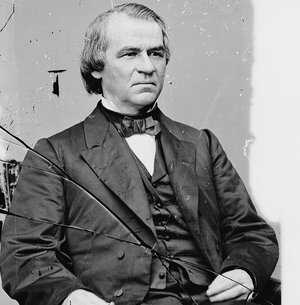

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808 – July 31, 1875) was a significant American political figure who served as the 17th President of the United States from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, having been Lincoln’s vice president at the time. As a Democrat, Johnson joined Lincoln on the National Union Party ticket, stepping into office as the Civil War came to an end.

Johnson advocated for the swift reintegration of the Southern states into the Union but did so without extending protections to the newly freed former slaves or taking a firm stance against former Confederates. This approach led to clashes with the Republican-controlled Congress and resulted in his impeachment by the House of Representatives in 1868. Johnson was acquitted in the Senate by just one vote.

Born into poverty and lacking formal education, Johnson began his working life as a tailor and lived in various frontier towns before establishing himself in Greeneville, Tennessee. There, he served as an alderman and mayor before being elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1835. Following a short stint in the Tennessee Senate, Johnson was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1843, where he served for ten years. He then became governor of Tennessee and was appointed to the Senate by the legislature in 1857.

During his time in Congress, he supported the Homestead Bill, which was passed shortly after he left his Senate seat in 1862. Although Southern states, including Tennessee, seceded to form the Confederate States of America, Johnson remained loyal to the Union, refusing to resign from his Senate seat. In 1862, Lincoln appointed him as Military Governor of Tennessee after much of the state was retaken. In 1864, Johnson was chosen as Lincoln’s running mate to reinforce a message of national unity and became vice president after their election victory.

Johnson’s presidency was marked by his implementation of Presidential Reconstruction, which involved issuing proclamations directing the Southern states to hold conventions and elections to rebuild their governments. Many Southern states reinstated former leaders and enacted Black Codes that limited the rights of freedmen. Congressional Republicans rejected these measures and pushed for legislation to counteract them, which Johnson vetoed. Congress overrode his vetoes, setting a pattern for the rest of his presidency.

Johnson opposed the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to former slaves, and in 1866, embarked on a national tour to promote his policies and challenge Republican opposition. As tensions between the executive and legislative branches intensified, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act to restrict Johnson’s ability to remove Cabinet officials. Johnson’s attempt to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin Stanton led to his impeachment by the House, though he narrowly escaped conviction in the Senate. He did not secure the 1868 Democratic presidential nomination and left office the following year.

After his presidency, Johnson returned to Tennessee and was eventually elected to the Senate in 1875, making him the only former president to serve in the Senate. He passed away just five months into his second term. Johnson’s staunch opposition to federal protections for Black Americans has been widely criticized, and historians often rank him among the least effective presidents in American history.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

- 13th President of the United States

- 14th President of the United States

- 15th President of the United States

- 16th President of the United States

- 17th President of the United States

- 18th President of the United States

- 19th President of the United States

Early Life and Career

Childhood

Andrew Johnson was born on December 29, 1808, in Raleigh, North Carolina, to Jacob Johnson (1778–1812) and Mary (“Polly”) McDonough (1783–1856), who worked as a laundress. His heritage was a mix of English, Scots-Irish, and Scottish descent. Johnson had an older brother, William, and a sister named Elizabeth who died young. His humble beginnings, growing up in a modest two-room shack, were a significant part of his political narrative, often highlighted during his campaigns.

Jacob Johnson, though originally poor, had managed to become the town constable of Raleigh before starting his family. He had previously worked as a porter for the State Bank of North Carolina, appointed by William Polk, a relative of President James K. Polk. Both Jacob and Mary Johnson were illiterate and had worked as tavern servants, while Andrew never attended formal school and grew up in poverty.

Jacob Johnson passed away from what seemed to be a heart attack while performing his duties as the town bellringer, shortly after rescuing three men from drowning, when Andrew was only three years old.

After Jacob’s death, Polly Johnson worked as a washerwoman, a job that was often looked down upon and required her to go into others’ homes unaccompanied. There were even rumors that Andrew might have been fathered by another man, as he did not resemble his siblings. Polly later remarried Turner Doughtry, who was as poor as she was.

