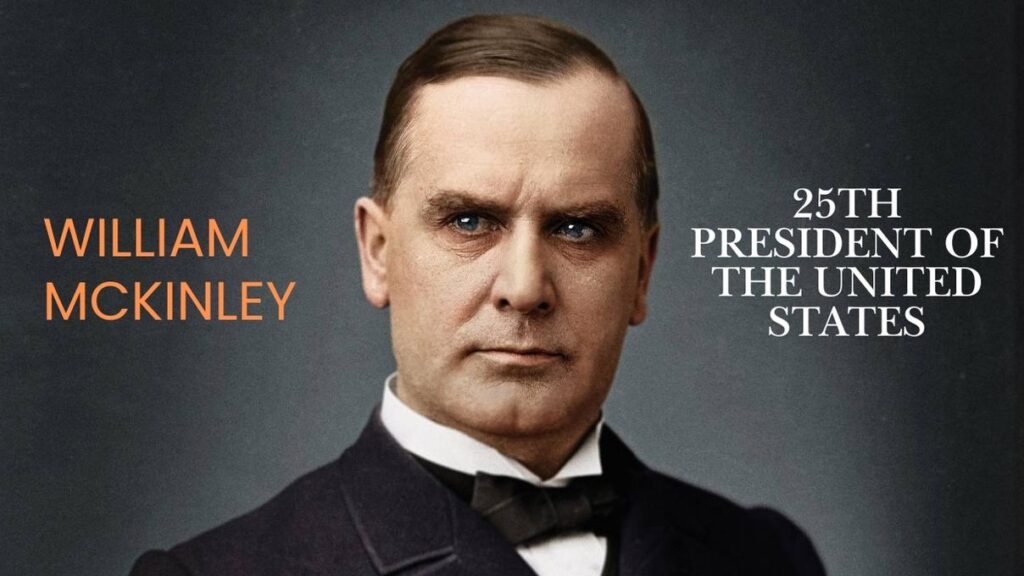

James Madison

James Madison (March 16, 1751 – June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed the “Father of the Constitution” for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights.

Madison was born into a prominent slave-owning planter family in Virginia. He served as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and the Continental Congress during and after the American Revolutionary War. Dissatisfied with the weak national government established by the Articles of Confederation, he helped organize the Constitutional Convention, which produced a new constitution designed to strengthen republican government against democratic assembly.

Madison’s Virginia Plan was the basis for the convention’s deliberations, and he was an influential voice at the convention. He became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify the Constitution and joined Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in writing The Federalist Papers, a series of pro-ratification essays that remains prominent among works of political science in American history. Madison emerged as an important leader in the House of Representatives and was a close adviser to President George Washington.

During the early 1790s, Madison opposed the economic program and the accompanying centralization of power favored by Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton. Alongside Thomas Jefferson, he organized the Democratic–Republican Party in opposition to Hamilton’s Federalist Party. After Jefferson was elected president in 1800, Madison served as his Secretary of State from 1801 to 1809 and supported Jefferson in the case of Marbury v. Madison. While Madison was Secretary of State, Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase, and later, as President, Madison oversaw related disputes in the Northwest Territories.

Madison was elected president in 1808. Motivated by desire to acquire land held by Britain, Spain, and Native Americans, and after diplomatic protests with a trade embargo failed to end British seizures of American shipped goods, Madison led the United States into the War of 1812. Although the war ended inconclusively, many Americans viewed the war’s outcome as a successful “second war of independence” against Britain.

Madison was re-elected in 1812, albeit by a smaller margin. The war convinced Madison of the necessity of a stronger federal government. He presided over the creation of the Second Bank of the United States and the enactment of the protective Tariff of 1816. By treaty or through war, Native American tribes ceded 26,000,000 acres (11,000,000 ha) of land to the United States under Madison’s presidency.

After leaving office in 1817, Madison retreated to his Virginia plantation, Montpelier, where he lived until his death in 1836. It’s important to acknowledge that Madison was a slave owner throughout his life. In one documented instance, he freed a slave in 1783 to quell potential rebellion at Montpelier. However, he did not emancipate any slaves through his will.

Despite his complexities, historians consider James Madison a pivotal Founding Father. He is generally ranked as an above-average president, although his support for slavery and handling of the War of 1812 draw criticism. Madison’s legacy is reflected in numerous landmarks across the country, including public and private institutions like Madison Square Garden, James Madison University, the James Madison Memorial Building, and the USS James Madison.

Early Life and Education of James Madison

Early Life

- Birth: James Madison was born on March 16, 1751, at Belle Grove Plantation near Port Conway, Virginia. He was the eldest of twelve children.

- Family Background: Madison came from a prominent Virginia planter family. His father, James Madison Sr., was a successful planter and owned a large plantation in Orange County, Virginia. His mother, Nelly Conway Madison, belonged to a wealthy Virginia family.

Childhood and Upbringing

- Health: Madison was often in poor health as a child, suffering from psychosomatic, or stress-induced, seizures and other ailments. This frailty shaped his studious and contemplative nature.

- Early Education: Madison was initially educated at home by his mother and tutors. His early education included reading, writing, arithmetic, and the classics.

Formal Education

- Schooling: Around age 11, Madison was sent to a boarding school run by Donald Robertson in King and Queen County, Virginia. Robertson’s rigorous curriculum included the study of Latin, Greek, French, mathematics, and geography. Madison later referred to Robertson as one of the most influential teachers he had.

- Preparation for College: In 1767, Madison returned to his family’s estate, Montpelier, where he continued his studies under the Reverend Thomas Martin, who prepared him for college.

College Education

- Princeton University: In 1769, Madison enrolled at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). He chose Princeton over the College of William & Mary to avoid the humid climate of Williamsburg, which he believed would be detrimental to his health.

- Academic Rigor: Madison completed Princeton’s three-year course in just two years, graduating in 1771. He excelled in classical languages, philosophy, and Enlightenment ideas, studying under the college’s president, John Witherspoon, a prominent Scottish American philosopher and a leader of the Presbyterian Church.

- Intellectual Influences: At Princeton, Madison was deeply influenced by Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke, Isaac Newton, and David Hume. He also engaged in rigorous debates about political theory and governance, laying the foundation for his future political philosophy.

Post-College Years

- Further Studies: After graduating, Madison stayed at Princeton for an additional year to study Hebrew and political philosophy. He returned to Montpelier in 1772, continuing his self-education by reading law, history, and political theory extensively.

- Role in Community: Upon returning home, Madison became involved in local politics and governance, gradually stepping onto the national stage as the American colonies moved towards independence.

Madison’s early education and intellectual development were characterized by a combination of rigorous classical training and exposure to Enlightenment ideas, which profoundly influenced his later contributions to the formation of the United States.

James Madison’s Role in the American Revolution and the Articles of Confederation

American Revolution

Early Involvement in Politics:

- Virginia Convention (1776): Madison’s political career began in earnest when he was elected to the Virginia Convention in 1776. This body was responsible for drafting Virginia’s first constitution, a key step towards independence from British rule.

- Committee of Public Safety: Madison served on the committee responsible for ensuring the colony’s defense and managing its military affairs, demonstrating his early commitment to the Revolutionary cause.

Virginia Declaration of Rights:

- Collaboration with George Mason: Madison worked closely with George Mason on the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Although Mason was the primary author, Madison contributed significantly, particularly by advocating for a broader guarantee of religious freedom.

Service in the Continental Congress:

- Delegate (1780-1783): Madison was elected to the Continental Congress in 1780. His work during this period was crucial in supporting the war effort and managing the fledgling nation’s diplomatic and financial challenges.

- Advocacy for Stronger Federal Government: Madison became increasingly convinced of the need for a stronger federal government, a stance that would later shape his contributions to the U.S. Constitution.

