James Knox Polk, born on November 2, 1795, in Pineville, North Carolina, was a prominent American lawyer and politician. Serving as the 11th President of the United States from 1845 to 1849, Polk was also notable for his roles as the 13th Speaker of the House of Representatives and the 9th Governor of Tennessee.

James K. Polk was the 11th President of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He is known for his expansionist policies, which led to the annexation of Texas, the Oregon Treaty, and the Mexican-American War, through which the United States acquired vast territories in the Southwest. Polk was a strong advocate of Manifest Destiny, the belief that American settlers were destined to expand across North America. His presidency also saw significant domestic reforms, including the establishment of the U.S. Naval Academy and the Smithsonian Institution.

A protege of Andrew Jackson and a staunch advocate of Jacksonian democracy within the Democratic Party, Polk’s presidency marked a significant expansion of U.S. territory. His tenure saw the annexation of the Republic of Texas, the Oregon Territory, and the Mexican Cession following the Mexican-American War.

Before his presidency, Polk established a successful law practice in Tennessee and served in its state legislature. Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1825, he rose to prominence as a strong supporter of Jackson, eventually becoming Speaker of the House in 1835, a rare achievement later mirrored by his presidency.

Polk’s election in 1844 as a dark-horse candidate underscored his political acumen. His administration prioritized territorial expansion and economic reforms, including the Walker tariff of 1846 and the reestablishment of the Independent Treasury system.

Committed to a single term as promised during his campaign, Polk left office in 1849. He passed away shortly after from cholera in Nashville, Tennessee, leaving a legacy marked by his ambitious expansionist policies and their lasting impact on U.S. territorial borders.

While admired for his effective leadership in achieving major national goals, Polk’s presidency has also been scrutinized for exacerbating divisions over slavery and precipitating tensions that ultimately led to the Civil War.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

James Knox Polk: Early Life and Formative Years

James Knox Polk, born on November 2, 1795, entered the world in a humble log cabin in Pineville, North Carolina. He was the eldest of ten children in a farming family deeply rooted in Scots-Irish heritage. His father, Samuel Polk, a farmer and slaveholder, and his mother, Jane, instilled in him strong Calvinistic values from a young age, emphasizing discipline, hard work, and a sense of individualism.

Reconstruction of the log cabin in Pineville, North Carolina where Polk was born

The Polk family’s roots in America traced back to the late 17th century, initially settling in Maryland before migrating to Pennsylvania and eventually to the hills of Carolina. Raised in a Presbyterian household, young James was influenced by his mother’s devout beliefs, contrasting with his father’s more skeptical views on organized religion.

Despite facing early health challenges, including a serious medical procedure in his youth, Polk’s resilience grew as he matured. His education began at a Presbyterian academy, followed by enrollment at Bradley Academy in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where his academic promise flourished.

In 1816, Polk enrolled at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he excelled academically and honed his oratory skills in debates at the Dialectic Society. His time at university solidified his political leanings, shaped by discussions on democratic principles and critiques of monarchical tendencies in American leadership.

Returning to Tennessee after graduation, Polk embarked on a legal career under the tutelage of Felix Grundy, a renowned trial attorney. His early success in law paralleled his growing involvement in Tennessee’s political landscape, marked by his election as clerk of the Tennessee State Senate in 1819.

During the severe economic downturn of the Panic of 1819, Polk’s legal practice thrived, bolstering his financial stability while fueling his political ambitions. His astute handling of legal cases related to the economic crisis further solidified his reputation as a capable lawyer and emerging political figure.

James Knox Polk’s early life and educational journey underscored his resilience, intellectual vigor, and early immersion in the political currents shaping America in the early 19th century.

James K. Polk’s early political career

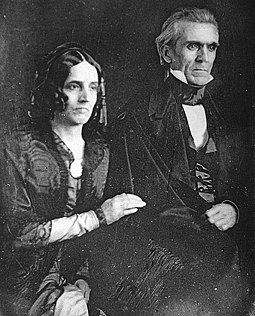

1846–49 daguerreotype of James K. Polk and Sarah Childress Polk

As the Tennessee legislature adjourned in September 1822, James K. Polk set his sights on a seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives, with the election slated for August 1823. With nearly a year to campaign, Polk, already active in local Masonic circles, further bolstered his profile by serving as a captain in the Tennessee militia’s cavalry regiment of the 5th Brigade. His subsequent appointment as a colonel on Governor William Carroll’s staff earned him the enduring moniker “Colonel Polk.” Despite facing incumbent William Yancey, Polk’s energetic campaigning and compelling oratory, which earned him the nickname “Napoleon of the Stump,” resonated with voters, including many from his own Polk clan.

During this period, Polk’s personal life intertwined with his political ambitions. Beginning in early 1822, he courted Sarah Childress, whom he married on January 1, 1824, in Murfreesboro. Educated beyond the norm for women of her time, Sarah, from one of Tennessee’s most prominent families, played a pivotal role in James’s career. She provided counsel on policy matters, assisted with his speeches, and actively supported his campaigns, her grace and intelligence complementing his more reserved demeanor.

Politically, Polk aligned with Andrew Jackson, supporting his presidential ambitions and breaking from his usual allies to endorse Jackson for U.S. senator in 1823. This alliance bolstered Jackson’s presidential prospects and marked the beginning of a lasting political partnership that shaped Polk’s career. Known as “Young Hickory” in honor of Jackson’s moniker “Old Hickory,” Polk’s political trajectory became intricately tied to Jackson’s legacy.

Amidst these developments, Polk’s election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1825 marked a significant step in his career, representing Tennessee’s 6th congressional district. His vigorous campaigning and victory in the face of opposition underscored his growing influence and determination to champion Jacksonian principles in national politics.

Jackson disciple

Upon arriving in Washington, D.C. for Congress’s session in December 1825, James K. Polk lodged at Benjamin Burch’s boarding house alongside fellow Tennessee representatives, including Sam Houston. Polk delivered his inaugural address on March 13, 1826, advocating for the abolition of the Electoral College in favor of direct popular vote for the presidency. His staunch opposition to what he perceived as the corrupt deal between Adams and Clay marked him as a vocal critic of the Adams administration, consistently voting against its policies. During this period, Sarah Polk initially remained in Columbia but joined him in Washington from December 1826, offering vital support in managing his correspondence and attending his speeches.