Andrew Johnson’s mother apprenticed his older brother William to a tailor named James Selby, and at age ten, Andrew also began his apprenticeship in Selby’s shop. He was legally bound to serve until his 21st birthday. During his apprenticeship, Johnson lived with his mother, and one of Selby’s employees taught him basic literacy skills. His education was further supplemented by visitors who came to the shop to read aloud to the tailors, sparking a lifelong passion for learning. Annette Gordon-Reed, a biographer, suggests that Johnson’s public speaking skills may have been honed during his time as an apprentice.

Johnson was unhappy with his apprenticeship and, after about five years, he and his brother ran away. Selby offered a reward for their return: “Ten Dollars Reward. Ran away from the subscriber, two apprentice boys, legally bound, named William and Andrew Johnson … [payment] to any person who will deliver said apprentices to me in Raleigh, or I will give the above reward for Andrew Johnson alone.

” The brothers fled to Carthage, North Carolina, where Andrew worked as a tailor for several months. Fearing arrest, Johnson moved to Laurens, South Carolina, where he quickly found work and made a quilt for his first love, Mary Wood. However, she turned down his marriage proposal. Johnson returned to Raleigh, hoping to buy out his apprenticeship but was unable to settle terms with Selby. With no choice but to leave Raleigh to avoid being caught for his earlier escape, he decided to move west.

Move to Tennessee

Johnson left North Carolina for Tennessee, making most of the journey on foot. He spent a short time in Knoxville before relocating to Mooresville, Alabama. Eventually, he worked as a tailor in Columbia, Tennessee, but was soon called back to Raleigh by his mother and stepfather, who were looking for better prospects and planning to move west. Johnson’s party traveled through the Blue Ridge Mountains to Greeneville, Tennessee. Upon arrival, Johnson immediately fell in love with the town. He eventually purchased the land where he had first camped and planted a tree to commemorate his arrival.

In Greeneville, Johnson established a successful tailoring business out of his home. At 18, in 1827, he married 16-year-old Eliza McCardle, the daughter of a local shoemaker. Their marriage, officiated by Justice of the Peace Mordecai Lincoln, who was a cousin of President Abraham Lincoln’s father, lasted nearly 50 years and produced five children: Martha (1828), Charles (1830), Mary (1832), Robert (1834), and Andrew Jr. (1852). Eliza, despite suffering from tuberculosis, supported her husband’s career. She helped him with mathematics and improved his writing skills. Shy and reserved, Eliza usually stayed in Greeneville during Johnson’s political career and was rarely seen during his presidency; their daughter Martha often acted as the official hostess.

Johnson’s tailoring business thrived in his early years of marriage, allowing him to hire additional help and invest in real estate. He took pride in his tailoring skills, often boasting that his work never failed or came apart. Johnson was also an avid reader, particularly interested in books about famous orators, which fueled his interest in political debate. He engaged in discussions with customers holding different views and participated in debates at Greeneville College.

Andrew Johnson and His Slaves

In 1843, Andrew Johnson acquired his first slave, Dolly, who was 14 years old at the time. Dolly had three children: Liz, Florence, and William. Shortly after, Johnson also purchased Dolly’s half-brother, Sam, who, along with his wife Margaret, had nine children. Sam Johnson later became a commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau and was known for negotiating his work conditions with the Johnson family. Notably, he received some monetary compensation and was granted land by Andrew Johnson in 1867.

A 1928 biography described Sam Andrew Johnson as Andrew Johnson “favorite slave.” In 1857, Johnson bought Henry, a 13-year-old slave who later joined the Johnson family at the White House. By the end of his life, Johnson had owned at least ten slaves.

Andrew Johnson freed his slaves on August 8, 1863, but they continued to work for him as paid servants. A year later, as military governor of Tennessee, he declared the freedom of Tennessee’s slaves. Sam and Margaret lived in Johnson’s tailor shop during his presidency, without paying rent. In gratitude for his role in their emancipation, Johnson was presented with a watch inscribed “for his Untiring Energy in the Cause of Freedom” by newly freed people in Tennessee.

Political Rise and Career

Andrew Johnson began his political career in 1829 by helping organize a Mechanics’ ticket for the Greeneville municipal election, where he was elected town alderman. His prominence grew after advocating for a new state constitution and serving as Greeneville’s mayor in 1834. In 1835, he won a seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives and gained a reputation for his oratory skills and Democratic support.

Andrew Johnson political career continued with his election to the Tennessee Senate in 1841. He was a presidential elector in 1840 and later sold his tailoring business to focus on politics. Johnson’s influence extended to Congress, where he served from 1843 to 1853, advocating for the poor and opposing protective tariffs. His relationships with other political figures, including President James K. Polk, were often strained.

