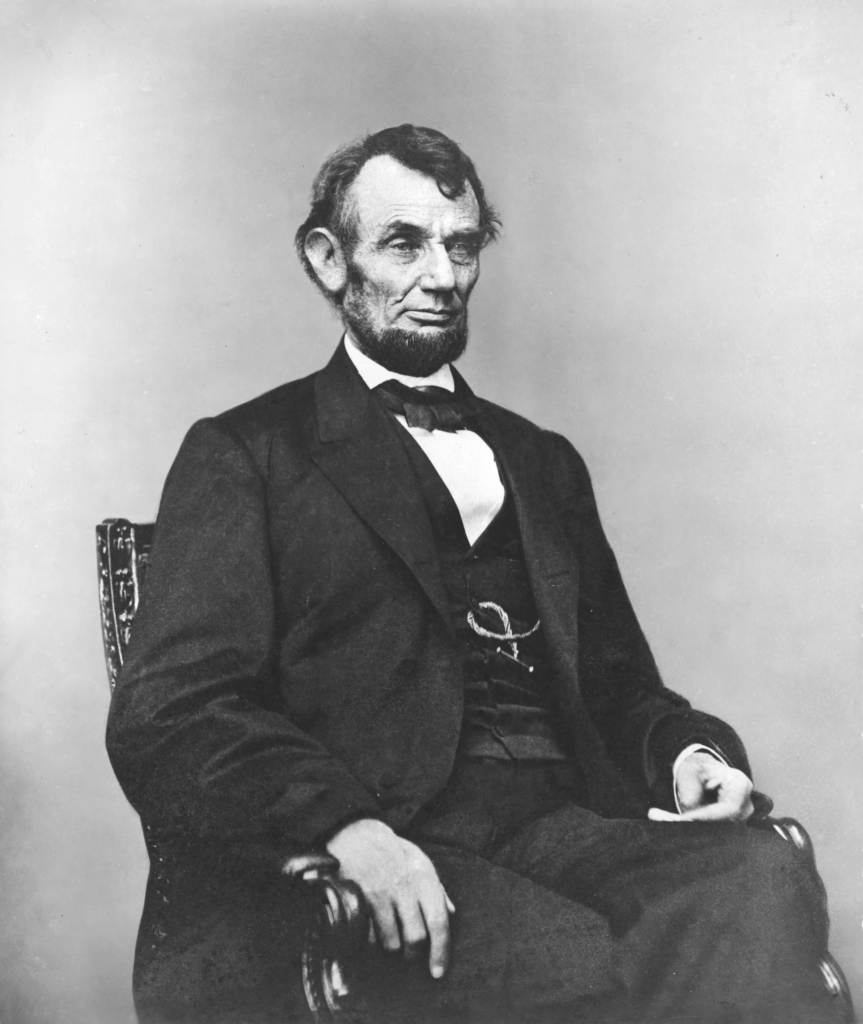

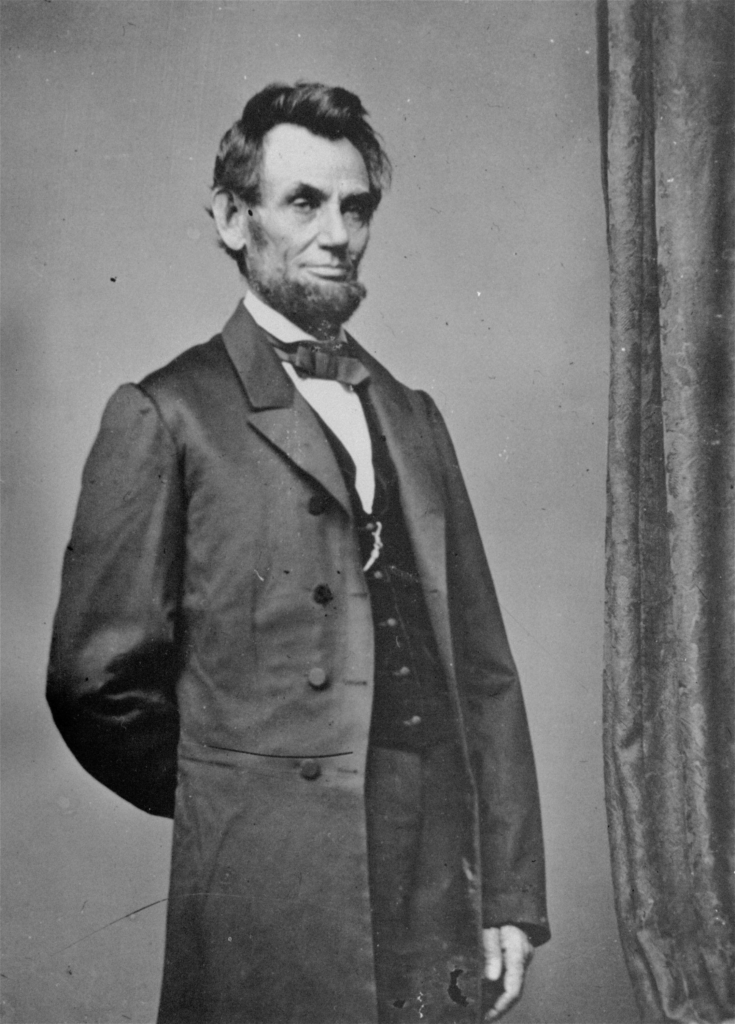

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln guided the country through the American Civil War, preserving the Union, defeating the Confederacy, and playing a crucial role in ending slavery. He also expanded federal power and helped modernize the U.S. economy.