Articles of Confederation

Initial Adoption:

- Ratification (1781): The Articles of Confederation, which served as the United States’ first constitution, were ratified in 1781. They established a loose confederation of sovereign states with a weak central government.

Madison’s Criticisms:

- Weak Central Government: Madison quickly recognized the weaknesses in the Articles. The central government lacked the authority to tax, regulate commerce, or enforce laws directly upon the states, leading to financial and logistical difficulties.

- Inefficiency and Ineffectiveness: Madison was particularly concerned about the inefficiency of the government under the Articles, noting the difficulty in passing legislation and the lack of executive leadership.

Efforts to Reform:

- Virginia Plan: Madison played a pivotal role in proposing the Virginia Plan, which called for a complete overhaul of the Articles. This plan advocated for a stronger national government with a system of checks and balances.

- Annapolis Convention (1786): Frustrated by the Articles’ shortcomings, Madison helped organize the Annapolis Convention to discuss revising them. Although the convention had limited attendance, it led to the calling of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

Transition to the U.S. Constitution:

- Constitutional Convention (1787): Madison’s advocacy for reform culminated in the Constitutional Convention, where he emerged as a leading voice. His ideas significantly shaped the new Constitution, particularly through his contributions to the drafting process and his detailed notes on the proceedings.

- The Federalist Papers: To support the ratification of the new Constitution, Madison, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, wrote The Federalist Papers. Madison’s essays, including Federalist No. 10 and No. 51, remain foundational texts in American political theory.

Madison’s experiences during the American Revolution and his critical assessment of the Articles of Confederation were instrumental in his development as a statesman and architect of the U.S. Constitution. His insistence on a stronger, more effective federal government laid the groundwork for the nation’s current system of governance.

James Madison and the Ratification of the Constitution

Role in the Constitutional Convention

Constitutional Convention (1787):

- Key Delegate: Madison played a crucial role at the Constitutional Convention held in Philadelphia in 1787. Known as the “Father of the Constitution,” he arrived well-prepared, having studied various forms of government extensively.

- Virginia Plan: Madison introduced the Virginia Plan, which proposed a strong national government with three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. This plan served as the basis for discussions and greatly influenced the final structure of the Constitution.

Advocacy for Ratification

The Federalist Papers:

- Co-Authorship: To support the ratification of the new Constitution, Madison, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, wrote a series of essays known as The Federalist Papers. These 85 essays were published under the pseudonym “Publius” in various New York newspapers.

- Key Essays: Madison’s contributions include some of the most influential essays:

- Federalist No. 10: Addresses the dangers of factionalism and argues for a large republic where diverse interests can check each other.

- Federalist No. 51: Explains the system of checks and balances and the importance of separating powers within the government.

Arguments for a Strong Central Government:

- National Defense and Stability: Madison argued that a strong central government was necessary to provide for national defense, maintain order, and ensure the country’s stability.

- Economic Regulation: He emphasized the importance of a centralized authority to regulate interstate commerce and manage economic policy effectively.

Ratification Process

State Ratifying Conventions:

- State-by-State Ratification: The Constitution required ratification by nine of the thirteen states to become effective. Each state held its own convention to debate and vote on the Constitution.

- Virginia Convention (1788): Madison was a leading advocate for ratification in his home state of Virginia, facing strong opposition from prominent figures like Patrick Henry and George Mason who feared that the new government would have too much power.

Bill of Rights:

- Addressing Concerns: To address concerns about the lack of explicit protections for individual liberties, Madison promised to support amendments that would safeguard these rights.

- Drafting the Amendments: True to his word, Madison introduced a series of amendments to the First Congress in 1789, which became the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791.

Success of Ratification:

- Final Ratification: The Constitution was successfully ratified by the required nine states by June 21, 1788, with New Hampshire being the ninth. Virginia and New York, two crucial states, ratified shortly thereafter, largely due to the efforts of advocates like Madison.

- Implementation: The new government under the Constitution commenced operations on March 4, 1789, with George Washington inaugurated as the first President of the United States and Madison serving as a key member of the first Congress.

Legacy

Enduring Influence:

- Framework for Government: Madison’s contributions to the ratification process and his role in drafting the Constitution and the Bill of Rights have left a lasting legacy, establishing the framework for the U.S. government that endures today.

- Champion of Federalism: Madison’s advocacy for a strong yet balanced federal government helped shape the foundational principles of American democracy, balancing the needs for effective governance and protection of individual liberties.

James Madison: Congressman and Party Leader (1789–1801)

Congressman in the First Federal Congress

Tenure:

- Elected to the House: Madison was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1789, serving Virginia’s 5th congressional district. He served in the House from 1789 to 1797.

Key Contributions:

- Bill of Rights: One of Madison’s most significant achievements as a congressman was drafting and championing the Bill of Rights. He introduced these amendments to address the concerns of Anti-Federalists who feared that the new Constitution did not sufficiently protect individual liberties.

- First Ten Amendments: These amendments, ratified in 1791, guarantee fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, religion, and assembly, and protections against unreasonable searches and seizures.

- Revenue Legislation: Madison played a crucial role in shaping the nation’s financial system. He was instrumental in passing the Tariff Act of 1789, which imposed duties on imports to raise revenue for the federal government and protect American industries.

Political Philosophy and Leadership:

- Advocate for Limited Government: Madison believed in a federal government with limited powers, a stance that would later define his political alignment with the Democratic-Republican Party.

- Debates on Executive Power: He participated in debates over the scope of executive power, advocating for a balance that would prevent any single branch from becoming too powerful.

Formation of the Democratic-Republican Party

Partisan Split:

- Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans: The early 1790s saw the emergence of the first political parties in the United States. The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, supported a strong central government and a loose interpretation of the Constitution. Madison, along with Thomas Jefferson, formed the Democratic-Republican Party, advocating for states’ rights and a strict interpretation of the Constitution.

Opposition to Hamilton’s Policies:

- National Bank: Madison opposed Hamilton’s proposal for a national bank, arguing that it was unconstitutional and concentrated too much power in the hands of the federal government.

- Economic Vision: Madison and Jefferson favored an agrarian economy and were wary of the financial and commercial policies that Hamilton promoted, which they believed favored wealthy elites and Northern interests.

The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions:

- Response to Alien and Sedition Acts: In 1798, in response to the Federalist-backed Alien and Sedition Acts, Madison and Jefferson drafted the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. These resolutions argued that states had the right to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional, asserting the principle of states’ rights.

Leadership and Legacy

Leadership in Congress:

- Guiding Legislation: Madison’s leadership in Congress helped guide key legislative initiatives and shape the new nation’s governance structures. He was respected for his deep knowledge of constitutional issues and his ability to build consensus.

Founding of the Democratic-Republican Party:

- Party Ideals: The Democratic-Republican Party, co-founded by Madison, emphasized limited government, protection of individual liberties, and support for agrarian interests. This party would dominate American politics in the early 19th century.

- Influence on Jefferson: Madison’s ideas and political strategies greatly influenced Thomas Jefferson, who became the third President of the United States in 1801. Madison served as Jefferson’s close advisor and later succeeded him as the fourth President.

End of Congressional Career:

- Return to Virginia: After leaving Congress in 1797, Madison returned to Virginia but remained active in national politics. His experience as a legislator and party leader provided a strong foundation for his future roles as Secretary of State and President.

Madison’s tenure as a congressman and party leader was marked by his unwavering commitment to the principles of republicanism and limited government. His efforts during this period helped shape the foundational policies and political landscape of the early United States.

Founding the Democratic-Republican Party

Background and Context

Emergence of Political Factions:

- Early Partisan Divides: In the early years of the United States under the new Constitution, political factions began to emerge around differing visions for the country’s future. The major divide was between those who supported a strong central government and those who advocated for states’ rights and limited federal power.