Re-elected in 1827, Polk continued his opposition to the Adams administration, maintaining close ties with Andrew Jackson. Serving as an advisor during Jackson’s successful presidential campaign in 1828, Polk emerged as one of his most steadfast supporters in Congress. He played a pivotal role in thwarting federally-funded “internal improvements,” such as the proposed Buffalo-to-New Orleans road, and endorsed Jackson’s veto of the Maysville Road bill in May 1830, arguing it exceeded constitutional limits. While some attributed the veto message to Polk, he clarified it was solely Jackson’s work.

The house where Polk spent his young adult life before his presidency, in Columbia, Tennessee, is his only private residence still standing. It is now known as the James K. Polk Home.

During the “Bank War,” Polk aligned closely with Jackson in opposing the re-chartering of the Second Bank of the United States, led by Nicholas Biddle. Critical of its perceived monopoly and influence over national credit, Polk, serving on the House Ways and Means Committee, authored a dissenting report against renewing the bank’s charter. Despite Congress passing the bill in 1832, Jackson’s veto prevailed, bolstering his popularity for re-election.

Polk’s stance mirrored Southern sentiment, favoring low tariffs and initially sympathizing with John C. Calhoun during the Nullification Crisis. However, he ultimately sided with Jackson in supporting federal authority against South Carolina’s nullification efforts, advocating for a compromise tariff passed by Congress to resolve the dispute.

Ways and Means Chair and Speaker of the House

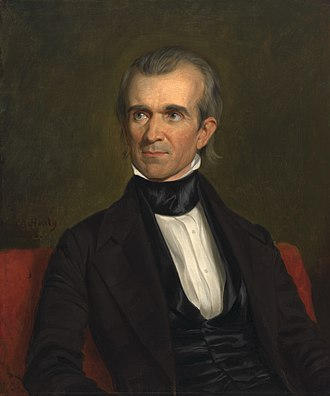

Oil on canvas portrait by George Peter Alexander Healy

In December 1833, James K. Polk secured his fifth consecutive term and assumed the chairmanship of Ways and Means, a pivotal role within the House of Representatives, backed by President Jackson. In this capacity, Polk staunchly supported Jackson’s efforts to withdraw federal funds from the Second Bank. His committee issued reports scrutinizing the bank’s finances and endorsing Jackson’s actions against it. By April 1834, the Ways and Means Committee proposed legislation to regulate state deposit banks, facilitating Jackson’s move to deposit funds in state banks (known as pet banks). Polk also successfully pushed through legislation authorizing the sale of the government’s stock in the Second Bank.

When Speaker of the House Andrew Stevenson resigned in June 1834 to become Minister to the United Kingdom, Jackson supported Polk’s bid for the speakership. Polk competed against John Bell, Richard Henry Wilde, and Joel Barlow Sutherland, ultimately losing after ten ballots to Bell, who garnered support from Jackson’s opponents.

However, Jackson persisted in securing Polk’s speakership for the next Congress starting in December 1835, rallying support and ensuring Polk’s victory over Bell. During this period, Polk reached the pinnacle of his congressional career, wielding considerable influence in advancing Jacksonian Democracy on the House floor. Assisted by his wife Sarah, Polk also became a prominent figure in Washington’s social circles, moving from a boarding house to their own residence on Pennsylvania Avenue.

In the 1836 presidential election, Polk supported Vice President Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s chosen successor, against multiple Whig candidates. Despite Van Buren’s victory, Whig strength in Tennessee, fueled by discontent over the destruction of the Second Bank, led many to favor Senator Hugh Lawson White over Van Buren.

As Speaker of the House, Polk vigorously championed Jackson’s and later Van Buren’s policies, appointing Democratic committee chairs and enforcing measures such as the “gag rule” on slavery petitions. The economic challenges following the Panic of 1837 dominated his tenure, prompting debates over issues like the Specie Circular and the Independent Treasury system. Despite his efforts, the Democrats faced setbacks in subsequent elections, influencing Polk’s decision not to seek re-election as Speaker in 1839. Instead, he turned his focus to a gubernatorial bid in Tennessee, driven by his burgeoning presidential ambitions, aware that no former Speaker had ascended to the presidency (a distinction he would ultimately achieve).

James K. Polk

Governor of Tennessee

In 1835, the Democratic Party of Tennessee suffered its first gubernatorial defeat in history, prompting James K. Polk to return home and lead the party’s resurgence. Tennessee, once a stronghold of Jacksonian Democrats, had shifted allegiance to the Whigs under Governor Newton Cannon. As the head of the state Democratic Party, Polk embarked on his inaugural statewide campaign, challenging incumbent Cannon, who sought a third term.

Polk focused his campaign on national issues while Cannon emphasized state matters. Initially outmaneuvered by Polk in debates, Cannon retreated to Nashville under the guise of official duties. Meanwhile, Polk tirelessly campaigned across Tennessee, aiming to broaden his recognition beyond Middle Tennessee. As the election day approached on August 1, 1839, Polk prevailed over Cannon by a slim margin of 54,102 to 51,396 votes. The Democrats also regained control of the state legislature and secured three congressional seats.

Although the Tennessee governorship held limited power without veto authority and minimal patronage opportunities, Polk viewed it as a stepping stone for his national ambitions. He sought nomination as Vice President under Martin Van Buren in the 1840 Democratic National Convention, positioning himself as an alternative to Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson. Despite initial hopes, Polk withdrew his candidacy when Johnson remained popular within the party, especially among Southern Democrats uncomfortable with Johnson’s personal controversies.

The 1840 election brought disappointment to Polk as William Henry Harrison’s Whig campaign triumphed nationally, leaving Van Buren defeated. Polk’s governorship saw ambitious legislative efforts—regulating state banks, initiating internal improvements, and enhancing education—all stymied by legislative resistance amid the lingering economic downturn following the Panic of 1837.