Despite setbacks, such as a defeat in 1837, Johnson’s political career flourished. He supported the Democratic Party and became known for his advocacy of the Homestead Bill and opposition to abolitionist policies. He won multiple elections and continued to influence national politics until the Whigs redrew his district boundaries, making his seat less secure.

Governor of Tennessee (1853–1857)

If Andrew Johnson had initially considered retiring from politics, he soon reconsidered. Political allies maneuvered to secure his gubernatorial nomination, which was unanimously granted at the Democratic convention, despite some discontent within the party. The Whigs, having dominated the last two gubernatorial elections and controlling the legislature, nominated Henry for the race. Johnson won the election narrowly, receiving 63,413 votes to Henry’s 61,163, with some votes influenced by Johnson’s promise to support Whig Nathaniel Taylor for Congress.

As governor, Andrew Johnson had limited power—he could propose but not veto legislation, and most appointments were controlled by the Whig legislature. Despite this, he used the office to promote his views and publicize his political stance. His notable achievements included reforms in the state judicial system, the abolition of the Bank of Tennessee, and establishing a uniform system of weights and measures. He also supported the creation of a public library, a public school system, and regular state fairs.

Facing a strong Whig opposition and a challenging political climate, Johnson won reelection in 1855. The campaign addressed issues like slavery, alcohol prohibition, and nativism. Johnson’s stance on these issues and his ability to connect with voters helped him secure a victory, though with a slimmer margin than before.

With the presidential election of 1856 approaching, Andrew Johnson, viewed as a potential compromise candidate, was ultimately overshadowed by James Buchanan. Johnson supported Buchanan but did not seek a third gubernatorial term, focusing instead on a U.S. Senate seat.

United States Senator

In 1857, with the Tennessee legislature’s control shifting to Democrats, Johnson was elected to the Senate. His rise to this position was marked by opposition from Whigs and Americans, who saw him as a significant threat. Despite this, Johnson was elected to the Senate due to his strong support among small farmers and tradesmen.

As a senator, Andrew Johnson championed the Homestead Bill, which aimed to grant land to settlers. However, Southern opposition and political complications, including the Dred Scott decision, hindered the bill’s progress. Johnson also opposed federal spending on infrastructure and military interventions, arguing against the expansion of federal power and military presence.

During the secession crisis, Andrew Johnson stance against the disunionist sentiment of the South made him a prominent Unionist voice. Despite threats and assaults on his life, he actively campaigned against secession in Tennessee. Although Tennessee eventually joined the Confederacy, Johnson remained loyal to the Union, fleeing the state and becoming a key figure in Lincoln’s administration.

Military Governor of Tennessee

In March 1862, Andrew Johnson was appointed military governor of Tennessee. He was confirmed along with the rank of brigadier general, and his appointment was part of Lincoln’s strategy to manage Union-held Southern regions. Johnson’s tenure saw efforts to suppress Confederate influence, enforce loyalty oaths, and shut down Confederate-sympathetic newspapers.

Under Andrew Johnson leadership, efforts to defend and recover parts of Tennessee from Confederate control continued, including the successful recruitment of African American soldiers into the Union Army. Johnson’s role was crucial in transitioning Tennessee from Confederate rule and in supporting the Union’s broader war efforts.

Vice Presidency (1865)

In 1864, Andrew Johnson was selected as Abraham Lincoln’s running mate for the presidential reelection campaign. Although Lincoln’s 1860 vice-presidential choice, Senator Hannibal Hamlin, was competent and willing to run again, Johnson was chosen for his role as a Southern War Democrat and his administration of Tennessee, which impressed Lincoln. Johnson’s selection was also influenced by a desire to present a unified front and demonstrate the feasibility of reconciliation with the South.

Andrew Johnson nomination was facilitated by political maneuvering and a desire to counteract the candidacy of Daniel S. Dickinson, a fellow War Democrat from New York. At the National Union Party convention in June 1864, Johnson was nominated for vice president on the second ballot, with strong support from delegates. Lincoln expressed satisfaction with Johnson’s selection.

Andrew Johnson campaign efforts were unusual for the time, as he actively spoke in several states and worked to disenfranchise voters who supported the Democratic candidate, George McClellan, by implementing a stricter loyalty oath. Despite this, Lincoln and Johnson won the election comfortably.