- Federalist Policies: Led by Alexander Hamilton, the Federalists supported a robust central government, a strong financial system with a national bank, and policies that encouraged industrial and commercial growth. These policies were viewed by some as favoring the wealthy and urban interests, particularly in the Northern states.

Madison and Jefferson’s Opposition:

- Philosophical Differences: James Madison and Thomas Jefferson emerged as leaders of the opposition to the Federalist agenda. They feared that Hamilton’s policies would create a centralized and potentially tyrannical government, undermining the republic’s democratic principles.

- Vision for America: Madison and Jefferson envisioned an agrarian-based republic where states retained significant power and individual liberties were protected against federal encroachment. They believed in strict adherence to the Constitution to limit federal authority.

Formation of the Democratic-Republican Party

Alliance with Jefferson:

- Shared Ideals: Madison and Jefferson, both champions of individual liberties and states’ rights, formed a political alliance. Their collaboration was rooted in their shared opposition to Federalist policies and their belief in a limited, decentralized federal government.

- Party Formation: This alliance led to the creation of the Democratic-Republican Party, also known simply as the Republican Party at the time. It formally organized in the early 1790s, becoming the primary opposition to the Federalist Party.

Key Principles and Policies:

- Strict Constitutional Interpretation: The Democratic-Republicans advocated for a strict interpretation of the Constitution, arguing that the federal government should exercise only those powers explicitly granted by the document.

- States’ Rights: They emphasized the importance of states’ rights and sovereignty, opposing federal measures that they believed infringed upon the autonomy of the states.

- Agrarian Focus: The party promoted an agrarian-based economy, viewing independent farmers as the backbone of the republic. They were skeptical of banking and industrial interests, which they believed could corrupt the government and concentrate power among the elite.

Opposition to Federalist Policies:

- National Bank: Madison and Jefferson vehemently opposed Hamilton’s plan to establish a national bank, arguing that it was unconstitutional and would create a dangerous financial monopoly.

- Alien and Sedition Acts: In response to the Federalist-backed Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, which they saw as repressive and unconstitutional, Madison and Jefferson drafted the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. These documents asserted that states had the right to nullify federal laws deemed unconstitutional.

Political Strategy and Influence

Grassroots Mobilization:

- Political Clubs: The Democratic-Republicans organized political clubs and societies to mobilize grassroots support. These organizations played a critical role in spreading their message and galvanizing public opinion against Federalist policies.

- Media and Publications: They also used newspapers and pamphlets to communicate their ideas and criticisms of the Federalist administration. This helped build a broad base of support among the electorate.

Electoral Success:

- Elections of 1796 and 1800: The Democratic-Republicans gained significant ground in the elections of 1796, though John Adams, a Federalist, won the presidency. However, in the election of 1800, Thomas Jefferson defeated Adams, marking a significant victory for the Democratic-Republican Party.

- “Revolution of 1800”: Jefferson’s election, often referred to as the “Revolution of 1800,” marked the first peaceful transfer of power between political parties in the United States and solidified the Democratic-Republicans’ dominance.

Legacy

Long-term Impact:

- Enduring Influence: The Democratic-Republican Party dominated American politics for the next two decades. Madison himself would become the fourth President of the United States, continuing the policies and philosophies of the party.

- Evolution of Political Parties: The Democratic-Republican Party’s emphasis on states’ rights and limited federal government laid the groundwork for future political movements and debates in American history. Over time, the party evolved and eventually split, with its legacy influencing both the modern Democratic and Republican parties.

Madison’s role in founding the Democratic-Republican Party was pivotal in shaping the early political landscape of the United States. His vision of a limited federal government and strong protections for individual liberties and states’ rights significantly influenced the nation’s development during its formative years.

James Madison: Marriage and Family

Marriage to Dolley Payne Todd

Meeting Dolley:

- Introduction: James Madison met Dolley Payne Todd in 1794. At the time, Dolley was a widow, having lost her first husband, John Todd, and one of her sons to a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia.

- Mutual Acquaintance: They were introduced by Aaron Burr, a mutual acquaintance, and Madison quickly became enamored with Dolley, who was known for her charm, beauty, and social grace.

Marriage:

- Wedding Date: James Madison and Dolley Payne Todd were married on September 15, 1794.

- Age Difference: At the time of their marriage, Madison was 43 years old, and Dolley was 26.

Dolley Madison’s Role

First Lady:

- Social Leader: As the wife of the Secretary of State and later the President, Dolley Madison became a prominent social figure in Washington, D.C. Her charm and hospitality helped establish the social customs of the capital.

- White House Hostess: When Madison became President in 1809, Dolley played a key role in hosting events at the White House, making it a center of social and political life. She is often credited with creating the role of the First Lady as we understand it today.

Impact on Madison’s Career:

- Supportive Partner: Dolley’s social skills and political acumen complemented Madison’s more reserved nature. She provided crucial support, helping him navigate the complexities of Washington society and politics.

- War of 1812: During the War of 1812, Dolley became a national heroine for saving valuable state papers and a famous portrait of George Washington when the British burned the White House in 1814.

Family Life

Children:

- No Biological Children: James and Dolley Madison did not have any children together. However, Dolley had two sons from her first marriage, John Payne Todd and William Temple Todd. William died in infancy.

- John Payne Todd: Madison helped raise Dolley’s surviving son, John Payne Todd, who unfortunately led a troubled life marked by financial irresponsibility and issues with alcoholism. Despite Madison’s efforts to support and guide him, Payne Todd’s behavior was a continual source of stress for the family.

Montpelier:

- Home Life: After Madison’s presidency, he and Dolley retired to their estate, Montpelier, in Virginia. There, they enjoyed a quieter life, though Madison remained engaged in political discourse and correspondence.

- Dolley’s Management: Dolley played an active role in managing the household and entertaining guests. Montpelier became a hub of intellectual and political conversation, reflecting the couple’s enduring influence on American political life.

Later Years:

- Financial Difficulties: In their later years, Madison and Dolley faced financial difficulties, partly due to John Payne Todd’s debts. Despite these challenges, Dolley continued to be a supportive and devoted partner to Madison.

- Madison’s Death: James Madison died on June 28, 1836, at Montpelier. After his death, Dolley returned to Washington, D.C., where she lived until her own death in 1849. She continued to be a respected and beloved figure in American society.

James and Dolley Madison’s marriage was marked by mutual respect, partnership, and a shared commitment to public service. Dolley’s dynamic presence complemented Madison’s reserved demeanor, and their partnership played a significant role in shaping both their personal lives and Madison’s political career. Their enduring legacy includes not only their contributions to the early United States but also the model of a supportive and influential political partnership.

James Madison During the Adams Presidency

Background of the Adams Presidency

John Adams’ Election:

- Election of 1796: John Adams, a Federalist, won the presidential election of 1796, defeating Thomas Jefferson, who became Vice President under the rules of the time, as the candidate with the second highest number of electoral votes. This created a unique situation where the President and Vice President were from opposing political parties.

Madison’s Political Stance

Opposition Leader:

- Federalist Policies: As a leading figure in the Democratic-Republican Party, James Madison strongly opposed the Federalist policies of the Adams administration. He was particularly critical of Adams’ approach to foreign policy and civil liberties.

- Partisan Tensions: The political environment was highly charged, with significant partisan tensions between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. Madison, along with Thomas Jefferson, worked to consolidate opposition to the Federalist agenda.

Key Issues and Events

XYZ Affair:

- Diplomatic Conflict: The XYZ Affair was a diplomatic incident between the United States and France, occurring in 1797-1798, where French agents demanded bribes and loans to initiate negotiations to avoid war. When news of this broke, it led to public outrage in the U.S. and a quasi-war with France.

- Madison’s View: Madison was critical of how the Adams administration handled the affair, arguing that it had exacerbated tensions with France unnecessarily. He saw it as part of the Federalists’ broader strategy to increase federal power under the guise of national security.