Facing re-election in 1841, Polk encountered stiff opposition from James C. Jones, a spirited Whig newcomer known for his wit and support for distributing federal surplus revenues to the states and advocating for a national bank. Despite Polk’s earnest efforts and a rematch in 1843, he suffered consecutive defeats, signaling a challenging period in his political career.

Election of 1844

In 1835, the Democratic Party in Tennessee faced its first-ever loss in the gubernatorial race, prompting James K. Polk to return home and lead the party’s resurgence. Tennessee, previously a stronghold of Jacksonian Democrats, had shifted its allegiance to the Whigs under Governor Newton Cannon. As the leader of the state Democratic Party, Polk launched his inaugural statewide campaign, challenging incumbent Cannon, who sought a third term.

Polk focused his campaign on national issues, contrasting with Cannon’s emphasis on state matters. Initially outmatched by Polk in debates, Cannon withdrew to Nashville under the pretense of official duties. Meanwhile, Polk campaigned tirelessly across Tennessee, aiming to expand his recognition beyond Middle Tennessee. On Election Day, August 1, 1839, Polk narrowly defeated Cannon with 54,102 to 51,396 votes. The Democrats also regained control of the state legislature and secured three congressional seats.

Despite the limited power of the Tennessee governorship, lacking veto authority and with minimal patronage opportunities, Polk viewed it as a stepping stone for his national ambitions. He sought nomination as Vice President under Martin Van Buren at the 1840 Democratic National Convention, positioning himself as an alternative to Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson. However, Polk withdrew his candidacy when Johnson remained popular within the party, especially among Southern Democrats uncomfortable with Johnson’s personal controversies.

The 1840 election brought disappointment for Polk as William Henry Harrison’s Whig campaign triumphed nationally, resulting in Van Buren’s defeat. Polk’s governorship saw ambitious legislative efforts—including state bank regulation, internal improvements, and educational enhancements—all thwarted by legislative resistance amid the economic downturn following the Panic of 1837.

Facing re-election in 1841, Polk encountered formidable opposition from James C. Jones, a spirited Whig newcomer known for his wit and advocacy for distributing federal surplus revenues to states and promoting a national bank. Despite Polk’s determined efforts and a rematch in 1843, he suffered consecutive defeats, marking a challenging phase in his political career.

General election

In June 1834, rumors of James K. Polk’s presidential nomination reached Nashville, bringing joy to Andrew Jackson. Later that day, confirmed dispatches arrived in Columbia, where Polk received letters and newspapers detailing the events at Baltimore by June 6. He officially accepted his nomination via letter on June 12, emphasizing that he had never actively sought the office and committing to serve only one term.

Meanwhile, Silas Wright expressed bitterness over what he termed a “foul plot” against Martin Van Buren and demanded assurances from Polk of his loyalty to Van Buren before supporting Polk’s candidacy. Following the tradition of the time for presidential candidates to avoid overt campaigning, Polk remained in Columbia, refraining from public speeches. Instead, he engaged extensively in written correspondence with Democratic Party leaders to manage his campaign. Polk conveyed his positions through his acceptance letter and responses to citizen inquiries published in newspapers.

A potential challenge for Polk’s campaign centered on the tariff issue, specifically whether it should focus solely on revenue or include protective measures for American industries. Polk navigated this issue carefully in a published letter, maintaining his longstanding view that tariffs should fund government operations while hinting at support for “fair and just protection” of American interests, including manufacturers. Despite attempts by Whigs to press him for clarity during a visit from Giles County delegates in September, Polk stuck to his ambiguous stance, prompting criticism in Whig newspapers.

Another concern was President John Tyler’s third-party candidacy, which threatened to split the Democratic vote. Tyler, nominated by a faction of loyal officeholders, aimed to mobilize states’ rights supporters and populists. Andrew Jackson intervened decisively, using his influence to coax Tyler into withdrawing from the race. Jackson’s efforts included letters to his Cabinet friends assuring Tyler’s supporters of their welcome back into the Democratic Party fold. This strategic move aimed to consolidate Democratic support behind Polk, particularly for his pro-annexation stance on Texas.

Internal party discord also posed a challenge. Polk reconciled with John C. Calhoun after Francis Pickens, a former South Carolina congressman, mediated discussions in Tennessee and at Jackson’s Hermitage. Calhoun sought assurances from Polk on dissolving the Democratic Party’s Globe newspaper, opposing the 1842 tariff, and promoting Texas annexation. Satisfied with Polk’s commitments, Calhoun became a staunch supporter.

The campaign also faced contention over the issue of Texas annexation, exacerbated by Henry Clay’s vacillating stance. Despite Clay’s attempts to clarify his anti-annexation position in subsequent letters, his inconsistencies alienated supporters on both sides of the debate. Polk skillfully navigated these divisions, securing broad Southern Democratic support without alienating Northern leaders.

As the election neared, public sentiment increasingly favored Texas annexation, garnering support even among some Southern Whig leaders, disenchanted by Clay’s anti-annexation stance. The 1844 campaign was marked by acrimony, with both major candidates, including Polk, facing allegations ranging from dueling to cowardice. The most damaging smear involved the Roorback forgery, circulated in abolitionist newspapers, which falsely accused Polk of selling slaves branded with his initials. Despite Democratic protests and retractions, the smear impacted voter perception, particularly in critical states like Ohio.

The election results, held between November 1 and 12, 1844, saw Polk win with 49.5% of the popular vote and 170 electoral votes out of 275. His victory marked the first instance of a president-elect losing his home state (Tennessee) and birth state (North Carolina). Nonetheless, Polk carried key states like Pennsylvania and New York, where antislavery candidate James G. Birney siphoned votes from Henry Clay. Had Clay won New York, he would have secured the presidency, highlighting the pivotal role of third-party dynamics in the election.

Presidency (1845–1849)

With a narrow win in the popular vote but a decisive Electoral College victory (170–105), Polk began implementing his campaign promises. Under his leadership, the U.S. population, which had been doubling every twenty years since the American Revolution, matched Great Britain’s demographic levels. Technological progress continued with railroad expansion and increased telegraph use, fueling a drive for expansionism. However, sectional tensions also grew during his presidency.

