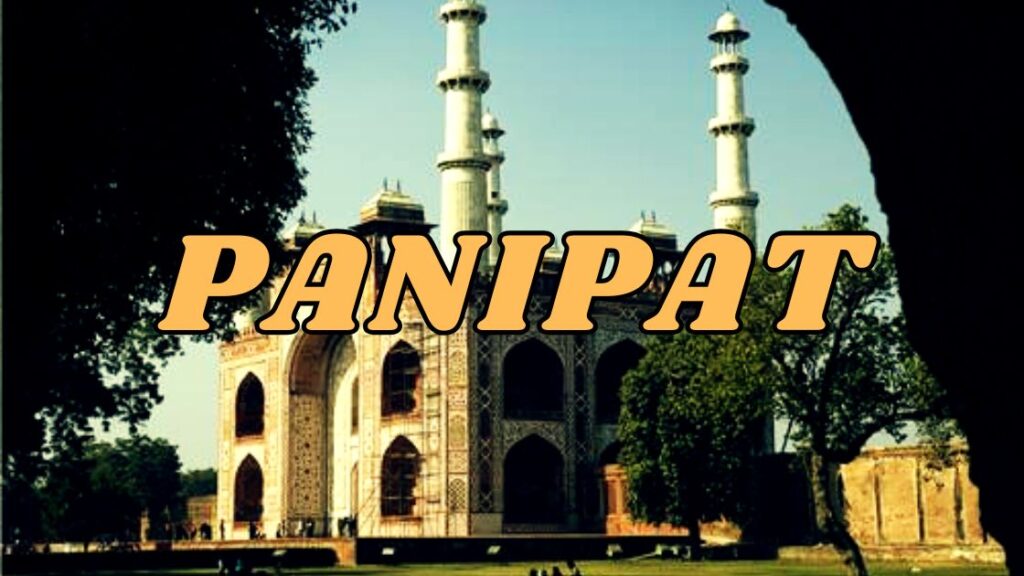

Ulysses S. Grant, originally named Hiram Ulysses Grant, was born on April 27, 1822, and passed away on July 23, 1885. He was a significant figure in American history, serving as both a military leader and the 18th President of the United States, holding office from 1869 to 1877. As the commanding general of the Union Army, Grant played a crucial role in leading the North to victory during the Civil War in 1865. He also briefly held the position of U.S. Secretary of War. As president, Grant was committed to civil rights, signing legislation to establish the Department of Justice and working closely with Radical Republicans to protect the rights of African Americans during Reconstruction.

Grant was born in Ohio and graduated from West Point in 1843. He distinguished himself during the Mexican-American War but left the army in 1854 to return to civilian life, struggling with financial difficulties. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Grant rejoined the Union Army, quickly rising to prominence by securing key victories in the western theater. His leadership during the 1863 Vicksburg campaign was particularly notable, as it gave the Union control of the Mississippi River and dealt a significant blow to the Confederacy.

Following his victory at Chattanooga, President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general. Over thirteen months, Grant engaged in the brutal Overland Campaign against Robert E. Lee, which culminated in Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson promoted Grant to General of the Army, but Grant later distanced himself from Johnson over disagreements on Reconstruction policies. As a celebrated war hero, Grant was unanimously nominated by the Republican Party and won the presidency in 1868.

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the US war (topicsxpress.com)

During his presidency, Grant focused on stabilizing the post-war economy, supporting Congressional Reconstruction, and enforcing the Fifteenth Amendment. He took a strong stand against the Ku Klux Klan and played a key role in restoring the Union. Grant also made significant strides in civil service reform, appointing African Americans and Jewish Americans to important federal positions and establishing the first Civil Service Commission in 1871. Despite his success in these areas, his second term was marred by scandals and his ineffective response to the Panic of 1873, which contributed to the onset of the Long Depression and the Democrats gaining control of the House in 1874.

Grant’s policy toward Native Americans focused on their assimilation into Anglo-American culture, and his foreign policy achievements included the peaceful resolution of the Alabama Claims against Britain. However, his attempt to annex Santo Domingo was rejected by the Senate. Grant played a key role in facilitating a peaceful compromise during the disputed 1876 presidential election.

After leaving office in 1877, Grant embarked on a world tour, becoming the first U.S. president to travel around the globe. Though he unsuccessfully sought a third presidential term in 1880, he remained a respected figure. In 1885, facing financial difficulties and battling throat cancer, Grant wrote his memoirs, which were published posthumously to critical and financial success. At the time of his death, Grant was widely regarded as a symbol of national unity.

However, his reputation suffered in the early 20th century due to the Lost Cause mythology promoted by Confederate sympathizers. In recent years, historians have re-evaluated Grant’s legacy, recognizing his commitment to civil rights, his efforts to secure the Union, and his reformist cabinet appointments, while acknowledging the challenges of his presidency.

