Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804 – October 8, 1869) was an American statesman who served as the 14th President of the United States from 1853 to 1857. As a northern Democrat, he viewed the abolitionist movement as a grave danger to the nation’s unity, which led him to alienate anti-slavery factions by endorsing the Kansas–Nebraska Act and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act. The tension between the North and South persisted after Pierce’s term, culminating in the secession of Southern states following Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, which ignited the American Civil War.

Pierce was born in New Hampshire, the son of Benjamin Pierce, a state governor. He began his political career in the House of Representatives from 1833 to 1837 before moving to the Senate, where he served until resigning in 1842. After a successful private law practice, he was appointed U.S. Attorney for New Hampshire in 1845. During the Mexican American War, Pierce served as a brigadier general.

The Democratic Party saw him as a unifying figure for Northern and Southern interests and nominated him for the presidency on the 49th ballot at the 1852 Democratic National Convention. He and his running mate, William R. King, decisively defeated the Whig candidates Winfield Scott and William A. Graham in the 1852 election.

During his presidency, Pierce sought to maintain a balanced approach to civil service appointments while satisfying the diverse factions within the Democratic Party. His efforts largely failed, leading to dissatisfaction within his party. An advocate of the Young America movement, Pierce signed the Gadsden Purchase, expanding U.S. territory, and attempted unsuccessfully to acquire Cuba.

He also signed trade agreements with Britain and Japan. However, his administration was overshadowed by political turmoil, especially after he supported the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and led to violent conflicts over slavery in the West. His administration further suffered when the Ostend Manifesto, advocating for the annexation of Cuba, was widely condemned. Although Pierce expected to be renominated in the 1856 election, the Democrats chose another candidate, leaving him without a second term.

Pierce was personable and sociable, but his personal life was marked by tragedy; his three children died young, and his wife, Jane Pierce, struggled with illness and depression. Their last surviving son died in a train accident just before Pierce’s inauguration. A long-time heavy drinker, Pierce passed away in 1869 from cirrhosis. Due to his pro-Southern stance and inability to prevent the Union’s disintegration, historians and scholars often rank him among the least effective and memorable U.S. Presidents.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

- 13th President of the United States

- 14th President of the United States

Early Life and Family Background

The Franklin Pierce Homestead, located in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, where Pierce spent his formative years, has been designated a National Historic Landmark. Pierce was born on November 23, 1804, in a nearby log cabin while the homestead was being constructed.

Childhood and Education

Franklin Pierce was born in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, and was a sixth-generation descendant of Thomas Pierce, who emigrated from Norwich, Norfolk, England, to the Massachusetts Bay Colony around 1634. His father, Benjamin Pierce, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, settled in Hillsborough after the conflict, purchasing 50 acres of land. Franklin was the fifth of eight children born to Benjamin and his second wife, Anna Kendrick. Benjamin’s first wife, Elizabeth Andrews, had died in childbirth, leaving behind a daughter. A prominent Democratic-Republican state legislator, farmer, and tavern keeper, Benjamin Pierce was actively involved in state politics. Franklin’s early life was influenced by his father’s political career and his older brothers’ service in the War of 1812.

Franklin Pierce father enrolled him in a local school at Hillsborough Center during his early years and later sent him to the town school in Hancock at the age of 12. Franklin, who was not particularly fond of schooling, became homesick and once walked 12 miles back home on a Sunday. His father gave him dinner and then drove him partway back to school, forcing him to walk the rest of the distance in a thunderstorm—a moment Franklin later described as a pivotal point in his life. That same year, he transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy to prepare for college. Known for his charming personality, Franklin Pierce occasionally got into trouble but worked hard to improve his academic standing.

Friendships and Academic Life

In the fall of 1820, Franklin Pierce enrolled at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, as one of 19 freshmen. He joined the Athenian Society, a progressive literary group, where he forged lasting friendships with future Congressman Jonathan Cilley and novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne. Initially ranking last in his class, he improved significantly and graduated fifth out of 14 in 1824. During his junior year, Pierce organized an unofficial militia unit called the Bowdoin Cadets, which included Cilley and Hawthorne. The cadets’ drilling near the college president’s house led to a student strike when they were ordered to stop. In his final year, Pierce taught at Hebron Academy in Maine, earning his first salary and teaching future Congressman John J. Perry.

