James Buchanan was the 15th President of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. Born on April 23, 1791, in Cove Gap, Pennsylvania, he was the only president who never married. Buchanan’s presidency is often criticized for his inability to prevent the country from sliding into civil war. He believed that states had the right to secede but that the federal government had no authority to prevent them from doing so. This indecisive stance contributed to the outbreak of the American Civil War shortly after he left office.

Buchanan’s time in office was marked by significant events such as the Dred Scott decision, which ruled that African Americans could not be citizens and that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the territories. He also faced challenges related to the tensions between the North and South, the financial Panic of 1857, and issues regarding the expansion of slavery.

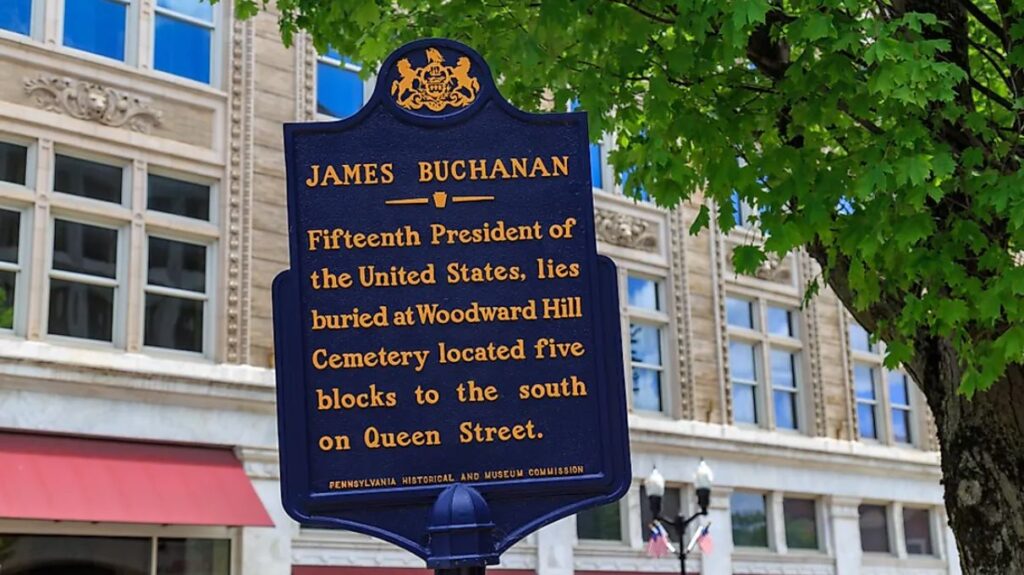

James Buchanan passed away on June 1, 1868, at his home in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. His legacy remains controversial, often ranked among the least effective presidents in U.S. history due to his failure to address the nation’s deepening divisions.

Early Life

Birth and Heritage

James Buchanan Jr. was born on April 23, 1791, into a Scottish-Irish family in a log cabin at Stony Batter farm, near Cove Gap in the Allegheny Mountains of southern Pennsylvania. He was the last U.S. president born in the 18th century. Buchanan was the eldest son in a family of eleven children, with six sisters and four brothers. His father, James Buchanan Sr., hailed from just outside Ramelton, a small town in County Donegal, Ireland. The elder Buchanan emigrated to the United States in 1783 from Derry.

The Buchanan family belonged to the Clan Buchanan, a group that had moved from the Scottish Highlands to Ulster in Ireland during the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century. They later emigrated in large numbers to America due to poverty and persecution for their Presbyterian faith.

Early Life and Education

Shortly after his birth, Buchanan’s family moved to a farm near Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, eventually settling in the town itself in 1794. His father became a prosperous merchant, farmer, and real estate investor. Buchanan credited his mother with his early education and his father with shaping his character. His mother engaged him in political discussions and had a keen interest in poetry, often quoting poets like John Milton and William Shakespeare.

Buchanan attended the Old Stone Academy in Mercersburg before enrolling at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In 1808, he nearly faced expulsion for unruly behavior, including drinking in taverns and causing disturbances. However, he was given another chance and graduated with honors in 1809. He then moved to Lancaster to study law under the mentorship of James Hopkins, where he studied the United States Code, the Constitution, and legal scholars like William Blackstone.

