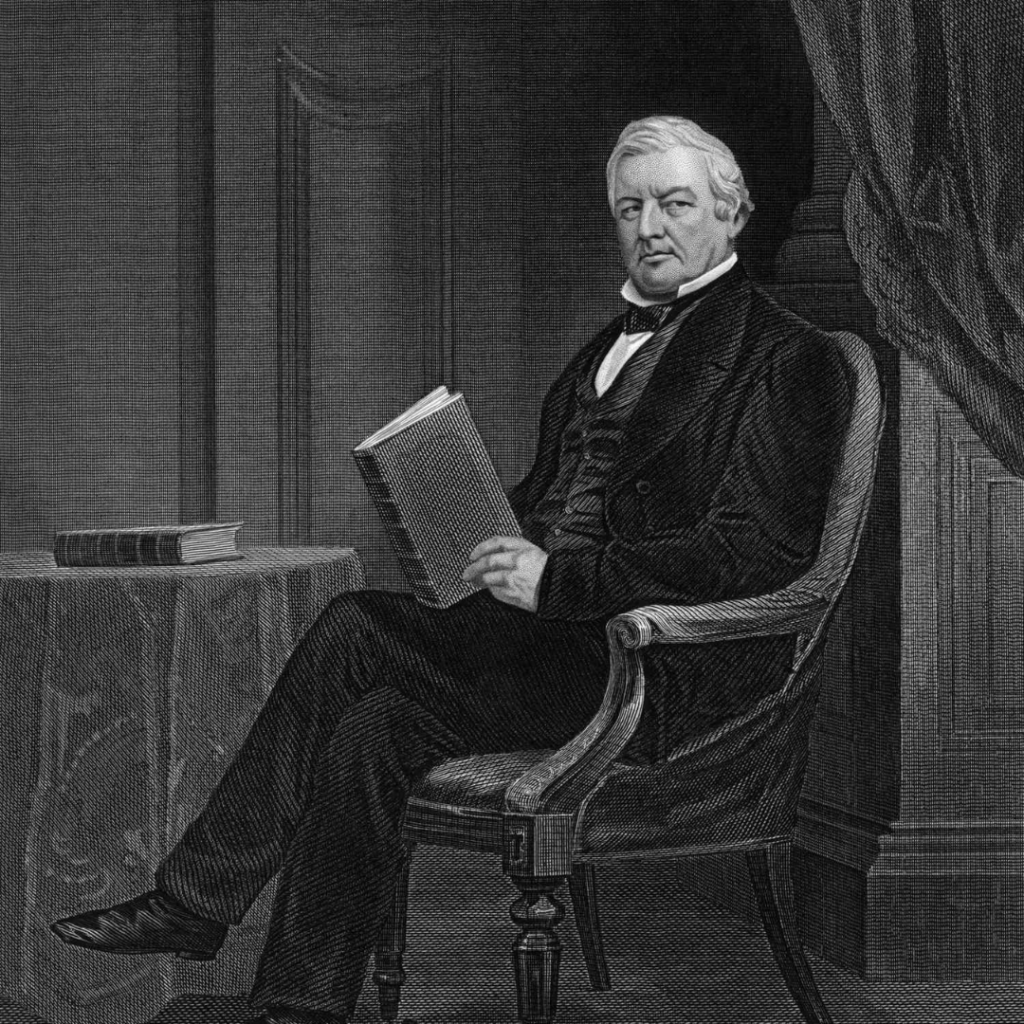

Millard Fillmore, the 13th President of the United States, served from 1850 to 1853 after the sudden death of President Zachary Taylor. Fillmore was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. His presidency is often noted for the Compromise of 1850, which sought to ease tensions between slave and free states. This compromise included the controversial Fugitive Slave Act, which Fillmore enforced, leading to considerable criticism from abolitionists.

After his presidency, Fillmore continued to be active in politics, running unsuccessfully as a candidate for the Know-Nothing Party in the 1856 presidential election. His legacy is a complex one, marked by attempts to maintain unity in a deeply divided nation, yet also by policies that exacerbated sectional conflicts.

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) served as the 13th President of the United States from 1850 to 1853. He was the final president affiliated with the Whig Party during his tenure. Initially a U.S. House of Representatives member, Fillmore was elected as the 12th Vice President in 1848. He ascended to the presidency after Zachary Taylor’s death in July 1850. Fillmore played a crucial role in enacting the Compromise of 1850, which temporarily mitigated the conflict over slavery expansion.

Fillmore was born in poverty in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. Despite minimal formal education, he self-studied to become a lawyer. Gaining prominence in Buffalo, he was elected to the New York Assembly in 1828 and the House of Representatives in 1832. Initially part of the Anti-Masonic Party, he later joined the Whig Party in the mid-1830s. He contended for state party leadership with editor Thurlow Weed and his protégé, William H. Seward.

Fillmore condemned slavery as evil but believed it was beyond the federal government’s jurisdiction to abolish it, contrasting with Seward’s stance that the government should actively oppose it. Though he lost the bid for Speaker of the House in 1841, he chaired the Ways and Means Committee. After unsuccessful campaigns for vice president and New York governor in 1844, Fillmore was elected New York Comptroller in 1847, the first to do so by direct election.