Legal and Political Beginnings

Franklin Pierce briefly studied law under former New Hampshire Governor Levi Woodbury, a family friend, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He later attended Northampton Law School in Massachusetts and continued his studies with Judge Edmund Parker in Amherst, New Hampshire. Admitted to the New Hampshire bar in late 1827, Pierce began practicing law in Hillsborough. Though his first case was unsuccessful, his charm and excellent memory for names and faces soon made him a capable lawyer. In Hillsborough, he partnered with Albert Baker, brother of Mary Baker Eddy.

By 1824, New Hampshire was politically divided, with emerging Democrats, including figures like Woodbury and Isaac Hill, supporting General Andrew Jackson and opposing the Federalists and their successors, the National Republicans, led by President John Quincy Adams. The Democratic Party’s efforts paid off when Benjamin Pierce won the 1827 gubernatorial election with the support of the pro-Adams faction. Franklin Pierce, initially focused on his legal career, became increasingly involved in politics as the 1828 presidential election approached. Despite the Adams faction’s withdrawal of support, which led to his father’s loss in the 1828 gubernatorial race, Franklin was elected Hillsborough’s town meeting moderator, a position he held for five terms.

Military Involvement and Rise in Politics

Franklin Pierce actively campaigned for Jackson in the 1828 presidential election, and Jackson’s victory bolstered the Democratic Party in New Hampshire. Pierce was elected to the New Hampshire House of Representatives in 1829, where he served as chairman of the House Education Committee and later the Committee on Towns. By 1831, he was elected Speaker of the House, where he opposed the expansion of banking, supported the state militia, and aligned with national Democrats. At 27, he was a rising star in New Hampshire politics. Despite his success, Pierce lamented his bachelorhood in personal letters and longed for a life beyond Hillsborough.

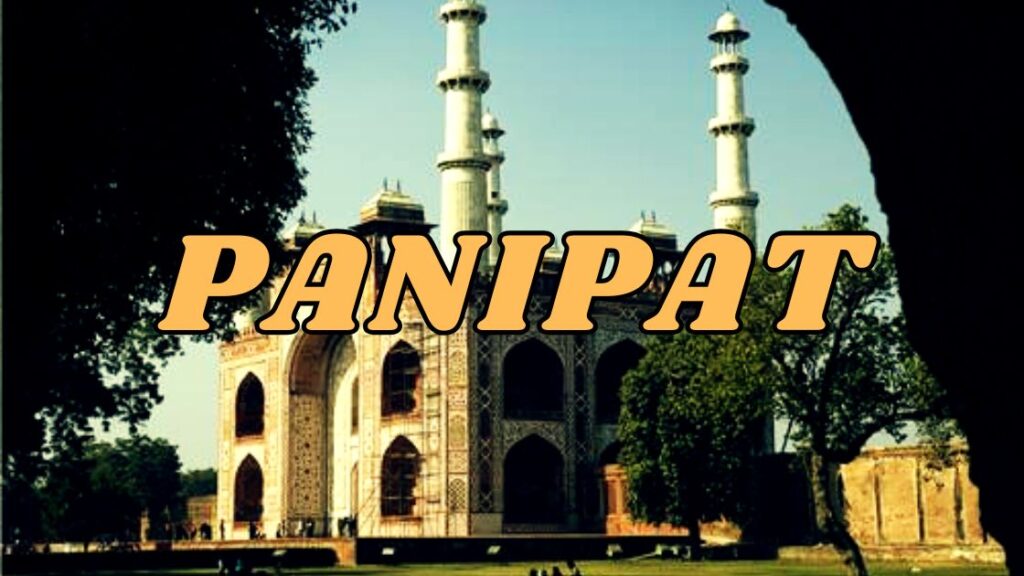

Franklin Pierce served in the state militia and was appointed aide de camp to Governor Samuel Dinsmoor in 1831. He rose to the rank of colonel and later brigadier general during the Mexican American War. Passionate about revitalizing the state militias, Pierce worked with military college leaders to improve recruitment and training. He was a trustee of Norwich University and received an honorary LL.D. degree from the institution in 1853.