Early Law Practice and Political Involvement

Law Career and Masonic Involvement

Buchanan passed the bar exam in 1812 and established a successful legal practice in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, even as the state capital moved to Harrisburg. His income grew substantially, reaching over $11,000 annually by 1821 (equivalent to about $250,000 in 2023). He also became a Freemason, serving as the Worshipful Master of Masonic Lodge No. 43 in Lancaster and as a District Deputy Grand Master.

Political Career and War of 1812

Buchanan was active in the Federalist Party, supporting federal funding for infrastructure, import duties, and the re-establishment of a central bank. He became a vocal critic of Democratic-Republican President James Madison during the War of 1812. Although he did not serve in the military, he participated in activities such as stealing horses for the United States Army during the British occupation. He was the last U.S. president to be involved in the War of 1812.

Pennsylvania House of Representatives

In 1814, Buchanan was elected as a Federalist to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, becoming its youngest member. He served until 1816 while continuing his lucrative law practice. During his time in office, he defended District Judge Walter Franklin in an impeachment trial, arguing that impeachment should be reserved for judicial crimes and clear violations of the law.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

- 13th President of the United States

- 14th President of the United States

- 15th President of the United States

Congressional Career

U.S. House of Representatives

In the 1820 congressional elections, James Buchanan secured a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, representing Pennsylvania. His election was marred by tragedy, as his father passed away in a carriage accident shortly after his victory. Buchanan became a prominent figure in the “Amalgamator party,” a faction of Pennsylvanian politics that included both Democratic-Republicans and former Federalists. This faction was influential during the transition from the First Party System to the Era of Good Feelings, where Democratic-Republicans dominated. Buchanan’s early political alignment with the Federalist Party was short-lived; he eventually opposed a nativist Federalist bill and switched to supporting Democratic-Republicans.

During the 1824 presidential election, Buchanan initially supported Henry Clay but shifted his allegiance to Andrew Jackson when it became clear that Jackson had widespread support in Pennsylvania. Despite supporting Jackson, Buchanan’s mediation efforts between Clay and Jackson led to a strained relationship with Jackson. As a Representative, Buchanan was a staunch defender of states’ rights and forged strong connections with southern Congressmen, often viewing New England Congressmen as radicals. He played a key role in establishing a Democratic coalition in Pennsylvania, bringing together former Federalist farmers, Philadelphia artisans, and Ulster-Scots-Americans. In the 1828 presidential election, Buchanan helped secure Pennsylvania for Jackson, and the Jacksonian Democrats won a significant victory in the parallel congressional elections.

One of Buchanan’s notable contributions during his time in the House was his role as prosecutor in the impeachment trial of federal district judge James H. Peck, though the Senate ultimately acquitted Peck. Buchanan served on the Agriculture Committee and later became Chairman of the Judiciary Committee. By 1831, Buchanan declined a nomination for the 22nd United States Congress, signaling a temporary withdrawal from political life despite his aspirations. He remained a significant figure in Pennsylvania politics, with some Democrats considering him for the vice presidency in the 1832 election.

Minister to Russia

After Andrew Jackson’s re-election in 1832, Buchanan was appointed as the United States Ambassador to Russia, a position that served as a form of political exile orchestrated by Jackson, who viewed Buchanan as untrustworthy. Despite his initial reluctance, Buchanan accepted the role and focused on negotiating a trade and shipping treaty with Russia. While successful in some aspects, his efforts to secure a comprehensive agreement on free merchant shipping with Foreign Minister Karl Nesselrode were complicated by Buchanan’s prior criticisms of Tsar Nicholas I’s despotism.

U.S. Senator

Upon returning from Russia, Buchanan was elected by the Pennsylvania state legislature to the U.S. Senate, replacing William Wilkins. Buchanan, a Jacksonian Democrat, opposed the re-chartering of the Second Bank of the United States and worked to expunge a congressional censure of Jackson related to the Bank War. He served in the Senate from 1834 to 1845, adhering strictly to Pennsylvania State Legislature’s guidelines, even when it conflicted with his public positions. Buchanan’s senatorial career was marked by his commitment to states’ rights and the ideology of Manifest Destiny. He declined President Martin Van Buren’s offer to become United States Attorney General and chaired influential Senate committees, including the Committee on the Judiciary and the Committee on Foreign Relations.