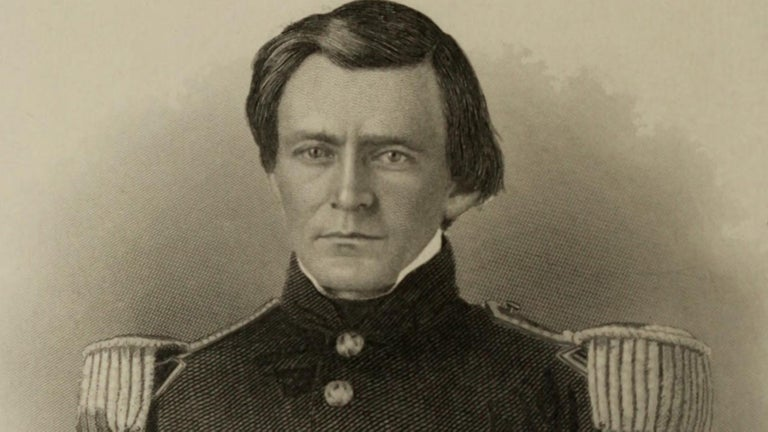

Early Life and Education Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was born Hiram Ulysses Grant on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio. His father, Jesse Root Grant, a staunch Whig and abolitionist, named him after drawing the name “Ulysses” from a hat, though he called him “Ulysses” in honor of his father-in-law. The family moved to Georgetown, Ohio, in 1823, where Grant grew up alongside his five siblings: Simpson, Clara, Orvil, Jennie, and Mary.

At just five years old, Ulysses began attending a subscription school and later went to two private schools. During the winter of 1836–1837, he was enrolled at Maysville Seminary, followed by John Rankin’s academy in the fall of 1838. Grant exhibited a remarkable talent for riding and handling horses, which his father put to use by having him drive wagons and transport goods. Unlike his siblings, Grant was not pressured to attend church by his Methodist parents.

He continued to pray privately and never formally joined any religious group, which led some, including his son, to view him as agnostic. Politically, Grant was relatively indifferent before the Civil War but noted that had he held political views, they would have aligned with the Whigs due to his upbringing.

Early Military Career and Personal Life

In the spring of 1839, Jesse Grant requested Representative Thomas L. Hamer to nominate Ulysses for the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Grant was accepted into the academy on July 1, 1839, but due to a clerical mistake, his name was recorded as “U. S. Grant,” which led to him being nicknamed “Sam” by his fellow cadets, as the initials “U.S.” also stood for “Uncle Sam.”

Grant initially showed little enthusiasm for military life but grew to appreciate his time at West Point and later remarked that he grew to like the academy overall. He gained a reputation as an excellent horseman and took up painting under the guidance of Romantic artist Robert Walter Weir, creating nine surviving pieces.

Although he spent more time on leisure reading than on his studies, he found the mandatory Sunday church services at the academy burdensome. Grant formed close friendships with a few cadets, including Frederick Tracy Dent and James Longstreet, and was influenced by both Captain Charles Ferguson Smith and General Winfield Scott, who visited the academy. Reflecting on his military experience, Grant noted, “there is much to dislike, but more to like.

Graduating on June 30, 1843, ranked 21st in his class of 39, Grant was promoted to brevet second lieutenant the following day. He planned to resign after his initial four-year term, and later in life, he regarded his departure from the presidency and the academy as among his happiest moments. Although Grant was a skilled horseman, he was assigned to the 4th Infantry Regiment rather than the cavalry. His first posting was at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri, the largest military base in the West at the time, commanded by Colonel Stephen W. Kearny. Grant was content with his commanding officer but looked forward to completing his service and possibly pursuing a teaching career.

