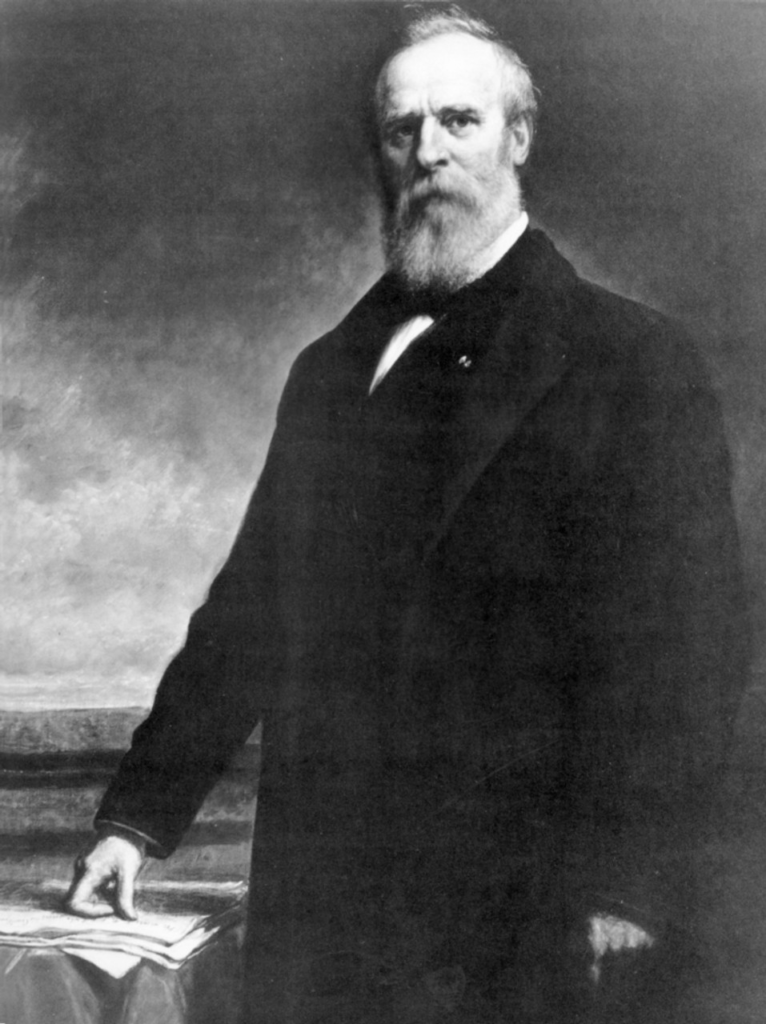

Rutherford B. Hayes, the 19th President of the United States, is often remembered as a leader who navigated one of the most tumultuous periods in American history. Born on October 4, 1822, in Delaware, Ohio, Hayes grew up in a family that valued education and hard work. His father died before he was born, leaving his mother, Sophia Birchard Hayes, to raise Rutherford and his siblings. Despite this challenge, she instilled in him a strong sense of responsibility and a commitment to public service, values that would shape his future political career.

Rutherford B. Hayes attended Kenyon College in Ohio and later studied law at Harvard Law School, where he gained a reputation for his sharp intellect and dedication to justice. After completing his education, he returned to Ohio and began practicing law in Cincinnati, where he became involved in politics and gained a reputation as a reform-minded attorney.

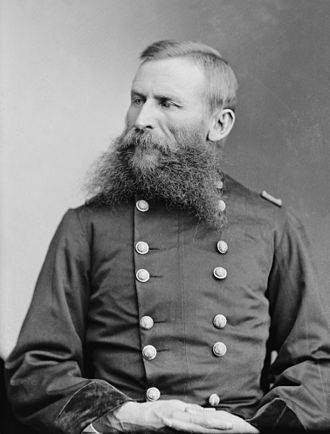

During the Civil War, Rutherford B. Hayes demonstrated his leadership on the battlefield. Despite being wounded multiple times, he continued to serve with distinction, earning the respect of his peers. By the end of the war, he had risen to the rank of brevet major general. This military service significantly boosted his political career, as he was seen as a war hero dedicated to preserving the Union.

Rutherford B. Hayes entered politics as a member of the Republican Party, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor of Ohio. As governor, he focused on issues such as education reform, civil service reform, and efforts to support the rights of African Americans, reflecting his commitment to progressive policies.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

- 13th President of the United States

- 14th President of the United States

- 15th President of the United States

- 16th President of the United States

- 17th President of the United States

- 18th President of the United States

- 19th President of the United States

The presidential election of 1876 was one of the most contentious in American history. Rutherford B. Hayes ran against Democrat Samuel J. Tilden in a race marked by accusations of voter fraud and political manipulation. Although Tilden won the popular vote, the results in several states were disputed, leading to a constitutional crisis. Ultimately, a special electoral commission awarded Hayes the presidency by just one electoral vote, a decision that became known as the Compromise of 1877.