Alien and Sedition Acts:

- Legislation: In 1798, the Federalist-controlled Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which included powers to deport foreigners and make it harder for new immigrants to vote. The Sedition Act also criminalized making false statements against the federal government.

- Madison’s Opposition: Madison viewed these acts as severe overreaches of federal power and direct violations of constitutional rights, particularly the First Amendment. He, along with Jefferson, saw these acts as tools for the Federalists to suppress opposition.

Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions:

- Drafting Resolutions: In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts, Madison and Jefferson drafted the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions in 1798-1799. These resolutions argued that states had the right to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional.

- Principle of States’ Rights: The resolutions were a significant assertion of the states’ rights doctrine, emphasizing that the federal government was a compact of states and that states could judge the constitutionality of federal actions.

Political Strategy and Activities

Building Opposition:

- Party Organization: Madison and Jefferson worked tirelessly to build a strong opposition party. They focused on grassroots organization, using political clubs, newspapers, and correspondence to spread their message and galvanize support.

- Election of 1800: Their efforts laid the groundwork for the “Revolution of 1800,” where Jefferson won the presidency, marking a peaceful transfer of power and a significant victory for the Democratic-Republicans.

Legacy and Impact

Defending Liberties:

- Protector of Rights: Madison’s opposition to the Adams administration’s policies, particularly the Alien and Sedition Acts, highlighted his commitment to protecting civil liberties and limiting federal power.

- Champion of States’ Rights: His work on the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions underscored his belief in the importance of states as a check against potential federal overreach.

Long-term Influence:

- Political Realignment: Madison’s leadership during the Adams presidency helped shape the emerging two-party system in the United States, clearly delineating the ideological lines between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans.

- Preparation for Leadership: This period of intense political activity and opposition prepared Madison for his future roles as Secretary of State under Jefferson and eventually as President, where he continued to advocate for many of the principles he defended during the Adams presidency.

Madison’s actions during the Adams presidency were crucial in shaping the political landscape of the early United States. His steadfast opposition to what he saw as unconstitutional overreach by the federal government and his efforts to build a strong opposition party were key to the eventual triumph of the Democratic-Republicans and the principles they stood for.

James Madison as Secretary of State (1801–1809)

Appointment and Early Actions

Appointment:

- Thomas Jefferson’s Administration: James Madison was appointed Secretary of State by President Thomas Jefferson and served from March 5, 1801, to March 3, 1809. Madison was a close ally and confidant of Jefferson, and his appointment was seen as a natural choice given their shared political views and long-standing partnership.

Focus on Peaceful Foreign Policy:

- Jeffersonian Principles: Madison’s tenure as Secretary of State was marked by efforts to adhere to Jeffersonian principles of limited government, non-interventionism, and peaceful foreign relations.

Key Issues and Events

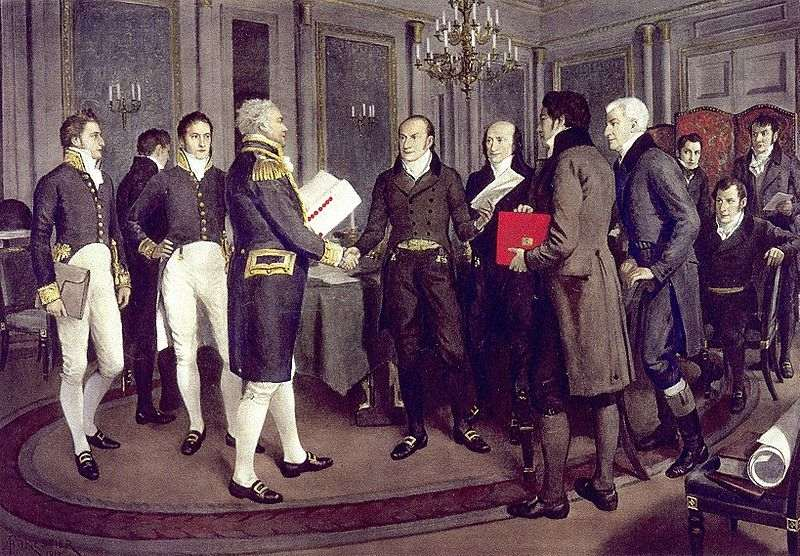

Louisiana Purchase (1803):

- Negotiations with France: One of the most significant achievements during Madison’s tenure was the Louisiana Purchase. Madison played a crucial role in negotiating the deal with France, which doubled the size of the United States.

- Constitutional Concerns: Despite some constitutional concerns about the federal government’s authority to acquire new territory, Madison and Jefferson decided to proceed, arguing that the opportunity was too valuable to pass up.

Challenges with Britain and France:

- Neutral Trade Rights: The early 1800s saw ongoing conflicts between Britain and France, which impacted American trade. Both nations-imposed restrictions that violated U.S. neutral trade rights.

- Impressment: The British practice of impressment, or forcibly recruiting American sailors into the Royal Navy, was a particularly contentious issue.

Embargo Act (1807):

- Economic Sanctions: In response to continued violations of American neutral rights, Madison and Jefferson implemented the Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited American ships from trading with foreign ports.

- Intended to Avoid War: The embargo was intended as a peaceful means to pressure Britain and France into respecting American neutrality without resorting to war.

- Economic Impact: The embargo had severe economic repercussions, particularly in the U.S. shipping and export industries, leading to significant domestic opposition.

Non-Intercourse Act (1809):

- Replacement of Embargo Act: As the Embargo Act proved economically damaging and politically unpopular, it was replaced by the Non-Intercourse Act, which specifically targeted Britain and France while allowing trade with other nations.

- Continued Struggles: Despite these measures, tensions with Britain and France remained unresolved, setting the stage for future conflicts.

Domestic Affairs

Internal Developments:

- Support for Jefferson’s Policies: Madison supported Jefferson’s domestic policies, including efforts to reduce the national debt, cut military expenditures, and limit the size and scope of the federal government.

- Promotion of Agrarian Interests: Consistent with their vision of an agrarian republic, Madison and Jefferson promoted policies that favored farmers and rural interests over industrial and commercial sectors.

Preparing for the Presidency

Building Political Alliances:

- Democratic-Republican Party: Madison’s tenure as Secretary of State helped solidify his position as a leading figure in the Democratic-Republican Party, preparing him for his eventual run for the presidency.

- Successor to Jefferson: Madison was seen as Jefferson’s natural successor, sharing the same political ideology and vision for the country.

Foreign Policy Experience:

- Diplomatic Challenges: Madison’s experience dealing with complex foreign policy issues, including the Louisiana Purchase, trade conflicts, and the embargo, provided him with valuable experience that would be crucial during his presidency.

Legacy and Impact

Foundational Foreign Policy:

- Shaping U.S. Diplomacy: Madison’s tenure as Secretary of State was instrumental in shaping early U.S. foreign policy, particularly in terms of expansion and efforts to assert American neutrality and sovereignty on the global stage.

- Precedent for Future Leaders: His actions set important precedents for future American diplomacy, including the use of economic sanctions as a tool of foreign policy.

Challenges and Criticisms:

- Economic Consequences: While the Embargo Act aimed to protect American interests without resorting to war, its economic fallout highlighted the challenges of balancing idealism with practical governance.

- Foundation for War of 1812: The unresolved issues with Britain and France during Madison’s tenure as Secretary of State contributed to the eventual outbreak of the War of 1812 during his presidency.

James Madison’s time as Secretary of State was marked by significant achievements and challenges. His efforts in expanding U.S. territory, navigating complex international conflicts, and laying the groundwork for American diplomacy were crucial in shaping the nation’s early foreign policy. These experiences not only solidified his role as a key figure in Jeffersonian politics but also prepared him for the responsibilities he would face as the fourth President of the United States.