Marriage and Family

On November 19, 1834, Franklin Pierce married Jane Means Appleton, daughter of Congregational minister Jesse Appleton and Elizabeth Means. The Appletons were prominent Whigs, contrasting with the Pierce family’s Democratic leanings. Jane was shy, deeply religious, and pro-temperance, encouraging Pierce to abstain from alcohol. Despite her disdain for politics and Washington, DC, the couple moved to Concord, New Hampshire, in 1838. They had three sons, all of whom died young: Franklin Jr. died in infancy, Frank Robert died at four from epidemic typhus, and Benjamin died at 11 in a train accident.

Congressional Career

U.S. House of Representatives

Franklin Pierce embarked on his congressional career in November 1833, when he traveled to Washington, D.C., to participate in the Twenty-third United States Congress, which began its regular session on December 2. At the time, President Andrew Jackson was serving his second term, and the House of Representatives had a strong Democratic majority. The primary focus of this majority was to prevent the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States. Franklin Pierce, aligned with the Democrats, played a role in defeating the Whig Party-supported proposals to recharter the bank, allowing its charter to expire.

Despite his alignment with the Democratic Party, Pierce occasionally broke ranks, particularly on issues related to federal funding for internal improvements, which he considered unconstitutional and believed should be the responsibility of individual states. His first term in Congress was relatively uneventful, and he was easily re-elected in March 1835. During his time away from Washington, Pierce continued practicing law, returning to the capital in December 1835 for the Twenty-fourth Congress.

As abolitionism became more prominent in the mid-1830s, Congress received numerous petitions from anti-slavery groups advocating for legislation to restrict slavery in the United States. Franklin Pierce found the abolitionists’ fervor annoying and believed that federal action against slavery infringed on the rights of Southern states, despite his personal moral opposition to the institution. He expressed his views on slavery, stating, “I consider slavery a social and political evil and most sincerely wish that it had no existence upon the face of the earth.” However, he also believed that the abolition movement needed to be subdued to maintain the Union.

When Representative James Henry Hammond of South Carolina sought to prevent anti-slavery petitions from reaching the House floor, Pierce sided with the abolitionists’ right to petition. Nonetheless, he supported the “gag rule,” which allowed petitions to be received but not read or considered. This rule was passed by the House in 1836. Pierce faced criticism from the New Hampshire anti-slavery Herald of Freedom, which labeled him a “doughface,” implying a Northern sympathizer with Southern interests. Pierce responded by clarifying that most signatories of the petitions were women and children, who could not vote, challenging the Herald of Freedom’s portrayal of New Hampshire as a hotbed of abolitionism.

U.S. Senate

Franklin Pierce Senate career began in December 1836 when he was elected to a full term commencing in March 1837, following the resignation of Senator Isaac Hill. At the age of 32, Franklin Pierce was one of the youngest members in Senate history at that time. His election came during a challenging period, with his father, sister, and brother seriously ill, and his wife suffering from chronic poor health.

As a senator, Franklin Pierce generally followed the Democratic Party line on most issues but did not stand out as an eminent figure, overshadowed by prominent senators like John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster. He entered the Senate during the economic turmoil of the Panic of 1837, which he attributed to the banking system’s rapid growth and speculative practices. Pierce supported President Martin Van Buren’s proposal to create an independent treasury, believing it would prevent federal money from supporting speculative bank loans. This proposal divided the Democratic Party.

The debate over slavery continued in Congress, with proposals to abolish it in the District of Columbia. Franklin Pierce supported a resolution by Calhoun opposing these proposals, viewing them as potential precursors to nationwide emancipation. As the Whigs gained strength in Congress, Pierce’s party found itself with only a small majority by the end of the decade.