Buchanan was a vocal critic of the Webster–Ashburton Treaty, believing it conceded too much land to the United Kingdom, and supported the annexation of the Republic of Texas and the acquisition of the entire Oregon Territory. He opposed the gag rule proposed by John C. Calhoun, which aimed to suppress anti-slavery petitions, arguing instead that the issue of slavery was a matter for individual states to decide. Although he positioned himself as a potential alternative to Martin Van Buren in the 1844 Democratic National Convention, the nomination ultimately went to James K. Polk.

Presidency of James Buchanan (1857–1861)

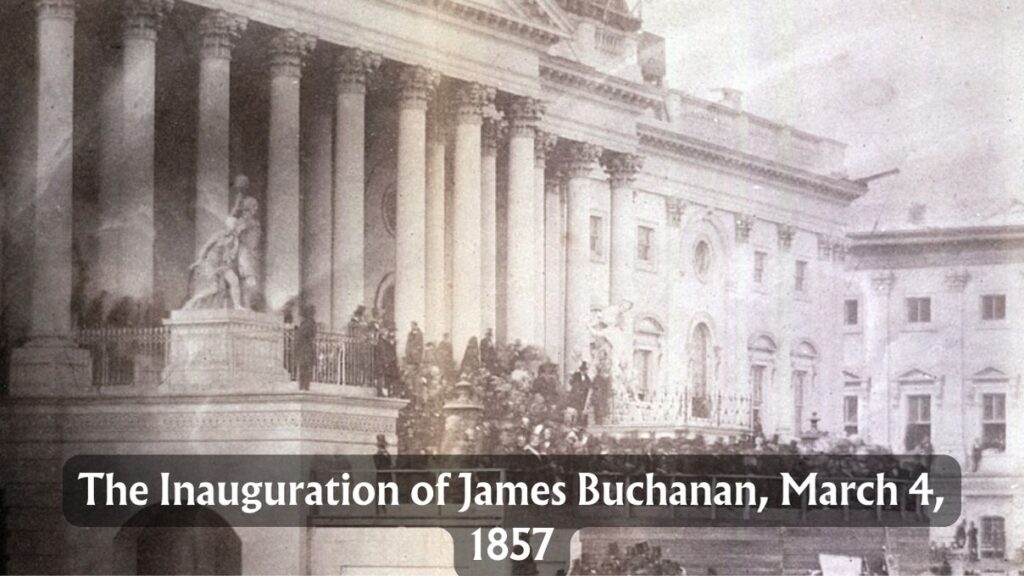

Inauguration and Early Presidency

James Buchanan was inaugurated on March 4, 1857, taking the oath of office from Chief Justice Roger B. Taney. In his inaugural address, Buchanan committed to serving only one term and expressed deep concern about the escalating divisions over slavery. He asserted that Congress should not intervene in determining the status of slavery in states or territories, advocating for the principle of popular sovereignty as established by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Buchanan also suggested that a federal slave code should be enacted to protect slaveowners’ rights in federal territories and hinted at the impending Supreme Court case, Dred Scott v. Sandford, which he believed would resolve the issue of slavery.

Dred Scott Case and Buchanan’s Influence

Buchanan’s inaugural address was notably influenced by his advance knowledge of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Dred Scott case. Associate Justice Robert C. Grier, a Pennsylvanian like Buchanan, had leaked the forthcoming decision to him. Buchanan’s address suggested that the issue of slavery would soon be “speedily and finally settled” by the Supreme Court. Historians, including Paul Finkelman, argue that Buchanan’s advance knowledge and public support of the decision undermined judicial propriety and intensified national tensions, contributing to the outbreak of the Civil War.

Cabinet and Administration

Buchanan aimed to create a harmonious cabinet but faced significant challenges. His cabinet included:

| Office | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| President | James Buchanan | 1857–1861 |

| Vice President | John C. Breckinridge | 1857–1861 |

| Secretary of State | Lewis Cass | 1857–1860 |

| Jeremiah S. Black | 1860–1861 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Howell Cobb | 1857–1860 |

| Philip Francis Thomas | 1860–1861 | |

| John Adams Dix | 1861 | |

| Secretary of War | John B. Floyd | 1857–1860 |

| Joseph Holt | 1861 | |

| Attorney General | Jeremiah S. Black | 1857–1860 |

| Edwin Stanton | 1860–1861 | |

| Postmaster General | Aaron V. Brown | 1857–1859 |

| Joseph Holt | 1859–1860 | |

| Horatio King | 1861 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Isaac Toucey | 1857–1861 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Jacob Thompson | 1857–1861 |

Despite Buchanan’s efforts, the cabinet included several Southern slaveholders who later supported the Confederacy, and his appointments led to friction, particularly with Vice President Breckinridge and influential figures like Stephen A. Douglas.