1808 Presidential Election

Context and Background

End of Jefferson’s Presidency:

- Two-Term Tradition: By 1808, Thomas Jefferson had completed two terms as President and adhered to the informal tradition of not seeking a third term, setting a precedent for future presidents.

Democratic-Republican Dominance:

- Political Landscape: The Democratic-Republican Party was dominant in American politics, largely due to the unpopularity of Federalist policies and the successes of Jefferson’s administration.

James Madison as a Leading Candidate:

- Jefferson’s Support: James Madison, then serving as Secretary of State, was Jefferson’s preferred successor. Madison’s close association with Jefferson and his key role in shaping the administration’s policies made him a natural candidate.

Nomination Process

Democratic-Republican Party:

- Caucus Nomination: The Democratic-Republican congressional caucus, which served as the party’s nominating body, selected James Madison as their candidate for the presidency. Madison’s primary competition within the party included James Monroe and George Clinton.

- Running Mate: George Clinton, the sitting Vice President, was chosen as Madison’s running mate.

Federalist Party:

- Charles Cotesworth Pinckney: The Federalists nominated Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a veteran statesman and diplomat who had previously been the party’s candidate in the 1804 election. Pinckney’s military and diplomatic experience made him a respected figure, but he faced an uphill battle against the Democratic-Republican dominance.

- Running Mate: Rufus King was selected as Pinckney’s running mate.

Campaign and Issues:

- The campaign focused on a range of issues, including foreign policy, trade, and the economy. Tensions with Britain and France, which were at war with each other, posed significant challenges for American trade and diplomacy.

- The Embargo Act of 1807, implemented by Jefferson’s administration in response to trade restrictions imposed by Britain and France, had caused economic hardship for many Americans. Both parties offered different approaches to addressing these challenges, with Madison advocating for a continuation of Jeffersonian policies and Pinckney emphasizing his experience and credentials.

Results:

- James Madison won the election in a landslide, receiving 122 electoral votes compared to Pinckney’s 47. Madison carried most of the states, including key battlegrounds such as Pennsylvania, New York, and Virginia.

- Madison’s victory solidified the Democratic-Republican Party’s hold on power and marked the beginning of his presidency, during which he would face challenges including the War of 1812 and territorial expansion.

The 1808 election reaffirmed the strength of the Democratic-Republican Party and signaled a continuation of Jeffersonian policies under Madison’s leadership.

James Madison’s Presidency (1809–1817)

Inauguration of James Madison and Composition of His Cabinet

Inauguration of James Madison

Date and Location:

- James Madison was inaugurated as the fourth President of the United States on March 4, 1809.

- The inauguration took place in Washington, D.C., at the U.S. Capitol Building.

Ceremony Details:

- Madison’s inauguration followed the established customs and protocols of the time, including an inaugural address delivered to Congress.

- The event was likely a solemn occasion, reflecting the challenges facing the nation at the time, including tensions with Britain and France and economic difficulties.

Composition of Madison’s Cabinet

Secretary of State:

- Robert Smith (1809–1811): Initially appointed as Secretary of the Navy by Thomas Jefferson, Robert Smith was later transferred to the position of Secretary of State by Madison. However, Smith’s tenure was marked by internal disputes and disagreements with Madison, leading to his resignation in 1811.

- James Monroe (1811–1817): Following Robert Smith’s resignation, James Monroe, a close ally of Madison and future president himself, was appointed as Secretary of State. Monroe served in this capacity for the remainder of Madison’s presidency and played a significant role in diplomatic affairs, including during the War of 1812.

Secretary of the Treasury:

- Albert Gallatin (1809–1814): Albert Gallatin, a prominent Democratic-Republican politician and fiscal expert, continued in his role as Secretary of the Treasury during Madison’s administration. Gallatin played a key role in managing the nation’s finances during a period of economic uncertainty and the War of 1812.

Secretary of War:

- William Eustis (1809–1813): William Eustis, a physician and military officer, served as Secretary of War during the early years of Madison’s presidency. He oversaw military preparations and operations during the War of 1812 but resigned in 1813 due to criticism of his handling of the conflict.

- John Armstrong Jr. (1813–1814): John Armstrong Jr., a military officer and diplomat, succeeded William Eustis as Secretary of War. His tenure was marked by controversies surrounding military strategy and the burning of Washington, D.C., by British forces in 1814. Armstrong resigned in 1814.

Attorney General:

- Caesar A. Rodney (1809–1811): Caesar A. Rodney, a lawyer and politician from Delaware, served as Attorney General during the early years of Madison’s presidency. He provided legal advice to the administration on various matters, including constitutional issues and legal challenges.

- William Pinkney (1811–1814): William Pinkney, a prominent lawyer and diplomat, succeeded Caesar A. Rodney as Attorney General in 1811. Pinkney’s tenure was marked by his involvement in legal matters related to foreign policy and the War of 1812.

- Richard Rush (1814–1817): Richard Rush, a lawyer and diplomat, became Attorney General in 1814, succeeding William Pinkney. Rush’s tenure saw continued legal challenges and diplomatic efforts to resolve issues arising from the war and its aftermath.

James Madison’s cabinet during his presidency included individuals with diverse backgrounds and expertise, reflecting the various challenges facing the young nation during this critical period in its history. These cabinet members played important roles in shaping Madison’s policies and decisions as he navigated the complexities of domestic and foreign affairs.

The postwar period following the War of 1812 marked a significant transition in American politics, including the decline of the Federalist opposition. Here’s an overview:

Postwar Period and Recovery

Economic Reconstruction:

- The end of the War of 1812 brought economic challenges, including a recession and disruptions to trade and commerce. However, the postwar period also saw a resurgence in economic activity as industries expanded to meet wartime demands.

Territorial Expansion:

- The postwar period witnessed continued westward expansion, with the acquisition of new territories such as Florida (1819) and the Oregon Country (1818). These expansions further fueled economic growth and settlement.

Infrastructure Development:

- The government invested in infrastructure projects such as roads, canals, and bridges to facilitate transportation and trade. The construction of the Erie Canal, completed in 1825, significantly boosted commerce and connectivity between the East Coast and the Midwest.

Decline of the Federalist Opposition

Loss of Political Influence:

- The Federalist Party, which had already been in decline before the war, saw its influence wane further in the postwar period. The party’s opposition to the war and its perceived lack of patriotism contributed to its decline in popularity.

Hartford Convention:

- The Hartford Convention of 1814–1815, where Federalist delegates from New England states discussed their grievances against the war and proposed amendments to the Constitution, further damaged the party’s reputation. The convention’s proposals were seen by many as unpatriotic and seditious.

Election of 1816:

- In the presidential election of 1816, the Federalist Party nominated Rufus King as its candidate, but he was decisively defeated by James Monroe, the Democratic-Republican candidate. Monroe’s victory signaled the end of Federalist influence at the national level.

Shift in Political Landscape:

- The decline of the Federalist Party led to a period of one-party rule dominated by the Democratic-Republicans. This shift in the political landscape marked the beginning of the so-called “Era of Good Feelings,” characterized by a sense of national unity and reduced partisan divisions.

Legacy and Impact

End of Partisan Strife:

- The decline of the Federalist Party contributed to a period of relative political harmony, with the Democratic-Republicans enjoying broad support and dominance in government.

National Identity and Unity:

- The postwar period saw the emergence of a stronger sense of national identity and unity, fueled by the successful defense of American sovereignty during the War of 1812 and the subsequent territorial expansion and economic growth.

Challenges of Sectionalism:

- Despite the decline of the Federalist Party, sectional tensions persisted, particularly between the North and South over issues such as tariffs, internal improvements, and slavery. These tensions would ultimately contribute to the unraveling of the Era of Good Feelings and the rise of new political divisions in the decades that followed.

Overall, the postwar period witnessed significant changes in American politics and society, including the decline of the Federalist Party and the emergence of new challenges and opportunities for the young nation.

