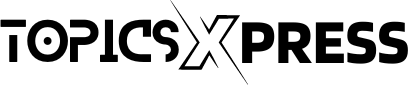

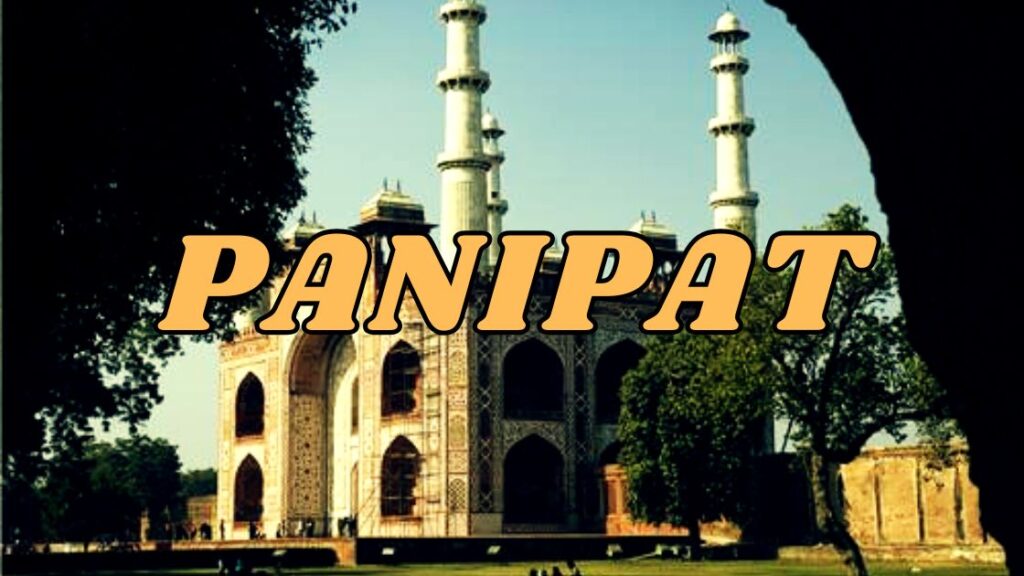

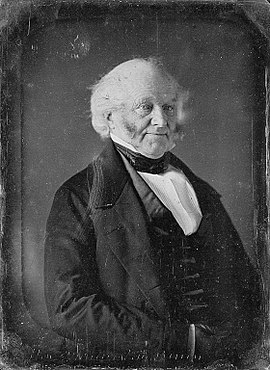

Martin Van Buren, born on December 5, 1782, in Kinderhook, New York, was an American lawyer, diplomat, and statesman. He served as the eighth President of the United States from 1837 to 1841 and played a foundational role in establishing the Democratic Party. Beginning his political career in the Democratic-Republican Party, Van Buren held various significant positions including New York’s attorney general, U.S. senator, and briefly, the governor of New York. He joined Andrew Jackson’s administration as Secretary of State and later Vice President, winning the presidency in 1836 after Jackson’s endorsement.

Van Buren’s presidency was marked by his response to the Panic of 1837, advocating for an Independent Treasury system to stabilize the economy. Despite early successes, economic challenges and political opposition led to his defeat in the 1840 election to William Henry Harrison. He continued to influence national politics as an anti-slavery leader, notably as the Free Soil Party’s presidential candidate in 1848.

Van Buren’s legacy includes his pivotal role in shaping the Democratic Party’s organizational structure and his enduring impact on American political thought. He died on July 24, 1862, in Kinderhook, leaving behind a complex legacy of economic policies and anti-slavery advocacy.

Martin Van Buren was the eighth President of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. He was a key figure in the development of the Democratic Party and served as Andrew Jackson’s Vice President before becoming President himself. Van Buren faced economic challenges during his presidency, including the Panic of 1837, which led to a severe economic depression. He was known for his skill in political organization and diplomacy, earning the nickname “The Little Magician” for his political acumen. After his presidency, he remained active in politics and played a role in shaping the Democratic Party’s policies.

Early Life and Education Martin Van Buren

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

Early Years in Kinderhook

Martin Van Buren was born on December 5, 1782, in Kinderhook, New York, situated in the Hudson River Valley, about 20 miles south of Albany. His father, Abraham Van Buren, traced his ancestry to Cornelis Maessen from Buurmalsen, Netherlands, who arrived in New Netherland in 1631. Unlike his predecessors, Van Buren was not of British descent but entirely of Dutch heritage, marking a unique distinction among U.S. presidents.

Abraham Van Buren, a Patriot during the American Revolution, later aligned with the Democratic-Republican Party. He owned and operated an inn and tavern in Kinderhook, serving as the town clerk. Martin Van Buren was the third of five children born to Abraham and Maria Hoes Van Alen, who was previously married and had three children.

Van Buren received his early education at the village schoolhouse, where he learned Dutch as his primary language before mastering English. His formal education included studies in Latin at the Kinderhook Academy and later at Washington Seminary in Claverack. He began his legal studies in 1796 under the mentorship of Peter Silvester and his son Francis, ending his formal education upon his admission to the New York bar in 1803.

Known for his small stature at 5 feet 6 inches, Van Buren was affectionately nicknamed “Little Van.” He started his legal career wearing humble clothing, which prompted advice from the Silvesters to improve his appearance. This guidance influenced his polished demeanor and meticulous appearance throughout his career as a lawyer and politician.

In 1807, Van Buren married his childhood sweetheart, Hannah Hoes, in Catskill, New York. Raised in a Dutch-speaking household in Valatie, Hannah spoke English with a noticeable accent. The couple had six children, with four surviving to adulthood. Tragically, Hannah passed away in 1819 from tuberculosis, and Van Buren never remarried.

Martin Van Buren’s early life and education in Kinderhook laid the foundation for his future as a lawyer, politician, and influential figure in American history.