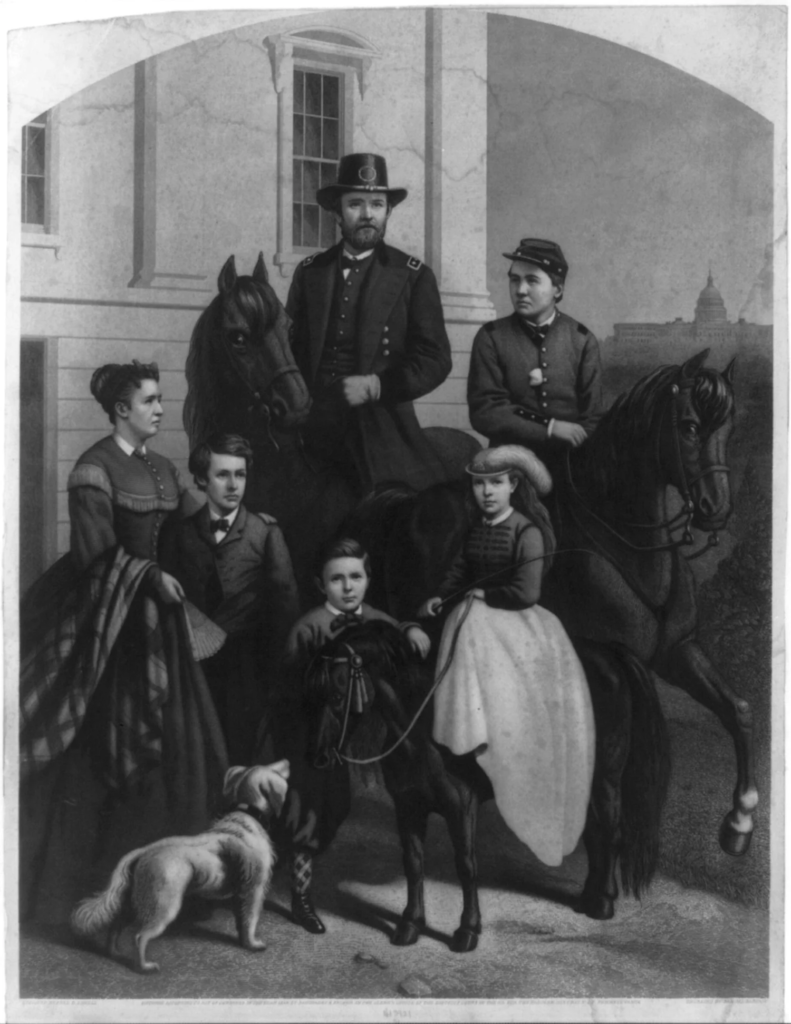

Marriage and Family

In 1844, Ulysses S. Grant visited Missouri with his friend Frederick Dent and met Dent’s family, including his sister, Julia. Grant and Julia quickly became engaged, and they married on August 22, 1848, at Julia’s home in St. Louis. Grant’s father, Jesse, disapproved of the Dents’ slave ownership, which led to both of Grant’s parents missing the wedding. The ceremony featured three of Grant’s West Point classmates in uniform, including James Longstreet, Julia’s cousin.

The Grants had four children: Frederick, Ulysses Jr. (often called “Buck”), Ellen (known as “Nellie”), and Jesse II. After their marriage, Grant extended his leave by two months and returned to St. Louis, where he decided to remain in the army to support his new family.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

- 13th President of the United States

- 14th President of the United States

- 15th President of the United States

- 16th President of the United States

- 17th President of the United States

- 18th President of the United States

- 19th President of the United States

Mexican–American War

During the Mexican American War, Ulysses S. Grant unit was stationed in Louisiana as part of Major General Zachary Taylor’s Army of Occupation. In September 1846, Taylor was ordered to advance to the Rio Grande. Ulysses S. Grant saw combat for the first time at the Battle of Palo Alto on May 8, 1846, while serving as regimental quartermaster. Eager for a direct combat role, Grant participated in a charge at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma and demonstrated his equestrian skills during the Battle of Monterrey by volunteering to deliver a dispatch under fire.

When President Polk, wary of Taylor’s rising popularity, divided the forces, Grant’s unit joined a new army under Major General Winfield Scott. Scott’s troops landed at Veracruz and advanced towards Mexico City, encountering Mexican forces at the battles of Molino del Rey and Chapultepec. Grant earned a brevet promotion to first lieutenant for his bravery at Molino del Rey and was later promoted to captain for his actions at San Cosmé, where he directed a field piece to bombard enemy troops. Scott’s army captured Mexico City on September 14, 1847, and Mexico ceded vast territories to the U.S. on February 2, 1848.

Ulysses S. Grant experiences in the war, where he developed a solid record as a brave and capable officer, influenced his understanding of military leadership. Although he respected Scott, he identified more with Taylor’s style. Grant later considered the war morally unjust, seeing it as a precursor to the Civil War. His role as an assistant quartermaster during the conflict, although initially disliked, was crucial in teaching him about military logistics and supply chains.

Post-War Assignments and Resignation

After the war, Ulysses S. Grant and Julia were stationed in Detroit on November 17, 1848, but soon moved to Madison Barracks, New York, a remote and poorly equipped outpost. Following a brief stint in Detroit, Grant was sent to reinforce the garrison in California during the gold rush. He traveled with soldiers and civilians from New York City to Panama, where he managed a field hospital during a cholera outbreak and personally attended to many patients. He arrived in San Francisco in August and was subsequently assigned to Vancouver Barracks in the Oregon Territory.

Grant’s attempts at various business ventures failed, including one where his partner absconded with $800 of his money. Initially reassured about local Native Americans, Grant’s perspective changed after witnessing their exploitation and suffering. Promoted to captain on August 5, 1853, Grant was assigned to Fort Humboldt in California. His struggles with alcohol led to a reprimand and his resignation on July 31, 1854. Although not court-martialed, Grant’s decision to resign was influenced by his drinking problems. He returned to St. Louis to rejoin his family, facing financial instability.

Civilian Struggles, Slavery, and Politics

Upon leaving the army in 1854, Ulysses S. Grant faced several years of financial hardship and instability. His father offered him a position in the Galena, Illinois branch of the family leather business, but insisted that Julia and the children stay elsewhere, which Grant declined. He tried farming with limited success and resorted to selling firewood to make ends meet.

In 1856, the Grants moved to land on Julia’s father’s farm and built a modest home called “Hardscrabble.” Despite financial struggles, they managed to get by, though Grant once had to pawn his gold watch to buy Christmas gifts. After a bout with malaria and the farm’s lack of success, Grant gave up farming in 1858.

That year, Ulysses S. Grant acquired a slave, William Jones, from his father-in-law. Although not an abolitionist at the time, Grant freed Jones in March 1859, showing his discomfort with slavery. Grant then took a partnership in a real estate business, which also failed, and applied unsuccessfully for a county engineer position due to perceived political biases.

In April 1860, Grant and his family moved to Galena, Illinois, where he joined his father’s leather goods business, “Grant & Perkins.” This move helped him clear his debts and reestablish himself as a respected member of the community.