The War of 1812 was a significant conflict between the United States and Great Britain that lasted from June 18, 1812, to February 18, 1815. Here’s an overview:

Causes of the War

Maritime Issues:

- Impressment: British impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy was a major point of contention. The British practice of stopping American ships and forcibly recruiting sailors angered many Americans and violated their sense of national sovereignty.

- Interference with Trade: Both Britain and France imposed trade restrictions on American shipping during the Napoleonic Wars, but British actions, including the Orders in Council, were particularly harmful to American commerce.

Native American Resistance:

- British support for Native American resistance to American expansion in the Northwest Territory, notably the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his confederacy, exacerbated tensions. The British provided weapons, supplies, and encouragement to Native American tribes, leading to increased conflict on the frontier.

Nationalism and Expansionism:

- American nationalism was on the rise, fueled by territorial expansion and a desire to assert American sovereignty. War hawks in Congress, particularly from the Western and Southern states, advocated for war as a means to defend American honor and expand U.S. territory.

Major Events and Campaigns

Failed Invasion of Canada (1812):

- The United States launched a three-pronged invasion of Canada in an attempt to seize British territory. However, American forces were unable to achieve significant victories, and the campaign ended in failure.

Naval Battles:

- Despite initial setbacks, the U.S. Navy achieved notable victories against the British Royal Navy, including the USS Constitution’s defeat of HMS Guerriere and the Battle of Lake Erie under the command of Oliver Hazard Perry.

Burning of Washington, D.C. (1814):

- In August 1814, British forces under Admiral George Cockburn and Major General Robert Ross captured Washington, D.C., and set fire to the White House, the Capitol, and other government buildings. This event was a major blow to American morale but did not significantly alter the course of the war.

Battle of New Orleans (1815):

- The final major battle of the war occurred at New Orleans in January 1815, where American forces under General Andrew Jackson decisively defeated a British invasion force. The American victory, though occurring after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, boosted national pride and propelled Jackson to national prominence.

Treaty of Ghent and Aftermath

Treaty of Ghent (1814):

- Negotiations to end the war took place in Ghent, Belgium, resulting in the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814. The treaty restored prewar borders and did not address the major issues that had led to the conflict.

Legacy:

- The War of 1812 ended in a stalemate, but it had significant consequences for both the United States and Great Britain. The war strengthened American nationalism, secured American sovereignty, and marked the end of British support for Native American resistance in the Northwest Territory.

Impact on Canada:

- In Canada, the war is often seen as a victory for Canadian forces who successfully defended against American invasions and preserved Canada’s territorial integrity. The war also contributed to a sense of Canadian national identity separate from Britain.

Overall, the War of 1812 was a pivotal moment in American history, shaping national identity, territorial expansion, and relations with both Great Britain and Canada.

Military actions

During the War of 1812, there were several significant military actions on both land and sea. Here are some of the key ones:

Naval Battles:

- USS Constitution vs. HMS Guerriere (1812):

- The USS Constitution, under the command of Captain Isaac Hull, engaged and defeated the British frigate HMS Guerriere off the coast of Nova Scotia.

- This victory demonstrated the strength of American naval power and boosted morale.

- Battle of Lake Erie (1813):

- Commanded by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, the American fleet defeated the British squadron on Lake Erie.

- Perry’s victory secured control of the lake and facilitated American land campaigns in the region.

- Battle of Lake Champlain (1814):

- American Commodore Thomas Macdonough’s fleet defeated a British squadron on Lake Champlain.

- This victory prevented British forces from advancing into northern New York and contributed to the failure of their invasion plans.

Land Battles:

- Battle of Tippecanoe (1811):

- Fought in present-day Indiana between American forces led by Governor William Henry Harrison and Native American confederacy led by Tecumseh.

- Although not directly part of the War of 1812, it weakened Tecumseh’s alliance with the British and increased tensions leading to the war.

- Battle of Queenston Heights (1812):

- American forces attempted to invade Canada but were repelled by British and Canadian troops.

- Major General Isaac Brock, the British commander, was killed in action, but his forces ultimately secured victory.

- Battle of Fort McHenry (1814):

- British naval forces bombarded Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland, but were unable to capture it.

- The defense of Fort McHenry inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Other Actions:

- Burning of Washington, D.C. (1814):

- British forces, including troops under Admiral George Cockburn and Major General Robert Ross, captured and burned Washington, D.C., including the White House and the Capitol.

- Siege of Fort Meigs (1813):

- American forces, under General William Henry Harrison, successfully defended Fort Meigs in Ohio against British and Native American attacks.

- Battle of New Orleans (1815):

- Fought after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed but before news of the treaty reached America.

- American forces, led by General Andrew Jackson, decisively defeated a British invasion force near New Orleans.

These military actions, along with others, contributed to the outcome of the War of 1812 and influenced subsequent events in American and world history.

Postwar period and decline of the Federalist opposition

Following the War of 1812, the United States entered a postwar period characterized by significant changes in both domestic and foreign affairs. One of the notable developments during this period was the decline of the Federalist opposition. Here’s an overview:

Postwar Period:

- Economic Growth and Expansion:

- The end of the war brought economic opportunities as trade resumed and industries expanded to meet wartime demands.

- Territorial expansion continued, with the acquisition of new territories such as Florida and the Oregon Country.

- Infrastructure Development:

- Government investments in infrastructure projects, including roads, canals, and bridges, improved transportation and facilitated westward expansion.

- The construction of the Erie Canal, completed in 1825, was a significant achievement that boosted commerce and connectivity.

- Nationalism and Unity:

- The successful defense of American sovereignty during the war and territorial gains fueled a sense of national pride and identity.

- The “Era of Good Feelings,” characterized by reduced partisan strife and a spirit of national unity, emerged in the aftermath of the war.

Decline of the Federalist Opposition:

- Loss of Political Influence:

- The Federalist Party, which had opposed the war and faced accusations of disloyalty during the conflict, saw its influence wane.

- The Hartford Convention, where Federalist delegates discussed grievances against the war, further damaged the party’s reputation.

- Election of 1816:

- In the presidential election of 1816, the Federalist Party nominated Rufus King as its candidate, but he was soundly defeated by James Monroe, the Democratic-Republican candidate.

- Monroe’s victory signaled the end of Federalist influence at the national level.

- Shift in Political Landscape:

- With the decline of the Federalist Party, the United States entered a period of one-party rule dominated by the Democratic-Republicans.

- This shift in the political landscape marked the beginning of an era of relative political harmony, at least in terms of partisan divisions.

Legacy and Impact:

- End of Partisan Strife:

- The decline of the Federalist Party contributed to a period of reduced partisan conflict and facilitated the implementation of government policies.

- National Identity and Unity:

- The postwar period saw the emergence of a stronger sense of national identity and unity, which laid the foundation for American expansion and development in the 19th century.

- Challenges of Sectionalism:

- While the decline of the Federalist Party reduced partisan divisions, sectional tensions between the North and South over issues such as tariffs, internal improvements, and slavery continued to simmer and would eventually lead to new political divisions.

Overall, the postwar period and the decline of the Federalist opposition marked a significant turning point in American history, setting the stage for the nation’s growth and development in the years to come.

Native American policy

Native American policy in the United States underwent significant changes throughout its history, influenced by various factors such as territorial expansion, cultural differences, and shifts in government priorities. Here’s an overview of Native American policy from early colonization to the 19th century:

Colonial Period:

- Coexistence and Cooperation:

- Early European settlers often formed alliances and traded with Native American tribes for mutual benefit.

- Some colonies, such as Pennsylvania under William Penn, practiced relatively peaceful coexistence with Native Americans.

- Conflicts and Displacement:

- As European settlements expanded, conflicts over land and resources escalated.