As Vice President, Fillmore was marginalized by Taylor but presided over heated Senate debates regarding slavery in the Mexican Cession. Unlike Taylor, Fillmore endorsed Henry Clay’s omnibus bill, forming the Compromise of 1850. Upon assuming the presidency in July 1850, he replaced Taylor’s cabinet and urged Congress to adopt the compromise. He enforced the contentious Fugitive Slave Act, harming his popularity and fracturing the Whig Party. In foreign affairs, Fillmore supported U.S. naval expeditions to Japan, resisted French ambitions in Hawaii, and faced embarrassment from Narciso López’s filibuster missions to Cuba. He failed to secure the Whig presidential nomination in 1852.

Following his presidency, as the Whig Party disintegrated, Fillmore and its conservative faction joined the Know-Nothings, forming the American Party. During his 1856 presidential run, he focused on Union preservation over anti-immigration rhetoric, securing only Maryland. During the Civil War, Fillmore condemned secession and backed the Union’s maintenance by force but criticized Lincoln’s policies. After the war, he supported Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction efforts. Fillmore remained civically engaged, notably as chancellor of the University of Buffalo, which he co-founded in 1846. Historians often rank Fillmore poorly, mainly due to his slavery policies and his association with the Know-Nothings and Johnson’s Reconstruction policies, which further marred his legacy.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

- 13th President of the United States

Early Life and Career

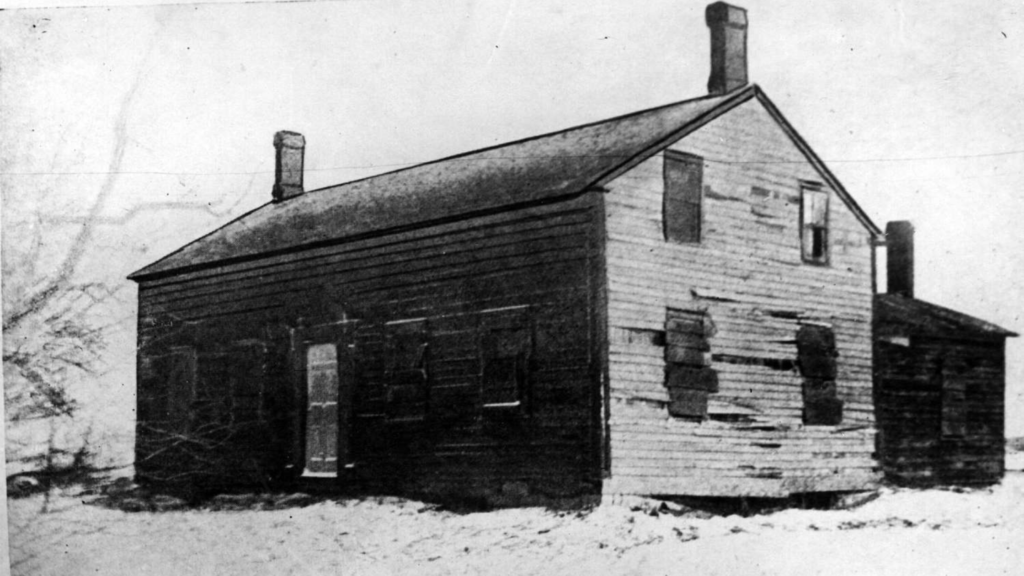

Millard Fillmore was born on January 7, 1800, in a log cabin on a farm in present-day Moravia, in New York’s Finger Lakes region. His parents, Phoebe Millard and Nathaniel Fillmore, had eight children, with Millard being the second and oldest son. The Fillmore family traced their roots back to England, with their ancestor John Fillmore arriving in Ipswich, Massachusetts, during colonial times.

Nathaniel Fillmore, Millard’s father, was the son of Nathaniel Fillmore Sr., an early settler in Bennington, Vermont. In 1799, Nathaniel and Phoebe moved from Vermont seeking better opportunities. However, they encountered difficulties with the title to their Cayuga County land, forcing them to relocate to nearby Sempronius, where they became tenant farmers. Despite these challenges, Nathaniel occasionally taught school and eventually gained local respect, serving in roles such as justice of the peace.

Millard’s childhood was marked by hard work, scarcity, and minimal formal education. His father hoped he would learn a trade and discouraged him from enlisting in the War of 1812. Instead, at age 14, Millard was apprenticed to clothmaker Benjamin Hungerford in Sparta, where he performed menial labor. Dissatisfied, he left Hungerford and later worked at a mill in New Hope. Driven by a desire for self-improvement, Millard invested in a circulating library and read extensively.

In 1819, Millard enrolled at a new academy in New Hope during idle times at the mill, where he met Abigail Powers, who later became his wife. Later that year, the Fillmore family moved to Montville, a hamlet of Moravia. Recognizing Millard’s potential, Nathaniel persuaded Judge Walter Wood to employ Millard as a law clerk. Millard financed his legal studies by teaching school and eventually bought out his mill apprenticeship. After an 18-month stint with Judge Wood, during which he earned little and had disagreements, Millard left to pursue his path.