The Compromise of 1877 was a critical moment in American history. In exchange for Rutherford B. Hayes becoming president, he agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction. This decision had profound consequences for African Americans in the South, as it allowed Southern states to implement discriminatory laws that disenfranchised Black voters and institutionalized segregation. Despite these negative outcomes, Hayes believed that national reconciliation was necessary to heal the divisions caused by the Civil War.

During his presidency, Hayes focused on civil service reform and restoring trust in the federal government. He attempted to end the spoils system, which awarded government jobs based on political loyalty rather than merit. Although he faced significant opposition, Rutherford B. Hayes laid the groundwork for future reforms that would professionalize the federal bureaucracy.

Rutherford B. Hayes was also a strong advocate for education, particularly in the South, where he believed education was key to the nation’s future. He supported measures to improve public schools and access to education for all Americans, regardless of race.

One of the lesser-known aspects of Rutherford B. Hayes presidency was his interest in foreign policy. He sought to expand American influence in Latin America and Asia while avoiding military conflict. His administration oversaw the construction of new naval ships and laid the groundwork for a more modern and powerful U.S. Navy.

After serving one term, Rutherford B. Hayes chose not to seek re-election, staying true to his promise not to run for a second term. He retired to his home in Ohio, where he remained active in public life, particularly in the fields of education and veterans’ affairs. Rutherford B. Hayes served as a trustee of several educational institutions and worked to improve the quality of education across the country. He also became a vocal advocate for veterans’ rights, particularly those who had served in the Civil War.

Rutherford B. Hayes passed away on January 17, 1893, leaving behind a mixed legacy. While he is often criticized for the Compromise of 1877 and its impact on Reconstruction, his efforts to reform the civil service and promote education have earned him respect among historians. His presidency represents a turning point in American history, as the nation moved from the challenges of Reconstruction toward the industrial age.

Rutherford B. Rutherford B. Hayes’ life and career reflect the complexities of the post-Civil War era. He was a man of principle who sought to bring about positive change in a divided nation. Though his presidency had its shortcomings, his dedication to public service and his commitment to reform left a lasting impact on the United States.

Early Life and Family: The Roots of Rutherford B. Hayes

A Childhood Marked by Family Bonds

Rutherford Birchard Rutherford B. Hayes entered the world on October 4, 1822, in Delaware, Ohio, but his birth was shadowed by loss. His father, Rutherford Ezekiel Hayes, Jr., a Vermont storekeeper who had moved his family to Ohio in 1817, passed away ten weeks before Rutherford’s birth. Left a widow, his mother, Sophia Birchard Hayes, took on the responsibility of raising Rutherford and his sister, Fanny, the only two of her four children to survive to adulthood.

Although she never remarried, Sophia found support from her younger brother, Sardis Birchard, who lived with the family for a time and became a father figure to Rutherford. Sardis played a significant role in his nephew’s early education and remained a constant presence in his life.

Ancestry and Heritage

Rutherford Hayes’ family tree was firmly rooted in New England. Both his parents descended from early New England settlers, with the Hayes family originating in Scotland before settling in Connecticut. His great-grandfather, Ezekiel Hayes, served as a militia captain in the American Revolutionary War, but Ezekiel’s son (Rutherford’s grandfather) relocated to Vermont for safety during the conflict. Rutherford’s mother’s ancestors also made Vermont their home. Though Rutherford B. Hayes considered himself of Scottish descent, his heritage was a mix of many European backgrounds. In a reflection on his lineage, Hayes noted that, out of his thirty ancestors who emigrated to America, only two—Hayes and Rutherford—were of Scottish descent.

Though much of his extended family stayed in Vermont, they remained connected. John Noyes, a relative by marriage, had been his father’s business partner and later became a Congressman. Additionally, Hayes’ first cousin, Mary Jane Mead, was the mother of the renowned sculptor Larkin Goldsmith Mead and architect William Rutherford Mead. Hayes was also related to John Humphrey Noyes, the founder of the Oneida Community. These family connections kept his ties to New England strong, even as he made his mark in Ohio.

Education and Early Law Career: Laying the Foundation for Success

Early Education and Academic Achievements

Rutherford B. Hayes began his education at local schools in Delaware, Ohio, before moving on to the Methodist Norwalk Seminary in Norwalk, Ohio, in 1836. He performed well academically and transferred to the Webb School, a preparatory institution in Middletown, Connecticut, where he studied Latin and Ancient Greek. After returning to Ohio in 1838, Hayes enrolled at Kenyon College in Gambier, where he thrived both academically and socially. He joined various student societies and became involved in Whig politics. Graduating in 1842 with the highest honors, Hayes was named valedictorian of his class and became a member of the prestigious Phi Beta Kappa honor society.

Entering the Legal Profession

After a brief stint reading law in Columbus, Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes moved to the East Coast to attend Harvard Law School in 1843. He graduated in 1845 with a law degree and was admitted to the Ohio bar that same year. Hayes then opened a law office in Lower Sandusky (now Fremont). Although his business was slow at first, Hayes persisted, representing his uncle Sardis in real estate cases and gradually building his client base.