Education and Legal Career

Van Buren’s formal education continued at the Kinderhook Academy, where he received further academic instruction. His interest in law emerged during this time, prompting him to study under local attorneys to prepare for his legal career. After diligent study and apprenticeship, he was admitted to the New York bar in 1803, marking the beginning of his distinguished career in law and subsequent entry into politics.

Early Political Career

Establishing a Legal and Political Base

Upon returning to Kinderhook in 1803, Martin Van Buren entered into a law partnership with his half-brother, James Van Alen. This partnership provided financial stability, enabling Van Buren to deepen his involvement in politics, a passion he had pursued since the age of 18. His early political activities included attending a Democratic-Republican Party convention in Troy, New York, where he successfully secured John Peter Van Ness’s nomination for a congressional seat.

Political Alliances and Career Advancement

Van Buren’s political trajectory evolved as he aligned with influential figures like DeWitt Clinton and Daniel D. Tompkins, breaking away from his earlier association with Aaron Burr’s faction. Following the success of Clinton and Tompkins in the 1807 elections, Van Buren was appointed as Surrogate of Columbia County, New York. Seeking broader opportunities for his legal and political career, Van Buren relocated his family to Hudson, the county seat of Columbia County, in 1808.

Rising Influence and War Efforts

In 1812, Van Buren secured the Democratic-Republican nomination for a seat in the New York State Senate despite opposition from both Democratic-Republicans and Federalists aligned with John Peter Van Ness. His tenure coincided with the onset of the War of 1812, during which he collaborated with Clinton, Governor Tompkins, and others to support President James Madison’s administration. Van Buren’s role extended to serving as a judge advocate during William Hull’s court-martial after the surrender of Detroit.

Election to State Office

Van Buren’s steadfast support for the war efforts bolstered his reputation, leading to his election as New York Attorney General in 1815. He subsequently moved to Albany, the state capital, where he formed a legal partnership and maintained a residence with political ally Roger Skinner. Re-elected to the state senate in 1816, Van Buren continued to serve simultaneously as both state senator and attorney general, further solidifying his position in New York State politics.

Legal Contributions and Public Service

In 1819, Van Buren played a pivotal role in prosecuting the perpetrators of New York’s first murder-for-hire case, demonstrating his commitment to justice and public service amidst his burgeoning political career.

Albany Regency

Formation and Influence

The Albany Regency, established by Martin Van Buren and his political allies in the early 19th century, wielded significant influence in New York State politics. Emerging from the Democratic-Republican Party, the Regency operated as a tightly knit political machine centered in Albany, the state capital. Its founding members included Van Buren, Governor DeWitt Clinton, and other key figures who sought to consolidate power and advance Democratic-Republican principles.

Political Strategy and Organization

Under Van Buren’s strategic leadership, the Albany Regency pioneered modern political tactics, including voter mobilization, patronage appointments, and legislative coordination. These efforts aimed to secure electoral victories and implement policy agendas favorable to their party. The Regency’s meticulous organization and disciplined approach to politics set a precedent for political machines across the United States.

Legacy and Impact

The Albany Regency’s legacy extended beyond New York State, influencing national politics and shaping the Democratic Party’s organizational structure. Its methods of political organization and coalition-building became models for subsequent political movements, highlighting Van Buren’s skill as a political organizer and his lasting impact on American political history.

Entry into National Politics

Emergence on the National Stage

Martin Van Buren’s entry into national politics was marked by his strategic acumen and growing influence within the Democratic-Republican Party. Building on his successes in New York State politics, Van Buren’s reputation as a skilled political organizer and advocate for states’ rights caught the attention of national leaders.

Rise to Prominence

Van Buren’s pivotal moment came during the presidency of Andrew Jackson, whom he supported ardently. Recognizing Van Buren’s organizational talents, Jackson appointed him as Secretary of State in 1829. In this role, Van Buren played a crucial part in shaping Jacksonian policies and strengthening the Democratic Party’s cohesion.

National Leadership

Van Buren’s tenure as Secretary of State marked his transition to a national political figure. His diplomatic skills and commitment to Jackson’s vision solidified his position within the administration and positioned him as a key strategist for the Democratic Party.

Impact and Influence

Van Buren’s early forays into national politics laid the groundwork for his subsequent presidential ambitions and his role in shaping American political discourse. His ability to navigate complex political landscapes and forge alliances proved instrumental in his ascent to national leadership, setting the stage for his future impact on the presidency and American political history.

Entry into National Politics: 1828 Elections

Strategic Involvement

Martin Van Buren’s entry into national politics escalated significantly during the pivotal 1828 elections. Already a prominent figure in New York politics and a skilled organizer within the Democratic-Republican Party, Van Buren capitalized on his influence to support Andrew Jackson’s presidential campaign. Recognizing Jackson’s appeal to the common man and his alignment with states’ rights principles, Van Buren strategically positioned himself as a crucial ally.

Architect of Victory

Van Buren’s role as a key architect of Jackson’s victory cannot be overstated. He orchestrated a robust campaign strategy, mobilizing grassroots support and leveraging his political network to secure electoral votes. Van Buren’s efforts were instrumental in navigating the complexities of a divisive election characterized by fierce opposition from the incumbent President John Quincy Adams and his supporters.

Formation of Democratic Party

The success of Jackson’s campaign marked a turning point in American politics. Van Buren’s organizational skills and commitment to Jackson’s populist agenda laid the foundation for the formation of the modern Democratic Party. As Jackson’s influence grew, so did Van Buren’s national stature, positioning him as a central figure in shaping the party’s policies and electoral strategies.