Andrew Johnson was eager to complete his work in Tennessee but was required to travel to Washington for his swearing-in. He faced challenges during his swearing-in on March 4, 1865, including illness and a hangover from excessive drinking at a pre-inauguration party. His performance was less than stellar, and he later retreated from public view, spending time away from Washington.

Presidency (1865–1869)

Andrew Johnson became President on April 15, 1865, following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was immediately thrust into a critical role at a pivotal moment in American history. He was sworn in by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase amidst the turmoil of Lincoln’s assassination. Johnson had a reputation for being a tough Unionist and made clear his intent to hold the South accountable.

He quickly asserted his authority by ensuring Lincoln’s policies were continued and dealing with ongoing Confederate issues. Andrew Johnson opposed a premature armistice agreement reached by General William T. Sherman and Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston and was critical of any concessions to the Confederacy. Johnson also offered a substantial reward for the capture of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and supported the execution of Mary Surratt, who was involved in Lincoln’s assassination plot.

Andrew Johnson presidency was marked by his efforts to navigate the complex Reconstruction era, dealing with the aftermath of the Civil War, and shaping the path for reintegrating the Southern states into the Union.

The Reconstruction Era: An Overview

When Andrew Johnson took office after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, he faced the complex issue of reintegrating the Southern states into the Union. Lincoln had proposed a relatively lenient plan, known as the “ten percent plan,” which would allow Southern states to rejoin the Union if 10% of their voters pledged loyalty. However, Congress rejected this plan as too lenient and proposed a stricter requirement for majority loyalty.

Johnson’s Goals:

- Rapid Reintegration: Andrew Johnson primary goal was to quickly restore the Southern states to the Union, believing they had never truly left. He thought that decisions about African American voting rights should be left to the states and not handled federally.

- Shift in Political Power: Andrew Johnson aimed to transfer political influence from the Southern planter elite to the common people, whom he favored. He was concerned that freed slaves might be influenced by their former masters.

- Election in 1868: Andrew Johnson aspired to win the presidency in 1868, something no one who had succeeded a deceased president had accomplished. He sought to build a Democratic coalition to oppose Congressional Reconstruction.

Republican Factions:

- Radical Republicans: These members sought full civil rights and voting rights for African Americans. They believed that African-American votes could secure Republican dominance and exclude former Confederates from power.

- Moderate Republicans: They wanted to keep former rebels from regaining power but were less enthusiastic about extending voting rights to African Americans.

- Northern Democrats: They supported the unconditional restoration of Southern states and opposed African-American suffrage, fearing it would undermine their control.

back to public life, where he may again become target of Nast’s work –

The Whirlgig of Time “Here we are again!” (Harper’s Weekly, February 20, 1875)

Presidential Reconstruction:

Initially, Andrew Johnson pursued a policy of quick restoration for Southern states without Congressional input. His approach led to the establishment of new Southern governments but did not address African-American suffrage or rights. The Southern states enacted Black Codes, which were restrictive laws targeting freed African Americans and led to growing Northern dissatisfaction.

Break with the Republicans:

By early 1866, Andrew Johnson policies had strained his relationship with both Radical and Moderate Republicans. His vetoes of crucial legislation, such as the Freedmen’s Bureau bill and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, as well as his opposition to the Fourteenth Amendment, deepened the divide. His public speeches, including the ill-fated “Swing Around the Circle” tour, further alienated him from Congress.

Radical Reconstruction:

After the 1866 elections, which saw a significant Republican victory, Congress passed laws placing Southern states under military control and required them to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment before rejoining the Union. Johnson’s vetoes of these laws were overridden. Radical Republicans pushed for comprehensive reforms, including military oversight and new state constitutions that allowed African Americans to vote and hold office.

Impeachment:

Andrew Johnson removal of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a holdover from Lincoln’s administration, triggered his impeachment. He was accused of violating the Tenure of Office Act, which restricted the president’s ability to remove cabinet members without Senate approval. The Senate trial ended with Johnson narrowly escaping removal from office. The final vote fell just one vote short of the required two-thirds majority for conviction.

Conclusion:

Andrew Johnson presidency was marked by significant conflict with Congress over how to handle Reconstruction. His inability to effectively manage these relationships and his controversial actions led to his impeachment, although he remained in office until his term ended. The Reconstruction Era continued to develop as the nation worked to integrate the Southern states and address the rights of freed slaves.