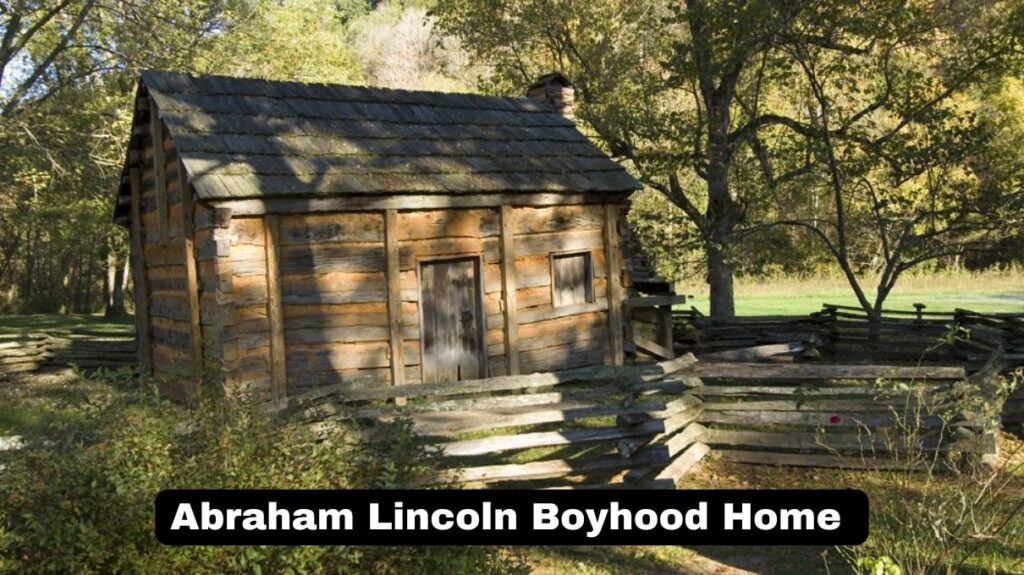

Born in a log cabin in Kentucky to a poor family, Abraham Lincoln was largely self-educated and became a successful lawyer. He initially worked as a Whig Party leader, Illinois state legislator, and U.S. representative. In 1849, he returned to law but re-entered politics in 1854 after the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed slavery in new territories. As a leader of the Republican Party, Lincoln gained national prominence through debates with Stephen A. Douglas and won the presidency in 1860. His election led to Southern states seceding and forming the Confederacy.

Shortly after taking office, Abraham Lincoln faced the attack on Fort Sumter and began mobilizing forces to suppress the rebellion. Balancing various factions within his party and beyond, Lincoln managed both the war effort and domestic politics with skill. He issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, which declared the freedom of slaves in rebellious states, and supported the Thirteenth Amendment to abolish slavery.

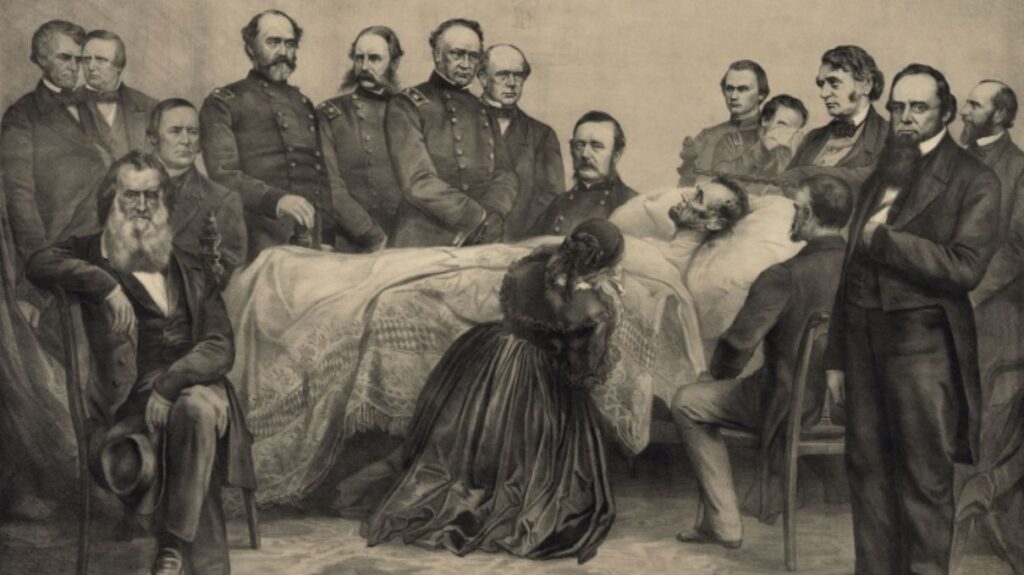

Lincoln was re-elected in 1864 and sought to heal the nation post-war. Tragically, just days after General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre.

Remembered as a martyr and national hero,Abraham Lincoln is frequently regarded as one of America’s greatest presidents for his leadership during a tumultuous time and his efforts to end slavery.

Early Life and Family

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in a log cabin on Sinking Spring Farm near Hodgenville, Kentucky. His family had deep roots in early American history, descending from Samuel Lincoln, an English immigrant who settled in Massachusetts in 1638. Lincoln’s paternal grandfather, Captain Abraham Lincoln, was killed in an Indian raid in 1786, a traumatic event witnessed by his son, Thomas, Abraham’s father.