Legacy and Influence

The 1828 elections catapulted Martin Van Buren onto the national stage, setting the stage for his subsequent roles as Secretary of State and Vice President. His strategic contributions to Jackson’s victory cemented his reputation as a masterful political strategist and laid the groundwork for his own presidential ambitions. Van Buren’s legacy as a pivotal figure in American political history is underscored by his role in transforming the Democratic Party and shaping the course of 19th-century politics.

Jackson Administration (1829–1837): Secretary of State

Appointment and Responsibilities

Martin Van Buren’s tenure as Secretary of State under President Andrew Jackson from 1829 to 1831 marked a critical phase in his political career. Appointed for his strategic acumen and loyalty to Jackson, Van Buren played a pivotal role in shaping the administration’s foreign policy and domestic agenda.

Diplomatic Initiatives

As Secretary of State, Van Buren focused on expanding American influence in international affairs while advancing Jackson’s vision of democratic governance. He navigated delicate diplomatic relations with European powers and Latin American nations, advocating for policies that aligned with Jacksonian principles of sovereignty and non-intervention.

Domestic Political Strategies

Beyond foreign affairs, Van Buren leveraged his position to consolidate support for Jackson’s domestic policies, including the dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States and the implementation of policies favoring states’ rights and economic populism. His strategic insights and organizational skills were instrumental in navigating the political landscape and advancing Jackson’s agenda through Congress.

Legacy and Impact

Van Buren’s tenure as Secretary of State solidified his reputation as a key architect of Jacksonian democracy. His diplomatic achievements and political maneuvering laid the groundwork for his subsequent rise to the vice presidency and ultimately the presidency. Van Buren’s contributions during the Jackson administration underscored his role as a central figure in shaping American foreign policy and domestic politics during the early 19th century.

Ambassador to Britain and Vice Presidency

Diplomatic Service in Britain

After serving as Secretary of State, Martin Van Buren was appointed as the United States Ambassador to Great Britain by President Andrew Jackson. From 1831 to 1832, Van Buren navigated delicate diplomatic relations, representing American interests with finesse and contributing to the strengthening of bilateral ties between the two nations.

Election as Vice President

Van Buren’s diplomatic success positioned him favorably within the Democratic Party. In 1832, with Andrew Jackson’s strong endorsement, Van Buren was nominated as the vice-presidential candidate. He won the election alongside Jackson, becoming the eighth Vice President of the United States from 1833 to 1837.

Influence and Policy Contributions

As Vice President, Van Buren continued to advocate for Jackson’s policies, including the dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States and the promotion of states’ rights. His tenure was marked by his strategic alignment with Jackson’s populist agenda and his efforts to maintain party unity amidst growing political divisions.

Path to the Presidency

Van Buren’s diplomatic skills and political astuteness during his tenure as Ambassador to Britain and Vice President paved the way for his own presidential aspirations. His experiences in international diplomacy and domestic politics prepared him for the challenges of national leadership, culminating in his election as the eighth President of the United States in 1836.

Ambassador to Britain and Vice Presidency

In August 1831, President Jackson appointed Martin Van Buren as Ambassador to Britain during a congressional recess, and Van Buren assumed his duties in London the following month. His reception in London was warm, but in February 1832, shortly after turning 49, Van Buren received news that the Senate had rejected his nomination. The rejection was orchestrated primarily by John C. Calhoun, who saw it as a move to end Van Buren’s political career. Calhoun’s maneuver, however, backfired painting Van Buren as a victim of political maneuvering only bolstered his standing in Jackson’s eyes and among Democratic Party faithfuls.

Calhoun’s miscalculation fueled Van Buren’s candidacy for vice president, supported by Jackson’s efforts to ensure Van Buren’s nomination at the Democratic National Convention in May 1832. Despite opposition from Calhoun’s allies, Van Buren secured the vice-presidential nomination due to Jackson’s backing and the influential Albany Regency. Returning from Europe in July 1832, Van Buren quickly became embroiled in the Bank War, siding with Jackson against renewing the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, which he viewed as a relic of Alexander Hamilton’s economic policies.

In the 1832 presidential election, Henry Clay made the bank issue central, but Jackson and Van Buren overwhelmingly won re-election. Van Buren took office as Vice President on March 4, 1833, at the age of 50. During the Nullification Crisis, he advised Jackson on conciliatory measures with South Carolina, playing a supportive role in diffusing tensions over the Tariff of 1833.

As Vice President, Van Buren remained a key advisor to Jackson, accompanying him on tours and supporting Jackson’s efforts to remove federal deposits from the Second Bank despite initial congressional resistance. Van Buren also worked to undermine potential political rivals, including Daniel Webster, to solidify Jacksonian policies over personal allegiances.

By Jackson’s second term, supporters coalesced into the Democratic Party, while opponents formed the Whig Party, marking a significant shift in American political alignment.

Diplomatic Service in Britain

After serving as Secretary of State, Martin Van Buren was appointed as the United States Ambassador to Great Britain by President Andrew Jackson. From 1831 to 1832, Van Buren navigated delicate diplomatic relations, representing American interests with finesse and contributing to the strengthening of bilateral ties between the two nations.

Election as Vice President

Van Buren’s diplomatic success positioned him favorably within the Democratic Party. In 1832, with Andrew Jackson’s strong endorsement, Van Buren was nominated as the vice presidential candidate. He won the election alongside Jackson, becoming the eighth Vice President of the United States from 1833 to 1837.

Influence and Policy Contributions

As Vice President, Van Buren continued to advocate for Jackson’s policies, including the dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States and the promotion of states’ rights. His tenure was marked by his strategic alignment with Jackson’s populist agenda and his efforts to maintain party unity amidst growing political divisions.

Path to the Presidency

Van Buren’s diplomatic skills and political astuteness during his tenure as Ambassador to Britain and Vice President paved the way for his own presidential aspirations. His experiences in international diplomacy and domestic politics prepared him for the challenges of national leadership, culminating in his election as the eighth President of the United States in 1836.