Foreign Policy During Johnson’s Presidency

Upon becoming President, Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William H. Seward agreed to maintain the existing foreign policy direction. This meant Seward would continue managing foreign affairs as he had under Lincoln. Although Seward and Lincoln were rivals for the 1860 nomination, Seward was expected to be Lincoln’s successor in 1869. At the time, the French had deployed troops to Mexico, causing some American politicians to advocate for a more aggressive stance. However, Seward preferred diplomatic measures and cautioned the French that their presence in Mexico was unacceptable.

Despite Johnson’s preference for a tougher approach, Seward convinced him to adopt a more measured response. In April 1866, the French government announced plans to withdraw its troops by November 1867. On August 14, 1866, Johnson and his cabinet hosted Queen Emma of Hawaii, who was returning to her home after travels in Britain and Europe.

Seward, an expansionist, sought to acquire new territories for the United States. After the Crimean War in the 1850s, Russia viewed its North American colony, now Alaska, as a financial burden and feared British annexation. Negotiations to purchase Alaska were stalled by the Civil War but resumed afterward. Russian Minister Baron Eduard de Stoeckl negotiated the sale with Seward, who increased his initial offer from $5 million to $7 million, plus an additional $200,000 due to various objections.

This amount, equivalent to $157 million today, was agreed upon on March 30, 1867. The Senate approved the treaty on April 1, just before adjournment. Seward’s success with Alaska led him to seek other acquisitions, but his attempts to acquire the Danish West Indies failed when the Senate did not vote on the treaty, causing it to expire.

Another setback was the Johnson-Clarendon Convention, which aimed to address the Alabama Claims—damages from British-built Confederate raiders on American shipping. Negotiated by U.S. Minister Reverdy Johnson in late 1868, the treaty was ignored by the Senate and rejected after Johnson left office. The Grant administration later secured more favorable terms from Britain.

Andrew Johnson Administration and Cabinet

President: Andrew Johnson (1865–1869)

Vice President: None (1865–1869)

Secretary of State: William H. Seward (1865–1869)

Secretary of the Treasury: Hugh McCulloch (1865–1869)

Secretary of War: Edwin Stanton (1865–1868), John Schofield (1868–1869)

Attorney General: James Speed (1865–1866), Henry Stanbery (1866–1868), William M. Evarts (1868–1869)

Postmaster General: William Dennison Jr. (1865–1866), Alexander Randall (1866–1869)

Secretary of the Navy: Gideon Welles (1865–1869)

Secretary of the Interior: John Palmer Usher (1865), James Harlan (1865–1866), Orville Hickman Browning (1866–1869)

Judicial Appointments

During his presidency, Andrew Johnson appointed nine federal judges to the district courts but did not appoint anyone to the Supreme Court. He nominated Henry Stanbery in April 1866 to fill a vacancy, but Congress eliminated the seat to block his appointment. Johnson appointed Samuel Milligan to the U.S. Court of Claims in 1868, where Milligan served until his death in 1874.

Reforms

In June 1866, Johnson signed the Southern Homestead Act, aiming to help poor whites, but the law mostly benefited a few and was marred by fraud. In June 1868, he signed an eight-hour workday law for federal laborers, though the intent was undermined by wage cuts.

End of Term and Legacy

Andrew Johnson sought the Democratic nomination in July 1868 but was only a strong contender in the South. He was ultimately outpaced by Horatio Seymour. Despite proposing amendments to limit presidential terms and reform judicial appointments, Congress took no action. Johnson was required to report the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment by Southern legislatures in July 1868.

In his final months, Johnson issued a general amnesty and pardons, including one for Dr. Samuel Mudd, convicted for his role in the Lincoln assassination. On his last day in office, Johnson hosted a public reception but did not attend Grant’s inauguration. He returned to Greeneville, Tennessee, where he encountered personal and political challenges. Johnson’s bid for Senate in 1875 succeeded after a contentious election, making him the only former president to serve in the Senate. He served briefly before dying from a stroke in July 1875.

Historical Reputation

Andrew Johnson presidency has been the subject of varied historical interpretations. Early assessments often criticized him for his handling of Reconstruction. James Ford Rhodes viewed Johnson as obstinate, attributing many of his failings to personal weaknesses. Later historians, including the Dunning School, rehabilitated Johnson’s image, viewing his policies as fundamentally correct despite his political flaws. In the 1920s, Johnson was increasingly portrayed as a martyr for his battle against radical Republicans. However, modern assessments often list him among the worst presidents due to his mishandling of Reconstruction and resistance to civil rights advancements.