Thomas Lincoln faced numerous challenges with land ownership and eventually moved his family to Indiana in 1816 for more reliable land titles. They settled in a remote forest area of Perry County, Indiana. Thomas worked various jobs including farming and carpentry, and was actively involved in community and church life. The family’s move to Indiana was influenced partly by issues related to slavery and land disputes.

Mother’s Death and Family Changes

On October 5, 1818, Nancy Lincoln passed away from milk sickness, leaving 11-year-old Sarah to manage the household. The family included her father, Thomas; her nine-year-old brother, Abraham; and Nancy’s 19-year-old cousin, Dennis Hanks. Tragically, ten years later, on January 20, 1828, Sarah died during childbirth, leaving Abraham deeply affected by the loss.

In December 1819, Thomas Lincoln remarried Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow from Elizabethtown, Kentucky, who brought three children of her own into the family. Abraham developed a close bond with his stepmother and affectionately called her “Mother.” Despite some criticism from Dennis Hanks about Abraham’s reluctance for physical labor, Sarah recognized his passion for reading.

Education and move to Illinois

Abraham Lincoln was mostly self-taught. His formal schooling was limited to a few periods with itinerant teachers in Kentucky and Indiana, totaling less than a year by age 15. Despite this, he remained a voracious reader throughout his life. He read widely, including the Bible, Aesop’s Fables, and Robinson Crusoe. His dedication to learning was later recognized with honorary degrees, including one from Columbia University.

As a teenager, Abraham Lincoln took on significant responsibilities on the family farm, and he became known for his strength and skill in wrestling, even becoming a county champion. In March 1830, seeking to avoid another milk sickness outbreak, the Lincoln family moved west to Illinois, settling in Macon County. Abraham grew increasingly distant from his father, partly due to their differing views on education. By 1831, Lincoln set out on his own, settling in New Salem, Illinois, where he worked and witnessed slavery firsthand during a trip to New Orleans.

Abraham Lincoln Marriage and Children

Abraham Lincoln early romantic interests included Ann Rutledge, whom he deeply mourned after her death in 1835, leading to a period of depression. In the early 1830s, he also had a brief engagement with Mary Owens, which ended after both had second thoughts.

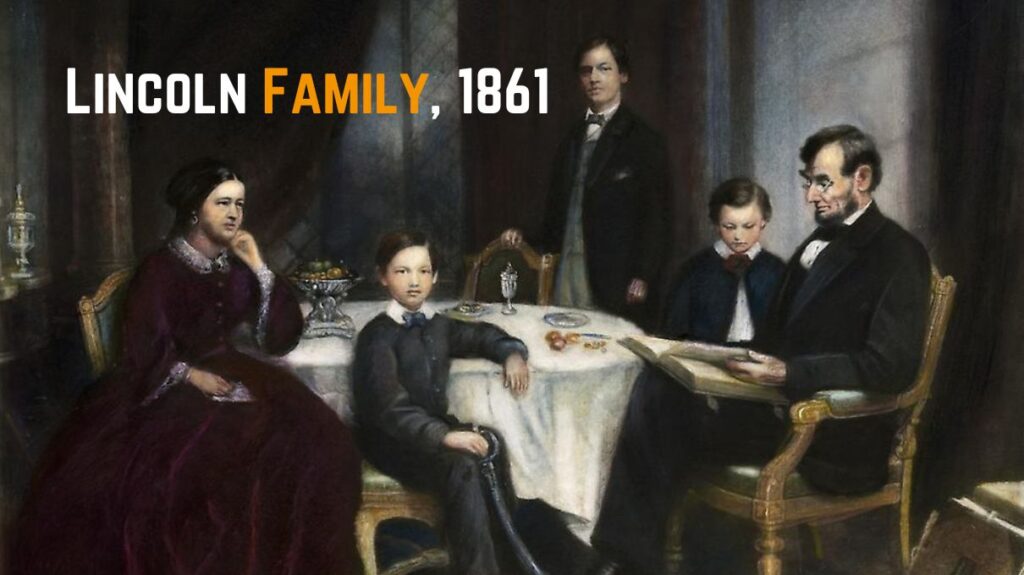

In 1839, Lincoln met Mary Todd in Springfield, Illinois, and they became engaged the following year. Although their initial wedding date was postponed, they married on November 4, 1842. The couple settled in Springfield, where Mary managed the household.

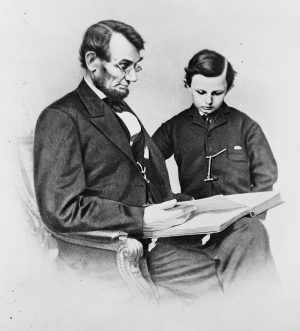

Abraham Lincoln was a loving father to four sons, though his demanding career often kept him away. His eldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, was the only one to survive to adulthood. Edward Baker Lincoln, born in 1846, died in 1850, likely from tuberculosis. “Willie” Lincoln, born in 1850, died of a fever in 1862. The youngest, Thomas “Tad” Lincoln, was born in 1853 and survived his father but died of heart failure in 1871.

Abraham Lincoln was known for his affection towards his children, though his work often absorbed him, leading to occasional tension with his law partner, William Herndon. The deaths of Eddie and Willie profoundly affected Lincoln, who struggled with melancholy, now understood as clinical depression. Mary Todd Lincoln also faced significant emotional distress from these losses, eventually leading to her being committed to an asylum by their surviving son, Robert, in 1875.

Early Career and Militia Service

In 1831 and 1832, Abraham Lincoln worked at a general store in New Salem, Illinois. His budding political aspirations were briefly put on hold when he enlisted as a captain in the Illinois Militia during the Black Hawk War. After his military service,Abraham Lincoln initially planned to become a blacksmith but instead teamed up with 21-year-old William Berry to purchase the New Salem store on credit. To sell beverages legally, they both obtained bartending licenses. In 1833, their store also operated as a tavern.

As licensed bartenders, Abraham Lincoln and Berry sold liquor for 12 cents a pint and provided a range of drinks and food. However, Berry’s struggle with alcoholism meant he was frequently absent, leaving Lincoln to manage the store alone. Despite a booming economy, the business faltered and eventually went into debt, prompting Lincoln to sell his share.

During his first campaign speech after returning from military service,Abraham Lincoln famously defended a supporter from an attacker by physically removing the assailant. His campaign focused on advocating for improvements to the Sangamon River. Despite his engaging speaking style, lack of formal education, influential connections, and financial backing contributed to his loss in the election. Lincoln finished eighth out of thirteen candidates, receiving 277 out of 300 votes in the New Salem precinct.

Abraham Lincoln took on various local roles, including postmaster and county surveyor, while continuing his self-directed study of law. Instead of apprenticing with a lawyer, he borrowed legal texts from local attorneys, bought books like Blackstone’s Commentaries and Chitty’s Pleadings, and taught himself the law. He later remarked that he “studied with nobody.”

Illinois State Legislature (1834–1842)

Abraham Lincoln second run for the state house in 1834, as a Whig, was successful. He served four terms in the Illinois House of Representatives for Sangamon County, where he championed the Illinois and Michigan Canal’s construction and served as a Canal Commissioner. He supported expanding suffrage to all white males and took a “free soil” stance, opposing both slavery and abolition. Abraham Lincoln believed that abolitionist rhetoric could worsen the problem of slavery and supported the American Colonization Society, which proposed relocating freed slaves to Liberia.

Admitted to the Illinois bar in September 1836, Lincoln moved to Springfield and began practicing law with John T. Stuart, Mary Todd’s cousin. He quickly became known for his skills in trial advocacy, working with Stephen T. Logan before partnering with William Herndon in 1844.

On January 27, 1838, Abraham Lincoln delivered a significant speech at the Lyceum in Springfield, addressing the murder of newspaper editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy. He warned that the nation’s destruction would be self-inflicted, not from external forces. The brutal killing of Francis McIntosh in 1836 also influenced Lincoln’s later decision to enter politics.

U.S. House of Representatives (1847–1849)

By 1846, Abraham Lincoln was firmly established as a Whig, supporting Henry Clay’s vision for economic modernization, including banking reforms and internal improvements. Lincoln sought the Whig nomination for Illinois’s 7th district seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and won the election. Despite being the only Whig in Illinois’s delegation, he participated actively in votes and committee work.

Lincoln was assigned to the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads and the Committee on Expenditures in the War Department. He collaborated with Joshua R. Giddings on a bill to end slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for slave owners, though the bill failed to gain Whig support.

On foreign policy, Lincoln opposed the Mexican-American War, critiquing President Polk’s quest for “military glory” and supporting the Wilmot Proviso, which sought to ban slavery in new U.S. territories. His Spot Resolutions challenged Polk to specify the exact location where American blood was spilled, a move that cost him political support and earned him the nickname “spotty Lincoln.”

Abraham Lincoln had pledged to serve only one term in the House. When it became clear that Henry Clay’s presidential bid would fail, Lincoln supported General Zachary Taylor for the 1848 election. Although Taylor won, Lincoln’s hopes for a post were dashed, and he declined offers for distant positions like Secretary or Governor of Oregon, choosing to return to his legal practice.

Prairie Lawyer

As a lawyer in Springfield, Abraham Lincoln handled a wide range of cases. He traveled to county seats twice a year for ten weeks at a time, managing cases related to the nation’s expansion and transportation issues. Notably, he represented clients in landmark cases such as Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company and earned a patent for a flotation device, making him the only U.S. president to hold a patent.

Abraham Lincoln argued before the Illinois Supreme Court in 175 cases, winning 31 of 51 where he served as sole counsel. His reputation for honesty earned him the nickname “Honest Abe.”

One notable case in 1858 involved defending William “Duff” Armstrong, accused of murder. Lincoln used a Farmers’ Almanac to challenge the credibility of an eyewitness, ultimately leading to Armstrong’s acquittal. Another high-profile case in 1859 saw Lincoln successfully argue for the admissibility of a dying declaration in the trial of Simeon Quinn “Peachy” Harrison, enhancing his profile as he prepared for his presidential campaign.

Republican Politics (1854–1860)

Rising as a Republican Leader

By the mid-1850s, the debate over slavery was tearing the nation apart. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed territories to decide the status of slavery through popular sovereignty, only deepened the divide between the North and South. Abraham Lincoln, who had previously supported Henry Clay’s gradual emancipation ideas, now firmly opposed this act. In a notable speech in Peoria, Illinois, in October 1854, Lincoln condemned the Kansas-Nebraska Act for its apparent eagerness to expand slavery and argued against its injustice, which marked his return to political prominence.

The Whig Party, once a major political force, was unraveling under the strain of the slavery debate. Lincoln, reflecting on his shifting political landscape, recognized the emerging Republican Party as a new platform for his anti-slavery views. Although he initially hesitated to join, wary of the party’s potential association with radical abolitionism, Lincoln’s concerns were overshadowed by his commitment to opposing the spread of slavery.