Judicial Appointments

Buchanan appointed Nathan Clifford to the Supreme Court and seven federal judges to district courts and the Court of Claims. His judicial appointments, particularly his involvement in the Dred Scott case, were controversial and seen as exacerbating the national crisis.

Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857, triggered by the insolvency of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company, led to widespread bank failures and business bankruptcies. Buchanan, adhering to Jacksonian Democracy principles, refrained from economic stimulus measures, exacerbating public suffering and resulting in a significant increase in the federal budget deficit.

Utah War

The Utah War, sparked by tensions between Brigham Young’s followers and federal representatives, was an attempt by Buchanan to replace Young as governor of Utah Territory. The conflict included the Mountain Meadows massacre and resistance from Mormons. Buchanan’s military response and subsequent peace negotiations resolved the immediate conflict but left lingering issues.

Transatlantic Telegraph Cable

In 1858, Buchanan received the first official telegram transmitted across the Atlantic from Queen Victoria, marking a significant achievement in communication and symbolizing hope for enduring peace and friendship between nations.

Bleeding Kansas and Constitutional Disputes

The Kansas-Nebraska Act led to violent clashes over the status of slavery in Kansas, known as “Bleeding Kansas.” Buchanan’s endorsement of the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution and efforts to manipulate congressional approval were contentious and contributed to political divisions within the Democratic Party.

1858 Mid-Term Elections and Foreign Policy

Buchanan’s foreign policy efforts included seeking American dominance in Central America, acquiring Cuba, and negotiating with foreign powers. His administration faced challenges, including the unsuccessful bid to purchase Alaska and conflicts over trade agreements.

Covode Committee Investigation

The Covode Committee investigated alleged corruption in Buchanan’s administration, focusing on patronage and bribery related to the Lecompton Constitution. Although the committee did not establish grounds for impeachment, it highlighted issues of corruption and abuse of power within Buchanan’s administration.

Buchanan’s presidency was marked by intense political conflicts, economic challenges, and significant contributions to the prelude of the Civil War. His policies and decisions had lasting impacts on the nation’s trajectory leading up to the Civil War.

Election of 1860: A Crucial Turning Point in American History

As the United States approached the pivotal Election of 1860, the political landscape was fraught with tension and division. President James Buchanan, who had pledged in his inaugural address not to seek re-election, was true to his word. In a gesture reflecting his relief, Buchanan told his successor, “If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man.”

A Democratic Party in Turmoil

The 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston was a reflection of the nation’s fractured political climate. The party was deeply divided over the contentious issue of slavery in the territories. Stephen A. Douglas, who had initially led in votes, failed to secure the necessary two-thirds majority despite numerous ballots. The convention, after 53 ballots, adjourned and reconvened in Baltimore in June. Douglas eventually secured the nomination, but his victory did not quell the dissent. Southern Democrats, disenchanted with the outcome, nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge as their candidate. This schism within the party further fragmented its support base.

The fractured Democrats, unable to present a united front, paved the way for Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln to win the presidency. Lincoln’s victory was solidified by his substantial support in the North, which translated into an Electoral College majority. Buchanan’s presidency marked the last time a Democrat would occupy the White House until Grover Cleveland’s election in 1884.

Secession Crisis and Buchanan’s Response

The election of Lincoln triggered an escalating secession crisis. By October, General Winfield Scott, an opponent of Buchanan, warned of imminent secession by at least seven states. Scott’s recommendation to deploy federal troops and artillery to protect federal property went unheeded by Buchanan, who distrusted Scott and ignored his warnings. Instead, Buchanan instructed Secretary of War John B. Floyd to reinforce southern forts, but Floyd, influenced by his own Southern sympathies, persuaded Buchanan to revoke the order.