Franklin Pierce took a particular interest in military affairs, advocating for the modernization and expansion of the Army, focusing on militias and mobility. He served as chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Pensions during the Twenty-sixth Congress (1839–1841) and worked to address fraud within the military pension system.

Franklin Pierce campaigned vigorously for Van Buren’s re-election in the 1840 presidential election. Although Van Buren carried New Hampshire, he lost to Whig candidate William Henry Harrison. The Whigs then gained a majority in the Twenty-seventh Congress. Harrison’s death after a month in office led to Vice President John Tyler’s succession, which prompted Pierce and the Democrats to challenge the new administration on various issues, including the removal of federal officeholders and Whig plans for a national bank.

In December 1841, Franklin Pierce decided to resign from Congress, a decision influenced by his frustration with being in the legislative minority and his desire to focus on his family and law practice. He made his last actions in the Senate in February 1842, opposing a bill to distribute federal funds to the states, believing the funds should be allocated to the military instead. He also challenged the Whigs to disclose the findings of their investigation into the New York Customs House, where they had been probing for Democratic corruption for nearly a year without issuing any results.

Franklin Pierce: A Journey Through Politics and Service

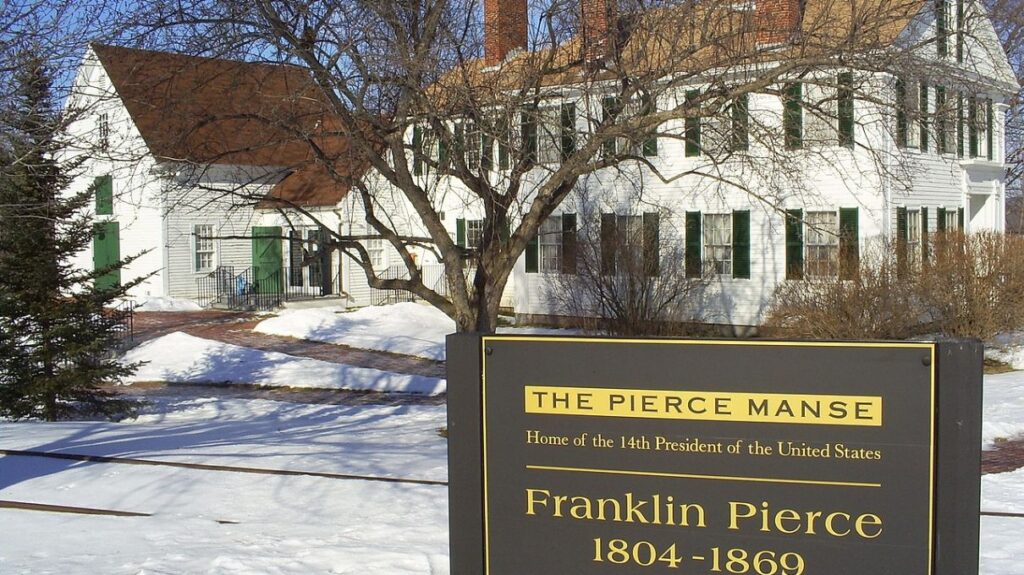

Franklin Pierce, a dedicated party leader, lawyer, and politician, lived in a historic white house in Concord, New Hampshire, from 1842 to 1848. Known today as the Pierce Manse, this house was restored in the 1970s and is preserved as a historical landmark. Despite resigning from the Senate, Pierce continued to be active in public life. The move to Concord allowed him more opportunities for legal work and provided his wife, Jane Pierce, with a supportive community.

During his Senate term, Jane stayed in Concord with their sons, Franklin Pierce and Benjamin. This separation strained the family, but Pierce’s burgeoning law practice, partnered with Asa Fowler, proved both demanding and lucrative. Pierce was renowned for his gracious demeanor, eloquence, and sharp memory, often attracting large audiences in court. He frequently represented the poor, sometimes without compensation.