In 1854, Abraham Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature but chose not to serve so he could run for the U.S. Senate. Although he led in initial votes, he didn’t secure a majority. Instead, Lincoln supported Lyman Trumbull, an antislavery Democrat, which ultimately led to Trumbull’s victory over the mainstream Democratic candidate, Joel Aldrich Matteson.

1856 Campaign

The political climate remained volatile, especially in Kansas, where violent clashes continued over the issue of slavery. As the 1856 elections approached, Lincoln formally joined the Republican Party and participated in the Bloomington Convention, which founded the Illinois Republican Party. The convention’s platform advocated for congressional regulation of slavery in the territories and supported Kansas’s admission as a free state. Lincoln’s compelling final speech at the convention underscored his dedication to preserving the Union.

During the 1856 presidential campaign, Lincoln supported the Republican candidate, John C. Frémont, though he did not run himself. The Democrats nominated James Buchanan, who won the election, while Lincoln emerged as a prominent Republican leader in Illinois, with his campaign contributions noted for their effectiveness.

Dred Scott Decision

In 1857, the Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford declared that black people were not citizens and that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. Lincoln denounced the ruling as a politically motivated effort to protect slavery and argued that it contradicted the Declaration of Independence’s principles of equality and inalienable rights.

Lincoln-Douglas Debates and Cooper Union Speech

The 1858 Senate race against incumbent Stephen A. Douglas provided Lincoln with a national stage. The debates between Lincoln and Douglas, renowned for their intensity and public interest, showcased Lincoln’s argument against the expansion of slavery and his critique of Douglas’s stance. Despite losing the Senate seat, Lincoln’s performance in the debates significantly raised his national profile.

On February 27, 1860, Lincoln delivered a pivotal speech at Cooper Union in New York City. His arguments highlighted the Founding Fathers’ opposition to slavery and emphasized the moral imperative to combat it. The speech, though not universally well-received, marked a crucial moment in establishing Lincoln as a serious presidential contender.

1860 Presidential Election

By May 1860, Lincoln had gained substantial backing within the Republican Party. His campaign team effectively utilized his image as a “Rail Splitter” and “Honest Abe” to build support. At the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Lincoln secured the nomination on the third ballot, with Hannibal Hamlin as his vice-presidential running mate.

Despite his limited public campaigning, Lincoln’s team harnessed his reputation and the party’s resources to achieve a successful electoral outcome. Lincoln’s victory in the presidential election was largely supported by northern and western states, reflecting the nation’s divisions. With 180 electoral votes to his opponents’ 123, Lincoln’s election signaled the looming Civil War, as he received no votes in most Southern states and won only two counties in the South.

Presidency (1861–1865)

Secession and Inauguration

Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration as the 16th President of the United States on March 4, 1861, marked the beginning of a tumultuous period. Despite the festive atmosphere, there were growing concerns about the looming conflict. The New York Times headlines hinted at the tensions, which soon escalated when the Confederate Army attacked Fort Sumter just six weeks later, igniting the American Civil War.

The South, enraged by Lincoln’s election, hastened their secession from the Union even before he officially took office. South Carolina led the charge on December 20, 1860, and by February 1, 1861, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had joined in. These states formed the Confederate States of America and adopted their own constitution.

Meanwhile, upper South and border states like Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas initially rejected the secessionist movement. Both President Buchanan and President-elect Abraham Lincoln declared the Confederacy’s actions illegal. Jefferson Davis was appointed as the provisional president of the Confederacy on February 9, 1861.

Despite efforts at compromise, Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans rejected the Crittenden Compromise, which aimed to protect slavery in existing states. Lincoln firmly stated, “I will suffer death before I consent to any concession or compromise which looks like buying the privilege to take possession of this government to which we have a constitutional right.”

Abraham Lincoln also supported the Corwin Amendment to the Constitution, designed to protect slavery where it existed. By the time Lincoln assumed office, this amendment was awaiting ratification. In his first inaugural address, Abraham Lincoln expressed his willingness to make such protections explicit, if necessary, while reassuring the South that he had no intention of interfering with slavery where it was already established.

Abraham Lincoln journey to Washington was fraught with danger due to secessionist plots. Traveling under heavy security and in disguise, he successfully reached the capital on February 23, 1861, where he faced a divided nation. His inaugural address aimed to calm Southern fears, emphasizing his lack of intent to abolish slavery in the Southern states. He highlighted the core conflict as the extension of slavery into new territories and concluded with a plea for unity.

Despite Abraham Lincoln efforts, the Peace Conference of 1861 failed to prevent the inevitable conflict. By March 1861, no compromise proposals had emerged, and the disintegration of the Union seemed unavoidable.Abraham Lincoln second inaugural address would later reflect on the inevitability of the war, stating, “Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the Nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish.”

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

- 13th President of the United States

- 14th President of the United States

- 15th President of the United States

- 16th President of the United States

- 17th President of the United States

- 18th President of the United States

- 19th President of the United States

Civil War

The Civil War began in earnest on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter. Abraham Lincoln call for 75,000 volunteer troops on April 15, 1861, to suppress the rebellion and restore the Union polarized the nation. Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas seceded in response. The attack on Fort Sumter unified Northern resolve to defend the Union.

Abraham Lincoln administration faced early setbacks, including a violent encounter with mobs in Baltimore and subsequent suspension of habeas corpus to protect troop movements. This controversial decision led to a significant legal and political debate. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney ruled against Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus in Ex parte Merryman, though Lincoln continued with selective suspension.