- The Indian Removal Act of 1830, signed into law by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the forced relocation of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands to territories west of the Mississippi River, known as the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

19th Century Policies:

- Treaty-Making Period:

- The U.S. government entered into treaties with Native American tribes to acquire their land in exchange for various promises, such as protection, education, and supplies.

- However, many treaties were unfair and resulted in the loss of Native American lands.

- Indian Removal Act (1830):

- Passed during Andrew Jackson’s presidency, the Indian Removal Act authorized the relocation of Native American tribes from the southeastern United States to Indian Territory.

- The forced removal of tribes, most notably the Cherokee along the Trail of Tears, resulted in immense suffering and loss of life.

- Assimilation Policies:

- The federal government implemented assimilation policies aimed at “civilizing” Native Americans and integrating them into American society.

- The Indian Civilization Fund Act of 1819 provided funding for missionary and educational efforts, including the establishment of Indian boarding schools.

- Reservation System:

- The reservation system, established through treaties and executive orders, allocated specific tracts of land for Native American tribes.

- Reservations were often located in areas deemed undesirable for white settlement and were subject to government control and oversight.

20th Century and Beyond:

- Dawes Act (1887):

- The Dawes Act aimed to assimilate Native Americans by allotting individual parcels of land to tribal members and selling the remaining land to non-Native settlers.

- This policy led to the loss of millions of acres of Native American land and the dissolution of communal land ownership.

- Indian Reorganization Act (1934):

- Also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act, this legislation sought to reverse some of the damaging effects of previous policies by promoting tribal self-government and preserving tribal lands.

- It encouraged the formation of tribal governments and allowed tribes to reacquire lost lands.

- Termination and Self-Determination:

- In the mid-20th century, the federal government pursued a policy of termination, which aimed to end the federal relationship with Native American tribes and assimilate them into mainstream society.

- However, termination policies were largely unsuccessful and were replaced by a policy of tribal self-determination, emphasizing tribal sovereignty and self-governance.

Contemporary Issues:

- Land Rights and Sovereignty:

- Native American tribes continue to advocate for the protection of their land rights and sovereignty, often through legal challenges and political activism.

- Issues such as land disputes, natural resource management, and environmental conservation remain contentious.

- Social and Economic Challenges:

- Many Native American communities face social and economic challenges, including poverty, unemployment, inadequate healthcare, and high rates of substance abuse.

- Efforts to address these issues often involve collaboration between tribal governments, federal agencies, and nonprofit organizations.

Native American policy in the United States has been characterized by a complex and often troubled history, marked by both cooperation and conflict between Native American tribes and the federal government. While progress has been made in recognizing tribal sovereignty and promoting self-determination, challenges persist in addressing the legacy of past injustices and improving the well-being of Native American communities.

In the 1816 presidential election, both former President Thomas Jefferson and outgoing President James Madison supported Secretary of State James Monroe. Monroe secured the Democratic-Republican nomination through a congressional caucus, defeating Secretary of War William H. Crawford. As the Federalist Party weakened, Monroe handily won the general election against Federalist candidate Rufus King, a New York Senator. Madison left office with high approval ratings. Even his predecessor, John Adams, acknowledged Madison’s achievements, claiming he’d achieved “more glory, and established more union, than all his three predecessors combined.

Post-presidency (1817–1836)

The post-presidency period of James Madison, spanning from 1817 to 1836, was marked by his retirement from public office and his continued involvement in political and intellectual pursuits. Here’s an overview of this period:

Retirement from Public Office:

- Return to Montpelier:

- After leaving the presidency in 1817, James Madison retired to his plantation, Montpelier, in Orange County, Virginia.

- He focused on managing his estate, agricultural pursuits, and personal interests.

Political Influence:

- Advisory Role:

- Despite his retirement, Madison remained a respected figure in American politics and continued to be consulted by political leaders for advice and guidance.

- He corresponded with prominent figures of the time and offered insights on various political issues.

Intellectual Pursuits:

- Writing and Scholarship:

- Madison devoted much of his post-presidential years to scholarly pursuits, including writing and research.

- He collaborated with Thomas Jefferson on the establishment of the University of Virginia and served on its Board of Visitors.

- Contribution to the Federalist Papers:

- Madison, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, authored the Federalist Papers during the ratification debates of the U.S. Constitution.

- His contributions to these influential essays solidified his reputation as a leading advocate for constitutional government.

- Correspondence and Publications:

- Madison engaged in extensive correspondence with fellow statesmen, scholars, and friends, discussing a wide range of topics.

- He published several works, including “Notes on the Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787” and “The Federalist Papers.”

Legacy and Impact:

- Recognition as a Founding Father:

- Madison’s contributions to the founding of the United States, including his role in drafting the Constitution and his presidency, earned him recognition as one of the nation’s Founding Fathers.

- His ideas on federalism, separation of powers, and individual rights continue to influence American political thought.

- Death and Memorialization:

- James Madison passed away on June 28, 1836, at Montpelier, at the age of 85.

- He was buried on the estate, and his legacy is commemorated through various memorials, including the James Madison Memorial Building in Washington, D.C., and the James Madison University in Virginia.

James Madison’s post-presidency years were characterized by a blend of retirement, intellectual pursuits, and continued influence on American politics and governance. His contributions to the nation’s founding principles and his enduring legacy as a statesman and scholar continue to be celebrated and studied to this day.

Political and religious views

James Madison, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and the fourth President, held distinctive political and religious views that were influential in shaping American governance and society. Here’s an overview of his political and religious perspectives:

Political Views:

- Federalism:

- Madison was a staunch advocate of federalism, the division of powers between the federal government and the states. He played a key role in drafting the U.S. Constitution, which established a system of checks and balances and delineated the powers of the federal government.

- Republicanism:

- Madison believed in the principles of republicanism, emphasizing the importance of representative government, civic virtue, and the rule of law. He argued for the necessity of balancing majority rule with protections for minority rights to prevent tyranny.

- Limited Government:

- Madison was a proponent of limited government, advocating for constraints on the powers of government to protect individual liberties. He was a primary architect of the Bill of Rights, which enshrined key freedoms such as freedom of speech, religion, and assembly.

- Separation of Powers:

- Madison championed the concept of the separation of powers, dividing governmental authority among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches to prevent the concentration of power in any one branch. His ideas on the separation of powers influenced the structure of the U.S. government.

- Strict Constructionism:

- In interpreting the Constitution, Madison generally adhered to a strict constructionist approach, emphasizing a literal reading of the document and limiting the powers of the federal government to those expressly enumerated in the Constitution.

Religious Views:

- Religious Freedom:

- Madison was a strong advocate for religious freedom and the separation of church and state. He believed that government should not interfere in matters of religion and that individuals should be free to practice their faith without government coercion or support.

- Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom:

- Madison played a significant role in the passage of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786. The statute, drafted by Thomas Jefferson and championed by Madison, disestablished the Anglican Church as the state-supported church in Virginia and guaranteed religious freedom for all citizens.

- Deism:

- Madison’s religious beliefs have been described as consistent with Deism, a philosophical position that emphasizes the existence of a creator or supreme being but rejects traditional religious doctrines, supernatural revelation, and organized religion.

- Private Faith:

- While Madison was not known for publicly expressing his personal religious beliefs, he was a member of the Episcopal Church and attended religious services throughout his life. However, his private faith did not prevent him from advocating for the separation of church and state in public affairs.

James Madison’s political and religious views were deeply informed by Enlightenment ideals, a commitment to individual liberty, and a dedication to the principles of constitutional government. His contributions to American political thought and the development of the U.S. Constitution continue to be studied and revered today.

Slavery

Slavery played a significant and deeply troubling role in American history, including during James Madison’s lifetime. Here’s an overview of how slavery intersected with Madison’s life and political career:

Early Life and Background:

- Montpelier Plantation:

- James Madison was born into a wealthy Virginia family that owned a plantation called Montpelier.