Pierce remained deeply involved in the state Democratic Party, which was divided over issues like government support for corporations and social programs. Governor Isaac Hill, representing the urban wing, supported government charters for corporations, while the radical “Locofoco” wing advocated for the interests of farmers and rural voters. After the Panic of 1837, New Hampshire’s political climate grew hostile toward banks and corporations, leading to Hill’s ousting. Pierce, aligning more with the radicals, reluctantly represented Hill’s adversary in a legal dispute, resulting in Hill losing the case and targeting Pierce in his newly founded newspaper.

In 1842, Pierce was appointed chairman of the State Democratic Committee. He played a pivotal role in helping the radical wing gain control of the state legislature. He prioritized “order, moderation, compromise, and party unity,” even when it meant setting aside his own political views. Pierce’s strong support for the Democratic Party’s unity often led him to oppose anti-slavery movements, which he saw as divisive.

Pierce campaigned vigorously for James K. Polk in the 1844 presidential election, and Polk appointed him as United States Attorney for New Hampshire. However, the annexation of Texas, a significant issue during Polk’s presidency, created a rift between Pierce and his former ally, John P. Hale. Hale’s staunch opposition to adding another slave state led to a public split, with Pierce working to revoke Hale’s nomination for Congress. This political battle caused a deep divide in the New Hampshire Democratic Party, ultimately leading to Hale’s election to the Senate, much to Pierce’s dismay.

Mexican American War and Military Service

A long-held dream of military service came true for Pierce during the Mexican–American War. Despite his family’s history of military service, his own experience as a militia officer was limited. When war broke out in 1846, Pierce quickly volunteered, eventually becoming a brigadier general. He led his brigade in several key battles, including the Battle of Contreras, where he sustained a debilitating knee injury. Despite his injury, Pierce continued to lead his troops, demonstrating resilience and commitment. Although his military service was brief, it boosted his public image, despite accusations of cowardice due to his injuries and illnesses during the campaign.

Ulysses S. Grant, who observed Pierce during the war, later defended him against these accusations, stating that Pierce was a gentleman and courageous, despite any political differences.

Return to New Hampshire and Political Ascendancy

Upon returning to Concord, Pierce resumed his law practice and continued to be a prominent figure in the New Hampshire Democratic Party. He defended the religious liberty of the Shakers and engaged in various legal battles. However, his political involvement overshadowed his legal career. Pierce supported the Compromise of 1850, a series of measures designed to address the issue of slavery in new territories, and worked to maintain party unity.

Pierce’s support for the Democratic Party was unwavering, even when the party was divided over the issue of slavery. He declined an offer from the Free Soil Party to run as vice president and instead supported Lewis Cass. Pierce’s efforts helped to hold New Hampshire to a low vote percentage for Zachary Taylor, who eventually won the presidency.

The Compromise of 1850 and the subsequent political landscape set the stage for Pierce’s candidacy in the 1852 presidential election. Despite being out of office for a decade, Pierce emerged as a dark horse candidate at the Democratic National Convention. He won the nomination on the 49th ballot after securing broad support from southern delegates. His running mate, Alabama Senator William R. King, was chosen to balance the ticket.

The 1852 election was marked by a lack of clear political differences between the Democrats and Whigs. Pierce’s campaign was characterized by his absence from public campaigning, in line with the custom of the time. He faced harsh attacks from his opponents, who labeled him as an anti-Catholic and an alcoholic. However, his party’s unity and support for the Compromise of 1850 helped him secure a decisive victory.

Pierce won the election with a significant electoral margin, becoming the 14th President of the United States. His victory was a triumph for the Democratic Party, which gained a strong majority in Congress. Despite the accusations and challenges he faced, Pierce’s political career and leadership within his party left a lasting impact on American history.

Presidency (1853–1857)

Transition and Train Accident

Pierce’s presidency began under the shadow of personal tragedy. On January 6, 1853, weeks after his election, Pierce and his family were involved in a train accident near Andover, Massachusetts, when their car derailed and tumbled down an embankment. Although Franklin and Jane Pierce survived, their only surviving son, 11-year-old Benjamin, tragically died in the accident. The young boy was crushed in the wreckage, and the sight was so gruesome that Pierce could not shield his wife from it.