Abraham Lincoln took a hands-on approach to military strategy, expanding his war powers and imposing a blockade on Confederate ports. His leadership was characterized by a delicate balance of military strategy and political maneuvering. The appointment of generals and the handling of the War Department were crucial to his strategy. The Confiscation Act of 1861 and the subsequent Confiscation Act of 1862 marked early steps towards emancipation, although their immediate impact was limited.

Internationally, Lincoln worked to prevent foreign intervention on behalf of the Confederacy, navigating crises such as the Trent Affair with Britain. Domestically, he faced criticism from both Copperheads and Radical Republicans. His administration was marked by significant changes in military leadership, including the removal of General George B. McClellan and subsequent appointments of Generals like Ambrose Burnside and Joseph Hooker.

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, was a pivotal moment in Abraham Lincoln presidency. Initially, Lincoln had been cautious, seeking to avoid alienating border states and emphasizing the preservation of the Union over emancipation. However, as the war progressed, he issued the proclamation freeing slaves in states still in rebellion, significantly shifting the war’s moral and political landscape.

Gettysburg Address (1863)

On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the most iconic speeches in American history at the dedication of the Gettysburg battlefield cemetery. In just 272 words, spoken in about three minutes, Lincoln redefined the purpose of the Civil War. He argued that the United States was not just founded in 1789, but in 1776, with a commitment to the principle that “all men are created equal.”

Abraham Lincoln emphasized that the war was about preserving a nation dedicated to liberty and equality for everyone. He assured that the sacrifices made by soldiers would not be in vain and that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” Despite his initial belief that the speech would be largely forgotten, it became one of the most quoted addresses in American history.

Promoting General Grant

President Abraham Lincoln was deeply impressed by General Ulysses Grant’s successes in the Battle of Shiloh and the Vicksburg campaign. Despite criticism of Grant’s performance at Shiloh, Lincoln famously declared, “I can’t spare this man. He fights.” Lincoln saw Grant as key to advancing the Union Army’s efforts and including black troops in the fight. When General George Meade failed to capture General Robert E.

Lee’s army after Gettysburg, Lincoln promoted Grant to the supreme commander of all Union forces. Concerned that Grant might be eyeing the presidency, Lincoln ensured Grant had no such ambitions before promoting him to Lieutenant General, a rank that had been vacant since George Washington. Grant’s relentless pursuit of victory, despite heavy losses, played a crucial role in the Union’s ultimate success. Lincoln authorized Grant to target Southern infrastructure to weaken the South’s morale and military capabilities. Grant’s strategy and the Union’s persistence eventually led to General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, bringing the war to an end.

Reelection

In the 1864 presidential election, Lincoln sought reelection while uniting the Republican factions and War Democrats. To broaden his support, he ran under the newly formed Union Party banner with Andrew Johnson as his vice-presidential candidate. Despite concerns about Grant’s costly battles and the possibility of defeat, Lincoln privately pledged to continue fighting the Confederacy even if he lost the election.

The Democratic Party’s platform, which criticized the war, did not align with their candidate, General George McClellan, who supported it. Lincoln’s strategic victories, including General William Tecumseh Sherman’s capture of Atlanta and Admiral David Farragut’s victory at Mobile Bay, bolstered his reelection chances. On November 8, 1864, Lincoln won a decisive victory, securing the support of 78 percent of Union soldiers.

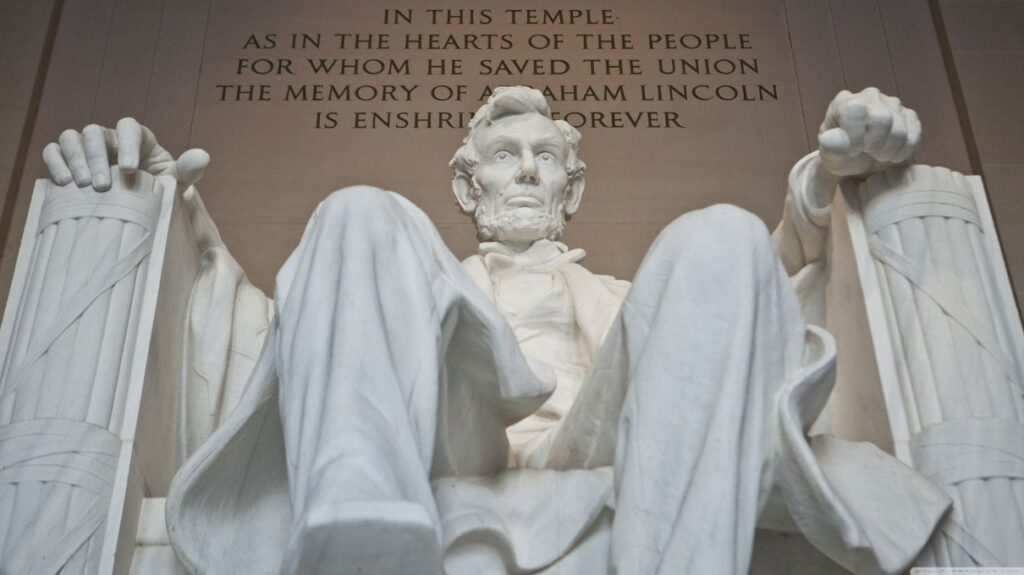

On March 4, 1865, Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address, expressing hope for a swift end to the war while acknowledging that it might continue until justice was served. He called for healing and rebuilding the nation, emphasizing charity, firmness in righteousness, and a commitment to peace. The speech, considered one of America’s semi-sacred texts, is inscribed in the Lincoln Memorial. Tragically, just over a month later, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth.