Polk’s administration focused on four main goals:

- Reestablish the Independent Treasury System, which the Whigs had abolished.

- Reduce tariffs.

- Acquire the Oregon Country.

- Secure California and its harbors from Mexico.

While his domestic objectives aligned with past Democratic policies, achieving these foreign policy goals would mark significant American territorial gains since the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

Transition, inauguration and appointments

Polk assembled a geographically diverse Cabinet, ensuring representation from New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and his home state of Tennessee. While he desired a completely new Cabinet, avoiding any lingering officials from Tyler’s administration, he handled the situation delicately. Tyler’s final Secretary of State, Calhoun, was willing to step down without issue when approached by Polk’s representatives.

Although Polk avoided appointing potential presidential contenders to his Cabinet, he selected James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, known for his presidential ambitions, as Secretary of State. Cave Johnson from Tennessee, a close ally of Polk, was named Postmaster General, and historian George Bancroft, who had supported Polk’s nomination, became Secretary of the Navy. Polk’s choices were approved by Andrew Jackson, who passed away in June 1845.

John Y. Mason of Virginia, a longtime friend and political ally of Polk, was not originally on the list but was appointed Attorney General at the last minute due to factional politics and Tyler’s efforts to address the Texas issue. Polk also appointed Mississippi Senator Walker as Secretary of the Treasury and New York’s William Marcy as Secretary of War. The Cabinet functioned smoothly, with few changes needed; Bancroft was later moved to a diplomatic post in Britain.

As Tyler’s term ended, he worked to finalize Texas’s annexation. After the Senate rejected an earlier treaty, Tyler pushed for a joint resolution to admit Texas as a state. Polk helped navigate this resolution through Congress. Tyler, unsure whether to sign the resolution himself or leave it to Polk, eventually offered annexation on his final day in office, March 3, 1845.

Before taking office, Polk assured Cave Johnson of his intent to be actively involved in presidential duties. Known for his diligent work ethic, Polk spent long hours managing government affairs personally. At 49, he became the youngest president at that time. His inauguration was notably the first covered by telegraph and illustrated in a newspaper.

In his inaugural address, delivered in the rain, Polk affirmed his support for Texas’s annexation and echoed Jackson’s principles, emphasizing national unity. He expressed opposition to a national bank while supporting a tariff with incidental protection. Although he did not explicitly mention slavery, he defended the institution as protected by the Constitution.

Polk dedicated the latter part of his speech to foreign policy and expansion, celebrating Texas’s annexation and asserting America’s rights in Oregon Country. For personal assistance, he appointed his nephew, J. Knox Walker, as his personal secretary, given that Polk had no other staff at the White House. Walker managed his duties effectively, living at the White House with his family.

Foreign policy

Partition of Oregon Country

Britain and the U.S. both laid claim to the Oregon Country based on explorer voyages, while Russia and Spain had relinquished their weaker claims. The rights of the indigenous peoples were not considered in these claims.

Instead of resorting to conflict over this remote, unsettled land, Washington and London chose negotiation. Previous U.S. administrations had suggested dividing the territory at the 49th parallel, but Britain, with its commercial interests on the Columbia River, found this unacceptable. Britain’s preferred division was also rejected by Polk, as it would have given Puget Sound and all lands north of the Columbia River to Britain. Furthermore, Britain opposed extending the 49th parallel to the Pacific, which would isolate its settlements along the Fraser River.

Edward Everett, Tyler’s envoy in London, had informally suggested dividing the territory at the 49th parallel while granting Vancouver Island to Britain for Pacific access. However, when the new British minister in Washington, Richard Pakenham, arrived in 1844, he encountered strong American interest in the entire Oregon Country, which extended up to 54 degrees, 40 minutes north latitude. Despite Oregon not being a major issue in the 1844 election, the surge of American settlers and growing expansionist sentiment made reaching a treaty more pressing.

Both nations saw the territory as a critical geopolitical asset. In his inaugural address, Polk declared the U.S. claim to the land as “clear and unquestionable,” prompting British leaders to threaten war if Polk pursued full control. Although the Democratic platform supported a full claim, Polk refrained from making such an assertion in his speech. Despite his assertive rhetoric, he saw war over Oregon as unwise and began negotiations with Britain. Polk proposed a division along the 49th parallel, which Pakenham rejected outright. Buchanan, wary of a two-front war with Mexico and Britain, was cautious, but Polk was willing to risk both conflicts for a favorable settlement.

In December 1845, Polk requested Congressional approval to notify Britain of his intention to end the joint occupancy of Oregon, quoting the Monroe Doctrine to assert America’s stance against European interference. Congress passed the resolution in April 1846, hoping for a peaceful resolution.

When British Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen learned of the rejected proposal, he urged the U.S. to reopen talks, but Polk insisted on a new British proposal. With Britain shifting towards free trade and valuing good relations with the U.S. over a distant territory, Aberdeen was keen on negotiations. By February 1846, the American minister in London was informed that Washington would favor a British proposal to divide the continent at the 49th parallel.

In June 1846, Pakenham presented a proposal to establish the boundary at the 49th parallel while Britain retained Vancouver Island and secured limited navigation rights on the Columbia River until 1859. Polk and his Cabinet were inclined to accept this offer. The Senate ratified the Oregon Treaty with a 41–14 vote. Polk’s readiness to risk war had alarmed many, but his firm negotiation tactics may have secured concessions from Britain that a more accommodating president might not have achieved.

Annexation of Texas

The annexation resolution signed by Tyler gave the president the option to either ask Texas to approve annexation or reopen negotiations; Tyler promptly chose the first option. Polk allowed this decision to proceed and assured that the U.S. would support Texas and set its southern border at the Rio Grande, as Texas claimed, rather than the Nueces River, as Mexico claimed. Public opinion in Texas strongly supported annexation.

In July 1845, a Texas convention ratified the annexation, which was subsequently approved by voters. By December 1845, Texas was admitted as the 28th state. However, Mexico, having severed diplomatic ties with the U.S. upon the passage of the joint resolution in March 1845, saw the annexation as an escalation of tensions, as it had never acknowledged Texan independence.