This heartbreaking event left the Pierces in deep depression, significantly impacting Pierce’s time in office. Jane Pierce even questioned if the accident was divine retribution for her husband’s political ambitions, penning a sorrowful letter to “Benny” apologizing for her perceived shortcomings as a mother. She withdrew from public life for much of Pierce’s first two years in office, only making her debut as First Lady at the White House reception on New Year’s Day, 1855.

When it was time for Pierce to leave New Hampshire for the inauguration, Jane chose not to join him. Pierce, the youngest president-elect at the time, took his oath of office on a law book, deviating from the tradition of using a Bible. He delivered his inaugural address from memory, emphasizing a time of peace and prosperity and advocating for a strong assertion of U.S. interests, including the acquisition of new territories. Without mentioning slavery, he expressed a desire to resolve the issue peacefully. Pierce acknowledged his personal grief in his address, saying, “You have summoned me in my weakness; you must sustain me by your strength.

Administration and Political Tensions

In forming his Cabinet, Pierce aimed to balance the various factions within the Democratic Party, which were divided over the Compromise of 1850 and other issues. This effort led to internal party conflicts, with Northern newspapers accusing Pierce of favoring pro-slavery secessionists and Southern newspapers accusing him of abolitionism. The appointment of Cabinet members and the distribution of lower-level federal positions became a contentious process, causing frustration and tension within the party.

The sudden death of Vice President William R. King shortly after the inauguration left the position vacant for the remainder of Pierce’s term. This vacancy meant that the Senate President pro tempore, initially David Atchison, was next in line for the presidency.

Pierce’s administration sought to improve government efficiency and accountability. His Cabinet implemented an early civil service examination system and made significant reforms in various departments, including the Treasury and the Interior. Pierce also appointed John Archibald Campbell to the Supreme Court, advocating states’ rights.

Economic Policy and Internal Improvements

Treasury Secretary James Guthrie worked to reform the Treasury, addressing inefficiencies and prosecuting corrupt officials. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis conducted surveys for a possible transcontinental railroad and oversaw significant construction projects in Washington, D.C. Pierce supported a southern route for the railroad, justified as a national security objective.

Foreign and Military Affairs

The Pierce administration, aligned with the expansionist Young America movement, pursued a distinctively American image in foreign relations. Secretary of State William L. Marcy advocated for American diplomats to dress simply and employ American citizens in consulates. The administration successfully defended Austrian refugee Martin Koszta and negotiated the Gadsden Purchase, acquiring land for a potential railroad. However, Pierce faced challenges in foreign relations, particularly with Britain and Spain, including the controversial Ostend Manifesto, which proposed the acquisition of Cuba.

| Office | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| President | Franklin Pierce | 1853–1857 |

| Vice President | William R. King | 1853 |

| None | 1853–1857 | |

| Secretary of State | William L. Marcy | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | James Guthrie | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of War | Jefferson Davis | 1853–1857 |

| Attorney General | Caleb Cushing | 1853–1857 |

| Postmaster General | James Campbell | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Navy | James C. Dobbin | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Robert McClelland | 1853–1857 |

Bleeding Kansas

The Kansas–Nebraska Act, a significant and contentious piece of legislation during Pierce’s presidency, proposed organizing the Nebraska Territory and allowing local settlers to decide on slavery. The act effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise, leading to a fierce political battle. The resulting violence in Kansas, known as “Bleeding Kansas,” saw pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers clash, further inflaming sectional tensions.

The midterm elections of 1854 and 1855 were disastrous for the Democrats, with significant losses in the North. The Know-Nothings and the newly formed Republican Party gained ground, reflecting growing opposition to Pierce’s policies, particularly his handling of the Kansas–Nebraska Act and enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Pierce’s presidency was marked by internal and external challenges, political strife, and a tragic personal life. His administration’s efforts to manage these issues were met with mixed success, leaving a complex legacy.

1856 Election and Its Aftermath: A Fresh Perspective

Prelude to the Election

The 1856 presidential election was a turbulent time in American politics, marked by intense sectional conflict and political realignment. The violence of “Bleeding Kansas” spilled into Congress in May 1856, when Free Soil Senator Charles Sumner was brutally attacked by Democratic Rep. Preston Brooks with a cane in the Senate chamber, symbolizing the nation’s growing divide.