In 1847, Rutherford B. Hayes faced a health scare when his doctor suspected he had tuberculosis. Considering a change of climate, Hayes thought about joining the Mexican-American War but ultimately opted to visit family in New England instead. After his return, he and his uncle Sardis embarked on a long trip to Texas, where Hayes reconnected with his college friend, Guy M. Bryan. Despite these adventures, business remained slow in Lower Sandusky, prompting Hayes to make a significant move to Cincinnati.

Cincinnati Law Practice and Marriage: Building a Family and a Career

A New Chapter in Cincinnati

In 1850, Rutherford B. Hayes relocated to Cincinnati, where he opened a law practice with John W. Herron, a fellow lawyer from Chillicothe. Later, Rutherford B. Hayes partnered with William K. Rogers and Richard M. Corwine, finding much more success in Cincinnati than he had in Lower Sandusky. He quickly integrated into the city’s social scene, joining the Cincinnati Literary Society and the Odd Fellows Club. He also attended the Episcopal Church, although he never became a formal member.

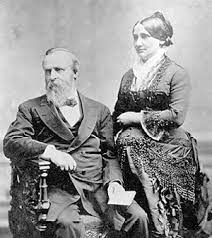

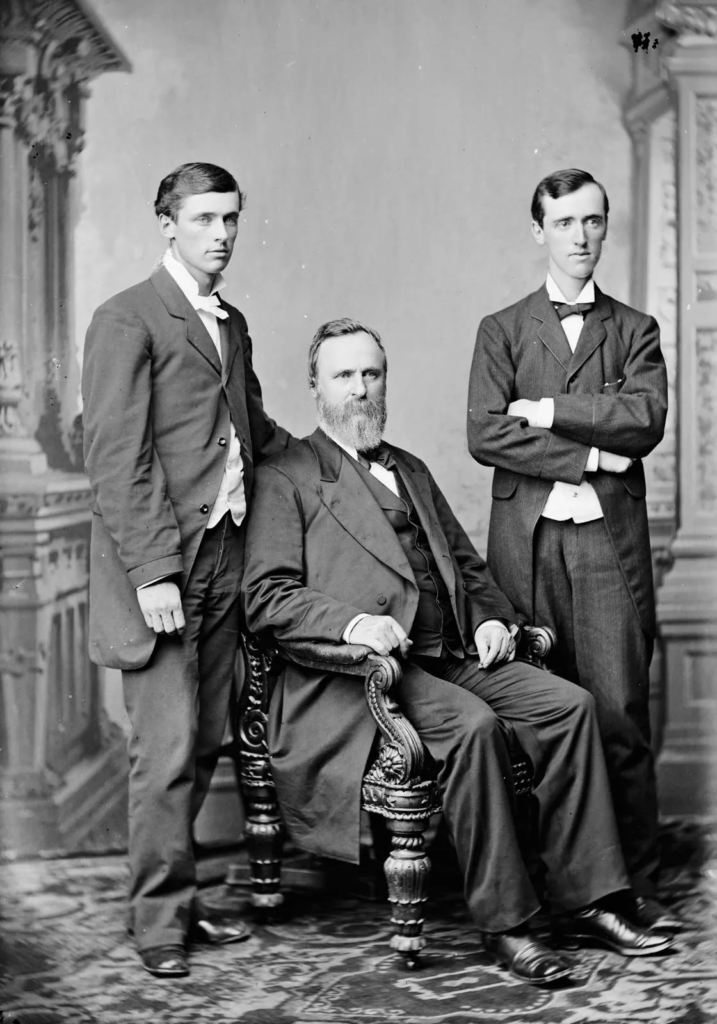

Marriage and Family Life

During his time in Cincinnati, Rutherford B. Hayes began courting Lucy Webb, a young woman his mother had encouraged him to meet years earlier. Initially, Hayes thought Lucy was too young, but over time, they grew closer. They became engaged in 1851 and were married on December 30, 1852, at Lucy’s mother’s home. Over the next several years, the couple welcomed three sons: Birchard Austin in 1853, Webb Cook in 1856, and Rutherford Platt in 1858.

Lucy Hayes was a devout Methodist, a dedicated abolitionist, and a strong advocate of temperance. Her beliefs influenced her husband, particularly in his political and social views, although Hayes never officially joined her church. Lucy’s convictions would continue to shape Rutherford’s perspectives throughout his life.

Rising in the Cincinnati Legal Community

Rutherford B. Hayes initially focused on commercial law, but his reputation grew as a skilled criminal defense attorney. He successfully defended several clients accused of murder, including one notable case where he used an early form of the insanity defense to save a woman from execution; instead, she was committed to a mental institution. In addition to his work in criminal law, Hayes also represented escaped slaves under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Cincinnati, being close to the slave state of Kentucky, saw many such cases, and Hayes’ abolitionist beliefs made this work particularly meaningful to him. His involvement in these cases helped raise his profile in the Republican Party and contributed to his growing political reputation.

Rutherford B. Hayes ‘ legal success translated into political opportunities. Although he declined a Republican nomination for a judgeship in 1856, he was soon called upon again to serve. In 1858, when a vacancy opened for the position of city solicitor, Hayes was elected by the city council to fill the role. He was re-elected to a full term in 1859, winning by a significant margin, further solidifying his standing in Cincinnati’s legal and political circles.