Reconstruction

As the Civil War neared its end, Lincoln began to focus on the reintegration of the Southern states and the future of freed slaves. His approach was to reconcile rather than punish, aiming to bring the nation back together without laying blame. Abraham Lincoln Reconstruction policy faced opposition from Radical Republicans who sought more drastic changes. Lincoln advocated for a swift restoration of statehood under generous terms, exemplified by his Amnesty Proclamation of December 8, 1863, which offered pardons to those who pledged allegiance to the Union.

As Southern states fell under Union control, Lincoln appointed military governors and sought to establish new state governments. Despite accusations of political maneuvering and criticism from Radicals, Lincoln’s approach emphasized reconciliation and rebuilding. He championed the Thirteenth Amendment to end slavery, which passed Congress and was ratified as law on December 6, 1865.

Abraham Lincoln handling of Reconstruction remains a topic of historical debate. While he is believed to have leaned towards a more moderate approach compared to his successor, Andrew Johnson, he was open to adapting his policies based on evolving needs and pressures. His legacy in Reconstruction is marked by his efforts to balance justice and reconciliation while laying the groundwork for the nation’s recovery.

Native Americans

Abraham Lincoln interactions with Native Americans were shaped by both his personal history and political strategy. His grandfather’s death at the hands of Native Americans and his own service during the Black Hawk War influenced his perspective. His administration faced challenges in protecting Western settlers and infrastructure from Native American attacks.

During the Dakota War of 1862, Lincoln responded to the conflict with a combination of military and diplomatic measures. Despite initial fears of a Confederate conspiracy, Lincoln focused on managing the uprising without further inflaming tensions. He received offers of support from Native American groups but ultimately did not engage them in the conflict against the Sioux. Lincoln’s administration conducted trials for those involved in the war, resulting in a controversial mass execution of 38 Dakota men, the largest such event in U.S. history. Lincoln’s decisions reflected his complex position as he balanced justice, military strategy, and political considerations.

Whig Theory of the Presidency

Abraham Lincoln followed the Whig theory of the presidency, which emphasized the president’s role in enforcing laws while deferring to Congress on legislative matters. During his presidency, Lincoln vetoed only four bills, one of which was the Wade-Davis Bill, known for its stringent Reconstruction measures. Significant legislative achievements during his term included the 1862 Homestead Act, which made vast tracts of Western land available for purchase at minimal cost, and the 1862 Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act,

which provided federal grants for agricultural colleges in every state. Additionally, the Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864 supported the construction of the first transcontinental railroad in the United States, completed in 1869. These landmark acts were made possible by the absence of Southern lawmakers who had previously opposed such measures.

The Lincoln Cabinet

| Office | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| President | Abraham Lincoln | 1861–1865 |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin | 1861–1865 |

| Andrew Johnson | 1865 | |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Salmon P. Chase | 1861–1864 |

| William P. Fessenden | 1864–1865 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron | 1861–1862 |

| Edwin M. Stanton | 1862–1865 | |

| Attorney General | Edward Bates | 1861–1864 |

| James Speed | 1864–1865 | |

| Postmaster General | Montgomery Blair | 1861–1864 |

| William Dennison Jr. | 1864–1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Caleb Blood Smith | 1861–1862 |

| John Palmer Usher | 1863–1865 |

Abraham Lincoln strategically chose his cabinet members, including former rivals, to strengthen his administration. He believed that using the best minds available, regardless of political affiliations, was crucial for the nation’s well-being. As Lincoln remarked, he sought out the strongest individuals to maintain unity and avoid depriving the country of their talents. Doris Kearns Goodwin famously described Lincoln’s cabinet as a “Team of Rivals.”

To fund the federal government, Lincoln implemented two key revenue measures: tariffs and a federal income tax. He signed the second and third Morrill Tariffs in 1861, following Buchanan’s first tariff. Lincoln also enacted the Revenue Act of 1861, introducing the first U.S. income tax—a 3% flat tax on incomes exceeding $800 (approximately $27,129 in today’s currency). The Revenue Act of 1862 revised these rates to be progressive.

Lincoln’s administration also marked the expansion of federal economic influence. The National Banking Act established a system of national banks, and the U.S. introduced paper currency, known as greenbacks. In 1862, Congress created the Department of Agriculture.

Amid rumors of a new draft, the New York World and the Journal of Commerce falsely claimed a draft proclamation to manipulate the gold market. Lincoln responded by seizing the papers for two days and condemning their deceitful actions.

Thanksgiving Proclamation (1863)

Abraham Lincoln is credited with establishing Thanksgiving as a national holiday. Although Thanksgiving had been a regional holiday in New England since the 17th century, it was not consistently observed. The last federal proclamation had been made during James Madison’s presidency fifty years earlier. In 1863, Lincoln declared the final Thursday in November as a day of Thanksgiving.

In June 1864, Lincoln approved the Yosemite Grant, which provided unprecedented federal protection for what would become Yosemite National Park.

Supreme Court Appointments

| Justice | Nominated | Appointed |

|---|---|---|

| Noah Haynes Swayne | January 21, 1862 | January 24, 1862 |

| Samuel Freeman Miller | July 16, 1862 | July 16, 1862 |

| David Davis | December 1, 1862 | December 8, 1862 |

| Stephen Johnson Field | March 6, 1863 | March 10, 1863 |

| Salmon Portland Chase (Chief Justice) | December 6, 1864 | December 6, 1864 |

Abraham Lincoln approach to Supreme Court nominations was to select individuals with known opinions, avoiding the need to question their future actions. He made five appointments to the Supreme Court: Noah Haynes Swayne, a Unionist lawyer; Samuel Freeman Miller, an abolitionist; David Davis, his 1860 campaign manager and Illinois judge; Stephen Johnson Field, a former California Supreme Court justice; and Salmon P. Chase, whom Lincoln believed would support Reconstruction and unify the Republican Party.

Foreign Policy

Abraham Lincoln primarily relied on his Secretary of State, William H. Seward, to manage foreign affairs. Seward’s major challenge was preventing Britain and France from supporting the Confederacy. By threatening war with these nations, Seward succeeded in keeping them neutral.

Assassination

John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer and actor, plotted to assassinate Lincoln after a public address where Abraham Lincoln expressed support for extending voting rights to some African Americans. Booth initially planned to kill Lincoln and General Grant at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865. However, Grant decided to visit his children, leaving Lincoln and his wife to attend the play “Our American Cousin.” Booth entered the theater box and shot Lincoln in the head. After a brief struggle with Major Henry Rathbone, Booth fled but was later tracked down and killed by Sergeant Boston Corbett.

Lincoln was taken to Petersen House, where he died the following morning. His body was displayed in state at the White House and Capitol Rotunda before being transported on the Lincoln Special funeral train to Springfield, Illinois. The train journey allowed for public mourning across the country. Lincoln was buried at Oak Ridge Cemetery, now part of the Lincoln Tomb.

Two weeks after the assassination, Booth was killed during a standoff with Union troops. Initially arrested for disobeying orders, Sergeant Corbett was later exonerated by Secretary of War Stanton.

Religious and Philosophical Beliefs

Abraham Lincoln, portrayed here by George Peter Alexander Healy in 1869, had a complex relationship with religion. As a young man, he was skeptical about organized religion, though he was deeply acquainted with the Bible and often quoted it. Despite his knowledge and respect for religious beliefs, Lincoln never clearly defined his own Christian faith.

Throughout his career, Lincoln frequently used religious language and referenced Scripture, especially in his major speeches like the House Divided Speech, the Gettysburg Address, and his second inaugural address. These speeches often alluded to divine Providence and quoted biblical verses.

In the 1840s, Lincoln adhered to the Doctrine of Necessity, believing that a higher power controlled human destiny. After the death of his son Edward in 1850, Lincoln’s reliance on God became more pronounced. Although he never formally joined a church, he regularly attended services at First Presbyterian Church with his wife starting in 1852.

By the 1850s, Lincoln’s belief in “providence” became more apparent. He rarely used evangelical language, instead holding the Founding Fathers’ republicanism in high regard. The loss of his son Willie in 1862 deepened his questioning of the war’s harshness, pondering why a just God allowed such suffering. Lincoln mused that God could have resolved the conflict without human intervention but chose not to, leaving him to seek answers in the midst of the ongoing struggle.

By 1865, Lincoln’s belief in an omnipotent God was evident in his speeches. He openly acknowledged that historical events were beyond his control and attributed them to divine will. In a letter to a Kentucky newspaper editor in April 1864, Lincoln reflected on the nation’s condition, attributing its state to God’s will and hoping that history would recognize the justice and goodness of God in the resolution of the nation’s issues.

Abraham Lincoln spirituality is vividly illustrated in his second inaugural address, which he regarded as one of his greatest speeches. In it, he framed the war as a manifestation of divine will and frequently used religious imagery to resonate with his predominantly evangelical audience. He even expressed a desire to visit the Holy Land on the day of his assassination.

Health

Abraham Lincoln health was marked by struggles with depression, smallpox, and malaria. He took blue mass pills containing mercury to treat constipation, which might have contributed to mercury poisoning. Claims about his declining health before the assassination, including weight loss and possible genetic conditions like Marfan syndrome or multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B, add to the mystery surrounding his final years.

Legacy

Abraham Lincoln impact on republican values and his role in redefining them are widely acknowledged. He revered the Declaration of Independence as the cornerstone of republicanism, especially at a time when the Constitution’s tolerance of slavery was a major political issue. Historians emphasize that Lincoln’s moral vision and dedication to liberty and equality shaped his legacy.

Lincoln’s approach to the Civil War, based on constitutional arguments and national duty, influenced both Northern soldiers and religious leaders who saw the fight as a moral and divine mission. As a Whig activist, he championed business interests and infrastructure while maintaining a deep admiration for Andrew Jackson’s patriotism.

His legacy continues to evolve. In the 21st century, Lincoln is frequently cited as a favorite president by figures like Barack Obama. His legacy is also marked by global admiration, with notable figures such as Karl Marx, Mahatma Gandhi, and Muammar Gaddafi acknowledging his influence.

Memory and Memorials

Abraham Lincoln memory is preserved in numerous ways. His portrait appears on the penny and the $5 bill, and he is commemorated through countless memorials. Notable among these are the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., and Mount Rushmore, where his likeness stands alongside other iconic presidents. The USS Abraham Lincoln and various other landmarks across the U.S. honor his legacy. In 2019, Congress dedicated a room in the Capitol to Lincoln, recognizing his service as a representative and his lasting impact on American history.