President Franklin Pierce, despite his administration’s controversial stance on the Kansas–Nebraska Act, hoped for renomination by the Democratic Party. However, his chances were slim, as many Democrats viewed him as an electoral liability. James Buchanan, who had been serving as Minister to the United Kingdom, emerged as a strong candidate, untainted by domestic controversies. Pierce’s supporters sought to ally with Stephen A. Douglas to block Buchanan’s nomination.

The Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention convened in Cincinnati, Ohio, on June 5, 1856. Pierce anticipated a strong showing, but the first ballot revealed his weakening support, with Buchanan leading and Douglas and Lewis Cass also in contention. As the balloting progressed, Pierce’s chances dwindled. In a strategic move, Pierce instructed his supporters to back Douglas, hoping to prevent a Buchanan victory. Douglas, however, decided to defer his ambitions, trusting he could win the presidency in the future, and thus Buchanan secured the nomination. The convention attempted to soften Pierce’s defeat by passing a resolution of “unqualified approbation” of his administration and nominating John C. Breckinridge as Buchanan’s running mate.

This outcome was unprecedented, as it was the first time in U.S. history that an incumbent president seeking re-election was not nominated by his party.

Campaign and Election Outcome

Pierce endorsed Buchanan, albeit with reservations, and focused on resolving the Kansas crisis before the general election. He appointed John W. Geary as territorial governor, who faced resistance from pro-slavery factions but eventually restored order. Despite these efforts, the Democrats suffered in the North, where “Bleeding Kansas” and “Bleeding Sumner” became rallying cries for the Republican opposition. The Buchanan/Breckinridge ticket won the election, but the Democratic vote share in the North dropped significantly.

In his final message to Congress in December 1856, Pierce attacked Republicans and abolitionists, defending his policies and lamenting the state of the nation. He concluded his presidency with a reduction in tariffs, an increase in military pay, and the construction of new naval vessels. Notably, Pierce’s cabinet remained intact throughout his term, an uncommon occurrence.

Post-Presidency and Later Years

After leaving office, Pierce and his wife Jane resided briefly with former Secretary of State William L. Marcy before moving to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Pierce remained politically active, criticizing the growing sectional tensions and opposing the idea of northern abolitionists inciting southern secession. He maintained a close friendship with Jefferson Davis, who would later become President of the Confederate States of America.

Pierce declined calls to run as a compromise candidate in the 1860 election, supporting Breckinridge instead. As the Civil War loomed, Pierce advocated for peaceful resolution and criticized Lincoln’s wartime policies, including the suspension of habeas corpus. He faced backlash from northern newspapers and public opinion, especially after his friendship with Davis became widely known.

Final Years and Legacy

Jane Pierce’s death in 1863 deeply affected Pierce, as did the loss of his close friend Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1864. He distanced himself from public life, focusing on his personal affairs and supporting Davis during his imprisonment. Pierce’s health declined due to alcoholism, leading to his death on October 8, 1869. President Ulysses S. Grant declared a day of national mourning, and Pierce was buried next to his wife and sons in Concord, New Hampshire.