As secessionist fervor reached a climax, Buchanan addressed Congress on December 10, 1860. In his message, Buchanan declared that while states did not have the right to secede, the federal government lacked the power to prevent it. He placed the blame for the crisis on Northern interference with Southern slavery issues and suggested a constitutional amendment to protect slavery and strengthen fugitive slave laws. This address was met with sharp criticism from both sides—Northerners criticized him for failing to act decisively, while Southerners felt betrayed by his denial of their right to secede.

The Road to War

Despite Buchanan’s efforts, including his support for compromise amendments and negotiations, six additional slave states seceded by the end of January 1861. Buchanan replaced Southern cabinet members with loyal Unionists, but his presidency continued to struggle with the escalating crisis. Buchanan’s decision to reinforce Fort Sumter, although initially intended, was hampered by logistical failures and resulted in the ship Star of the West returning without supplies or troops. As the nation teetered on the brink of civil war, Buchanan’s attempts at compromise failed to prevent the inevitable conflict.

New States Admitted to the Union

During Buchanan’s presidency, three new states were admitted to the Union:

- Minnesota – May 11, 1858

- Oregon – February 14, 1859

- Kansas – January 29, 1861

Retirement and Legacy

Upon leaving office, Buchanan retreated to his home in Wheatland. The Civil War began shortly after his retirement, and Buchanan expressed his support for the Union cause, though he opposed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. His post-presidency years were marred by controversy and criticism, as Buchanan became a target of harsh criticism and accusations of collusion with the Confederacy. His memoir, Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of Rebellion, published in 1866, defended his actions and blamed Republicans and abolitionists for the secession crisis.

Buchanan’s final years were marked by illness and continued defense of his legacy. He died on June 1, 1868, at the age of 77, from respiratory failure. His life and presidency remain subjects of debate, particularly regarding his handling of the secession crisis and his personal views on slavery.

Personal Life and Legacy

Buchanan’s personal life has been the subject of speculation. His bachelorhood and close relationship with William Rufus King led to various rumors and debates about his sexuality. Buchanan’s relationships and personal choices continue to spark interest and discussion among historians.

In summary, the election of 1860 and Buchanan’s final months in office were crucial in shaping the course of American history, setting the stage for the Civil War and leaving a complex legacy of political and personal challenges.

James Buchanan’s legacy as the 15th President of the United States is a subject of significant historical debate and scrutiny. Here’s a summary of his reputation and how he’s remembered:

Historical Reputation

- Criticism and Rankings:

- Buchanan is widely criticized for his lack of decisive action during the secession crisis leading up to the Civil War. Historians often rank him among the least effective U.S. presidents, highlighting his poor leadership and inability to address the nation’s growing divisions.

- Surveys of historians and political scientists frequently place Buchanan at the bottom in terms of vision, domestic leadership, and moral authority.

- Biographical Perspectives:

- Philip S. Klein (1962): Klein acknowledged Buchanan’s challenges during a tumultuous period but suggested that his talents were overshadowed by the crisis and Lincoln’s leadership.

- Jean Baker (2004): Baker criticized Buchanan for his perceived favoritism towards the South and described him as a stubborn ideologue whose principles were detrimental during a national crisis. She argued that his actions bordered on treason.

- Alternative Views:

- Some historians, like Robert May, argue that Buchanan’s policies were not explicitly pro-slavery, though his overall handling of the presidency remains controversial.

Memorials

- Washington, D.C.:

- A bronze and granite memorial was dedicated in 1930 in Meridian Hill Park, featuring a statue of Buchanan and classical figures representing law and diplomacy.

- Stony Batter, Pennsylvania:

- A monument built between 1907 and 1911 on the site of Buchanan’s birthplace includes a large pyramid structure marking the location of his original cabin.

- Counties and Cities:

- Several counties and towns in various states (Iowa, Missouri, Virginia, Michigan, Indiana, Georgia, Wisconsin) are named in his honor.

- James Buchanan High School:

- Located in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, this rural high school is named after the former president.

Popular Culture

- “Raising Buchanan” (2019):

- Buchanan is portrayed by René Auberjonois in this film, reflecting his continued presence in popular culture.

Buchanan’s legacy remains complex and debated, with significant criticisms overshadowing his accomplishments and leading to a generally negative historical assessment.