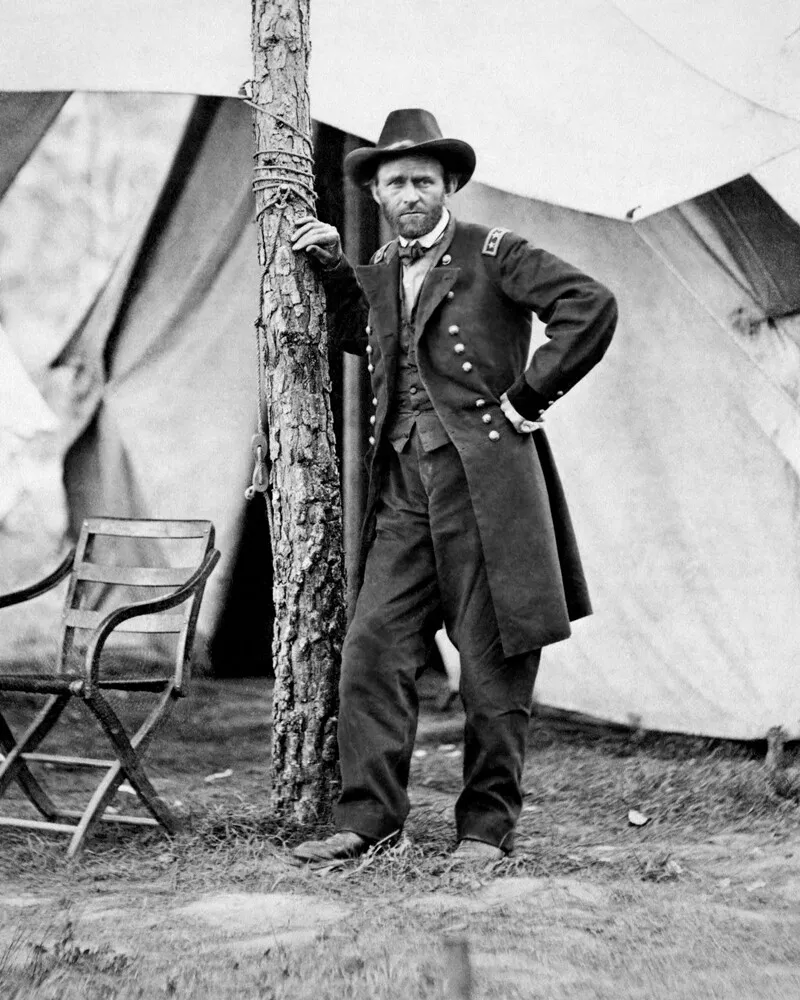

Civil War

The American Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. The news of the attack was a shock to residents of Galena, and Ulysses S. Ulysses S. Grant, like many others, was deeply concerned about the conflict. President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers on April 15 galvanized Grant, who attended a mass meeting the next day to discuss the crisis and promote recruitment. A speech by John Aaron Rawlins, his father’s attorney, sparked Grant’s patriotism, and in a letter to his father on April 21, Ulysses S. Grant expressed his commitment to supporting the government and its flag, stating, “There are but two parties now, Traitors and Patriots.”

Early Commands

In April 1861, Ulysses S. Grant chaired another recruitment meeting but declined a captain’s position, hoping to secure a higher rank based on his experience. Initially, his attempts to be recommissioned were unsuccessful, with Major General George B. McClellan and Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon rejecting his applications. However, on April 29, with support from Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, Grant was appointed military aide to Illinois Governor Richard Yates, helping to organize ten regiments into the Illinois militia.

By June 14, Grant had been promoted to colonel and was given command of the 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, where he implemented strict discipline and brought order to the unit. Grant and his regiment were soon deployed to Missouri to confront Confederate forces.

On August 5, 1861, with Washburne’s assistance, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers. Major General John C. Frémont, the Union commander in the West, appointed Grant to lead the District of Southeastern Missouri. Grant arrived at Cairo, Illinois, on September 2, assumed command, and began planning a campaign along the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland Rivers.

As Confederate forces moved into western Kentucky, threatening southern Illinois, Grant took the initiative and captured Paducah, Kentucky, on September 6 without resistance. Recognizing the strategic importance of Kentucky’s neutrality, Grant assured local residents, “I have come among you not as your enemy, but as your friend.” Despite orders from Frémont to make only demonstrations against Confederate forces, Grant proceeded with his plans.

Belmont, Forts Henry and Donelson

On November 2, 1861, Lincoln removed Frémont from command, which allowed Grant to engage Confederate troops in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. On November 5, Grant and Brigadier General John A. McClernand landed 2,500 men at Hunter’s Point and fought the Confederates at the Battle of Belmont. Although the Union forces initially captured the camp, they were eventually forced to retreat due to a Confederate counterattack. Despite this, the battle boosted Ulysses S. Grant and his men’s confidence.

With Columbus, Kentucky, blocking Union access to the lower Mississippi, Grant and Lieutenant Colonel James B. McPherson devised a plan to bypass Columbus and target Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. After capturing Fort Henry with the help of Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote’s gunboats on February 6, 1862, Grant immediately moved against Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Unaware of the fort’s defenses, Grant and his officers initially faced setbacks but regrouped and ultimately overwhelmed the Confederate forces. On February 16, 1862, after a renewed assault and bombardment, Confederate generals John B. Floyd and Gideon J. Pillow fled, leaving Simon Bolivar Buckner to surrender the fort to Grant’s demand for “unconditional and immediate surrender.”