The Civil War: Rutherford B. Hayes’ Journey from Doubt to Leadership

Initial Hesitations and Early Actions

As the Southern states began to secede following Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, Rutherford B. Hayes found himself uncertain about the prospect of war. He questioned whether the Union could truly be restored by force, even suggesting that perhaps the two sides were irreconcilable and should part ways. When he said, “Let them go,” it reflected his initial hesitation. In Cincinnati, where many residents hailed from the Southern states, the political atmosphere turned against the Republican Party. The city’s elections in April 1861 saw Democrats and Know-Nothings combine forces, leading to Hayes losing his position as city solicitor.

Shortly after this, Rutherford B. Hayes returned to private law practice, forming a brief partnership with Leopold Markbreit that lasted just three days before the war’s outbreak. The firing on Fort Sumter shifted Hayes’ perspective entirely. His doubts were resolved, and he joined a volunteer company made up of his friends from the Cincinnati Literary Society. Governor William Dennison quickly appointed some of these volunteers to the 23rd Regiment of Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Hayes was promoted to major, alongside his friend Stanley Matthews as lieutenant colonel. Among the ranks was a young private named William McKinley, a future U.S. president.

Western Virginia Campaigns and the Battle of South Mountain

After a month of training, Hayes and the 23rd Ohio set off for western Virginia in July 1861 as part of the Kanawha Division. Their first encounter with Confederate forces occurred in September at the Battle of Carnifex Ferry in what is now West Virginia. The Union troops successfully pushed back the Confederates, marking Hayes’ early involvement in the war. By November, Hayes had been promoted to lieutenant colonel as Matthews moved on to command another regiment. Throughout the winter, Hayes led his men deeper into western Virginia.

With spring came renewed action. Rutherford B. Hayes led several raids against Confederate positions, sustaining a minor knee injury during one of these engagements. By September 1862, his regiment was called east to reinforce General John Pope’s Army of Virginia at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Unfortunately, they arrived too late for the battle, but joined the Army of the Potomac in their pursuit of Robert E. Lee’s forces advancing into Maryland.

Rutherford B. Hayes and the 23rd Ohio spearheaded the Union advance at the Battle of South Mountain on September 14. Leading a charge against an entrenched Confederate position, Hayes was shot through the left arm, fracturing the bone. Despite his injury, he managed to have a handkerchief tied above the wound to slow the bleeding and continued to lead his men. Even when he ordered a defensive action while resting, Hayes remained determined. Eventually, his men brought him back behind the lines, and he was taken to a hospital.

While the regiment moved on to Antietam, Hayes was sidelined for the rest of the campaign. However, his bravery didn’t go unnoticed. In October, he was promoted to colonel and given command of the first brigade of the Kanawha Division as a brevet brigadier general.

Commanding in the Shenandoah Valley

The winter and spring of 1863 passed quietly for Rutherford B. Hayes and his division near Charleston, Virginia (now West Virginia). Action resumed in July when they clashed with John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry at the Battle of Buffington Island. Afterward, Hayes focused on encouraging the men of the 23rd Ohio to reenlist, which many did. As 1864 began, the command structure in West Virginia was reorganized, placing Hayes’ division under General George Crook’s Army of West Virginia. They advanced into southwestern Virginia, where they destroyed vital Confederate salt and lead mines.

On May 9, 1864, Hayes and his brigade engaged Confederate forces at Cloyd’s Mountain. Hayes led a successful charge that drove the enemy from their entrenched positions. Following the battle, Union forces destroyed Confederate supplies and continued to engage in skirmishes, keeping the pressure on the rebels.

The next chapter of Rutherford B. Hayes’ military service took him to the Shenandoah Valley for the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Crook’s corps joined Major General David Hunter’s Army of the Shenandoah, quickly coming into contact with Confederate forces. They captured Lexington, Virginia, on June 11, and advanced south, tearing up railroad tracks as they went. However, when they reached Lynchburg, Hunter hesitated, fearing the Confederate forces were too strong. Hayes, frustrated with the lack of aggression, later wrote that General Crook would have succeeded in taking Lynchburg. But before they could attempt another assault, Confederate General Jubal Early’s raid into Maryland forced them to retreat northward.

In late July, Early’s forces surprised Hayes and his men at the Battle of Kernstown. Hayes was slightly wounded by a bullet to the shoulder and lost his horse during the battle. Despite these setbacks, his leadership remained strong, though the Union army was defeated in the engagement. After retreating to Maryland, the army was reorganized once more, with Major General Philip Sheridan replacing Hunter.

By August, the tide was turning again. Early’s army retreated up the Shenandoah Valley, pursued by Sheridan. Rutherford B. Hayes’ brigade played a key role in several engagements, fending off Confederate attacks at Berryville and breaking enemy lines at Opequon Creek. The Union forces followed these victories with another triumph at Fisher’s Hill on September 22 and a final success at Cedar Creek on October 19. During the Battle of Cedar Creek, Hayes suffered a sprained ankle after being thrown from his horse and was struck in the head by a spent bullet, though he avoided serious injury.

Recognition and Final Victory

Rutherford B. Hayes’ courage and leadership in these battles earned him significant recognition. Ulysses S. Grant, the Union’s commanding general, praised Hayes for his conduct, noting that his bravery on the field was marked by more than just personal daring; Hayes demonstrated qualities of higher leadership. By October 1864, Hayes was promoted to brigadier general, and soon after, he was brevetted major general for his contributions.

During this period, Rutherford B. Hayes also received joyful news from home. His fourth son, George Crook Rutherford B. Hayes, was born, named in honor of Hayes’ commander. As winter set in, the army prepared for what would be their final season of conflict. With General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox in April 1865, the Civil War came to a close. Hayes visited Washington, D.C., in May to witness the Grand Review of the Armies, a celebration of the Union’s victory. Shortly after, he and the 23rd Ohio returned home to Ohio, where they were formally mustered out of service.

Post-War Politics

U.S. Representative from Ohio

In 1864, while serving with the Army of the Shenandoah, Rutherford B. Hayes was nominated by the Republican Party to represent Ohio’s 2nd congressional district in the House of Representatives. Despite pressure from friends in Cincinnati to leave his military post and campaign, Hayes refused. He believed that an officer who would abandon his duty for electioneering was unworthy of his position. Instead, Hayes chose to write letters to voters explaining his stance on various issues. His approach proved effective, as he won the election by a margin of 2,400 votes against the incumbent Democrat, Alexander Long.

Democratic President Andrew Johnson and Radical Republicans

When the 39th Congress convened in December 1865, Rutherford B. Hayes joined a sizable Republican majority. While he aligned with the party’s moderate wing, he was willing to support the more radical elements to maintain party unity. The key legislative focus during this period was the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Hayes supported the amendment, which passed both houses of Congress in June 1866. His views on Reconstruction mirrored those of his fellow Republicans: he believed that the South should be reintegrated into the Union with proper safeguards for freedmen and other black southerners.

In contrast, President Andrew Johnson, who took office after Lincoln’s assassination, sought to quickly reintegrate the seceded states without demanding strong protections for the newly freed slaves. Johnson’s lenient approach included granting pardons to many prominent former Confederates, which Hayes and many congressional Republicans opposed. They worked to counter Johnson’s plan by supporting the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

Reelected in 1866, Hayes returned to Congress during a lame-duck session. On January 7, 1867, he cast his vote in favor of the resolution that initiated the first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson. He also supported the Tenure of Office Act, which restricted Johnson’s ability to remove administration officials without Senate approval, and advocated for a civil service reform bill, although it did not pass. Hayes continued to support Reconstruction policies but resigned in July 1867 to pursue the governorship of Ohio.

Governor of Ohio

As a popular Congressman and former Army officer, Hayes was seen as a strong candidate for the Ohio governorship in 1867. Although his political views were more moderate than the Republican Party’s platform, he supported an amendment to the Ohio state constitution that would guarantee voting rights for black men. His opponent, Allen G. Thurman, made opposition to this amendment a focal point of his campaign. Despite a vigorous campaign on both sides, the amendment failed, and Democrats gained control of the state legislature. Rutherford B. Hayes initially feared he had lost, but the final count revealed he won the election by 2,983 votes out of 484,603 cast.

During his tenure as governor, Rutherford B. Hayes had a limited role due to Ohio’s lack of gubernatorial veto power. Nevertheless, he managed to oversee the creation of a school for deaf-mutes and a reform school for girls. He also supported the impeachment of President Johnson, which ultimately failed by a single vote in the Senate. Reelected in 1869, Hayes continued to advocate for black suffrage and successfully associated his opponent, George H.

Pendleton, with Confederate sympathies. His second term was more productive, with advancements in suffrage and the establishment of a state Agricultural and Mechanical College, which later became Ohio State University. Hayes also proposed reducing state taxes and reforming the state prison system. Choosing not to seek a third term, he looked forward to retiring from politics in 1872.

Private Life and Return to Politics

As Rutherford B. Hayes prepared to leave office, some reform-minded Republicans urged him to run for the U.S. Senate against the incumbent Republican, John Sherman. Hayes declined, preferring to retire from public life and spend time with his family. He focused on promoting railway extensions to his hometown of Fremont and managed real estate in Duluth, Minnesota. Although he hoped for a cabinet position, he was only offered an assistant U.S. treasurer role in Cincinnati, which he declined. Hayes also accepted a nomination for his old House seat in 1872 but lost the election to Henry B. Banning.

In 1873, Rutherford B. Hayes wife Lucy gave birth to another son, Manning Force Hayes. The same year, the Panic of 1873 affected businesses nationwide, including Hayes’s. After the death of his uncle Sardis Birchard, Hayes moved his family into Spiegel Grove, a grand house his uncle had built for them. Hayes also announced his uncle’s bequest of $50,000 to fund a public library for Fremont, which opened in 1874 and was later expanded in 1878. Hayes served as chairman of the library’s board of trustees until his death.

Despite his initial desire to avoid politics, Hayes was nominated for governor again in 1875. His campaign focused on Protestant concerns about potential state aid to Catholic schools. Although not personally anti-Catholic, he used anti-Catholic sentiment to rally support. His campaign succeeded, and Rutherford B. Hayes was re-elected as governor on October 12, 1875, by a significant margin. As the first person to serve three terms as governor of Ohio, he reduced state debt, reestablished the Board of Charities, and repealed the Gaghan Bill, which had allowed Catholic priests to be appointed to schools and penitentiaries.

Election of 1876

Republican Nomination and Campaign Against Tilden

Rutherford B. Hayes impressive record in Ohio elevated him as a leading contender for the presidency in 1876. At the 1876 Republican National Convention, the Ohio delegation was firmly behind him, with Senator John Sherman working tirelessly to secure Hayes’s nomination. The initial favorite, James G. Blaine of Maine, started with a significant delegate lead but failed to achieve a majority. As Blaine’s support dwindled, delegates turned to Hayes, who secured the nomination on the seventh ballot. Representative William A. Wheeler from New York was selected as his vice-presidential running mate—a choice that Hayes had recently remarked, “I am ashamed to say: who is Wheeler?”

The Hayes-Wheeler campaign focused on appealing to the Southern Whigs, aiming to attract former Southern Whigs away from the Democrats. Hayes and Wheeler, in contrast to their Democratic opponents, were perceived as advocating for the protection of black civil rights, though their campaign rhetoric was less direct on this issue compared to Tilden’s.

The Democratic nominee, Samuel J. Tilden, was the governor of New York and was considered a formidable opponent. Like Rutherford B. Hayes, Tilden was known for his integrity and supported civil service reform. The campaign, largely managed by surrogates, saw Hayes and Tilden remaining in their respective hometowns due to the economic downturn, which made the incumbent party unpopular. Both candidates concentrated their efforts on swing states and the South, where Reconstruction Republican governments faced severe challenges, including efforts to suppress freedman voting.

Election Day returns showed a tight race, with Tilden winning the popular vote and securing 184 electoral votes. Hayes, meanwhile, appeared to have 166 electoral votes with the results from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina remaining contested. The results in these states were disputed due to allegations of fraud and voter suppression. To make matters more complicated, one of Hayes’s electors from Oregon was disqualified, reducing his total to 165 and increasing the number of disputed votes to 20. Without these votes, Tilden would win the presidency.

Disputed Electoral Votes

With the electoral vote count still in dispute by November 11, 1876, Tilden seemed to have won with 184 votes, just one short of the majority needed. Hayes had 166 votes, but the 19 votes from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina were still in question. Both Republicans and Democrats claimed victory in these states, and fraud was alleged on both sides.

The dispute centered on which body of Congress had the authority to resolve the conflicting electors’ slates. By January 1877, with no resolution in sight, Congress and President Grant agreed to establish a bipartisan Electoral Commission. This commission, consisting of five representatives, five senators, and five Supreme Court justices, was intended to resolve the issue. To balance partisan interests, the commission included seven Democrats and seven Republicans, with Justice David Davis, an independent, as the 15th member. However, Davis was soon elected to the Senate, creating a vacancy. Justice Joseph P. Bradley, the most independent-minded remaining justice, replaced Davis on the Commission.

The Electoral Commission convened in February and, after deliberation, the eight Republicans on the Commission voted to award all 20 disputed electoral votes to Hayes. This decision sparked outrage among Democrats, who attempted a filibuster to prevent Congress from accepting the Commission’s findings. The filibuster eventually ended, and on March 2, 1877, Senator Thomas W. Ferry announced that Hayes and Wheeler had won the presidency and vice-presidency by an electoral margin of 185–184.

The Compromise of 1877

As Hayes’s inauguration approached, Republican and Democratic Congressional leaders negotiated a compromise at Wormley’s Hotel in Washington. Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South and accept the election of Democratic governments in the remaining contested Southern states. In return, Democrats accepted the results of the Electoral Commission’s decision. This agreement marked the end of Reconstruction and left freedmen vulnerable to the policies of Democratic state governments.

On April 3, 1877, Hayes ordered the withdrawal of federal troops from the South Carolina State House, and by April 20, he directed the removal of federal troops from New Orleans. This marked a significant shift in U.S. politics and effectively concluded the era of Reconstruction, leaving many of the rights of freedmen unprotected in the face of rising white Democratic control.

Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes (1877–1881)

Inauguration

Rutherford B. Hayes’s inauguration marked a unique departure from tradition due to its timing. On March 4, 1877, the official inauguration day, falling on a Sunday, Hayes took the presidential oath privately in the White House’s Red Room. This was a first in U.S. history. The public swearing-in ceremony took place the following day, March 5, on the East Portico of the Capitol. In his inaugural address, Hayes sought to calm the turbulent political climate, advocating for “wise, honest, and peaceful local self-government” and pledging reforms in civil service and a return to the gold standard. Despite these assurances, many Democrats remained skeptical of Hayes’s legitimacy, derisively referring to him as “Rutherfraud” or “His Fraudulency” throughout his term.

The South and the End of Reconstruction

A central issue of Hayes’s presidency was the end of Reconstruction. Although Hayes had been a supporter of Reconstruction policies, the political realities of his presidency forced a shift. The 45th Congress, dominated by Democrats, was unwilling to fund military garrisons in the South, a key component of Reconstruction efforts. By April 1877, Hayes began withdrawing federal troops from Southern states, with significant reductions in South Carolina and Louisiana. This retreat effectively ended federal oversight in the South and allowed Democrats to regain control.

Despite Hayes’s attempts to protect the rights of African Americans and strengthen Republican influence in the South, his efforts largely fell short. The reduction of federal oversight allowed the resurgence of Southern Democrats and the subsequent erosion of black civil rights. Hayes’s attempts to enforce voting rights laws through federal power faced obstacles, including efforts by Congress to limit federal oversight and funding for enforcement.

Civil Service Reform

One of Hayes’s primary goals was to reform the civil service system, which had long been based on the spoils system. Instead of awarding government jobs based on political patronage, Hayes aimed to implement a merit-based system. This stance put him at odds with influential figures in his party, particularly the Stalwarts, who supported the spoils system. Key opponents included Senator Roscoe Conkling, who led resistance against Hayes’s reform efforts.

Hayes’s commitment to civil service reform was demonstrated through appointments of reform advocates like Carl Schurz to key positions. However, he faced significant challenges, including resistance from established political figures and difficulties in passing reform legislation. Despite these obstacles, Hayes issued an executive order prohibiting political contributions from federal officeholders and took action against key figures in the New York Custom House, although his attempts to secure reform appointments faced setbacks in the Senate.

Throughout his presidency, Hayes advocated for continued reform, laying the groundwork for future legislation. While permanent civil service reform was not achieved during his term, his efforts provided a precedent for the Pendleton Act of 1883, which established a merit-based system for federal employment.

Dealing with Corruption

Hayes also addressed corruption in the postal service, particularly focusing on the “star route” scandal. Although he stopped new star route contracts, he allowed existing ones to continue. His administration faced criticism for alleged delays in investigating the corruption, but investigations ultimately found no compelling evidence against Hayes himself. The legal battles surrounding the star route contracts continued beyond his presidency, with mixed outcomes.

Conclusion

Rutherford B. Hayes’s presidency was marked by significant challenges and complex political dynamics. His efforts to end Reconstruction, reform the civil service, and address corruption were met with varying degrees of success and resistance. Despite the contentious environment, Hayes’s presidency laid important groundwork for future reforms and set precedents that influenced subsequent administrations.

Great Railroad Strike of 1877

In 1877, during Hayes’s first year as President, the United States faced its largest labor uprising to date—the Great Railroad Strike. The major railroads had cut employees’ wages multiple times in response to financial losses from the Panic of 1873. This led to workers at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad striking in Martinsburg, West Virginia, in July. The strike quickly spread to other railroads, including the New York Central, Erie, and Pennsylvania railroads, with thousands of workers participating.

The strike escalated into riots in Baltimore and Pittsburgh. Hayes initially hesitated to send federal troops but eventually did so to protect federal property and suppress the violence. Under Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, federal troops were deployed for the first time to break a strike against a private company. The unrest also spread to Chicago and St. Louis. By the end of July, the riots had subsided, and the troops returned to their barracks. While the railroads managed to return to operation, public sentiment turned against them, leading to improved working conditions and a halt to further wage cuts. Hayes himself acknowledged the need for a more equitable solution to labor disputes.

Currency Debate

Hayes confronted two significant currency issues. The Coinage Act of 1873 had stopped the minting of silver coins, tying the dollar to gold and worsening the Panic of 1873’s effects. Farmers and laborers advocated for the return of silver coinage to increase the money supply. In response, Congress passed the Bland–Allison Act of 1878, which mandated the coinage of silver. Hayes vetoed the bill, fearing it would lead to inflation, but Congress overrode his veto.

The second issue was the redemption of greenbacks (fiat currency) for gold, mandated by the Specie Payment Resumption Act of 1875. Hayes and Treasury Secretary John Sherman prepared for this transition, but the public’s confidence in redeeming greenbacks was limited. By 1879, only a small fraction of greenbacks were redeemed. The compromise of the Bland–Allison Act and specie resumption helped stabilize the currency, and the debates over silver and greenbacks diminished during Hayes’s presidency.

Foreign Policy

Hayes’s foreign policy focused primarily on Latin America and China. In 1878, he arbitrated a territorial dispute between Argentina and Paraguay, awarding land to Paraguay. Hayes was concerned about European control over a potential canal across the Isthmus of Panama, advocating for American control under the Monroe Doctrine.

The Mexican border issue involved lawless bands crossing into Texas. Hayes granted the Army permission to pursue these bands into Mexican territory, leading to tensions with Mexican President Porfirio Díaz. Eventually, an agreement was reached to jointly address border violence, and the pursuit order was revoked in 1880.

Hayes also dealt with the Chinese immigration issue. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1879 aimed to limit Chinese immigration, which Hayes vetoed, arguing against abrogating treaties without negotiation. The veto led to political backlash, but a revised Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882 after Hayes left office.

Indian Policy

Hayes, along with Interior Secretary Carl Schurz, implemented a policy aimed at assimilating American Indians into white culture. This included educational training and dividing Indian lands into individual allotments under the Dawes Act of 1887. Despite intentions of self-sufficiency and peace, this policy led to significant loss of Indian land and problems with speculators.

Conflicts with various tribes included the Nez Perce War, the Bannock War, and the White River War. Hayes intervened in the Ponca tribe’s removal issue, allowing them to return to Nebraska or stay in Indian Territory. Hayes’s policies were aimed at reducing fraud and improving conditions for American Indians, though the outcomes were mixed.

Great Western Tour of 1880

In 1880, Hayes undertook a 71-day tour of the Western United States, becoming the second sitting president to travel west of the Rockies. His trip, organized with the help of William T. Sherman, included visits to Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, California, Oregon, Washington, and several southwestern states. The tour aimed to bolster national unity and showcase presidential engagement with the growing Western territories.

White House and Personal Policies

Hayes and his wife Lucy implemented a policy of keeping the White House alcohol-free, which led to Lucy being nicknamed “Lemonade Lucy.” Although some critics viewed this as parsimony, Hayes used the savings to enhance other aspects of White House entertaining and strengthened support among prohibitionists.

Judicial Appointments

Hayes appointed two Associate Justices to the Supreme Court: John Marshall Harlan and William Burnham Woods. Harlan was confirmed despite some Senate dissent and served for 34 years. Woods, initially a disappointment to Hayes, was appointed to fill a second vacancy. Hayes also attempted to fill a third vacancy with Stanley Matthews, but the nomination faced significant opposition and was not confirmed until Garfield’s presidency. Matthews’s tenure included an important ruling in Yick Wo v. Hopkins, which advanced civil rights protections.

Overall, Hayes’s presidency was marked by significant challenges and reforms in labor relations, currency policy, foreign relations, and Indian affairs, leaving a complex legacy.

Post-Presidency (1881–1893)

After completing his term as President, Rutherford B. Hayes honored his commitment to not seek re-election. During the 1880 Republican National Convention, he actively opposed the nominations of Roscoe Conkling and Chester A. Arthur for Vice President, as well as Ulysses S. Grant’s bid for a third presidential term. Hayes, having previously criticized Grant’s presidency, felt strongly that a president should serve a single six-year term. He found satisfaction in the election of fellow Ohio Republican James A. Garfield as his successor and worked with him on appointments for the new administration.

Upon leaving the White House, Hayes and his family returned to their estate at Spiegel Grove. In 1881, Hayes was elected as a companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States and served as its national president from 1888 until his death. Although he remained a staunch Republican, Hayes was not dismayed by Democrat Grover Cleveland’s election in 1884, appreciating Cleveland’s stance on civil service reform. He was also pleased with the political ascent of William McKinley, his former army comrade and political protégé.

Hayes devoted much of his post-presidency life to advocating for educational charities and federal education subsidies for children. He believed education was crucial for addressing societal divisions and empowering individuals. Hayes, who had helped found Ohio State University as governor, was appointed to its Board of Trustees in 1887. He championed both vocational and academic education, arguing for the importance of skilled labor. Although he lobbied Congress unsuccessfully for federal aid for education, he supported initiatives such as the Slater Fund scholarships for black students, including W. E. B. Du Bois in 1892. Hayes also advocated for improved prison conditions.

In retirement, Hayes was deeply concerned about economic inequality. He expressed his worries about the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few and its adverse effects on democracy and social justice. He wrote about the dangers of extreme wealth and its impact on poverty, ignorance, and societal vice. Hayes believed that understanding these issues was crucial for finding remedies and supported reforms in laws regulating corporations, inheritance, and taxation.

The death of his wife, Lucy, in 1889 was a profound loss for Hayes. He felt her absence deeply, describing it as if the soul had departed from Spiegel Grove. Following Lucy’s death, his daughter Fanny became his companion on travels, and he enjoyed visits from his grandchildren. In 1890, Hayes chaired the Lake Mohonk Conference on the Negro Question, discussing racial issues with reformers. He passed away from a heart attack on January 17, 1893, at the age of 70. His final words reflected his longing to be reunited with his wife.

Hayes was interred in Oakwood Cemetery in Fremont, Ohio. In 1915, his remains were moved to Spiegel Grove to rest alongside Lucy. The Hayes Commemorative Library and Museum, the first presidential library in the U.S., opened on the site in 1916, thanks to contributions from Ohio and the Hayes family.

In honor of Hayes, the U.S. Post Office issued a stamp bearing his likeness in 1922 on the centennial of his birth, and another stamp in 1938. The U.S. Mint also released a “Golden Dollar” featuring Hayes in 2011. Additionally, Hayes’s arbitration of the 1878 dispute between Argentina and Paraguay, which favored Paraguay, led to the naming of the Presidente Hayes Department in Paraguay and other local honors, including a soccer team and a postage stamp. Hayes County, Nebraska, was also named in his honor.

Hayes was elected to the American Antiquarian Society in 1890. His legacy includes Rutherford B. Hayes High School in Delaware, Ohio, and Hayes Hall at Ohio State University, the latter of which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The City of Delaware also commemorated Hayes with a statue.