The family then moved to East Aurora, near Buffalo, where Nathaniel purchased a prosperous farm. By 1821, Millard had reached adulthood and taught school while handling minor legal cases. In 1822, he moved to Buffalo to further his legal studies and became engaged to Abigail Powers. After being admitted to the bar in 1823, he chose to establish his practice in East Aurora rather than Buffalo, enjoying the independence it offered.

Millard Fillmore and Abigail Powers married on February 5, 1826, and had two children: Millard Powers Fillmore (1828–1889) and Mary Abigail Fillmore (1832–1854).

Buffalo Politician

Millard Fillmore, alongside other members of his family who were active in politics and government, found his political footing with the rise of the Anti-Masonic Party in the late 1820s. The Anti-Masons opposed the presidential candidacy of General Andrew Jackson, a Mason. Fillmore attended the New York convention that endorsed President John Quincy Adams for re-election and participated in two Anti-Masonic conventions in the summer of 1828. It was at these conventions that Fillmore first encountered Thurlow Weed, a newspaper editor and future political rival.

Fillmore emerged as a prominent figure in East Aurora, where he had built a house and lived from 1826 to 1830. He was elected to the New York State Assembly, serving three one-year terms from 1829 to 1831. Despite being in the minority, as the Jacksonian Democrats had swept their candidate into the White House and secured a majority in Albany, Fillmore successfully promoted significant legislation. He advocated for allowing court witnesses to take non-religious oaths and for abolishing imprisonment for debt in 1830.

By 1830, Fillmore’s legal practice had largely moved to Buffalo, where he relocated with his family. Buffalo, recovering from the British attacks during the War of 1812 and rapidly expanding as the western terminus of the Erie Canal, offered ample opportunities for Fillmore. He became a prominent lawyer, taking on cases from outside Erie County and building a reputation in Buffalo. He partnered with his lifelong friend Nathan K. Hall, who later became his partner in Buffalo and served as his postmaster general during his presidency. Fillmore also played a role in drafting Buffalo’s city charter, although the bill to incorporate Buffalo as a city passed the legislature after he left the Assembly.

In addition to his legal career, Fillmore was deeply involved in the Buffalo community. He helped found the Buffalo High School Association, joined the local lyceum, attended the Unitarian church, and became a leading citizen. He was also active in the New York Militia, attaining the rank of major as inspector of the 47th Brigade. Fillmore’s contributions to Buffalo’s growth and his legal and political accomplishments cemented his status as a key figure in the city’s history.

Representative

First Term and Return to Buffalo

In 1832, Millard Fillmore successfully ran for the U.S. House of Representatives. The Anti-Masonic presidential candidate, William Wirt, managed to win only Vermont, while President Andrew Jackson easily secured re-election. At that time, Congress convened its annual session in December, meaning Fillmore had to wait over a year after his election to take his seat. Recognizing that opposition to Masonry alone was insufficient for building a national party, Fillmore, Thurlow Weed, and others formed the Whig Party.

This new party combined National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and disaffected Democrats, united by their opposition to Jackson and a platform promoting economic growth through the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States and federally funded internal improvements such as roads, bridges, and canals.

In Washington, Fillmore advocated for the expansion of Buffalo harbor, which was under federal jurisdiction, and lobbied Albany for the expansion of the state-owned Erie Canal. Although his affiliation with the Anti-Masons was uncertain even during the 1832 campaign, Fillmore quickly shed the label once in office. He caught the attention of influential Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster, who became a mentor. Fillmore strongly supported Webster and they maintained a close relationship until Webster’s death late in Fillmore’s presidency.

Fillmore supported the Second Bank as a means for national development, though he did not speak in the congressional debates about renewing its charter after Jackson’s veto. He voted in favor of infrastructure improvements, such as navigation enhancements on the Hudson River and the construction of a bridge across the Potomac River.

Anti-Masonry remained strong in Western New York, though it was fading nationally. When the Anti-Masons did not nominate him for a second term in 1834, Fillmore declined the Whig nomination, believing that the two parties would split the anti-Jackson vote and elect a Democrat. After leaving office, he focused on building his law practice and bolstering the Whig Party, which gradually absorbed most of the Anti-Masons. By 1836, confident of anti-Jackson unity, Fillmore accepted the Whig nomination for Congress. Despite the Democrats’ nationwide victory, led by Vice President Martin Van Buren, Western New York voted Whig, returning Fillmore to Washington.

Second to Fourth Terms

Facing the economic Panic of 1837, President Van Buren called a special session of Congress. Van Buren proposed placing government funds in sub-treasuries, which would not lend money. Fillmore opposed this, believing it would lock away the nation’s limited supply of gold money. Despite Van Buren’s proposals passing, the Whigs gained increased votes in the 1837 elections and captured the New York Assembly, leading to a battle for the 1838 gubernatorial nomination. Fillmore supported Francis Granger, the leading Whig vice-presidential candidate from 1836, but Weed preferred William H. Seward. Although embittered by Weed’s success in securing Seward’s nomination, Fillmore campaigned loyally, leading to Seward’s election and Fillmore’s return to the House.