Mexican American War

Road to war

After the annexation of Texas in 1845, Polk began preparing for a possible conflict with Mexico. He dispatched an army to Texas, commanded by Brigadier General Zachary Taylor, and ordered both land and naval forces to be ready to respond to any Mexican aggression, while avoiding actions that could provoke war. Polk hoped Mexico would concede under pressure.

In late 1845, Polk sent John Slidell to Mexico with a proposal to purchase New Mexico and California for $30 million and to secure Mexico’s agreement on a Rio Grande border. However, Mexican sentiment was hostile, and President José Joaquín de Herrera refused to meet with Slidell. Herrera was soon overthrown in a military coup led by General Mariano Paredes, who was committed to reclaiming Texas. Slidell’s dispatches indicated that war was imminent.

Polk viewed the refusal to receive Slidell as a grave insult and a justification for war. He prepared to ask Congress for a declaration of war. By late March, General Taylor’s forces had reached the Rio Grande and set up camp across from Matamoros, Tamaulipas. In April, after Mexican General Pedro de Ampudia demanded Taylor’s withdrawal to the Nueces River, Taylor began blockading Matamoros. On April 25, a skirmish on the north side of the Rio Grande, known as the Thornton Affair, resulted in American casualties and heightened tensions.

By May 9, Polk reported the incident to Congress, claiming Mexico had “shed American blood on American soil.” The House of Representatives overwhelmingly approved a resolution declaring war and authorizing the recruitment of 50,000 volunteers. Although some senators, including Calhoun, questioned Polk’s account, the Senate passed the resolution by a 40–2 vote, with Calhoun abstaining, thus initiating the Mexican American War.

Course of the war

Following the early skirmishes, Taylor and much of his army moved away from the Rio Grande to secure their supply lines, leaving behind a temporary fort known as Fort Texas. As they made their way back to the river, Mexican forces under General Mariano Arista attempted to obstruct Taylor’s advance, while other Mexican troops laid siege to Fort Texas. This situation forced Taylor to launch an attack to relieve the fort.

In the Battle of Palo Alto, the first significant engagement of the conflict, Taylor’s forces decisively defeated Arista’s troops, sustaining only four casualties compared to the hundreds suffered by the Mexicans. The following day, Taylor led his army to another victory at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma, driving the Mexican forces from the field.

These early victories increased public support for the war, despite the deep divisions it caused within the country. Many Northern Whigs and others opposed the war, believing that Polk had manipulated national sentiment to expand slavery by instigating the conflict.

Polk was wary of his two senior generals, Major General Winfield Scott and Taylor, due to their Whig affiliations. Although he considered replacing them with Democrats, he feared Congressional disapproval. Polk offered Scott the position of chief commander in the war, which Scott accepted, despite their strained relationship.

Polk had previously been displeased with Scott’s delayed movement and his attempts to use congressional influence against Polk’s plans. Following Taylor’s victories, Polk decided to keep Taylor in command in the field and have Scott remain in Washington.

Polk also ordered Commodore Conner to allow Antonio López de Santa Anna to return from exile in Havana, hoping Santa Anna would negotiate a treaty ceding territory to the U.S. Polk sent envoys to Cuba to engage with Santa Anna, but Santa Anna returned to Mexico not to negotiate, but to rally defenses against the U.S. Polk was duped by Santa Anna, who prolonged the war by mobilizing Mexican resistance.

In response, Polk hardened his stance and ordered an American invasion of Mexico, beginning with a landing at Veracruz, the key Mexican port on the Gulf of Mexico. From Veracruz, U.S. troops advanced towards Mexico City. In September 1846, Taylor defeated a Mexican army led by General Pedro de Ampudia in the Battle of Monterrey but allowed Ampudia’s forces to withdraw, much to Polk’s frustration. Polk, believing Taylor had been insufficiently aggressive, offered the command of the Veracruz expedition to Scott.

Taylor, feeling undermined by Polk and fearing political machinations, disobeyed orders to stay near Monterrey and instead continued south, capturing the town of Saltillo. Taylor’s forces then engaged in the Battle of Buena Vista against a larger Mexican force led by Santa Anna. Despite initial reports suggesting a Mexican victory, Santa Anna retreated, with Mexican casualties significantly higher than American ones. Taylor’s heroism increased his popularity, though Polk preferred to credit the soldiers rather than the Whig general.

The turning point of the war came with the U.S. invasion of Mexico’s heartland. Scott landed at Veracruz in March 1847 and quickly took control of the city. Anticipating disease to weaken the U.S. troops, the Mexicans were nonetheless unable to prevent Scott’s advance. Polk sent Nicholas Trist, Buchanan’s chief clerk, to accompany Scott and negotiate peace terms. Trist was instructed to seek the cession of Alta California, New Mexico, Baja California, and recognition of the Rio Grande as Texas’s southern border, with a payment of up to $30 million.

In August 1847, Scott defeated Santa Anna at the Battles of Contreras and Churubusco as he moved towards Mexico City. With American forces at the city’s gates, Trist negotiated with Mexican commissioners, but initial offers were minimal. Scott captured Mexico City in mid-September.

This led to heated political debates in the U.S. about the extent of annexation, with some Whigs advocating for settling only the Texas border issue and others pushing for the annexation of all of Mexico. Opposition to the war was also vocal; Whig Congressman Abraham Lincoln introduced the “exact spot” resolutions, demanding Polk specify where American blood had been shed to justify the war, but the House did not consider them.

Peace: the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Frustrated by stalled negotiations, Polk ordered Nicholas Trist to return to Washington, but when Trist received the recall notice in mid-November 1847, he chose to defy the order, deciding to stay and continue negotiations. He wrote a detailed letter to Polk in December to justify his decision. Although Polk was angered by Trist’s insubordination, he decided to give Trist a bit more time to finalize the treaty.