Presidential election of 1836

The presidential election of 1836 was a pivotal moment in American political history, marked by Martin Van Buren’s successful bid for the presidency following Andrew Jackson’s two terms in office. Here’s a concise overview:

In the lead-up to the 1836 presidential election, Andrew Jackson, despite declining to seek another term, remained a formidable figure within the Democratic Party. Jackson’s endorsement was crucial in propelling Martin Van Buren to the party’s presidential nomination at the 1835 Democratic National Convention, where Van Buren faced no opposition. However, the selection of a vice-presidential candidate was more contentious, with Southern Democrats favoring William Cabell Rives over Jackson’s preference, Richard M. Johnson. Jackson’s influence ultimately secured Johnson’s nomination, highlighting his enduring sway within the party despite stepping down from office.

Van Buren’s main challengers in the election were Whig Party candidates who lacked unity and a cohesive platform. Hugh Lawson White, Daniel Webster, and William Henry Harrison each represented different regional interests within the Whig coalition, aiming to prevent Van Buren from securing a majority of the electoral votes and forcing the election to the House of Representatives. The Whigs criticized Jacksonian policies, particularly regarding the national bank and allegations of executive overreach, while attempting to exploit sectional tensions and associating Democrats with abolitionism.

Southern concerns over a Northern president posed a significant challenge to Van Buren’s candidacy, prompting him to reassure Southern voters of his commitment to maintaining slavery where it existed and opposing abolitionism. Van Buren’s electoral strategy included supporting legislation to restrict abolitionist mail in Southern states, despite his personal belief that slavery was morally wrong but constitutionally protected.

The election results in 1836 saw Van Buren secure victory with 170 electoral votes and 50.9% of the popular vote, while Harrison led the Whigs with 73 electoral votes. Despite the Whigs’ strategic efforts, Van Buren’s success was attributed to his political acumen, Jackson’s backing, and the Democratic Party’s organizational strength. The election marked a pivotal moment in American politics, solidifying the emergence of the Second Party System, where Democrats and Whigs became the dominant political forces, setting the stage for future political alignments and disputes.

Election Dynamics

In 1836, the Democratic Party nominated Martin Van Buren as their presidential candidate, largely due to his close association with President Andrew Jackson and his role as Vice President. The election took place against a backdrop of economic uncertainty and sectional tensions, with the Whig Party emerging as the primary opposition.

Campaign Issues

Van Buren campaigned on a platform that emphasized continuing Jacksonian policies, including opposition to the Second Bank of the United States and support for states’ rights. The campaign also addressed economic issues, such as the aftermath of the Panic of 1837 and concerns over westward expansion and slavery.

Results

Van Buren’s candidacy was bolstered by Jackson’s popularity and the organizational strength of the Democratic Party, particularly the Albany Regency. He faced off against multiple Whig candidates, including William Henry Harrison, Hugh Lawson White, and others, each representing different regional and ideological factions within the Whig Party.

Outcome

Martin Van Buren won the election of 1836, becoming the eighth President of the United States. His victory reflected the Democratic Party’s dominance during the Jacksonian era and solidified his place as a key figure in shaping 19th-century American politics.

Legacy

Van Buren’s presidency marked a continuation of Jacksonian principles, but his tenure was soon tested by economic challenges, including the severe Panic of 1837. Despite his efforts to address these issues, his presidency faced criticism and paved the way for shifting political landscapes leading into subsequent elections.

Presidency (1837–1841)

Martin Van Buren’s presidency from 1837 to 1841 was shaped by economic challenges, political divisions, and his efforts to uphold Jacksonian principles while navigating a changing national landscape.

Cabinet

Martin Van Buren’s cabinet, formed at the outset of his presidency in 1837, reflected a strategic mix of continuity from Andrew Jackson’s administration and regional representation aimed at fostering Democratic unity.

Van Buren retained many of Jackson’s cabinet appointees, a decision intended to bolster Democratic cohesion and dampen Whig momentum in the South. The composition of his cabinet spanned various regions: Levi Woodbury from New England as Secretary of the Treasury, Benjamin Franklin Butler representing New York as Attorney General, Mahlon Dickerson from New Jersey as Secretary of the Navy, John Forsyth of Georgia as Secretary of State, and Amos Kendall of Kentucky overseeing the Post Office, representing the West.

The position of Secretary of War, initially offered to William Cabell Rives who declined, was ultimately filled by Joel Roberts Poinsett of South Carolina. This selection underscored Van Buren’s effort to include viewpoints from states pivotal during the Nullification Crisis, despite some criticism from Pennsylvanians and Democratic factions advocating for broader patronage distribution.

Van Buren conducted formal cabinet meetings, departing from Jackson’s informal advisory gatherings. He encouraged robust discussions among his advisors, positioning himself as a mediator and final decision-maker amidst differing opinions. This approach ensured that each department head had a voice while maintaining presidential prerogative. Van Buren personally engaged in matters of foreign affairs and the Treasury, while allowing significant autonomy to the War, Navy, and Post Office departments under their respective secretaries.

Overall, Van Buren’s cabinet strategy aimed to sustain Jacksonian policies while navigating political challenges, emphasizing unity within the Democratic Party and administrative cohesion across diverse national interests.

Economic Challenges: Van Buren inherited a turbulent economic situation upon assuming office. The country was reeling from the aftermath of the Panic of 1837, triggered by a financial crisis that led to widespread bank failures, unemployment, and economic downturn. Van Buren’s response to the crisis was shaped by his distrust of banks and his commitment to fiscal conservatism. He advocated for the establishment of an Independent Treasury system, which aimed to remove federal funds from private banks and store them in government vaults to stabilize the economy.

Political Divisions and Opposition: Van Buren faced significant political opposition during his presidency. The Whig Party, now more organized under Henry Clay’s leadership, criticized his handling of the economic crisis and accused him of failing to address the nation’s financial woes effectively. Whigs in Congress obstructed many of Van Buren’s legislative initiatives, complicating his ability to implement his policy agenda.

Foreign Policy and Expansion: In foreign affairs, Van Buren focused on maintaining diplomatic relations and expanding U.S. influence. He navigated tensions with Britain over trade issues and sought to solidify American interests in the Western Hemisphere. Van Buren supported diplomatic efforts to resolve border disputes with Canada and Mexico, contributing to a relatively stable period in U.S. foreign relations during his presidency.

Legacy and Historical Assessment: Van Buren’s presidency is often evaluated in the context of his handling of the economic crisis and his efforts to maintain Jacksonian policies amidst political opposition. While his Independent Treasury system laid the groundwork for future financial reforms, his inability to effectively address the economic downturn contributed to his defeat in the 1840 election. Historians generally view Van Buren as a competent administrator and dedicated public servant who navigated complex challenges during a transformative period in American history.

Panic of 1837

Martin Van Buren faced a significant economic crisis soon after taking office, known as the Panic of 1837, which profoundly impacted his presidency and political landscape.

The panic originated when several key state banks in New York suspended the conversion of paper money into gold or silver in May 1837, triggering a nationwide financial collapse. This crisis led to a five-year depression marked by widespread bank failures and soaring unemployment rates.

Van Buren attributed the economic turmoil to both domestic and international financial speculation and the excessive lending practices of U.S. banks. His opponents, particularly the Whigs in Congress, blamed Andrew Jackson’s policies, including the 1836 Specie Circular, which required payment for public lands in hard currency.

Despite pressure to repeal the Specie Circular, Van Buren hesitated under Jackson’s advice, believing the policy needed time to stabilize the economy. However, the prolonged economic downturn bolstered Whig gains in the 1838 elections, both at the state and federal levels.

In response to the crisis, Van Buren proposed an Independent Treasury system to safeguard federal funds with gold or silver, detached from private banks. This proposal aimed to stabilize the nation’s monetary system and prevent inflation. Although initially opposed by conservative Democrats and Whigs, the plan eventually became law in 1840, reflecting Van Buren’s determination to assert federal control over financial policy.

Despite these efforts, the economic downturn continued to dominate Van Buren’s presidency and became a focal point of his re-election campaign in 1840. The Whigs, capitalizing on public dissatisfaction, would ultimately repeal the Independent Treasury system in 1841, but its principles endured until the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913.

Van Buren’s handling of the Panic of 1837 and his economic policies would shape both his legacy and the course of American financial policy for decades to come.

Indian removal

During Martin Van Buren’s presidency, federal policies regarding Native American tribes were marked by the continuation and enforcement of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, a legacy of his predecessor, Andrew Jackson. This policy aimed to relocate Indian tribes west of the Mississippi River to make way for white settlement.

Under Van Buren’s administration, the federal government negotiated 19 treaties with various Indian tribes. One of the most infamous instances was the 1835 Treaty of New Echota with the Cherokee tribe. This treaty, signed by some Cherokee representatives but not endorsed by the majority, stipulated the surrender of Cherokee lands in the southeastern United States in exchange for territory in present-day Oklahoma. When many Cherokees resisted relocation, Van Buren authorized General Winfield Scott to forcibly remove them in 1838.

The Cherokee removal, known as the Trail of Tears, was a tragic episode in American history. Cherokee people were initially gathered in harsh internment camps during the summer of 1838. Due to logistical challenges such as extreme heat and drought, the actual forced migration was delayed until the fall, when around 20,000 Cherokees were compelled to relocate westward against their will.

Van Buren’s administration also confronted the Second Seminole War in Florida, where Seminole Indians resisted removal. The conflict escalated in late 1837 with a major offensive by the U.S. Army, including the Battle of Lake Okeechobee. Recognizing the difficulty of completely removing the Seminoles from Florida, Van Buren’s administration eventually negotiated a compromise allowing some Seminoles to remain in southwest Florida.

These actions underscored the federal government’s aggressive policies towards Native American tribes during Van Buren’s presidency, leading to profound and enduring consequences for Native peoples and their lands.

Texas

During Martin Van Buren’s presidency, the issue of Texas became increasingly significant, setting the stage for future conflicts and debates over expansion and slavery.

Texas had become an independent republic in 1836 after breaking away from Mexico. Throughout Van Buren’s tenure, Texas sought annexation into the United States, which raised complex political and sectional issues. Annexation was highly contentious due to concerns over the expansion of slavery into new territories, which could upset the delicate balance between free and slave states in Congress.

Van Buren approached the issue cautiously. His administration recognized the Republic of Texas diplomatically but refrained from initiating formal annexation proceedings. The primary concerns were maintaining peaceful relations with Mexico, which still claimed Texas as part of its territory, and managing the growing sectional tensions over slavery expansion.

The annexation of Texas was a major campaign issue in the presidential election of 1844, following Van Buren’s presidency. The Democratic candidate, James K. Polk, supported annexation as part of his platform, ultimately winning the election and leading to Texas joining the Union in 1845 during Polk’s presidency.

Van Buren’s cautious approach to Texas reflected his efforts to navigate the complexities of American expansionism and slavery politics during a turbulent period in U.S. history.

Border Violence with Canada

Caroline Episode

The Caroline affair of 1837 was a pivotal event during Martin Van Buren’s presidency, exacerbating tensions between the United States and Great Britain. It began when rebellions erupted in Upper and Lower Canada, prompting American sympathizers to support Canadian rebels. William Lyon Mackenzie, a leader of the Upper Canadian rebels, sought refuge in the United States and organized an invasion force on Navy Island in the Niagara River.

To thwart the invasion, British forces crossed into American territory in late December 1837 and attacked the steamboat Caroline, which was supplying Mackenzie’s forces. In the ensuing skirmish, the Caroline was set ablaze, resulting in the death of an American and further inflaming anti-British sentiment in the U.S.

The incident sparked outcry for retaliation and potential war with Britain among American citizens and politicians. However, Van Buren, keen to avoid a costly conflict, dispatched General Winfield Scott to the Canada–United States border with broad discretionary powers to maintain peace and protect American interests. Scott’s diplomacy helped defuse tensions, and Van Buren proclaimed American neutrality in the Canadian independence issue in early 1838. Congress endorsed this stance by passing a neutrality law aimed at preventing American involvement in foreign conflicts.

Patriot War of 1837–1838

The Patriot War, also known as the Canadian Rebellions of 1837–1838, involved American sympathizers known as the Hunters’ Lodge operating out of Vermont. Led by Charles Duncombe and Robert Nelson, this secret society conducted raids and incursions into Upper Canada between December 1837 and December 1838. Their goal was to support Canadian rebels and overthrow British rule in the region.

Van Buren’s administration vigorously enforced neutrality laws to prevent American citizens from participating in these raids, thereby avoiding direct military confrontation with Britain. Despite sympathies among some Americans for Canadian independence, Van Buren maintained diplomatic efforts to uphold peace and stability along the border.

Northern Maine: The Aroostook “War”

In addition to conflicts with Canada, Van Buren faced a territorial dispute with Great Britain over northern Maine, an area claimed by both Maine and New Brunswick. Tensions escalated in late 1838 when New Brunswick lumbermen clashed with American woodcutters near the Aroostook River. Known as the Battle of Caribou, this incident heightened fears of armed conflict between the U.S. and Britain.

Maine’s governor, John Fairfield, mobilized state militias in response, and calls for military action reverberated throughout Congress and the American press. Van Buren, however, pursued a diplomatic approach and met with the British minister to negotiate a peaceful resolution. He dispatched General Winfield Scott to the disputed area to defuse tensions and prevent further escalation.

The border dispute was eventually resolved with the signing of the Webster–Ashburton Treaty in 1842, which established the current boundary between Maine and New Brunswick. Van Buren’s handling of these border conflicts underscored his commitment to diplomacy and his efforts to maintain peace amid regional and international tensions.

Amistad Case: Victory for the Ex-Slaves

The Amistad case of 1839 was a landmark legal battle with profound international implications, ultimately decided by the U.S. Supreme Court during Martin Van Buren’s presidency. The case arose from a rebellion aboard the Spanish schooner La Amistad, where African slaves took control of the ship while en route to Cuba. The vessel ended up in American waters and was seized by U.S. authorities.

Van Buren, who viewed abolitionism as a threat to national unity, initially supported Spain’s claim to have the ship and its cargo—including the Africans—returned. However, abolitionist lawyers intervened, arguing for the Africans’ freedom. A federal district court judge ruled in favor of the Africans’ freedom, a decision Van Buren’s administration appealed to the Supreme Court.

In February 1840, the case reached the Supreme Court, where former President John Quincy Adams passionately argued for the Africans’ right to freedom. Van Buren’s Attorney General, Henry D. Gilpin, presented the government’s case. In March 1841, the Supreme Court issued its final verdict, declaring the Amistad Africans free individuals who should be allowed to return home.

This case attracted widespread public interest due to its unique circumstances, including the participation of John Quincy Adams in court, the Africans’ testimony, and the prominence of the lawyers involved. It became a focal point in the growing abolitionist movement, highlighting the personal tragedies of slavery and igniting new support for abolitionism in the North. Moreover, it transformed the courts into a central arena for national debates on slavery’s legal foundations.

Judicial Appointments

During his presidency, Martin Van Buren made significant judicial appointments, including two Associate Justices to the Supreme Court: John McKinley (confirmed September 25, 1837) and Peter Vivian Daniel (confirmed March 2, 1841). Additionally, he appointed eight federal judges to various United States district courts, shaping the federal judiciary during his tenure.

White House Hostess

In the early years of his presidency, Martin Van Buren, a widower, assumed the role of White House host himself. However, following his son Abraham Van Buren’s marriage to Angelica Singleton in 1838, he appointed her as the official White House hostess. Angelica sought advice from Dolley Madison, her distant relative, who had returned to Washington after her husband’s death.

Under Angelica’s influence, White House social events became livelier and more refined. Her style, influenced by European court customs she admired during visits to England and France, attracted media attention. This attention, however, became fodder for political attacks against Van Buren, including the infamous “Gold Spoon Oration” by Pennsylvania Whig Congressman Charles Ogle. Criticizing Van Buren’s perceived royal lifestyle and his administration’s handling of economic issues during a severe depression, Ogle’s attack contributed to Van Buren’s defeat in the 1840 presidential election.

Presidential Election of 1840

The 1840 United States presidential election was a pivotal contest that marked the end of Martin Van Buren’s presidency and the rise of the Whig Party under William Henry Harrison. Van Buren, despite winning renomination at the 1840 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore, faced significant challenges.

Van Buren’s Presidency and Democratic Challenges

Van Buren’s first term as president was marked by economic turmoil, exacerbated by the Panic of 1837 and the ensuing depression. His administration’s handling of economic issues, along with contentious topics like slavery and western expansion, provided ample ammunition for his opponents, both within and outside the Democratic Party. Despite his difficulties, Van Buren was supported for renomination, although concerns over his vice president, Richard Mentor Johnson, led to contentious discussions within the party.

The Whig Strategy and Nomination of Harrison

The Whig National Convention of 1839 took a surprising turn by nominating William Henry Harrison, a hero of the War of 1812 known for his role in the Battle of Tippecanoe, over more established Whig figures like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. The Whigs believed Harrison’s military background and appeal as a man of the people would resonate strongly with voters. John Tyler of Virginia was chosen as Harrison’s running mate.

Campaign Themes and Strategies

The campaign was characterized by stark contrasts: Whigs portrayed Harrison as a humble man of the frontier, contrasting sharply with their depiction of Van Buren as an aristocrat out of touch with the common people. Campaign slogans like “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” emphasized Harrison’s military record and populist appeal, while ridiculing Van Buren’s perceived elitism and economic policies.

Election Outcome and Impact

In a campaign marked by high voter turnout and vigorous political attacks, Harrison won convincingly both in the popular vote (1,275,612 to 1,130,033) and in the electoral college (234 to 60). The Whigs also secured majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate for the first time. Despite Van Buren actually gaining more votes than he did in 1836, the Whigs’ effective mobilization of new voters and their strategic messaging ensured Harrison’s victory.

Legacy and Historical Significance

The election of 1840 marked a turning point in American politics, highlighting the power of strategic campaigning and populist appeals. It solidified the Whig Party’s influence and signaled the end of Van Buren’s presidency, whose tenure was overshadowed by economic woes and political challenges. The Whigs’ success in 1840 would shape future electoral strategies and set the stage for subsequent political developments in the United States.

Post-presidency (1841–1862)

Election of 1844

After the expiration of his presidency in 1841, Martin Van Buren returned to his estate at Lindenwald in Kinderhook, New York. He remained deeply engaged in national politics, closely observing developments such as the power struggles within the Whig Party under President John Tyler following William Henry Harrison’s death. While Van Buren did not immediately commit to another presidential run, he strategically undertook trips to the Southern and Western United States, where he met with influential figures like Andrew Jackson and James K. Polk, among others.

During this period, potential challengers for the 1844 Democratic nomination, including John Tyler, James Buchanan, and Levi Woodbury, emerged, but it was John C. Calhoun who posed the most significant obstacle. Van Buren initially avoided taking public stances on contentious issues like the Tariff of 1842, hoping to cultivate a groundswell of support for his candidacy.

However, the annexation of Texas emerged as a pivotal issue. President Tyler and his administration, with Calhoun now playing a key role, pushed aggressively for annexation to expand slavery into new territories. Van Buren, concerned about the implications for war with Mexico and the extension of slavery, initially kept his stance private. Eventually, he publicly opposed immediate annexation, which cost him support among pro-slavery Democrats.

Election of 1844

At the 1844 Democratic National Convention, Van Buren’s cautious stance on Texas led to his initial lead in delegate votes, but he failed to secure the required two-thirds majority. Facing strong opposition and the implementation of the two-thirds rule for nominations, Van Buren withdrew his candidacy after several ballots. Ultimately, James K. Polk emerged as the Democratic nominee, with Van Buren reluctantly endorsing him to unify the party against Whig candidate Henry Clay.

Following Polk’s election victory, despite being offered the ambassadorship to London, Van Buren declined due to his discontent with the treatment of his supporters at the convention and his general satisfaction with retirement. His relationship with the Polk administration further deteriorated over patronage issues, leading to a permanent estrangement from Polk and his policies.

Martin Van Buren’s post-presidential years continued to reflect his active engagement in political affairs, strategic maneuvering within the Democratic Party, and his enduring influence on national politics despite not holding elected office.

Martin Van Buren’s post-presidential career after leaving office in 1841 was marked by his continued involvement in national politics, particularly during the election of 1844.

Van Buren’s Candidacy

In the lead-up to the 1844 presidential election, Martin Van Buren sought to secure the Democratic nomination for a second presidential run. His candidacy faced significant challenges, particularly from factions within the Democratic Party that favored a more aggressive stance on the annexation of Texas.

Annexation of Texas and Political Maneuvering

The annexation of Texas emerged as a pivotal issue during the campaign. Van Buren initially took a cautious stance, opposing immediate annexation due to concerns over its potential to exacerbate sectional tensions and provoke war with Mexico. His position on Texas, however, drew criticism from expansionist Democrats and southerners who supported annexation.

Democratic National Convention

At the Democratic National Convention held in Baltimore, Van Buren’s cautious stance on Texas played a decisive role in his defeat. Pro-annexation Democrats rallied behind James K. Polk of Tennessee, a fervent supporter of territorial expansion. Despite Van Buren’s experience and stature within the party, the Texas issue divided Democratic delegates, leading to Polk’s nomination as the Democratic candidate for president.

Legacy of the Election

Van Buren’s loss in the 1844 election marked the end of his active presidential ambitions. The election highlighted the growing importance of territorial expansion and manifest destiny in American politics, themes that would shape subsequent administrations and influence the nation’s westward expansion.

Later Years and Legacy

Following his defeat in 1844, Van Buren continued to participate in public life, offering counsel and commentary on political developments. He remained a respected elder statesman within the Democratic Party and occasionally weighed in on national debates until his death in 1862.

Martin Van Buren’s post-presidential years reflected his enduring commitment to political service and his role in shaping American political discourse during a period of significant transformation and expansion.

Retirement

After the 1848 election, Martin Van Buren retired from seeking public office but remained deeply engaged in national politics. Here’s a summary of his activities and positions during the subsequent years:

Compromise of 1850 and Political Views:

Van Buren was troubled by the growing secessionist sentiments in the South but welcomed the Compromise of 1850 as a necessary measure to maintain national unity, despite his opposition to specific provisions like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. He continued to follow and analyze political developments closely, advocating for conciliation between North and South.

Historical Work and European Tour:

During this period, Van Buren worked on a history of American political parties, reflecting on his extensive political career and the evolving party dynamics in the United States. He also embarked on a tour of Europe, becoming the first former U.S. president to visit Britain, where he likely engaged in diplomatic and personal endeavors.

Return to the Democratic Party:

Despite his earlier involvement with the Free Soil Party, Van Buren and his followers eventually rejoined the Democratic fold. This decision was partly driven by concerns that continued division within the Democratic Party could strengthen the Whig Party, which was a significant political force at the time.

Political Endorsements and Views:

Van Buren supported Democratic candidates in subsequent presidential elections, including Franklin Pierce in 1852, James Buchanan in 1856, and Stephen A. Douglas in 1860. He viewed the emerging Know Nothing movement with disdain and criticized the Republican Party for exacerbating sectional tensions over slavery.

Criticism of Supreme Court Decisions and Civil War Support:

Van Buren condemned Chief Justice Roger Taney’s ruling in the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford case, which he viewed as a mistake for overturning the Missouri Compromise and inflaming anti-slavery sentiments. As tensions escalated with the secession of Southern states after Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, Van Buren publicly supported the Union cause once the Civil War began.

Efforts for National Unity:

In April 1861, former President Franklin Pierce proposed a meeting of living former presidents to seek a negotiated end to the Civil War. Pierce asked Van Buren, as the most senior living ex-president, to issue a formal call for such a gathering. Van Buren responded by suggesting that either Pierce or James Buchanan, the most recent former president, should take the lead, but nothing substantial came from the proposal.

Martin Van Buren’s later years were marked by his continued involvement in political discourse and his efforts to navigate the complex issues facing the nation, particularly regarding slavery and the preservation of the Union during the tumultuous Civil War era.

Death

Martin Van Buren’s final years and passing are poignant reflections of his enduring presence in American politics:

Health Decline and Passing:

In late 1861, Van Buren’s health began to deteriorate, and he was bedridden with pneumonia during the fall and winter. He ultimately succumbed to bronchial asthma and heart failure at his Lindenwald estate on July 24, 1862, at 2:00 a.m.

Legacy and Presidential Succession:

Van Buren’s death marked the end of an era in American politics. Remarkably, he outlived all four of his immediate successors: William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor. He also witnessed more successors ascend to the presidency than any other former president up to that point, a total of eight. Among these successors was Abraham Lincoln, whom Van Buren lived to see elected as the 16th President of the United States before his passing.

Burial and Family Legacy:

Van Buren was laid to rest in the Kinderhook Reformed Dutch Church Cemetery, alongside his wife Hannah, his parents, and his son Martin Van Buren Jr. His legacy extends beyond his political achievements to include his role as a statesman and his impact on the development of American democracy during a crucial period of expansion and division.

Martin Van Buren’s life and career spanned some of the most transformative decades in American history, leaving an indelible mark on the nation’s political landscape and its journey toward unity and progress.

Legacy

Historical reputation

Martin Van Buren’s legacy is shaped by his contributions to American politics and his influence during a pivotal period in the nation’s history:

Martin Van Buren’s legacy is multifaceted, encompassing both his significant contributions to American political organization and his mixed reception as a president:

- Political Organizer and Democratic Party Builder: Van Buren is widely recognized for his pivotal role in organizing and consolidating the Democratic Party during the Second Party System. He pioneered political techniques such as patronage, legislative caucuses, and party newspapers, which were crucial in building popular majorities and shaping modern party politics in the United States.

- Presidential Leadership: Despite his success as a political organizer, Van Buren’s presidency is often viewed as average or less successful. His tenure was marred by economic challenges, particularly the Panic of 1837, which led to widespread economic hardship and contributed to his defeat for reelection. Historians have debated the effectiveness of his response, including the Independent Treasury system.

- Historical Assessments and Controversies: Historical opinions on Van Buren’s presidency vary widely. While some, like libertarian writer Ivan Eland, praise his fiscal policies and crisis management during the Panic of 1837, others criticize his handling of economic issues and see his presidency as relatively unremarkable. Historian Jeffrey Rogers Hummel even considers Van Buren America’s greatest president, highlighting his achievements despite significant challenges.

- Legacy in Historical Memory: Van Buren’s presidency has often been described as forgettable or obscure in popular memory. Despite his foundational role in party politics and his efforts to shape democratic governance, he is not as prominently remembered as some other presidents of his era.

In summary, Martin Van Buren’s legacy is defined by his critical contributions to American political organization and the Democratic Party, contrasting with the more muted assessments of his presidential tenure. His impact on party politics and his views on democratic governance continue to be subjects of historical study and debate.

Memorials

Van Buren’s home in Kinderhook, New York, which he called Lindenwald, is now the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site. Several counties across the United States are named in his honor, including those in Michigan, Iowa, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Additionally, Mount Van Buren, the USS Van Buren, three state parks, and numerous towns bear his name.

Popular Culture

Books

In Gore Vidal’s 1973 novel “Burr,” a significant plot theme revolves around an attempt to prevent Van Buren’s election as president by alleging he is the illegitimate son of Aaron Burr.

Comic Strips

After the 1988 presidential campaign, George H. W. Bush, a Yale University graduate and member of the Skull and Bones secret society, became the first incumbent vice president to win the presidency since Van Buren. In the comic strip Doonesbury, artist Garry Trudeau humorously depicted members of Skull and Bones as stealing Van Buren’s skull as a congratulatory gift to the new president.

Currency

Martin Van Buren appeared in the Presidential dollar coin series in 2008. Additionally, the U.S. Mint issued commemorative silver medals for Van Buren, released for sale in 2021.

Film and TV

Van Buren is portrayed by Nigel Hawthorne in the 1997 film Amistad. The film depicts the legal battle surrounding the status of slaves who, in 1839, rebelled against their transporters on the La Amistad slave ship.

On the television show Seinfeld, the 1997 episode “The Van Buren Boys” features a fictional street gang that admires Van Buren. The gang bases its rituals and symbols on him, including a hand sign of eight fingers pointing up to signify Van Buren, the eighth president.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Van_Buren