This victory was the first major Union triumph of the war, capturing over 12,000 Confederate troops. DespiteUlysses S. Grant success, his superior, Halleck, was displeased with Grant’s independent actions and accused him of neglect. Lincoln, however, promoted Grant to major general of volunteers, and the press, capitalizing on his initials, began referring to him as “Unconditional Surrender Ulysses S. Grant”

Shiloh (1862) and Aftermath

In the wake of his successful but costly victory at Fort Donelson, Ulysses S. Grant was reinstated by President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to lead the Army of the Tennessee. Grant’s primary objective was to advance into Tennessee. His main force was stationed at Pittsburg Landing, while 40,000 Confederate troops gathered at Corinth, Mississippi.

Ulysses S. Grant intended to attack the Confederates at Corinth but was ordered by Major General Henry Halleck to wait for Major General Don Carlos Buell and his 25,000-strong division. Instead of fortifying their position, Grant and his troops focused on drills, while reports of nearby Confederate forces were dismissed by his subordinate, William Tecumseh Sherman.

On April 6, 1862, Confederate forces under Generals Albert Sidney Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard launched a surprise attack on Grant’s troops near Shiloh Church. The Union forces, initially caught off guard, were driven back toward the Tennessee River. Johnston was killed in the battle, and command shifted to Beauregard. Despite heavy losses, Ulysses S. Grant managed to hold a line near Pittsburg Landing with the help of artillery and reinforcements, preventing a complete rout.

The next day, with additional troops from Major Generals Buell and Lew Wallace, Grant launched a counterattack at dawn, regaining control of the battlefield and forcing the Confederates to retreat to Corinth. Although Grant’s victory at Shiloh was significant, Halleck limited further pursuit. The battle, with its staggering 23,746 casualties, marked a turning point, leading Ulysses S. Grant to realize that complete conquest was necessary to save the Union.

Despite the victory, Grant faced criticism from the Northern press for the high number of casualties and allegations of drunkenness, although these claims were unsupported by eyewitness accounts. Lincoln defended Grant, stating, “I can’t spare this man; he fights.”

Vicksburg Campaign (1862–1863)

The capture of Vicksburg, the last major Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River, was crucial for the Union’s strategic control of the river. Initially, Lincoln appointed Major General John A. McClernand to lead the campaign against Vicksburg, but McClernand’s forces were eventually placed under Ulysses S. Grant command.

In November 1862, Ulysses S. Grant captured Holly Springs and advanced to Corinth, planning an overland attack on Vicksburg while Sherman would strike from Chickasaw Bayou. However, Confederate cavalry raids disrupted Union communications and recaptured Holly Springs, hindering the convergence of Grant’s and Sherman’s forces. McClernand conducted an independent campaign, capturing Fort Hindman, while Grant adapted by foraging and managing his supply lines.

Ulysses S. Grant pragmatic approach included setting up contraband camps and employing freed slaves in various capacities. However, his controversial General Order No. 11, which expelled Jews from his military district, was rescinded after protests from Lincoln and others.

In January 1863, Ulysses S. Grant assumed overall command of the campaign. To bypass Vicksburg’s defenses, he advanced his troops south through challenging terrain and ordered Admiral David Dixon Porter’s gunboats to run past the Confederate batteries. Grant’s diversionary tactics successfully moved his army across the Mississippi, capturing Jackson and defeating Pemberton’s forces at the Battle of Champion Hill.

Following intense assaults and a prolonged siege, Ulysses S. Grant forces captured Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. This victory gave the Union control of the Mississippi River, split the Confederacy, and bolstered Northern morale. Grant’s success in the West aligned him with the Radical Republicans’ agenda of aggressive war prosecution and emancipation.

Ulysses S. Grant achievements in the Vicksburg Campaign solidified his reputation, although he declined offers to move east to command the Army of the Potomac, preferring to remain in the West where he had greater familiarity with the geography and resources.

Chattanooga (1863) and Promotion

On October 16, 1863, President Lincoln promoted Ulysses S. Grant to major general in the regular army, assigning him command of the newly formed Division of the Mississippi, which included the Armies of the Ohio, the Tennessee, and the Cumberland. Following the Battle of Chickamauga, the Army of the Cumberland was besieged in Chattanooga.

Grant arrived in Chattanooga and quickly implemented a plan to resupply and break the siege. His forces, including Major General Joseph Hooker’s troops from the Army of the Potomac, linked up with units within the city. They captured Brown’s Ferry, opening a crucial supply line to the railroad at Bridgeport.

Grant’s strategy involved a combined assault on Missionary Ridge. On November 23, Major General George Henry Thomas achieved a significant victory by capturing Orchard Knob. Although Sherman failed to seize Missionary Ridge from the north, Hooker’s forces captured Lookout Mountain, marking a major success. On November 25, Grant ordered Thomas to advance to the rifle-pits at the base of Missionary Ridge. Despite Sherman’s failure to take the ridge from the northeast, Thomas’s troops, including divisions led by Major General Philip Sheridan and Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood, charged up the steep slope and captured the Confederate entrenchments along the crest, forcing a retreat. This decisive victory gave the Union control of Tennessee and opened Georgia to Union invasion.

Promotion to Lieutenant General

On March 2, 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general, making him the commander of all Union armies. Grant’s new rank had previously been held only by George Washington. He arrived in Washington on March 8 and was formally commissioned by Lincoln the following day. Grant developed a strong working relationship with Lincoln, who gave him the freedom to devise his own strategy.