Throughout January 1848, Trist engaged in regular meetings with Mexican officials in Mexico City. At the Mexicans’ request, the treaty signing took place in the small town of Guadalupe Hidalgo, rather than in the capital. Trist negotiated effectively, agreeing to leave Baja California with Mexico but securing the inclusion of the important harbor of San Diego as part of the cession of Alta California. The treaty included the Rio Grande as the southern border of Texas and stipulated a $15 million payment to Mexico. On February 2, 1848, Trist and the Mexican delegation signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Polk received the treaty on February 19 and, after consulting with his Cabinet on February 20, decided to accept it. Rejecting the treaty could have jeopardized continued funding for the war, especially with the House of Representatives now controlled by Whigs. Although Polk was inclined to support more extensive territorial gains, he was wary of Buchanan’s and Walker’s motives, suspecting they were driven by personal ambition rather than national interest.

The treaty faced opposition in the Senate from those who either wanted no Mexican territory or were troubled by the irregular nature of Trist’s negotiations. Polk anxiously awaited the Senate’s decision, hearing mixed reports about its chances of approval. On March 10, the Senate ratified the treaty with a 38-14 vote that crossed partisan and regional lines. The Senate made some modifications to the treaty, which raised concerns about whether Mexico would accept the changes. However, on June 7, Polk received confirmation that Mexico had ratified the treaty.

Polk declared the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo effective as of July 4, 1848, officially ending the war. With this treaty, Polk achieved all four of his major presidential goals, and the territorial acquisitions during his presidency, aside from the 1853 Gadsden Purchase and some later minor adjustments, established the modern borders of the contiguous United States.

Postwar and the territories

Polk was eager to establish a territorial government for Oregon, but the issue became entangled in the contentious debate over slavery. Although few considered Oregon suitable for slavery, the debate persisted. Bills to create a territorial government for Oregon passed the House twice but failed in the Senate. By December, with California and New Mexico under U.S. control, Polk used his annual message to Congress to advocate for the establishment of territorial governments in all three regions.

The Missouri Compromise had previously addressed the extension of slavery within the Louisiana Purchase, prohibiting it north of the 36°30′ latitude. Polk aimed to extend this line into the newly acquired territories, which would have prohibited slavery in Oregon and San Francisco while permitting it in Los Angeles. However, this proposal faced strong opposition in the House from a bipartisan coalition of Northerners. In response, Polk signed a bill in 1848 that established the Territory of Oregon and banned slavery there.

By December 1848, Polk sought to establish territorial governments in California and New Mexico, driven in part by the California Gold Rush’s onset. However, the issue of slavery continued to block progress. This conflict was eventually addressed in the Compromise of 1850.

Polk also had reservations about a bill creating the Department of the Interior, which he signed on March 3, 1849. He was concerned about the federal government’s potential overreach into public lands traditionally managed by the states. Despite his misgivings, he approved the bill.

Other initiatives

Polk’s administration made significant strides in diplomatic and territorial negotiations. Benjamin Alden Bidlack, Polk’s ambassador to the Republic of New Granada, played a key role in negotiating the Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty. While the initial goal was to remove tariffs on American goods, the treaty evolved into a comprehensive agreement that strengthened military and trade relations between the two countries. It also included a U.S.

guarantee of New Granada’s sovereignty over the Isthmus of Panama, which later facilitated the construction of the Panama Canal in the early 20th century. Additionally, the treaty enabled the creation of the Panama Railway, which opened in 1855. This railway, operated by Americans and protected by the U.S. military, provided a faster and safer route between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. The Mallari no–Bidlack Treaty was Washington’s sole 19th-century alliance, establishing a strong American presence in Central America and countering British influence.

In mid-1848, Polk’s administration sought to acquire Cuba, authorizing ambassador Romulus Mitchell Saunders to offer Spain up to $100 million for the territory—a substantial sum equivalent to $3.52 billion today. Although Cuba was attractive to Southerners due to its proximity and existing slavery, Spain rejected the offer as it continued to profit from Cuban resources such as sugar, molasses, rum, and tobacco. Despite Polk’s interest in acquiring Cuba, he did not support the filibuster expedition led by Narciso López, who aimed to invade and annex the island.

Domestic policy

Fiscal policy

In his inaugural address, President James K. Polk advocated for the re-establishment of the Independent Treasury System, a framework that kept government funds directly in the Treasury rather than in private banks. This system, initially established by President Martin Van Buren, had been dismantled during John Tyler’s presidency. Polk’s strong opposition to a national bank was evident in his address and his first annual message to Congress in December 1845, where he emphasized the need for the government to manage its own funds.

Despite initial resistance, Congress eventually passed the Independent Treasury Act. The House approved the bill in April 1846, and the Senate followed in August, with neither chamber receiving a single Whig vote. Polk signed the act into law on August 6, 1846. The law mandated that public revenues be held in the Treasury and sub-treasuries located in various cities, separate from private or state banks. This system remained in place until the Federal Reserve Act was enacted in 1913.

Another significant domestic initiative during Polk’s presidency was the reduction of tariffs. Polk tasked Secretary of the Treasury Robert Walker with drafting a lower tariff bill. The Walker Tariff, which Polk submitted to Congress, faced intense lobbying from both sides. The House passed it, and the Senate approved it in July 1846 after a close vote that required Vice President George M. Dallas to cast the deciding vote.

Although Dallas was from protectionist Pennsylvania, he supported the bill, recognizing that aligning with the administration was beneficial for his political future. The Walker Tariff significantly lowered rates compared to the Tariff of 1842, leading to a surge in Anglo-American trade following both the tariff reduction in the U.S. and the repeal of the Corn Laws in Great Britain.

Development of the country

In 1846, President James K. Polk vetoed the Rivers and Harbors Bill, which aimed to allocate $500,000 for improving port facilities. Polk rejected the bill on the grounds that it was unconstitutional and favored specific areas unfairly, including ports without significant foreign trade. He believed that internal improvements were the responsibility of the states and that such federal spending could lead to corruption and unhealthy competition among legislators for district favors. This stance mirrored his hero Andrew Jackson, who had vetoed the Maysville Road Bill in 1830 for similar reasons.

Polk’s opposition to federal funding for internal improvements was firm throughout his presidency. He pocket-vetoed another internal improvements bill in 1847 and issued a full veto message against it when Congress reconvened in December. Although similar bills continued to be proposed in 1848, none reached his desk. On March 3, 1849, the final day of his presidency, Polk prepared a draft veto message in anticipation of a potential internal improvements bill, but it was unnecessary as no such bill passed.

During Polk’s final days in office, the discovery of gold in California was announced. This news, which arrived after the 1848 election, validated Polk’s expansionist policies. Despite earlier skepticism from his political opponents, Polk’s enthusiasm for the gold discovery was evident in his final annual message to Congress and a special message confirming the gold findings. This news significantly contributed to the California Gold Rush, leading to a mass migration to the state.

Regarding judicial appointments, Polk appointed two justices to the U.S. Supreme Court:

- Levi Woodbury (Seat 2) – Appointed on September 20, 1845, and served until September 4, 1851. Woodbury was a recess appointment following the death of Justice Joseph Story, and he was confirmed when the Senate reconvened.

- Robert Cooper Grier (Seat 3) – Appointed on August 4, 1846, and served until January 31, 1870. Grier is notable for his opinion in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case, where he declared that slaves were property and could not sue.

Polk also appointed eight other federal judges to various courts, including one to the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia and seven to United States district courts.

Election of 1848

Honoring his pledge to serve only one term, James K. Polk chose not to seek re-election in 1848. At the Democratic National Convention, Lewis Cass was nominated as the party’s candidate. The Whig National Convention nominated Zachary Taylor for president and Millard Fillmore for vice president. Polk was particularly surprised and disappointed by Martin Van Buren’s shift to lead a breakaway Free Soil party, which advocated for abolition and was seen as a threat to national unity.

During the election campaign, Polk refrained from actively supporting Cass, staying at the White House and removing some of Van Buren’s supporters from federal positions. Taylor won the election with a plurality of the popular vote and a majority of the electoral votes, much to Polk’s disappointment. Polk had a low opinion of Taylor, viewing him as lacking judgment and having little on important public issues.

Despite his personal feelings, Polk observed tradition by welcoming President-elect Taylor to Washington and hosting him at a White House dinner. On March 3, 1849, Polk left the White House, having completed his final tasks and leaving behind a clean desk. He worked from his hotel or the Capitol on last-minute appointments and bill signings until his departure. He attended Taylor’s inauguration on March 5, 1849, which was postponed from the traditional March 4 due to it falling on a Sunday. Although unimpressed with Taylor, Polk wished him well as he left office.

Post-presidency and death (1849)

James K. Polk’s time in the White House took a toll on his health. While he entered office full of enthusiasm and vigor, by the end of his presidency, he was exhausted from years of intense public service. After leaving Washington on March 6, 1849, for a planned triumphal tour of the Southern United States, Polk was in poor health. The tour, intended to end in Nashville, included a visit to a house he had purchased in advance, later known as Polk Place, which had once belonged to his mentor, Felix Grundy.

As Polk and his wife, Sarah, traveled down the Atlantic coast and through the Deep South, they received enthusiastic receptions and were frequently banqueted. By the time they reached Alabama, Polk had developed a bad cold and was concerned about reports of cholera. Despite these worries and a death from cholera on his riverboat, the Polks continued their journey due to Louisiana’s overwhelming hospitality.

Polk fell ill again while traveling up the Mississippi, where he spent four days ashore in a hotel. Though a doctor assured him he did not have cholera, he remained unwell until arriving in Nashville on April 2, 1849, to a grand reception.

Settling into Polk Place, the former president initially seemed to recover. However, in early June, he fell gravely ill again, likely from cholera. Surrounded by doctors, he lingered for several days and chose to be baptized into the Methodist Church, despite the presence of his mother’s Presbyterian clergyman and his own wife’s Presbyterian beliefs. Polk passed away on June 15, 1849, at age 53. According to traditional accounts, his last words were, “I love you, Sarah, for all eternity, I love you.” Though the exactness of these words is uncertain, they reflect the deep affection he had for his wife. James K. Polk

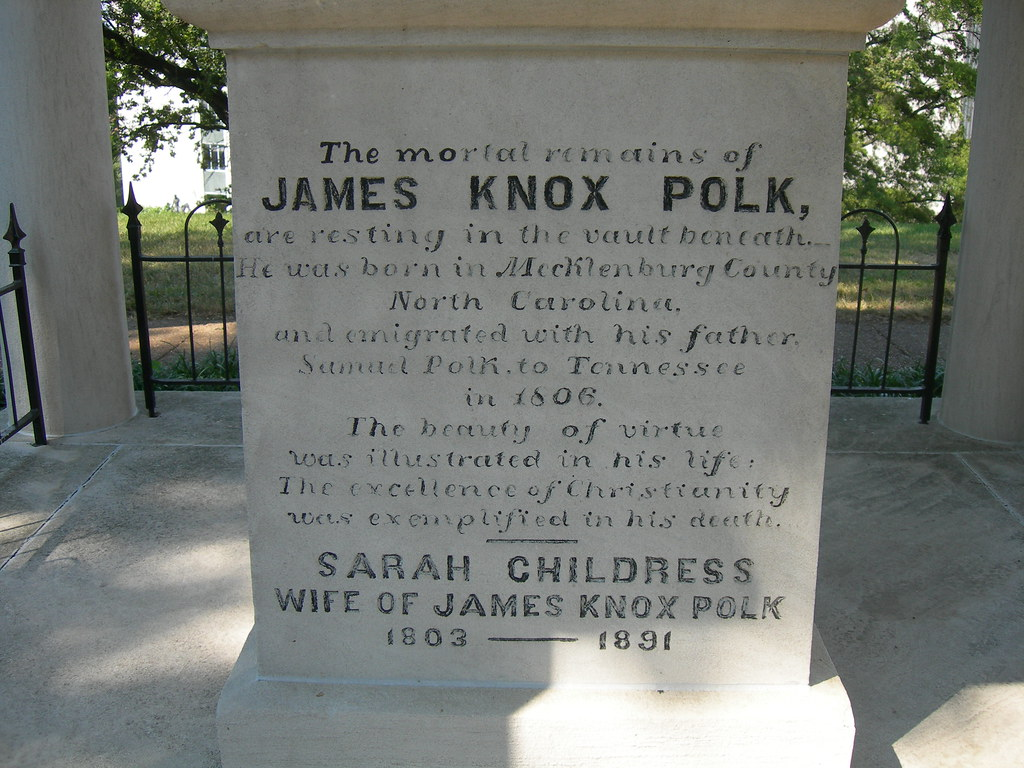

Polk’s funeral was held at McKendree Methodist Church in Nashville. Sarah Polk lived at Polk Place for 42 years after his death, passing away on August 14, 1891, at the age of 87. Polk Place was eventually demolished in 1901.