The rivalry between Fillmore and Seward intensified due to the growing anti-slavery movement. While Fillmore disliked slavery, he did not view it as a political issue. In contrast, Seward was openly hostile to slavery, as demonstrated by his actions as governor, such as refusing to return escaped slaves. When Fillmore was proposed for the position of vice-chancellor of the eighth judicial district in 1839, Seward rejected the nomination and instead chose Frederick Whittlesey.

As the Whig National Convention for the 1840 presidential race approached, Fillmore initially supported General Winfield Scott, aiming to defeat Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, a slaveholder who Fillmore believed could not win New York State. Although Fillmore did not attend the convention, he was pleased when General William Henry Harrison was nominated for president, with former Virginia Senator John Tyler as his running mate. Fillmore organized Western New York for the Harrison campaign, and both the national ticket and Fillmore himself won their elections.

When Harrison died shortly after taking office, Tyler became president and soon broke with the Whig leadership over proposals for a national bank. Fillmore, as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, prepared the Tariff of 1842 to raise tariff rates, gaining political advantage for the Whigs and isolating Tyler politically. Despite receiving praise for the tariff, Fillmore announced he would not seek re-election in July 1842. Tired of Washington life and political conflicts, Fillmore returned to Buffalo in April 1843. His biographer, Scarry, noted that Fillmore concluded his Congressional career as a powerful figure and an able statesman at the height of his popularity.

Weed regarded Fillmore as “able in debate, wise in council, and inflexible in his political sentiments.”

National Figure

Out of office, Millard Fillmore continued his law practice and made long-neglected repairs to his Buffalo home. He remained a significant political figure and led the committee that welcomed John Quincy Adams to Buffalo, where the former president expressed regret at Fillmore’s absence from Congress. Some urged Fillmore to run for vice president with Henry Clay, the consensus Whig choice for president in 1844. Horace Greeley privately wrote, “my own first choice has long been Millard Fillmore,” and others thought Fillmore should aim for the governor’s mansion for the Whigs. Seeking a return to Washington, Fillmore desired the vice presidency.

Fillmore hoped to gain the endorsement of the New York delegation to the national convention, but Thurlow Weed wanted the vice presidency for William H. Seward, with Fillmore as governor. However, Seward withdrew before the 1844 Whig National Convention. When Weed’s replacement vice presidential hopeful, Willis Hall, fell ill, Weed sought to defeat Fillmore’s candidacy, aiming to force him to run for governor. Weed’s attempts to boost Fillmore as a gubernatorial candidate caused Fillmore to write, “I am not willing to be treacherously killed by this pretended kindness … do not suppose for a minute that I think they desire my nomination for governor.”

New York sent a delegation to the convention in Baltimore pledged to support Clay but with no instructions for vice president. Weed told out-of-state delegates that the New York party preferred Fillmore as its gubernatorial candidate, leading to former New Jersey senator Theodore Frelinghuysen being nominated for vice president after Clay was nominated for president.

Despite his defeat, Fillmore met and publicly appeared with Frelinghuysen and quietly rejected Weed’s offer to get him nominated as governor at the state convention. Fillmore’s stance on opposing slavery only at the state level made him an acceptable statewide Whig candidate, and Weed ensured that pressure on Fillmore increased. Despite his reluctance, Fillmore stated that a convention had the right to draft anyone for political service, and Weed got the convention to choose Fillmore, who had broad support.

The Democrats nominated Senator Silas Wright as their gubernatorial candidate and former Tennessee Governor James K. Polk for president. Although Fillmore worked to gain support among German-Americans, he was hurt among immigrants by the Whigs’ support of a nativist candidate in the New York City mayoral election earlier in 1844. Fillmore blamed his defeat on “foreign Catholics.” Clay also lost the presidential election. Fillmore’s biographer Paul Finkelman suggested that Fillmore’s hostility to immigrants and his weak position on slavery led to his defeat for governor.

In 1846, Fillmore was involved in founding what is now the University at Buffalo, becoming its first chancellor and serving until his death in 1874. He opposed the annexation of Texas, spoke against the subsequent Mexican–American War, and viewed the war as a means to extend slavery. Fillmore was angered when President Polk vetoed a river and harbors bill that would have benefited Buffalo, writing, “May God save the country for it is evident the people will not.” At the time, New York governors served two-year terms, and Fillmore could have had the Whig nomination in 1846.

Instead, he maneuvered to get the nomination for his supporter, John Young, who was elected. A new constitution for New York State made the office of comptroller elective, and Fillmore’s work in finance made him an obvious candidate. He successfully secured the Whig nomination for the 1847 election and won by 38,000 votes, the largest margin a Whig candidate for statewide office would achieve in New York.

Before moving to Albany to take office on January 1, 1848, Fillmore left his law firm and rented out his house. He received positive reviews for his service as comptroller, during which he supported the expansion of the state canal board and ensured competent management. He secured an enlargement of Buffalo’s canal facilities. As comptroller, Fillmore regulated banks, stabilizing the currency by requiring state-chartered banks to keep New York and federal bonds equal to the value of the banknotes they issued—a plan later adopted by Congress in 1864.

Election of 1848

Nomination

With President Polk’s decision not to seek a second term and Whig gains in Congress during the 1846 election cycle, the Whigs were optimistic about capturing the White House in 1848. The party had prominent figures like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster vying for the nomination, but many Whigs supported the Mexican War hero, General Zachary Taylor. Taylor’s popularity was tempered by concerns from Northerners about electing a Louisiana slaveholder during a time of sectional tensions over slavery in the newly acquired territories from Mexico. Taylor’s political views were also a mystery to many, as his military career had kept him from casting a presidential ballot, raising fears of another Tyler or Harrison scenario.

As the nomination remained undecided, Thurlow Weed, a key New York political operator, sought to send an uncommitted delegation to the 1848 Whig National Convention in Philadelphia. His goal was to position himself as a kingmaker, hoping to place ex-Governor Seward on the ticket or secure a high federal office for him. Weed persuaded Fillmore to support an uncommitted ticket but kept his ambitions for Seward hidden from him. Despite Weed’s efforts, Taylor secured the nomination on the fourth ballot, causing frustration among Clay’s supporters and Conscience Whigs from the Northeast.

John A. Collier, a New Yorker opposing Weed, addressed the convention, advocating for Fillmore as a vice-presidential candidate to prevent a party split. Collier’s speech, portraying Fillmore as a staunch Clay supporter, was well-received despite inaccuracies. This resulted in Fillmore’s nomination for vice president on the second ballot, overcoming Taylor’s managers’ preference for Abbott Lawrence of Massachusetts.

Weed’s plans were further thwarted as Fillmore’s vice-presidential nomination meant no other New Yorker could be appointed to the Cabinet, diminishing Seward’s prospects. Fillmore’s selection was strategic due to his electoral significance in New York and his adherence to Whig principles, which assuaged concerns of another potential Tyler presidency. His rivalry with Seward, known for his anti-slavery stance, made Fillmore more acceptable to the South.

General Election

During the mid-19th century, it was customary for high office candidates to avoid actively campaigning. Thus, Fillmore remained at the comptroller’s office in Albany, refraining from making speeches. The 1848 campaign unfolded through newspapers and surrogate speeches at rallies. The Democrats nominated Senator Lewis Cass for president and General William O. Butler as his running mate, while the Free Soil Party, opposing slavery’s expansion, chose ex-President Van Buren.

A crisis emerged among the Whigs when Taylor also accepted the presidential nomination from a faction of South Carolina Democrats. Fearing Taylor might become a party renegade like Tyler, Weed organized a rally in Albany to elect an uncommitted slate of presidential electors. Fillmore assured Weed of Taylor’s loyalty to the party, resolving the crisis.

Fillmore’s stance on slavery was nuanced; he considered it an evil but believed the federal government had no authority over it. This position made him a palatable choice for both Northerners and Southerners, despite Southern accusations of him being an abolitionist.

Ultimately, the Taylor-Fillmore ticket narrowly won the election, with New York’s electoral votes playing a crucial role. The Whig ticket secured the popular vote with 47.3% to the Democrats’ 42.5%, winning the Electoral College by 163 to 127 votes. Although minor party candidates took no electoral votes, the significant anti-slavery sentiment was evident in Van Buren’s 10.1% share of the popular vote.

Vice Presidency (1849–1850)

Fillmore was sworn in as vice president on March 5, 1849, in the Senate Chamber, deferring the ceremony from March 4 since it fell on a Sunday. He took the oath from Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and administered the oath to incoming senators, including Seward.

During the four months between the election and the inauguration, Fillmore was celebrated by New York Whigs and concluded his duties as comptroller. Taylor, mistakenly thinking the vice president was a cabinet member, promised Fillmore influence in the administration. However, Seward and Weed, seeking to control federal job appointments in New York, undermined Fillmore’s influence, despite their earlier agreement. This political maneuvering diminished Fillmore’s authority, leading to a power struggle within the Whig Party.

Despite these challenges, Fillmore found solace in his role with the Smithsonian Institution, reflecting his lifelong passion for learning.

In 1849, the issue of slavery in the territories remained unresolved. Taylor supported the admission of California and New Mexico as free states, despite being a Southern slaveholder. This stance surprised Southerners and heightened sectional tensions, particularly in Congress, where the election of the Speaker took weeks and multiple ballots.

To counter the Weed machine, Fillmore built a network of like-minded Whigs and gained support from wealthy New Yorkers. Their efforts led to the establishment of a rival newspaper to Weed’s Albany Evening Journal, further intensifying the political rivalry.

As vice president, Fillmore presided over intense debates regarding the extension of slavery into new territories. In January 1850, President Taylor proposed admitting California and New Mexico as free states, igniting further discord. Clay’s “Omnibus Bill,” introduced later that month, sought a compromise by admitting California as a free state, organizing territorial governments in New Mexico and Utah, banning the slave trade in the District of Columbia, and strengthening the Fugitive Slave Act. Although Taylor was lukewarm about the bill, Fillmore indicated his support by promising to cast a tie-breaking vote in its favor if necessary. Despite Fillmore’s efforts to maintain order, debates were often heated, culminating in a physical confrontation between senators Foote and Benton.

Fillmore’s tenure as vice president was marked by his efforts to navigate the Whig Party’s internal conflicts and the nation’s sectional divisions over slavery.

Presidency (1850–1853)Succession Amid Crisis

July 4, 1850, was a very hot day in Washington, and President Taylor, who attended the Fourth of July ceremonies to lay the cornerstone of the Washington Monument, refreshed himself, likely with cold milk and cherries. What he consumed likely gave him gastroenteritis, and he died on July 9. Taylor, nicknamed “Old Rough and Ready,” had gained a reputation for toughness through his military campaigning in the heat, and his sudden death came as a shock to the nation.

Fillmore had been called from his chair presiding over the Senate on July 8 and had sat with members of the cabinet in a vigil outside Taylor’s bedroom at the White House. He received the formal notification of the president’s death, signed by the cabinet, on the evening of July 9 in his residence at the Willard Hotel. After acknowledging the letter and spending a sleepless night, Fillmore went to the House of Representatives, where, at a joint session of Congress, he took the oath as president from William Cranch, the chief judge of the federal court for the District of Columbia, who had also sworn in President Tyler.

The cabinet officers, as was customary when a new president took over, submitted their resignations but expected Fillmore to refuse and to allow them to continue in office. Fillmore had been marginalized by the cabinet members, and he accepted the resignations though he asked them to stay on for a month, which most refused to do. Fillmore is the only president who succeeded by death or resignation not to retain, at least initially, his predecessor’s cabinet. He was already in discussions with Whig leaders and, on July 20, began to send new nominations to the Senate, with the Fillmore Cabinet to be led by Webster as Secretary of State.

Webster had outraged his Massachusetts constituents by supporting Clay’s bill and, with his Senate term to expire in 1851, had no political future in his home state. Fillmore appointed his old law partner, Nathan Hall, as Postmaster General, a cabinet position that controlled many patronage appointments. The new department heads were mostly supporters of the Compromise, like Fillmore.

The brief pause from politics out of national grief at Taylor’s death did not abate the crisis. Texas had attempted to assert its authority in New Mexico, and the state’s governor, Peter H. Bell, had sent belligerent letters to President Taylor. Fillmore received another letter after he had become president. He reinforced federal troops in the area and warned Bell to keep the peace.

By July 31, Clay’s bill was effectively dead, as all significant provisions other than the organization of Utah Territory had been removed by amendment. As one wag put it, the “Mormons” were the only remaining passengers on the omnibus. Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas then stepped to the fore, with Clay’s agreement, proposing to break the omnibus bill into individual bills that could be passed piecemeal. Fillmore endorsed that strategy, which eventually divided the compromise into five bills.

Fillmore sent a special message to Congress on August 6, 1850; disclosed the letter from Governor Bell and his reply; warned that armed Texans would be viewed as intruders; and urged Congress to defuse sectional tensions by passing the Compromise. Without the presence of the Great Triumvirate of John C. Calhoun, Webster, and Clay, who had long dominated the Senate, Douglas and others were able to lead the Senate towards the administration-backed package of bills. Each bill passed the Senate with the support of the section that wanted it, with a few members who were determined to see all the bills passed.

The battle then moved to the House, which had a Northern majority because of the population. Most contentious was the Fugitive Slave Bill, whose provisions were anathema to abolitionists. Fillmore applied pressure to get Northern Whigs, including New Yorkers, to abstain, rather than to oppose the bill. Through the legislative process, various changes were made, including the setting of a boundary between New Mexico Territory and Texas, the state being given a payment to settle any claims

California was admitted as a free state, the District of Columbia’s slave trade was ended, and the final status of slavery in New Mexico and Utah would be settled later. Fillmore signed the bills as they reached his desk and held the Fugitive Slave Bill for two days until he received a favorable opinion as to its constitutionality from the new Attorney General, John J. Crittenden. Although some Northerners were unhappy at the Fugitive Slave Act, relief was widespread in the hope of settling the slavery question.

Domestic Affairs

The Fugitive Slave Act remained contentious after its enactment. Southerners complained bitterly about any leniency in its application, but its enforcement was highly offensive to many Northerners. Abolitionists recited the inequities of the law since anyone aiding an escaped slave was punished severely, and it granted no due process to the escapee, who could not testify before a magistrate. The law also permitted a higher payment to the hearing magistrate for deciding the escapee was a slave, rather than a free man.

Nevertheless, Fillmore believed himself bound by his oath as president and by the bargain that had been made in the Compromise to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. He did so even though some prosecutions or attempts to return slaves ended badly for the government, with acquittals and the slave taken from federal custody and freed by a Boston mob. Such cases were widely publicized North and South, inflamed passions in both places, and undermined the good feeling that had followed the Compromise.

In August 1850, the social reformer Dorothea Dix wrote to Fillmore to urge support of her proposal in Congress for land grants to finance asylums for the impoverished mentally ill. Though her proposal did not pass, they became friends, met in person, and continued to correspond well after Fillmore’s presidency.

In September 1850, Fillmore appointed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints leader Brigham Young as the first governor of Utah Territory. In gratitude, Young named the first territorial capital “Fillmore” and the surrounding county “Millard.”

A longtime supporter of national infrastructure development, Fillmore signed bills to subsidize the Illinois Central Railroad from Chicago to Mobile, and for a canal at Sault Ste. Marie. The 1851 completion of the Erie Railroad in New York prompted Fillmore and his cabinet to ride the first train from New York City to the shores of Lake Erie, in the company with many other politicians and dignitaries. Fillmore made many speeches along the way from the train’s rear platform, urged acceptance of the Compromise, and later went on a tour of New England with his Southern cabinet members. Although Fillmore urged Congress to authorize a transcontinental railroad, it did not do so until a decade later.

Fillmore appointed one justice to the Supreme Court of the United States and made four appointments to United States district courts, including that of his law partner and cabinet officer, Nathan Hall, to the federal district court in Buffalo. When Supreme Court Justice Levi Woodbury died in September 1851 with the Senate not in session, Fillmore made a recess appointment of Benjamin Robbins Curtis to the Court.

In December, with Congress convened, Fillmore formally nominated Curtis, who was confirmed. In 1857, Justice Curtis dissented from the Court’s decision in the slavery case of Dred Scott v. Sandford and resigned as a matter of principle.

Justice John McKinley’s death in 1852 led to repeated fruitless attempts by the president to fill the vacancy. The Senate took no action on the nomination of the New Orleans attorney Edward A. Bradford. Fillmore’s second choice, George Edmund Badger, asked for his name to be withdrawn. Senator-elect Judah P. Benjamin declined to serve. The nomination of William C. Micou, a New Orleans lawyer recommended by Benjamin, was not acted on by the Senate. The vacancy was finally filled after Fillmore’s term, when President Franklin Pierce nominated John Archibald Campbell, who was confirmed by the Senate.

Foreign Relations

Fillmore oversaw two highly-competent Secretaries of State, Daniel Webster, and after the New Englander’s 1852 death, Edward Everett. Fillmore looked over their shoulders and made all major decisions. He was particularly active in Asia and the Pacific, especially with regard to Japan, which then still prohibited nearly all foreign contact. American merchants and shipowners wanted Japan “opened up” for trade, which would allow commerce and permit American ships to call there for food and water and in emergencies without them being punished.

They were concerned that American sailors cast away on the Japanese coast were imprisoned as criminals. Fillmore and Webster dispatched Commodore Matthew C. Perry on the Perry Expedition to open Japan to relations with the outside world. Perry and his ships reached Japan in July 1853, four months after the end of Fillmore’s term.

Fillmore was a staunch opponent of European influence in Hawaii. France, under Emperor Napoleon III, sought to annex Hawaii but backed down after Fillmore issued a strongly-worded message warning that “the United States would not stand for any such action.”

Taylor had pressed Portugal for payment of American claims dating as far back as the War of 1812 and had refused offers of arbitration, but Fillmore gained a favorable settlement.

Fillmore had difficulties regarding Cuba since many Southerners hoped to see the island as an American slave territory. Cuba was a Spanish slave colony.

The Venezuelan adventurer Narciso López recruited Americans for three filibustering expeditions to Cuba in the hope of overthrowing Spanish rule. After the second attempt in 1850, López and some of his followers were indicted for breach of the Neutrality Act but were quickly acquitted by friendly Southern juries. The final López expedition ended with his execution by the Spanish, who put several

Post-Presidency (1853–1874)

Personal Tragedies

Millard Fillmore, the first president to return to private life without independent wealth or a landed estate, faced significant challenges after his presidency. Lacking a pension, Fillmore needed to find a way to support himself that would uphold the dignity of his former office. He considered practicing law in the higher courts of New York, a suggestion from his friend Judge Hall. Unfortunately, Fillmore’s plans were marred by personal losses.

His wife Abigail contracted pneumonia after catching a cold at President Pierce’s inauguration and passed away on March 30, 1853, in Washington. Fillmore returned to Buffalo for her burial, and his mourning period limited his social engagements. He managed to get by on income from his investments but was again struck by tragedy on July 26, 1854, when his only daughter, Mary, died of cholera.

Subsequent Political Activity

In early 1854, Fillmore re-emerged from seclusion as the debate over Senator Douglas’s Kansas–Nebraska Bill heated up. This bill aimed to open the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase to settlement and remove the Missouri Compromise’s restriction on slavery. Despite his absence from the Whig Party, which was divided by the new legislation, Fillmore retained many supporters. He planned a national tour under the guise of a nonpolitical endeavor while quietly rallying former Whig politicians to preserve the Union and support his potential presidential run. He made public appearances and engaged with politicians behind closed doors during late winter and spring 1854.

The rise of the Know Nothing Party, or the American Party, which originated from nativist organizations, provided a platform for Fillmore. By 1854, many from Fillmore’s “National Whig” faction had joined the Know Nothings, who had expanded their agenda beyond nativism. Encouraged by their midterm election success, Fillmore sent a letter in January 1855 warning against immigrant influence in American politics and joined the order.

Fillmore traveled to Europe and the Middle East from March 1855 to June 1856. This trip was advised by political friends to keep him away from contentious issues. During his travels, Fillmore met Queen Victoria and Pope Pius IX, although he nearly withdrew from the papal audience due to the expected protocol.

1856 Campaign Millard Fillmore

In 1856, Fillmore was nominated by the American Party for the presidency while still abroad. His running mate was Andrew Donelson of Kentucky. Fillmore made a notable return in June 1856, beginning with a large reception in New York City and traveling across New York State to Buffalo. Despite this, his campaign struggled as political figures moved toward the Republican Party and Fillmore’s pro-Union stance went largely unheard. The election saw Buchanan win with 45.3% of the vote, Frémont with 33.1%, and Fillmore with 21.6%, carrying only Maryland.

Remarriage, Later Life, and Death

After his defeat in 1856, Fillmore felt his political career was over and was hesitant to return to law practice. However, financial stability came when he married Caroline McIntosh, a wealthy widow, in February 1858. They purchased a large home in Buffalo, where they engaged in philanthropy and supported various causes, including the Buffalo General Hospital.

In the 1860 election, Fillmore voted for Senator Douglas, avoiding participation in the secession crisis. He supported Lincoln’s efforts to preserve the Union during the Civil War, commanding the Union Continentals, a corps of home guards. Despite his support, Fillmore faced criticism for his speech advocating reconciliation with the South, which was seen as a challenge to Lincoln’s administration.

In 1864, Fillmore supported Democratic nominee George B. McClellan, believing his plan for immediate cessation of fighting was the best path to restore the Union. Following Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, Fillmore was criticized for his lack of mourning but later hosted Lincoln’s funeral train in Buffalo.

Fillmore continued to support President Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction policies and devoted much of his time to civic activities, including aiding Buffalo in establishing an art gallery. He remained in good health until suffering a stroke in February 1874, followed by a second stroke, which led to his death on March 8, 1874. He was buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, with a funeral procession attended by many, including members of the U.S. Senate.

Legacy and Historical View

Millard Fillmore is frequently regarded by historians and political analysts as one of the least effective U.S. presidents. His approach to major issues, particularly slavery, has often been criticized as weak and ineffectual. Historian Scarry remarks that Fillmore has endured more ridicule than any other president, a sentiment echoed by President Harry S. Truman, who labeled him a “weak, trivial thumb-twaddler” and partly blamed him for the Civil War. Fillmore’s name has come to symbolize mediocrity in popular culture, as noted by Anna Prior in The Wall Street Journal in 2010.

Critics like Finkelman argue that Fillmore’s narrow vision on key issues and his pro-southern stance have marred his legacy. Nonetheless, some historians offer a more nuanced perspective. Rayback appreciates Fillmore’s “warmth and wisdom” in supporting the Union, while Smith recognizes him as a diligent president who upheld his oath by enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act, despite personal reservations.

Political scientists Steven G. Calabresi and Christopher S. Yoo describe Fillmore as “a faithful executor of the laws of the United States – for good and for ill.” Smith adds that Fillmore’s connection with the Know Nothings and his enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act have unfairly impacted his reputation. Despite some positive views on his role in the Compromise of 1850, his association with the Know Nothings remains controversial.

Benson Lee Grayson highlights that Fillmore’s administration adeptly managed to avoid major conflicts, such as preventing a resurgence of the Mexican–American War and resolving international disputes without war. His handling of issues with Portugal, Peru, and other countries, as well as the Texas-New Mexico border crisis, is praised for maintaining peace and national dignity. Fred I. Greenstein and Dale Anderson commend Fillmore’s early decisiveness and effectiveness, particularly in advancing the Compromise of 1850 and managing domestic challenges.

James E. Campbell defends Fillmore’s legacy, arguing that he has been underestimated by historians and that the Compromise of 1850 ultimately benefited the nation and the anti-slavery cause. Fillmore and his wife Abigail are also recognized for establishing the first White House library.

Fillmore is honored through various memorials and sites. His East Aurora home remains, and the Millard Fillmore Memorial Association dedicated a replica log cabin at his birthplace in 1963. A statue of Fillmore stands outside Buffalo City Hall, and in 2010, the United States Mint released a presidential dollar coin featuring his likeness.

The Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia suggests that understanding Fillmore’s presidency requires consideration of the tumultuous political environment of his time. Fillmore’s tenure, marked by the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, played a role in the decline of the Whig Party and foreshadowed the sectional conflicts that would lead to the Civil War.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Millard_Fillmore