Grant set up his headquarters with General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac in Culpeper, Virginia. He met weekly with Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Grant’s strategy involved five coordinated Union offensives to prevent Confederate armies from shifting troops. Grant and Meade would lead a direct assault on Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, while Sherman, now commanding all western armies, would destroy Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee and capture Atlanta. Major General Benjamin Butler would advance on Lee from the southeast up the James River, Major General Nathaniel Banks would capture Mobile, and Major General Franz Sigel would target the Shenandoah Valley. Grant commanded a total of 533,000 troops spread over an eighteen-mile front.

Overland Campaign (1864)

The Overland Campaign involved a series of brutal battles in Virginia during May and June 1864. Despite Sigel’s and Butler’s failures, Grant continued to engage Lee. On May 4, Grant led the army across the Rapidan River and launched an attack at the Battle of the Wilderness. The battle resulted in significant casualties: 17,666 Union and 11,125 Confederate.

Grant’s strategy involved flanking Lee’s army. After the Wilderness, he attempted to wedge his forces between Lee and Richmond at Spotsylvania Court House. This battle lasted thirteen days with heavy casualties. On May 12, Grant launched a bloody assault known as the Bloody Angle, but was unable to break through Lee’s lines. He then flanked Lee again, meeting at North Anna, where another costly battle occurred.

Cold Harbor

Grant’s plan to break through Lee’s lines at Cold Harbor, a crucial road hub, was marred by miscommunication and unexpected Confederate fortifications. Despite having a numerical advantage, Grant’s attack on June 3 resulted in heavy Union casualties: 12,000–14,000 compared to 3,000–5,000 for Lee. The battle caused heightened anti-war sentiment in the North. Grant later expressed regret over the assault, admitting it was a “stupendous failure.”

Siege of Petersburg (1864–1865)

Grant’s army moved south of the James River and laid siege to Petersburg, Virginia, a critical railroad hub. The siege lasted nine months, and Northern resentment grew. Grant directed Major General Philip Sheridan to “follow the enemy to their death” in the Shenandoah Valley. Despite an initial failure with the Union’s attack on Petersburg involving a disastrous assault after a mine explosion (known as the Battle of the Crater), Grant’s strategy to extend Lee’s defenses eventually succeeded.

Surrender of Lee and Union Victory (1865)

On April 2, 1865, Grant ordered a general assault on Lee’s forces. Lee abandoned Petersburg and Richmond, which Grant’s forces captured. Lee and part of his army attempted to join forces with Joseph E. Johnston’s remnants. Sheridan’s cavalry cut off their supply lines and blocked their escape route.

On April 9, Grant and Lee met at Appomattox Court House. Grant’s terms of surrender allowed Lee’s men to return home and keep their horses. Grant’s decision to avoid celebrating the victory underscored his desire for reconciliation: “the war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again.” Following Lee’s surrender, Johnston, Taylor, and Smith’s armies also surrendered, effectively ending the Civil War.

Lincoln’s Assassination

On April 14, 1865, Ulysses S. Grant attended a cabinet meeting in Washington, D.C. Lincoln had extended an invitation for Grant and his wife, Julia, to join him at Ford’s Theatre, but they declined as they had plans to return to their home in Burlington. In a dramatic plot aimed at destabilizing the Union, Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth at the theatre and died the following morning. There was speculation, including from Grant himself, that Booth’s conspirator, Michael O’Laughlen, might have had Grant in his sights as well.

During the ensuing trial, the government sought to prove that Grant had been targeted. Stanton informed Grant of Lincoln’s assassination and called him back to Washington. On April 15, Vice President Andrew Johnson was inaugurated as president. Grant was resolved to work alongside Johnson, expressing private optimism about Johnson’s ability to govern effectively.

Commanding Generalship (1865–1869)

As the Civil War came to a close, Grant remained in command of the Army, facing various challenges including dealing with French forces in Mexico, overseeing Reconstruction in the South, and managing conflicts with Native Americans on the western plains. After the Grand Review of the Armies, Lee and his generals faced treason charges in Virginia, but Grant argued against a trial, honoring the Appomattox amnesty. Grant secured a residence for his family in Georgetown Heights but maintained his legal residence in Galena, Illinois, for political reasons. On July 25, 1866, Congress elevated Grant to the newly established rank of General of the Army of the United States.

Tour of the South

President Johnson’s Reconstruction policy aimed for a swift reintegration of former Confederates into Congress, restoring white control in the South, while relegating African Americans to a lower status. On November 27, 1865, Johnson sent Grant on a fact-finding mission to the South to counteract a more negative report by Senator Carl Schurz, which highlighted Southern resentment and violence against African Americans. Grant recommended continuing the Freedmen’s Bureau, which Johnson opposed, and suggested against using black troops.

Grant believed the South was not yet ready for self-governance and needed federal protection to maintain order. His report on the South, which he later reconsidered, showed some alignment with Johnson’s policies. Although Grant supported the return of former Confederates to Congress, he also advocated for eventual black citizenship. On December 19, following the announcement of the Thirteenth Amendment’s passage in the Senate, Johnson used Grant’s report to counter Schurz’s findings and Radical opposition to his policies.

Break from Johnson

Initially, Grant was hopeful about Johnson. Despite their differing approaches, they had a cordial relationship, and Grant participated in Reconstruction-related cabinet meetings. However, by February 1866, their relationship soured. Johnson opposed Grant’s actions, such as shutting down the Richmond Examiner for disloyal editorials and enforcing the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Johnson’s “Swing Around the Circle” tour, aimed at garnering support for lenient Southern policies, was a failure, and Grant privately criticized it. On March 2, 1867, Congress passed the first of three Reconstruction Acts, using military officers to enforce policies. To protect Grant, Congress passed the Command of the Army Act, which restricted Johnson’s ability to bypass Grant.

In August 1867, Johnson fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton without Senate approval and appointed Grant as interim Secretary of War. Despite initial reservations, Grant accepted the position to ensure the Army remained under a progressive leadership. In December 1867, when Stanton was reinstated, Grant resigned to avoid legal complications, causing tension with Johnson. The fallout from this incident led to Johnson’s impeachment, though he was acquitted by one vote. Grant’s popularity surged among Radical Republicans, boosting his chances for the presidency.

Election of 1868

At the 1868 Republican National Convention, Grant was unanimously nominated for president, with Schuyler Colfax as vice president. Although Grant preferred military service, he accepted the nomination, believing he could unify the nation. The Republicans advocated civil rights and African American suffrage, while the Democrats, having abandoned Johnson, nominated Horatio Seymour and Francis P. Blair, opposing African American suffrage and seeking the restoration of former Confederate states with amnesty.

Grant took a passive role in the campaign, opting instead for a Western tour with Sherman and Sheridan. The Republicans adopted Grant’s slogan, “Let us have peace.” His controversial General Order No. 11 from 1862 was a campaign issue, but Grant emphasized his commitment to merit-based judgments. The Democrats and their Klan supporters focused on ending Reconstruction and intimidating voters. Grant won the popular vote and an Electoral College landslide, aided significantly by African American votes. At 46, he became the youngest elected president.

Presidency (1869–1877)

Grant was inaugurated as president on March 4, 1869, by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. He called for the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment and emphasized paying Civil War bonds in gold, as well as advocating for the “proper treatment” and eventual citizenship of Native Americans.

Grant’s cabinet choices were met with mixed reactions. Elihu B. Washburne, his initial Secretary of State, resigned, leading to Hamilton Fish’s appointment. Grant also faced difficulties with other appointments due to legal complications. His administration saw the establishment of Yellowstone National Park and a commitment to women’s rights. Grant made notable appointments of Jewish individuals to federal positions and supported anti-Semitic measures abroad. He proposed a constitutional amendment to limit religious instruction in public schools, which was incorporated into the Blaine Amendment but ultimately failed.

Grant also tackled polygamy and obscenity, prosecuting Mormon polygamists and pornographers under the Morrill and Comstock Acts, respectively.

Reconstruction

Grant was recognized for his efforts in civil rights, signing laws that promoted African American participation in juries and offices. The Reconstruction era saw Republican control in the South, supported by federal troops and congressional actions. Grant pushed for the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, leading to the full restoration of the Union and the first Black American legislators. His administration vigorously prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan, reducing their influence significantly by 1872.

However, during Grant’s second term, Northern support for Reconstruction waned as Southern conservative groups used violence and intimidation to regain power. Grant’s administration faced challenges including economic difficulties and scandals. Despite efforts to protect Republican governance in the South, by 1875, Redeemer Democrats had regained control in most Southern states. The Compromise of 1877 marked the end of Reconstruction, with federal troops withdrawn in exchange for Rutherford B. Hayes becoming president.

Financial Affairs

Grant sought to stabilize the economy by returning to pre-war monetary standards. He signed the Public Credit Act of 1869, which promised to repay bondholders in gold and committed to returning to the gold standard within a decade. Grant’s economic policies focused on “hard currency” and reducing the national debt, with guidance from business advisors.

Gold Corner Conspiracy (1869):

Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, two railroad tycoons, conspired to corner the gold market in New York to profit from high gold prices. They manipulated the market by gaining inside information and influencing President Grant’s decisions on gold sales. On September 24, 1869, known as Black Friday, Grant ordered a large sale of gold, causing the price to collapse and leading to a financial panic. Gould and Fisk fled, and the economic fallout lasted for months.

Foreign Affairs:

- Alabama Claims (1871): Grant’s administration settled disputes with Britain over damages caused by the Confederate ship CSS Alabama. The Treaty of Washington resolved these issues, with Britain admitting regret but not fault, and secured peace with Britain, making it a strong ally.

- Korean Expedition (1871): A U.S. naval and land force attempted to open trade with Korea and investigate the fate of the SS General Sherman. The mission failed to establish trade and instead reinforced Korea’s isolationist policies.

- Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic): Grant sought to annex the Dominican Republic to increase U.S. resources and naval protection. Despite initial support, the Senate, led by Senator Charles Sumner, rejected the annexation treaties, leading to Grant’s frustration and efforts to remove Sumner from his position.

- Cuba and Virginius Affair: In response to Spain’s execution of Americans aboard the Virginius, Grant ordered a show of force, but a diplomatic resolution was reached with Spain expressing regret and compensating the victims’ families.

- Free Trade with Hawaii (1875): Grant’s administration secured a free trade treaty with Hawaii, promoting U.S. economic interests and leading to increased American investment in Hawaiian sugar plantations.

Federal Indian Policy:

- Peace Policy: Grant aimed to assimilate Native Americans into European-American culture and governance. He appointed Ely S. Parker, a Native American, as Commissioner of Indian Affairs and signed legislation to oversee the policy and reduce corruption.