Burials

James K. Polk’s remains have been moved twice since his death. Initially, he was buried in Nashville City Cemetery due to regulations related to his death from an infectious disease. In 1850, Polk’s body was relocated to a tomb on the grounds of Polk Place, in accordance with his will.

In 1893, both James and Sarah Polk’s remains were moved to their current resting place on the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol in Nashville. This location became their final resting place for many years.

In March 2017, the Tennessee Senate approved a resolution that could potentially lead to relocating the Polks’ remains to their family home in Columbia. James K. Polk This move would require approval from state lawmakers, the courts, and the Tennessee Historical Commission. A year later, a renewed attempt to reinter Polk was initially defeated but was later reconsidered and approved. Governor Bill Haslam did not sign the bill into law, which allowed the plan to proceed.

The issue continued to be contentious, with the Tennessee Capitol Commission holding hearings on the matter in November 2018. The Tennessee Historical Commission reiterated its opposition to James K. Polk moving the tomb, leading to a delay in the vote and leaving the future of the Polks’ remains uncertain.

Legacy and historical view

- Early Criticism and Recognition: Polk was not widely discussed in depth until after his death. His early biographers and historians were few, and significant evaluations of his presidency only began to emerge in the 20th century. Eugene I. McCormac’s 1922 biography was among the first to provide a comprehensive view of Polk’s presidency, relying heavily on his presidential diary.

- Rankings and Assessments: Polk’s ranking among U.S. presidents has varied. He was ranked tenth in Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr.’s 1948 poll, eighth in Schlesinger’s 1962 poll, ninth in Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.’s 1996 poll, and fourteenth in C-SPAN’s 2017 survey. These rankings reflect a complex view of Polk as both an effective and controversial president.

- Successes and Achievements: Polk is widely seen as a successful president, particularly noted for his effective use of presidential power. Historian John C. Pinheiro argued that Polk achieved nearly all of his presidential goals, including the acquisition of Oregon Territory, California, James K. Polk and New Mexico, the resolution of the Texas border dispute, the establishment of a new federal depository system, and the reduction of tariffs. Polk’s diligent work and clear convictions earned him high praise from historians like Robert W. Merry and Paul H. Bergeron.

- Criticisms and Legacy Concerns: Despite his achievements, Polk’s presidency is also criticized for not anticipating the sectional conflicts that would lead to the Civil War. Critics like David M. Pletcher and Fred I. Greenstein have pointed out that Polk’s expansionist policies and failure to address the issues of slavery in the newly acquired territories contributed to the growing sectional tensions. William Dusenberry noted that Polk’s personal involvement in slavery influenced his policies and decisions.

- Impact on Later Conflicts: Polk’s Mexican-American War and its outcomes played a significant role in shaping future American military and political landscapes. James K. Polk The conflict served as a training ground for future leaders of the Civil War, such as Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee.

Overall, Polk’s presidency is remembered for its ambitious expansionist agenda and significant achievements in shaping the United States, but also for its role in setting the stage for the sectional conflicts that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

Polk and slavery

James K. Polk’s involvement with slavery and his views on the institution were significant aspects of his life and presidency. Here is a detailed account of his relationship with slavery:

Ownership and Management of Enslaved People:

- Inheritance and Early Ownership: Polk inherited twenty enslaved individuals from his family and purchased additional slaves throughout his life. By 1831, he was managing plantations in Tennessee and Mississippi, using enslaved people to work the land. His plantation near Coffeeville, Mississippi, was particularly productive, benefiting from richer soil compared to his previous property in Somerville, Tennessee.

- Plantation Management: Polk managed his plantations largely from a distance, only occasionally visiting. He expanded his slaveholdings in the 1840s to ensure a comfortable retirement after his presidency. Despite his absentee management, he was involved in purchasing slaves and reinvesting plantation earnings in new slaves.

- Discipline and Treatment: The treatment of slaves on Polk’s plantations varied over time. Initially, overseers employed by Polk were reportedly harsh, particularly one named Ephraim Beanland. Later, a more balanced approach was adopted, with some overseers being more lenient. However, discipline remained strict, and reports of mistreatment were not uncommon.

Political and Personal Views on Slavery:

- Political Context: Polk’s views on slavery were shaped by his Southern background and political ideology. He believed in the protection of Southern rights, including the right to hold slaves, and opposed efforts like the Wilmot Proviso, which sought to ban slavery in new territories acquired from Mexico.

- Slavery and Expansion: Polk’s support for territorial expansion, including the annexation of Texas and the war with Mexico, was partly driven by a belief in extending the reach of slavery. This expansion was controversial and seen by many as a means to enhance the influence of slaveholding interests in the United States.

- Legacy and Criticism: Polk faced criticism from abolitionists and political opponents who viewed his expansionist policies as a means to extend the reach of slavery. While he was focused on achieving his territorial and economic goals, the consequences of his actions contributed to the growing sectional tensions that would lead to the Civil War.

Post-Presidency and Slavery:

- Will and Freed Slaves: Polk’s will included a nonbinding expectation that his slaves would be freed after both he and his wife had passed away. However, slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, before Polk’s death. Sarah Polk’s sale of a half-interest in her slaves in 1860 made it unlikely that the slaves would have been freed if she had died before the abolition of slavery.

- Historical Reflection: Polk’s legacy regarding slavery is complex. While he is recognized for his significant achievements in expanding the United States, his role in perpetuating slavery and his failure to address its divisive impact on the nation are also critical aspects of his historical evaluation.

Overall, Polk’s presidency and personal actions regarding slavery reflect the broader historical context of the period and contribute to the ongoing evaluation of his impact on American history.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_K._Polk