- Like many other plantation owners of his time, Madison grew up in a society where slavery was a central institution, with enslaved laborers working the fields and performing domestic duties.

Political Career and Views on Slavery:

- Constitutional Convention:

- Madison played a pivotal role in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, where delegates grappled with the issue of slavery.

- He was a slaveowner himself but recognized the moral and political complexities of the institution.

- Three-Fifths Compromise:

- Madison supported the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for the purposes of determining representation in Congress and taxation.

- The compromise bolstered the political power of Southern states, where slavery was prevalent.

- Federalist Papers:

- In Federalist No. 54, Madison addressed the issue of slavery, arguing that the three-fifths clause was a necessary compromise to ensure the ratification of the Constitution.

- He acknowledged the injustice of slavery but also sought to reconcile the competing interests of Northern and Southern states.

- Missouri Compromise:

- As President, Madison signed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, preserving the balance between slave and free states in Congress.

- The compromise temporarily defused tensions over the expansion of slavery into new territories.

Later Years and Legacy:

- Evolution of Views:

- Over time, Madison’s views on slavery evolved, and he became more critical of the institution.

- In his later years, he expressed regret over the compromises made during his political career that perpetuated the institution of slavery.

- Legacy and Impact:

- While Madison made significant contributions to American political thought and governance, his legacy is complicated by his ownership of enslaved individuals and his role in shaping policies that upheld and perpetuated slavery.

- However, he also recognized the inherent contradictions between the principles of liberty and the institution of slavery, contributing to ongoing debates over the complexities of America’s founding ideals.

James Madison’s life and political career reflect the deep entrenchment of slavery in American society during the early republic and the challenges of reconciling the nation’s founding principles with the realities of a slaveholding society.

History

James Madison grew up on Montpelier, his family’s Virginia plantation that relied on slave labor like many others in the South. When he left for college in 1769, he brought a slave named Sawney to handle finances and communication with his family. Fearing a slave rebellion in 1783, Madison freed one slave, Billey, but then sold him into a seven-year apprenticeship. Billey, who later became William Gardner, thrived after his manumission, even working as Madison’s shipping agent in Philadelphia, before tragically drowning in 1795.

Madison inherited Montpelier and its over 100 slaves after his father’s death in 1801. He became Secretary of State that same year and relocated to Washington D.C., managing Montpelier from afar without freeing any slaves. He even brought slaves with him when he became President in 1808. Later, during the 1820s and 1830s, he sold some land and slaves to settle debts. By the time he died in 1836, Madison still owned 36 slaves according to tax records. In his will, he instructed his wife Dolley not to sell the slaves without their consent, but she was forced to do so anyway to pay off debts.

Treatment of slaves

James Madison, reflecting the social norms of Virginia at the time, advocated for humane treatment of his slaves at Montpelier. His farm papers show him instructing an overseer to treat them with “humanity and kindness,” while ensuring they had milk and proper meals. By the 1790s, some slaves like Sawney, who could even read, held positions of responsibility overseeing parts of the plantation. Work schedules involved six days a week with a break and Sundays off.

One enslaved person, Paul Jennings, served as Madison’s footman for nearly five decades. In his memoir, Jennings recounted never witnessing Madison or overseers striking slaves. Though a house slave given a basic education and even learning music, Jennings condemned slavery but viewed James and Dolley as kind individuals.pen_sparktunesharemore_vert

Views on slavery

James Madison spoke out against slavery, calling it the “most oppressive dominion” and expressing lifelong abhorrence for it. He even supported a bill for gradual abolition in Virginia and opposed measures to restrict individual slave manumission. Yet, as a slave owner himself, Madison grappled with this inconsistency throughout his career. Historians acknowledge his strong anti-slavery principles but also note the pragmatic compromises he made to maintain national unity.

While not subscribing to racial inferiority views, Madison believed peaceful coexistence between Black and white people was unlikely due to societal prejudices. He therefore supported the idea of freed slaves establishing colonies in Africa, even leading the American Colonization Society for Liberia. Though a long-term solution, Madison saw this as a way to eventually eradicate slavery in the US. He still held out hope for eventual peaceful coexistence between the races.

Despite initial opposition, Madison accepted the 20-year protection of the slave trade as a compromise to get the South on board with the Constitution. He also played a role in the Three-fifths Compromise. During the Missouri crisis, Madison supported allowing slavery to expand westward, arguing it wouldn’t increase the slave population but improve conditions and lead to more gradual emancipation. However, some historians argue that Madison’s personal dependence on slavery ultimately weakened his anti-slavery convictions.

Legacy and Historical reputation

James Madison left a profound legacy in American history, shaped by his pivotal role in the founding of the United States, his leadership as the fourth President, and his contributions to the development of American political thought. Here’s an overview of his legacy and historical reputation:

Legacy:

- Architect of the Constitution:

- Madison’s contributions to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 were instrumental in shaping the U.S. Constitution.

- He played a central role in drafting the Constitution, advocating for a strong federal government with checks and balances and protections for individual rights.

- Father of the Bill of Rights:

- Madison’s advocacy for a bill of rights led to the inclusion of the first ten amendments to the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights.

- His commitment to protecting individual liberties and limiting the powers of government has had a lasting impact on American governance.

- Leadership during the War of 1812:

- As President during the War of 1812, Madison provided steady leadership in the face of significant challenges, including British invasion and the burning of Washington, D.C.

- Despite initial setbacks, his administration ultimately secured American sovereignty and territorial integrity.

- Contributions to Political Thought:

- Madison’s writings, including the Federalist Papers, have had a profound influence on American political thought.

- His ideas on federalism, separation of powers, and individual rights continue to shape debates over the nature of American government and democracy.

Historical Reputation:

- Founding Father and Statesman:

- James Madison is widely regarded as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and a key architect of American democracy.

- His contributions to the founding of the nation, including his role in drafting the Constitution and promoting the Bill of Rights, have earned him a prominent place in American history.

- Legacy of Compromise and Pragmatism:

- Madison’s willingness to compromise, as seen in his efforts to reconcile competing interests at the Constitutional Convention and during his presidency, has been both praised and criticized.

- Some view his pragmatic approach as essential to the success of American governance, while others see it as a compromise of principles.

- Complexity of Views on Slavery:

- Madison’s legacy is complicated by his ownership of enslaved individuals and his role in shaping policies that perpetuated slavery.

- While he recognized the injustice of slavery and sought to limit its expansion, his actions fell short of fully confronting the institution.

- Enduring Influence:

- Despite the complexities of his legacy, Madison’s ideas on government, liberty, and democracy continue to resonate in American politics and society.

- His emphasis on the importance of a well-structured government and protections for individual rights remains relevant to contemporary debates over governance and constitutional interpretation.

James Madison’s legacy reflects the complexities and contradictions of American history, embodying both the nation’s highest ideals and its enduring challenges. As a Founding Father and statesman, his contributions to American democracy continue to be studied, debated, and celebrated to this day.

Popular culture

James Madison’s influence and contributions to American history are often depicted or referenced in various forms of popular culture, including literature, film, television, and music. While he may not be as prominently featured as some other Founding Fathers, such as George Washington or Thomas Jefferson, Madison’s role in shaping the nation has not gone unnoticed. Here are some examples of how James Madison has been represented in popular culture:

Literature:

- Historical Fiction:

- Madison is a common character in historical fiction novels that explore the early years of the United States and the lives of its Founding Fathers.

- Authors such as Gore Vidal, David McCullough, and Ralph K. Andrist have featured Madison in their works of historical fiction and non-fiction.

Film and Television:

- Biographical Films:

- While there are fewer films specifically focused on James Madison compared to other Founding Fathers, he is often depicted in films about the Revolutionary War era or the early years of the United States.

- Documentaries and biographical films sometimes feature reenactments or portrayals of Madison’s life and political career.

Music: