President of United States The powers of the presidency have grown significantly since 1789, when George Washington became the first president. Although the level of presidential power has varied from time to time, the presidency has assumed greater prominence in American political life since the early 20th century and has already grown through Roosevelt’s New Deal programs and under George W. Bush.

Nowadays, the president is considered one of the most powerful political figures in world politics and presides over the only surviving superpower. As the top leader of the nation’s largest economy by nominal GDP, the president possesses substantial domestic and international hard and soft power. —wiki reader for virtually the entire 20th century, even for the duration of the Cold War, we thought of our president that way as “the leader of free world.”

Article II of the Constitution establishes the executive branch of the federal government, granting executive power to the president. This power includes the execution and enforcement of federal law and the authority to appoint federal executive, diplomatic, regulatory, and judicial officers. Constitutional provisions that empower the president to appoint and receive ambassadors and conclude treaties with foreign nations, along with subsequent congressional legislation, have positioned the modern presidency as the primary agent in conducting U.S.

foreign policy. This role includes overseeing the world’s most expensive military, which also possesses the second-largest nuclear arsenal.

Domestically, the president plays a central role in federal legislation and policymaking. The system of separation of powers, outlined in Article I, Section 7 of the Constitution, grants the president the authority to sign or veto federal legislation. Modern presidents are typically seen as leaders of their political parties, significantly shaping major policymaking through presidential elections.

Presidents actively promote their policy priorities to Congress members, who often rely on the president for electoral support. In recent years, presidents have increasingly used executive orders, agency regulations, and judicial appointments to influence domestic policy.

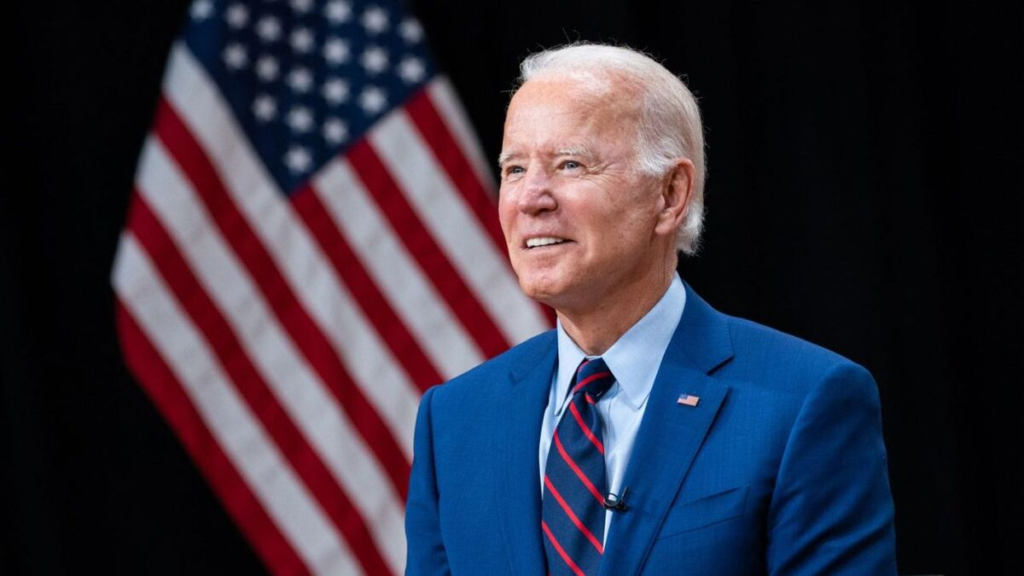

The President of United States is elected indirectly through the Electoral College for a four-year term, alongside the vice president. According to the Twenty-second Amendment, ratified in 1951, no person who has been elected to two presidential terms can be elected to a third. Additionally, nine vice presidents have ascended to the presidency due to the president’s death or resignation during their term. In total, 45 individuals have served in 46 presidencies over 58 four-year terms. Joe Biden is the 46th and current president of the United States, having assumed office on January 20, 2021.

Evolution and Growth/History and Development

Origins

During the American Revolutionary War, the Thirteen Colonies, represented by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, declared their independence from British rule. This was formalized in the Declaration of Independence, primarily authored by Thomas Jefferson and adopted unanimously on July 4, 1776. Recognizing the need for a unified effort against the British, the Continental Congress began drafting a constitution to bind the states together. After lengthy debates over representation, voting, and central government powers, the Articles of Confederation were completed in November 1777 and sent to the states for ratification.

Articles of Confederation

The Articles, which took effect on March 1, 1781, established the Congress of the Confederation as a central authority without legislative power. It could make resolutions and regulations but not laws, and it could not impose taxes or enforce commercial regulations. This design reflected how Americans believed the British system should have worked: a central body for matters concerning the entire empire, while states retained their own powers. The Congress elected a president to preside over its deliberations, a position that was largely ceremonial and different from the later office of president.

Post-Independence Challenges

In 1783, the Treaty of Paris secured independence for the former colonies, allowing the states to focus on internal affairs. By 1786, the states faced economic crises and border threats. Hard currency flowed out to pay for imports, Mediterranean commerce was threatened by North African pirates, and Revolutionary War debts remained unpaid. Civil unrest, exemplified by events like the Newburgh Conspiracy and Shays’ Rebellion, highlighted the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation.

Move Toward a Stronger Union

Following the successful resolution of disputes between Virginia and Maryland at the Mount Vernon Conference in 1785, Virginia called for a trade conference to address interstate commercial issues. The Annapolis Convention of 1786 failed due to poor attendance, but Alexander Hamilton led delegates in calling for a convention to revise the Articles. The prospects for this convention improved when James Madison and Edmund Randolph secured George Washington’s participation as a delegate for Virginia.

Constitutional Convention

When the Constitutional Convention convened in May 1787, delegates from 12 states (excluding Rhode Island) brought diverse experiences from their state governments. Most states had weak executives with limited powers, sharing authority with executive councils and countered by strong legislatures. New York was an exception, with a strong governor who had veto and appointment powers and could be re-elected indefinitely. Through closed-door negotiations, the framework for the presidency outlined in the U.S. Constitution emerged.

1789–1933

George Washington’s Presidency President of United States

George Washington, the first President of United States, set many precedents, including retiring after two terms, which alleviated fears of a monarchy. This two-term tradition lasted until 1940 and was solidified by the Twenty-Second Amendment. By the end of Washington’s presidency, political parties had formed, leading to John Adams defeating Thomas Jefferson in the first contested presidential election in 1796.

Early Political Shifts

Thomas Jefferson defeated Adams in 1800, followed by fellow Virginians James Madison and James Monroe, who each served two terms. Their dominance ended when John Quincy Adams won in 1824 after the Democratic-Republican Party split.

Jacksonian Era

Andrew Jackson’s 1828 election marked a shift, as he was outside the Virginia and Massachusetts elite. Jackson strengthened the presidency and expanded public participation. However, Martin Van Buren’s unpopularity and subsequent weak presidencies, including John Tyler’s troubled term, weakened the office.

Pre-Civil War and Senate Influence

From 1837 to 1861, eight men filled six presidential terms, with none serving two terms. The Senate, led by figures like Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun, dominated national policy until slavery debates intensified.

Lincoln and Post-Civil War

Abraham Lincoln, considered one of the greatest presidents, expanded presidential power during the Civil War. His re-election in 1864 was a first since Andrew Jackson. After Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson lost political support, and Congress remained powerful during Ulysses S. Grant’s presidency. Grover Cleveland became the first Democratic president post-war, winning two non-consecutive terms.

Early 20th Century

Theodore Roosevelt, following William McKinley’s assassination in 1901, strengthened the presidency with reforms in trust-busting, conservation, and labor. Woodrow Wilson led during World War I, but his League of Nations proposal failed in the Senate. Warren Harding’s presidency was marred by scandals, and Herbert Hoover became unpopular due to his handling of the Great Depression.

Imperial Presidency

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Impact

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, beginning in 1933, marked the rise of the “Imperial presidency.” With strong Democratic majorities in Congress and public support, his New Deal expanded the federal government and executive agencies. The presidential staff grew significantly with the creation of the Executive Office of the President in 1939, whose members do not require Senate confirmation. Roosevelt’s unprecedented third and fourth terms, World War II victory, and economic growth established the presidency as a global leadership role.

Post-War Presidencies

Harry Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower each served two terms during the Cold War, reinforcing the president’s role as “leader of the free world.” John F. Kennedy, benefiting from television’s rise, became a popular, youthful leader in the 1960s.

Congressional Reforms

Lyndon B. Johnson’s loss of support due to the Vietnam War and Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal led Congress to reassert its power. Reforms included the War Powers Resolution (1973) and the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act (1974). By 1976, Gerald Ford acknowledged Congress’s increased power, but he and his successor, Jimmy Carter, failed to win re-election. Ronald Reagan reshaped the agenda towards conservative policies, leveraging his communication skills.

Recent Trends

With the Cold War’s end, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama each served two terms. Political polarization increased, particularly after the 1994 mid-terms and the rise of Senate filibusters. Recent presidents have relied more on executive orders, regulations, and judicial appointments due to legislative gridlock. Presidential elections have mirrored this polarization, with tight popular vote margins and instances of Electoral College winners losing the popular vote.

Critics of Presidential Evolution

The Founding Fathers envisioned Congress as the dominant branch of government, with a limited executive. However, over time, presidential power has grown, leading to concerns that the modern presidency has become excessively powerful, unchecked, and reminiscent of a monarchy. Professor Dana D. Nelson argued in 2008 that presidents over the past thirty years have pursued “undivided control” over the executive branch, expanding executive powers such as executive orders and national security directives without congressional oversight. Critics like Bill Wilson of Americans for Limited Government view this expansion as a significant threat to individual freedom and democratic governance.

Congressional Authority

Article I, Section 1 of the Constitution grants Congress exclusive authority to make laws, while Article 1, Section 6, Clause 2 prohibits the president (and other executive branch officials) from serving concurrently as members of Congress. Despite this, the contemporary presidency wields substantial influence over legislation, stemming from constitutional provisions and historical shifts.

Signing and vetoing bills:

The President of United States key legislative authority lies in the Presentment Clause, granting the power to veto bills passed by Congress. While Congress can override a veto with a two-thirds majority vote, this is often challenging. Originally designed to prevent a “tyranny of the majority,” the veto has evolved into a tool for presidents to address policy disagreements with legislation, shaping the modern legislative process significantly.

Under the Presentment Clause, the president has three options when presented with a bill: signing it into law, vetoing it and returning it to Congress with objections, or taking no action. The Line-Item Veto Act of 1996 aimed to enhance presidential veto power by allowing selective spending item removal. However, the Supreme Court deemed it unconstitutional in Clinton v. City of New York (1998). President of United States

Setting the agenda:

Throughout history, presidential candidates have campaigned with promised legislative agendas, as mandated by Article II, section 3, Clause 2, which requires the president to recommend necessary measures to Congress. This recommendation typically occurs through the State of the Union address, outlining legislative proposals for the upcoming year, along with other formal and informal communications.

Presidents can shape legislation by suggesting, requesting, or insisting on specific laws. They also exert influence during the legislative process by engaging with individual members of Congress. While the Constitution doesn’t specify who can write legislation, only Congress members can introduce bills, limiting the president’s legislative power.

Drafting Legislation and Influencing Congress:

The President of United States and executive branch officials may draft legislation and urge members of Congress to introduce it. Additionally, the president can leverage the threat of veto to influence proposed legislation.

Promulgating Regulations:

Congress often delegates implementation powers to federal agencies, allowing presidents to control agencies that issue regulations with minimal congressional oversight. Critics argue that this has led to an overreach of executive power, with presidents criticized for appointing unaccountable policy “czars” and issuing unconstitutional signing statements.

Convening and Adjourning Congress:

The President of United States can call special sessions of Congress in times of crisis, a power used infrequently since John Adams. Before the Twentieth Amendment, presidents routinely called the Senate to confirm nominations or ratify treaties. However, this power is rarely exercised today, as Congress remains in session year-round, holding pro forma sessions to prevent adjournment disagreements. The president also has the authority to adjourn Congress if the House and Senate cannot agree, although this power has never been used.

Presidential Authority

Administrative Powers:

Presidents of United States wield significant authority in appointing thousands of political positions, including ambassadors and Cabinet members, subject to Senate confirmation. While they can typically dismiss executive officials at will, Congress may restrict this power for specific roles.

To oversee the federal bureaucracy, presidents establish layers of staff within the Executive Office of the President, primarily based in the White House. They also issue directives like proclamations and executive orders to manage government operations. However, these directives are subject to judicial review and can be overturned by Congress through legislation.

Foreign Affairs:

The President of United States plays a pivotal role in foreign affairs, with the Constitution granting broad powers in this realm. The President of United States can receive ambassadors, appoint U.S. ambassadors, and negotiate agreements with other nations, subject to Senate approval. Technological advancements have expanded presidential influence, with direct meetings between presidents and foreign leaders becoming common.

Commander-in-Chief:

As commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces, the president holds significant authority over military matters. While Congress has the power to declare war, the president directs military operations. However, the extent of this authority has been debated throughout history, with Congress providing oversight through mechanisms like the War Powers Resolution. Despite this, presidents have historically initiated military actions, although some conflicts have occurred without official declarations of war. Operational command of the military is typically delegated to the Department of Defense, overseen by the secretary of defense and Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Legal Authority and Privileges

Presidential Authority and Privileges

The President of United States holds the power to nominate federal judges, including those for the Supreme Court and courts of appeals, but Senate confirmation is required. This process can be challenging, particularly if the Senate opposes the president’s ideological stance. Additionally, the president may grant pardons and reprieves, often controversially, especially when done near the end of a term.

Two doctrines, executive privilege and state secrets privilege, afford the president a degree of autonomy in exercising executive power. Executive privilege allows the president to withhold certain communications from disclosure, while the state secrets privilege permits withholding information in legal proceedings to protect national security. Critics argue that these privileges may be misused to conceal government actions.

The extent of the President of United States immunity from court cases is debated. While Nixon v. Fitzgerald (1982) shielded former President Nixon from a civil lawsuit related to his official actions, Clinton v. Jones (1997) determined that a sitting president is not immune from civil suits for pre-presidential actions. Legal battles over access to personal tax returns and potential indictments of former presidents continue to unfold.

Executive Responsibilities

Head of state

As head of state, the President of United States serves as the face of the United States, representing the government to its citizens and the world. This role includes hosting formal events like State Arrival Ceremonies and state dinners for foreign dignitaries. In addition to these official duties, presidents engage in less formal traditions such as throwing out the ceremonial first pitch at baseball games or participating in holiday events like the White House egg rolling. They also play a key role in presidential transitions by offering advice to their successors and leaving personal messages in the Oval Office on Inauguration Day.

Head of party

The modern presidency often portrays the president as a prominent figure, akin to a celebrity, with images of the office carefully crafted by PR officials and presidents themselves. Critics argue this creates a “propagandized leadership” with a captivating aura. Some even suggest that unrealistic expectations are placed on presidents by voters, expecting them to excel in various roles from economic stewardship to global leadership.

Global leader

As the head of their political party, the President of United States performance heavily influences their party’s electoral success, impacting candidates at all levels of government. While they are typically seen as a global leader due to the United States’ superpower status and strong international ties, tensions can arise between the president and their party, especially if support wanes among party members in Congress.

Choosing a Leader

Presidential Eligibility

Article II, Section 1, Clause 5 of the Constitution outlines three prerequisites for presidency: being a natural-born U.S. citizen, at least 35 years of age, and having lived in the U.S. for a minimum of 14 years. Despite meeting these criteria, disqualification can occur under various circumstances:

- Article I, Section 3, Clause 7 allows disqualification for individuals impeached, convicted, and barred from public office. While its applicability to the presidency is debated, past disqualifications have been limited to federal judges.

- Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits individuals who swore allegiance to the Constitution but later rebelled against the U.S. This disqualification can be overturned by a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress, despite uncertainties over its direct application to the presidency.

- The Twenty-second Amendment restricts presidency to two terms and stipulates that if someone serves over two years of another’s term, they can only be elected president once.

Campaigning and Nomination

The modern presidential campaign kicks off before primary elections, where major political parties narrow down their candidates before national nominating conventions. At these conventions, the most successful candidate becomes the party’s presidential nominee, often selecting a vice-presidential nominee, too. Nominees engage in nationally televised debates, sometimes including third-party candidates. They traverse the country, articulating their views, wooing voters, and seeking donations. Much emphasis is placed on winning swing states through frequent visits and mass media advertising.

Election

The president is indirectly elected by voters in each state and the District of Columbia through the Electoral College, a body of electors convened every four years solely for this purpose. Each state is allocated a number of electors based on its congressional representation. The Twenty-third Amendment extends this to the District of Columbia. Currently, most states follow a winner-takes-all system, awarding all electors to the party with a plurality of votes. Maine and Nebraska have a different approach, allocating electors based on both statewide and district-wide outcomes.

Electoral Process

On the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December, approximately six weeks after the election, electors gather in their respective state capitals (and in Washington, D.C.) to cast their votes for president and vice president. While not mandated by the Constitution, many states have laws requiring electors to vote for their pledged candidates. The votes are then sent to Congress, which counts them in a joint session held in early January.

If a candidate secures an absolute majority of electoral votes (currently 270 out of 538), they are declared the winner. Otherwise, a contingent election is held in the House of Representatives, where each state delegation casts a single vote, and the top three candidates compete. The winner must secure the votes of an absolute majority of states (currently 26 out of 50).

Inauguration

According to the Twentieth Amendment, the president and vice president’s four-year term begins at noon on January 20 following the election. This date, known as Inauguration Day, was changed from March 4 by the amendment. Before assuming office, the president recites the presidential Oath of Office, pledging to faithfully execute the duties of the presidency and preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution. Traditionally, the oath is administered by the chief justice of the United States, with the president placing one hand on a Bible and adding “So help me God” at the end.

Incumbency

Presidential Term Limits

When George Washington declined to run for a third term and Thomas Jefferson later embraced the principle of “two terms then out,” a tradition was established. This tradition solidified with subsequent presidents like James Madison and James Monroe. However, Ulysses S. Grant attempted to break this tradition by seeking nomination for a non-consecutive third term in 1880 but was unsuccessful.

In 1940, Franklin Roosevelt was elected to a third term, deviating from the longstanding precedent. He was re-elected again in 1944 but died shortly into his fourth term. In response to Roosevelt’s extended presidency, the Twenty-second Amendment was ratified in 1951, limiting presidents to two terms, or one if they served more than two years of another president’s term. Since then, this amendment has applied to six twice-elected presidents: Dwight D. Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama.

Vacancies and Succession

The Twenty-fifth Amendment, ratified in 1967, clarified the process of presidential succession. It stipulates that the vice President of United States becomes president in the event of the president’s removal, death, or resignation. Before this amendment, there was ambiguity about whether the vice president would assume the presidency or simply act as president. The Presidential Succession Act of 1947 outlines the line of succession, which includes the speaker of the House, president pro tempore of the Senate, and eligible heads of federal executive departments. No statutory successor has yet been called upon to act as president.

Temporary Transfers of Power

According to the Twenty-fifth Amendment, the president can temporarily transfer presidential powers and duties to the vice president, who then becomes acting president, by sending a statement to the speaker of the House and the president pro tempore of the Senate, declaring an inability to discharge duties. The president resumes powers upon transmitting a second declaration stating readiness. Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Joe Biden have utilized this mechanism, each anticipating surgery.

The amendment also allows the vice President of United States , with a majority of certain Cabinet members, to transfer presidential powers to the vice president by transmitting a written declaration to congressional leaders, declaring the president’s inability to discharge duties. If the president denies inability, powers are resumed unless the vice president and Cabinet make a second declaration, leaving Congress to decide.

Removal Procedures

Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution permits the removal of high federal officials, including the president, for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors”. The House of Representatives has the power to impeach officials by majority vote, while the Senate serves as a court with the power to remove impeached officials by a two-thirds vote to convict.

Three presidents—Andrew Johnson, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump—have been impeached by the House, but none convicted by the Senate. Richard Nixon faced impeachment inquiry but resigned before the House voted on it.

Circumvention of Authority

Measures short of removal have been taken to address perceived recklessness or disability in the president. Staff sometimes fail to deliver messages to or from the president to avoid executing certain orders, such as during Richard Nixon’s tenure due to his heavy drinking. In 1919, Woodrow Wilson’s partial incapacitation from a stroke led to controversy, with his wife serving as gatekeeper for access to him, managing paperwork and information flow.

Presidential Compensation

The salary of the President of United States has a long history of adjustments. Initially established at $25,000 in 1789, it has seen several increases over time. By 2001, it had reached $400,000 annually, accompanied by a $50,000 expense allowance, a $100,000 nontaxable travel account, and a $19,000 entertainment account. This salary, along with its allowances, is determined by Congress and cannot be altered during a presidential term according to constitutional provisions.

Official Residences

The White House in Washington, D.C., chosen by George Washington and constructed starting in 1792, has served as the primary residence for every president since John Adams. Previously referred to as the “President’s Palace” or the “Executive Mansion,” it was formally named the White House by Theodore Roosevelt in 1901. While the federal government covers expenses for state functions, the president is responsible for personal and family expenses, including dry cleaning and food.

Camp David, located in Maryland’s Frederick County, functions as the president’s country retreat. Providing a serene environment, it has been utilized for hosting foreign dignitaries since the 1940s.

Additionally, the President’s Guest House, situated near the White House Complex, serves as the official guest house. Comprising four interconnected houses, it offers secondary residence options for the president if necessary.

Travel Arrangements

Long-distance air travel for the President of United States primarily relies on two customized Boeing VC-25 aircraft, known as Air Force One during presidential flights. One plane is typically used for domestic trips, while both are employed for international travel, with one serving as the primary aircraft and the other as a backup. In instances where large aircraft cannot land, smaller Air Force planes like the Boeing C-32 are utilized. Civilian flights with the president aboard are designated Executive One.

For short-distance air travel, a fleet of U.S. Marine Corps helicopters is available, known as Marine One when transporting the president. Typically, multiple helicopters fly together, frequently switching positions to obscure which one carries the president, enhancing security.

Ground transportation involves the use of the presidential state car, an armored limousine resembling a Cadillac sedan but built on a truck chassis. Operated and maintained by the U.S. Secret Service, this vehicle ensures the president’s safety. Additionally, armored motorcoaches are available for touring trips.

Security Measures

The U.S. Secret Service bears the responsibility of safeguarding the president and the first family. To enhance security, Secret Service codenames are assigned to the president, first lady, their children, other immediate family members, as well as prominent persons and locations. Initially utilized for security in the absence of encrypted electronic communications, these codenames now serve for the sake of brevity, clarity, and tradition.

Post-presidency

Post-Presidential Activities

Several former presidents have pursued notable careers following their time in office. William Howard Taft notably served as chief justice of the United States, while Herbert Hoover contributed to government reorganization efforts post-World War II. Grover Cleveland, despite a failed reelection bid in 1888, reclaimed the presidency in 1892. Notable post-presidential congressional service includes John Quincy Adams’ 17-year tenure in the House of Representatives and Andrew Johnson’s brief return to the Senate before his passing.

Certain ex-President of United States have remained highly active, particularly in international affairs. Theodore Roosevelt, Herbert Hoover, Richard Nixon, and Jimmy Carter notably engaged in global diplomacy and humanitarian efforts. Presidents may also leverage their predecessors as envoys for private messages or official U.S. representation at foreign events and state funerals.

Former presidents often retain political involvement. Bill Clinton, for instance, supported his wife Hillary’s presidential bids and aided President Obama’s reelection campaign. Similarly, Obama collaborated with Vice President Joe Biden for his 2020 campaign. Donald Trump has maintained a media presence and appeared at various events since leaving office.

Pension and Benefits

The Former Presidents Act (FPA), established in 1958, extends lifelong benefits to former presidents and their spouses, including a monthly pension, healthcare in military facilities, insurance, and Secret Service protection. Congressional amendments have increased presidential pensions and staff allowances. Former presidents also receive travel funds and franking privileges.

Initially, ex-President of United States received no federal assistance until the FPA’s enactment. The pension, subject to congressional approval, is based on cabinet secretaries’ current administration salaries. Former presidents who served in Congress may also collect congressional pensions.

Former presidents, their spouses, and children under 16 were once protected by the Secret Service until the president’s death, but legislation in 1997 limited this protection to 10 years post-office. However, a 2013 law reinstated lifetime Secret Service protection for presidents Obama, George W. Bush, and subsequent presidents, excluding first spouses who remarry.

Presidential Archives

Since Herbert Hoover’s tenure, every president has established a dedicated repository called a presidential archive to safeguard and provide access to their papers, records, and related materials. Completed archives are entrusted to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), with initial funding sourced from private, non-federal entities. Currently, there are thirteen presidential archives in the NARA system.

Additionally, there are presidential archives managed by state governments, private foundations, and universities. For example:

- The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, overseen by the State of Illinois

- The George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, operated by Southern Methodist University

- The George H. W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, administered by Texas A&M University

- The Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum, managed by the University of Texas at Austin

Several former presidents have been actively involved in the establishment of their own archives, with some even arranging for their final resting place at these sites. Notably, some presidential archives also serve as the burial grounds for the President of United States they commemorate. For instance:

- The Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Independence, Missouri

- The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, and Boyhood Home in Abilene, Kansas

- The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, California

- The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in Simi Valley, California

These burial sites are accessible to the public for visitation.