Memorials and Honors

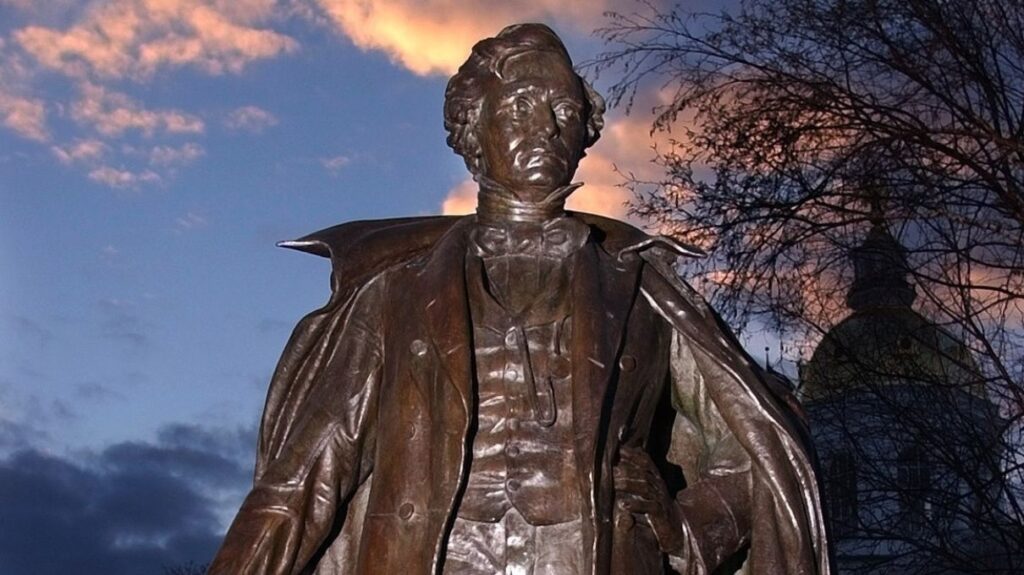

Franklin Pierce’s legacy is preserved in several ways. His homestead in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, is a state park and National Historic Landmark. A statue of Pierce stands at the New Hampshire State House, and various historical markers across the state commemorate his life. Educational institutions like Franklin Pierce University and the Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property at the University of New Hampshire School of Law bear his name. Additionally, places such as Pierce County, Washington, and Pierce County, Georgia, honor him. Despite his controversial presidency, Pierce’s impact on American history continues to be remembered and studied.

Legacy

Postage and Coin Commemorations

Franklin Pierce’s legacy is marked by his image appearing on a U.S. postage stamp in 1938 and a Presidential Dollar Coin in 2010. Despite these honors, his presidency is widely criticized as one of the least successful in American history, largely due to his handling of key issues that led to the Civil War.

Historical Assessment

Pierce’s presidency is often cited as a significant failure in American history. He is frequently ranked among the worst U.S. presidents, reflecting his inability to manage the sectional tensions that escalated into the Civil War. In C-SPAN’s surveys of presidential rankings, Pierce has been placed near the bottom, illustrating his poor historical reputation.

Controversial Policies

A major factor in Pierce’s negative legacy was his endorsement of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed the expansion of slavery into new territories and contributed to the violent conflicts in Kansas. This act, combined with his support for the pro-slavery policies, greatly damaged his reputation and the Democratic Party’s standing.

Historians’ Perspectives

Historians have been critical of Pierce’s presidency. Eric Foner described his administration as disastrous, noting its role in the collapse of the Jacksonian party system. Roy F. Nichols highlighted Pierce’s inability to balance conflicting interests and his failure to grasp the depth of Northern opposition to slavery. According to Nichols, Pierce’s lack of decisiveness and political skills contributed to his ineffective leadership.

David Potter focused on the negative impact of the Ostend Manifesto and the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which he believed were significant contributors to the discrediting of Manifest Destiny and “popular sovereignty” as political doctrines. Conversely, historian Kenneth Nivison viewed Pierce’s foreign policy more favorably, suggesting it laid groundwork for future American expansionism.

Alternative Views

Some scholars argue that Pierce’s actions were attempts to preserve the Union rather than to exacerbate divisions. Peter A. Wallner suggested that while Pierce’s presidency is often criticized for contributing to the Civil War, his intentions were to find a middle ground and avoid conflict. Larry Gara similarly contended that while Pierce struggled with the challenges of his time, he made notable achievements in foreign policy and trade, though his domestic policies exacerbated sectional tensions.

Final Years and Death

Pierce’s final years were marked by personal loss and declining health. He remained politically active to some extent, expressing criticism of Lincoln’s administration and supporting Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction policies. Pierce died on October 8, 1869, at the age of 64. His legacy remains contentious, reflecting a presidency that struggled to address the nation’s most pressing issues of the time.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franklin_Pierce