate. Congressman James Tallmadge Jr. proposed an amendment to prohibit new slaves in Missouri and free the children of slaves at 25. The bill passed the House but was rejected by the Senate, leading to a deadlock.

In the next session, the House passed a similar bill, allowing Missouri as a slave state. Monroe initially opposed any compromise restricting slavery’s expansion. The issue became complicated with Alabama’s admission as a slave state and Maine’s bid for statehood as a free state. Southern congressmen linked Maine’s and Missouri’s admissions, pressuring the North to accept slavery in Missouri.

The Senate’s compromise excluded slavery from the Louisiana Territory north of the 36°30′ parallel, except in Missouri. Despite his opposition to restricting slavery, Monroe reluctantly signed the Missouri Compromise on March 6, 1820, seeing it as the least harmful option for the South. This temporarily resolved the issue of slavery in the territories, though Monroe’s role in drafting the compromise remains debated.

Internal improvements

As the United States continued to expand, many Americans pushed for internal improvements to aid the country’s development. However, federal support for such projects evolved slowly and inconsistently due to contentious congressional factions and an executive branch wary of unconstitutional federal involvement in state affairs. Monroe believed the young nation needed better infrastructure, including a robust transportation network, to grow and thrive economically. Yet, he did not think the Constitution authorized Congress to build, maintain, and operate a national transportation system. He repeatedly urged Congress to pass an amendment granting it the power to finance internal improvements, but Congress never acted on his proposal. Many congressmen believed the Constitution already permitted federal financing of such projects.

In 1822, Congress passed a bill to collect tolls on the Cumberland Road to fund its repairs. Monroe vetoed the bill, adhering to his position on internal improvements. In a detailed essay, he explained his constitutional views: while Congress could appropriate funds, it could not undertake construction or assume jurisdiction over national works.

In 1824, the Supreme Court ruled in Gibbons v. Ogden that the Constitution’s Commerce Clause allowed the federal government to regulate interstate commerce. Soon after, Congress passed two significant laws marking the start of continuous federal involvement in civil works. The General Survey Act authorized the president to survey routes for roads and canals of national importance, delegating this task to the Army Corps of Engineers. Another act allocated $75,000 to improve navigation on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers by removing obstacles, later expanding to other rivers like the Missouri. This work was also assigned to the Corps of Engineers, the only formally trained engineers in the new republic, available to serve both Congress and the executive branch.

Panic of 1819

At the end of his first term, Monroe confronted an economic crisis known as the Panic of 1819, the first major depression in the United States since the Constitution’s ratification in 1788. The panic arose from declining imports and exports and falling agricultural prices as global markets adjusted to peacetime production and trade following the War of 1812 and the Napoleonic Wars. The severity of the downturn in the U.S. was exacerbated by excessive speculation in public lands and the unchecked issuance of paper money by banks and businesses. Monroe lacked the authority to intervene directly in the economy, as banks were primarily regulated by the states, leaving him with little power to address the crisis.

In response to the economic downturn, cuts had to be made to the federal budget in the following years, primarily impacting defense spending, which had alarmed conservative Republicans by growing to over 35% of the total budget in 1818. Although Monroe’s fortification program initially survived the cutbacks, the standing army’s target size was reduced from 12,656 to 6,000 in May 1819. The next year, the budget for fort construction and reinforcement was slashed by over 70%. By 1821, the defense budget had shrunk to $5 million, about half of what it had been in 1818.

Before the Panic of 1819, some business leaders had urged Congress to raise tariff rates to address the negative balance of trade and support struggling industries. As the panic spread, Monroe declined to call a special session of Congress to address the economy. When Congress reconvened in December 1819, Monroe requested an increase in the tariff but did not recommend specific rates. Congress would not raise tariff rates until the Tariff of 1824 was passed. The panic resulted in high unemployment, increased bankruptcies and foreclosures, and widespread resentment against banking and business enterprises.

Native American policy

Monroe became the inaugural president to explore the American West and delegated Secretary of War Calhoun with overseeing this vast region. To halt the constant assaults on Native American settlements accompanying westward expansion, he proposed dividing the areas between the federal territories and the Rocky Mountains among various tribes for settlement. Each district was to receive its own civil administration and educational system.

Addressing Congress on March 30, 1824, Monroe advocated relocating Native American tribes within U.S. territory to lands west of the frontier where they could maintain their traditional lifestyles. However, he shared Jackson and Calhoun’s concerns regarding independent Native American nations, viewing them as hindrances to the West’s progress. Similar to Washington and Jefferson, Monroe sought to introduce Native Americans to American culture and Western civilization for their welfare and preservation.

Election of 1820

Monroe officially launched his bid for a second presidential term early in his candidacy. At the Republican Caucus on April 8, 1820, all members unanimously decided against nominating any opposing candidate to Monroe. With the collapse of the Federalists by the end of his first term, Monroe faced no organized opposition and ran for reelection unchallenged, a distinction shared only with George Washington in U.S. history.

However, a lone elector from New Hampshire, William Plumer, cast a vote for John Quincy Adams, citing concerns about Monroe’s competence. Later accounts suggested he did so to preserve the honor of George Washington’s unanimous election, though Plumer never explicitly mentioned Washington in his explanation to other New Hampshire electors. Despite his overwhelming support in the presidential election, Monroe had few steadfast allies and consequently limited influence in the concurrent United States Congress.

Post-presidency (1825–1831)

After completing his second term as President in 1825, Monroe retired to his estate in Virginia, known as Oak Hill. Unlike some of his predecessors, Monroe did not seek further political office or engage in public life after leaving the presidency. He spent his post-presidential years primarily focused on managing his plantation and attending to personal affairs.

Monroe’s retirement was marked by financial challenges, exacerbated by his extensive debts incurred during his public service and a decline in his health. Despite these difficulties, he maintained correspondence with friends and colleagues, reflecting on his political career and the state of the nation. Over time, Monroe’s health deteriorated, and he struggled with chronic illness.

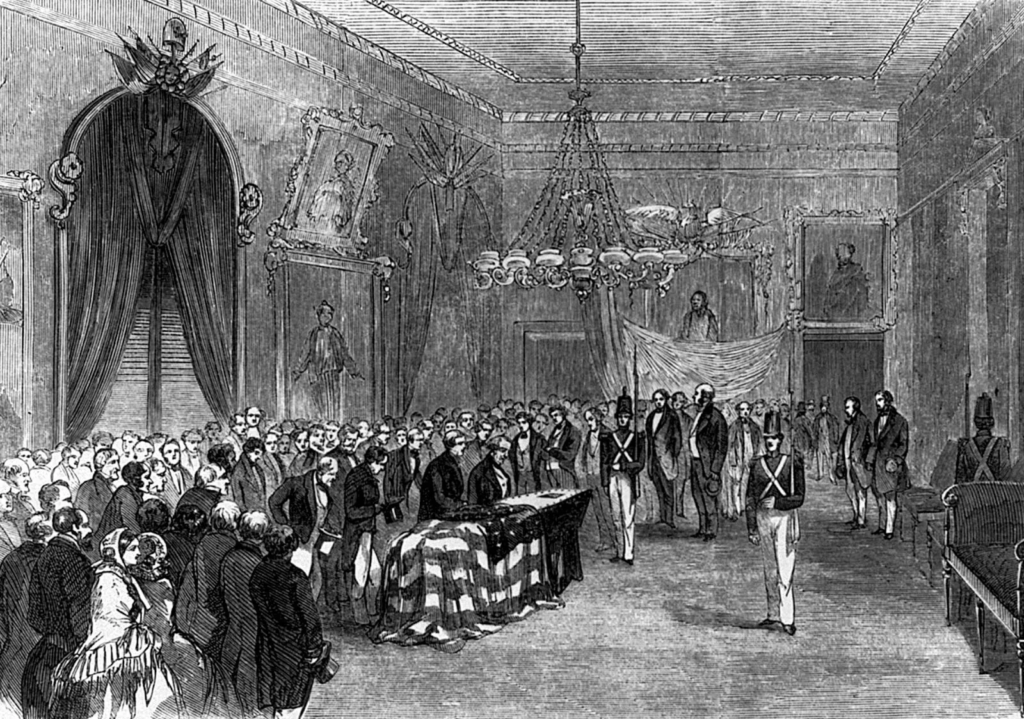

In 1830, Monroe relocated to New York City with his family to seek better medical care. He lived there for a brief period before returning to Virginia in 1831, where he passed away on July 4th of that year at the age of 73. James Monroe was laid to rest at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, leaving behind a legacy shaped by his contributions to American diplomacy, expansion, and national unity during a critical period of the nation’s history.

In retirement, James Monroe faced significant financial troubles. His time as Minister to France in the 1790s had forced him to take out substantial personal loans to cover diplomatic expenses, which were exacerbated by his modest salary. He had long sought reimbursement from Congress for these expenses, starting as early as 1797, but received no payment before his death. In his final days before handing over the presidency to Adams, Monroe appealed to Jefferson and Madison for their support in pressing his claims.

He sold his Highland Plantation to the Second Bank of the United States due to financial necessity, and the property is now owned by his alma mater, the College of William and Mary, and open to the public.

Throughout his life, Monroe struggled with financial insolvency, worsened by his wife’s ongoing health issues. Despite these challenges, he remained active in public life, serving on the Board of Visitors for the University of Virginia under Jefferson and later James Madison, who was the second rector. Monroe’s involvement with the university continued almost until his death, despite having to step back from the board during his presidency. At the university’s annual examinations in July 1830, he chaired the Board of Examiners and recommended the addition of military drill to the curriculum in response to student discipline issues, though this proposal was rejected by Madison.

Despite advancing age and health issues stemming from a serious horse accident in 1828, Monroe was elected as a delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830. Representing his home district of Loudoun and Fairfax County, he was initially chosen as the presiding officer but had to withdraw due to declining health in December 1829.

Religious beliefs

Historian Bliss Isely notes that James Monroe’s religious beliefs remain largely undocumented compared to other presidents. There are no surviving letters where he discusses his views on religion, nor did his friends, family, or associates provide insights on this topic. Correspondence that does exist, including letters after the death of his son, does not touch upon religious matters.

Monroe was raised in a family affiliated with the Church of England during its status as Virginia’s state church before the Revolution. As an adult, he attended Episcopal churches. Some historians interpret his occasional references to an impersonal God as indicative of “deistic tendencies.” Unlike Thomas Jefferson, Monroe was seldom accused of being an atheist or infidel. In 1832, James Renwick Willson, a Reformed Presbyterian minister in Albany, New York, criticized Monroe, stating that he “lived and died like a second-rate Athenian philosopher.

Slavery

Monroe owned numerous slaves, some of whom he brought with him to serve at the White House during his presidency from 1817 to 1825, a practice common among slaveholding presidents.

Having sold his Virginia plantation in 1783 to pursue law and politics, Monroe owned several properties throughout his life, though his plantations were never financially successful. Despite owning extensive land and many slaves, and engaging in property speculation, he was often absent from overseeing operations. Harsh treatment by overseers aimed at maximizing production resulted in plantations that barely broke even. Monroe’s extravagant lifestyle led to accumulating debts, which he occasionally paid off by selling property, including slaves.The labor of his many slaves supported not only Monroe’s household but also his daughter, son-in-law, and his less successful brother, Andrew, along with Andrew’s son, James.

During his tenure as Governor of Virginia in 1800, Monroe faced a significant threat when hundreds of slaves from Virginia planned to kidnap him, seize Richmond, and negotiate for their freedom in what became known as Gabriel’s slave conspiracy.[164] The plot was uncovered, and Monroe responded by calling out the militia. Some accused slaves were captured by slave patrols, and trials, though not fair by modern standards, included some measures to prevent abuses such as the appointment of attorneys.

Monroe influenced the Executive Council to pardon and sell some slaves instead of executing them, a decision supported by a letter from Thomas Jefferson urging mercy to avoid setting a precedent of revenge.[165][166] Ultimately, between 26 and 35 slaves were executed, none for killing whites as the uprising was thwarted before violence ensued. Many others involved in the conspiracy were spared through pardons, acquittals, and commutations influenced by Monroe’s administration.

Throughout his presidency, Monroe maintained the belief that slavery was morally wrong and supported private manumission, yet he opposed any efforts to promote widespread emancipation, fearing it would lead to societal upheaval. He viewed slavery as entrenched in southern society and believed its removal should be left to divine intervention. Like many Upper South slaveholders, Monroe saw maintaining “domestic tranquility” as crucial, viewing government’s role as protecting planters’ interests and preventing potential revolutions akin to those in France and Haiti.[citation needed]

As president of Virginia’s constitutional convention in 1829, Monroe reiterated his condemnation of slavery, tracing its origins to Virginia’s colonial era and lamenting its perpetuation despite early attempts to prohibit further importation of slaves. Despite his support for states’ rights, Monroe was open to federal assistance for emancipation and colonization efforts, proposing at the convention that Virginia use federal aid to emancipate and relocate slaves abroad.

Active in the American Colonization Society, Monroe supported efforts to resettle free African Americans outside the United States. The society facilitated the migration of thousands of freed slaves to Liberia between 1820 and 1840, a project Monroe and other slave owners endorsed to prevent free blacks from inciting rebellion among southern slaves. Liberia’s capital, Monrovia, was named in honor of President Monroe.

Legacy

Monroe’s Legacy

James Monroe’s presidency left a lasting impact on American history, shaping both domestic policies and the nation’s international posture. His legacy is characterized by several key contributions:

- Monroe Doctrine: Perhaps his most enduring legacy, Monroe’s 1823 doctrine asserted U.S. opposition to European intervention in the Americas and declared non-interference in European affairs. This policy set the stage for American dominance in the Western Hemisphere and became a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy.

- Expansion and Nation-Building: Monroe oversaw significant territorial expansions, including the acquisition of Florida and the settlement of numerous border disputes. These actions expanded U.S. territory and solidified its borders, contributing to national unity.

- Era of Good Feelings: Monroe’s presidency was marked by relative political harmony, known as the Era of Good Feelings. Under his leadership, partisan divisions diminished, and Monroe pursued policies that sought to unite the nation after years of political turbulence.

- Missouri Compromise: Monroe played a crucial role in negotiating the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which temporarily resolved tensions over the expansion of slavery in new territories. This compromise helped maintain the delicate balance between free and slave states.

- Infrastructure and Economic Policy: While Monroe faced economic challenges, such as the Panic of 1819, he advocated for internal improvements and infrastructure projects that laid the groundwork for future economic growth and development.

- Legacy of Leadership: Monroe’s tenure as president is often viewed as a period of effective leadership and pragmatic governance. His administration set precedents for presidential authority and diplomacy, influencing subsequent presidents.

Overall, James Monroe’s presidency left a significant imprint on American history, contributing to the nation’s territorial expansion, foreign policy doctrines, and efforts to forge a unified identity during a pivotal period in its development.

Historical Reputation

Monroe is generally regarded favorably among historians and political scientists, often being ranked as an above-average president. His administration marked a turning point for the United States, shifting focus from European affairs to domestic issues. Monroe successfully resolved several longstanding boundary disputes through agreements with Britain and the acquisition of Florida. Additionally, he played a pivotal role in easing sectional tensions by supporting the Missouri Compromise and actively seeking consensus across different regions of the country. Political scientist Fred Greenstein contends that Monroe was a more capable executive compared to some of his more prominent predecessors, such as Madison and John Adams.

Memorials

Monroe’s Legacy

The capital of Liberia, Monrovia, was named after Monroe, making it the only national capital other than Washington, D.C., named after a U.S. president. Additionally, seventeen Monroe counties across the United States bear his name. Several places, including Monroe, Maine; Monroe, Michigan; Monroe, Georgia; Monroe, Connecticut; both Monroe Townships in New Jersey; and Fort Monroe, also honor him. Monroe has been featured on U.S. currency and postage stamps, notably appearing on a 1954 United States Postal Service 5¢ Liberty Issue stamp.

Monroe was notable as the last U.S. president to wear a powdered wig tied in a queue, a tricorne hat, and knee-breeches, adhering to late 18th-century fashion. This earned him the nickname “The Last Cocked Hat”. Additionally, Monroe holds the distinction of being the last president who was not photographed.

Monroe’s role in pivotal moments of the American Revolutionary War, such as George Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River and the Battle of Trenton, was immortalized in Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware” and John Trumbull’s painting “The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, December 26, 1776.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Monroe