- Indian Wars: Despite Grant’s peaceful intentions, conflicts continued, including the Marias Massacre, the Modoc War, and the Great Sioux War. The policy of relocating Native Americans and the discovery of gold in the Black Hills led to further violence.

- Battle of Little Bighorn (1876): The Sioux, led by Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, defeated General Custer. Grant condemned Custer’s tactics and eventually persuaded the tribes to relinquish the Black Hills, though the policy and its impact on Native cultures were criticized.

Overall, Grant’s foreign and domestic policies reflected a mix of idealism, pragmatism, and the challenges of managing a diverse and evolving nation.

Election of 1872 and Grant’s Second Term

In the 1872 presidential election, the political landscape was marked by significant divisions. The Liberal Republicans, a faction dissatisfied with Grant’s leadership and his alliances with prominent politicians like Simon Cameron and Roscoe Conkling, distanced themselves from both Grant and the Republican Party. They criticized Grant for his perceived corruption and inefficiency and advocated for reforms such as withdrawing federal troops from the South, implementing literacy tests for Black voters, and granting amnesty to former Confederates.

The Liberals chose Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune and a staunch critic of Grant, as their presidential candidate, with Missouri Governor B. Gratz Brown as his running mate. Their platform condemned “Grantism” and sought significant changes. The Democratic Party also endorsed Greeley and Brown, aligning with the Liberal Republicans’ platform and pushing for a critique of the current administration.

The Republicans, on the other hand, nominated Grant for a second term with Senator Henry Wilson from Massachusetts as the vice presidential candidate. To counter the Liberal and Democratic criticisms, the Republicans adopted some of the Liberal platform’s ideas, such as extending amnesty, lowering tariffs, and pursuing civil service reform. Grant responded to these demands by lowering customs duties, providing amnesty to Confederates, and initiating civil service reforms, which helped to diminish opposition. The Republican platform also promised to give “respectful consideration” to women’s rights, a nod to the growing suffragist movement.

In terms of Southern policy, Grant supported federal protection for Black citizens, while Greeley favored local control by white populations. Grant’s campaign enjoyed support from prominent figures like Frederick Douglass and other reformers.

Grant’s reelection was decisive, secured by a strong economy, successful debt reduction, and his administration’s efforts against the Ku Klux Klan. He won 56% of the popular vote and an overwhelming Electoral College victory, with a final count of 286 to 66. Most African American voters in the South backed Grant, and despite some resistance in former slave states, his victory was seen as a personal vindication, though he felt let down by the Liberal Republicans.

Sworn in on March 4, 1873, by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, Grant’s second inaugural address focused on advancing freedom and fairness for all Americans, including the newly freed slaves. He concluded by expressing his commitment to fostering unity across the nation. Wilson’s death in office in November 1875 left Grant reliant on the advice of Treasury Secretary George W. Fish.

Panic of 1873 and the Loss of the House

The economic situation during Grant’s second term was troubled. The Coinage Act of 1873, which Grant signed, ended the use of silver dollars and established gold as the standard currency. This move, perceived by some as detrimental to farmers who needed more money in circulation, led to accusations of the “Crime of 1873” and sparked deflation.

Economic difficulties worsened with the Panic of 1873, triggered by the collapse of Jay Cooke & Company and its failure to sell Northern Pacific Railway bonds. Grant, lacking deep financial knowledge, consulted with New York businessmen to address the crisis. He ordered the Treasury to purchase government bonds, which helped to ease the panic, though the country entered a Long Depression, with significant railroad bankruptcies.

In 1874, Congress passed the Ferry Bill to combat the economic downturn by increasing the circulation of greenbacks. Although many supported this move, Grant vetoed the bill, fearing it would damage national credit. This decision aligned him with the conservative wing of the Republican Party and set a precedent for a gold-backed dollar. Grant later pushed for a bill to gradually reduce greenbacks in circulation, leading to the Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875, which aimed to return to a gold standard by 1879.

Reforms and Scandals

The post-Civil War era was characterized by industrial growth and government expansion, but it also saw rampant corruption. Grant’s administration faced numerous investigations due to the widespread corruption in federal offices. Despite Grant’s personal honesty, his approach to dealing with corruption was inconsistent, sometimes appointing reformers and at other times defending those implicated.

During Grant’s first term, he appointed Jacob D. Cox as Secretary of the Interior, who implemented civil service reforms, including firing unqualified clerks. However, Cox resigned over a dispute, and Grant later established the Civil Service Commission to enforce merit-based appointments and end political patronage.

In November 1871, Grant appointed Chester A. Arthur as the New York Collector, who continued reforms to improve customs practices. Investigations into corruption at the New York Customs House led to stricter regulations and prosecutions. Grant’s administration also tackled the notorious Whiskey Ring scandal, involving collusion between distillers and Treasury officials to evade taxes. Grant supported the crackdown on the ring, which resulted in significant fines and convictions.

Grant faced several scandals involving his administration, including the notorious Whiskey Ring and allegations against officials like Secretary of War William W. Belknap, who resigned after being implicated in kickback schemes. Despite these challenges, Grant attempted to address corruption by making cabinet changes and supporting reforms. In his December 5, 1876, Annual Message, Grant apologized for the failures, attributing them to errors in judgment rather than intent.