George Washington legacy (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was an American Founding Father and the first president of the United States (1789-1797). Appointed as the Continental Army’s commander in 1775, he led the Patriots to victory in the Revolutionary War. He later presided over the Constitutional Convention in 1787, establishing the U.S. federal government. Washington is often called the “Father of his Country”.

Starting as a surveyor in 1749, Washington gained military experience in the French and Indian War. Elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, he later became a delegate to the Continental Congress, which named him commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. After winning the war and securing U.S. independence with the Treaty of Paris, he resigned his military commission in 1783.

Washington was pivotal in drafting and ratifying the Constitution, replacing the Articles of Confederation. Elected president unanimously, he established a strong national government, remained neutral during the French Revolution, and set key presidential precedents, including the two-term limit. His 1796 farewell address emphasized national unity and warned against regionalism, partisanship, and foreign alliances.

Washington’s legacy is celebrated through monuments, a federal holiday, and numerous depictions in culture and currency. He was posthumously promoted to general of the Armies in 1976 and is consistently ranked among the greatest U.S. presidents.

Early Life (1732–1752)

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, as the first child of Augustine and Mary Ball Washington. His father, a justice of the peace, had four children from a previous marriage. The family moved several times, eventually settling at Ferry Farm near Fredericksburg, Virginia. Upon Augustine’s death in 1743, Washington inherited Ferry Farm and ten slaves, while his half-brother Lawrence inherited and renamed Little Hunting Creek to Mount Vernon.

Washington’s education was informal; he attended the Lower Church School in Hartfield, learning mathematics and land surveying. As a teenager, he copied rules of etiquette, honing his penmanship. He frequently visited Mount Vernon and Belvoir, the plantation of Lawrence’s father-in-law, William Fairfax, who became his mentor. In 1748, Washington helped survey Fairfax’s Shenandoah Valley land and, in 1749, became the surveyor of Culpeper County, Virginia.

By 1752, Washington had acquired substantial landholdings in the Shenandoah Valley. In 1751, he traveled to Barbados with Lawrence, who was seeking a cure for tuberculosis. Washington contracted smallpox during the trip, leaving him with facial scars. After Lawrence’s death in 1752, Washington leased Mount Vernon and inherited it in 1761.

Colonial Military Career (1752–1758)

Inspired by his half-brother Lawrence, George Washington sought a military career and was appointed by Virginia’s lieutenant governor, Robert Dinwiddie, as a major and commander of one of the colony’s four militia districts. At the time, the British and French were vying for control of the Ohio Valley.

In October 1753, Dinwiddie sent Washington as a special envoy to demand the French vacate British-claimed land and to make peace with the Iroquois Confederacy. Washington met with Iroquois chiefs, including Half-King Tanacharison, at Logston and gathered crucial intelligence on French forts. Tanacharison nicknamed Washington “Conotocaurius,” meaning “devourer of villages,” a name given to his great-grandfather by the Susquehannock.

Washington’s party reached the Ohio River in November 1753 and was escorted by a French patrol to Fort Le Boeuf. Despite being received warmly, the French commander Saint-Pierre refused to vacate. After a few days, Washington received Saint-Pierre’s official refusal, along with provisions for the return journey. Washington’s successful completion of this 77-day mission during harsh winter conditions earned him recognition when his report was published in Virginia and London.

- 1st President of the United States

- 2nd President of the United States

- 3rd President of the United States

- 4th President of the United States

- 5th President of the United States

- 6th President of the United States

- 7th President of the United States

- 8th President of the United States

- 9th President of the United States

- 10th President of the United States

- 11th President of the United States

- 12th president of the United States

- 13th President of the United States

Main article: George Washington in the French and Indian War

In February 1754, Robert Dinwiddie promoted George Washington to lieutenant colonel and second-in-command of the 300-strong Virginia Regiment, tasked with confronting French forces at the Forks of the Ohio. Washington set out in April, discovering that the French were building Fort Duquesne with a force of 1,000 men. In May, he established a defensive position at Great Meadows and learned of a nearby French camp.

On May 28, Washington, with a small group of Virginians and Indian allies, ambushed the French detachment of about 50 men, killing several, including the commander, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. The French accused Washington of the attack and retreated to Fort Necessity.

In June, Washington was promoted to colonel after the regiment’s commander died. He clashed with Captain James Mackay, whose royal commission outranked Washington’s. On July 3, a French force of 900 attacked Fort Necessity, forcing Washington to surrender. He unknowingly signed a document taking responsibility for Jumonville’s death, later blaming a translation error.

Colonel James Innes then took command of the intercolonial forces, and Washington, refusing a demotion to captain, resigned. This “Jumonville affair” sparked the French and Indian War, part of the larger Seven Years’ War.

French and Indian War Service (1755–1758)

In 1755, George Washington volunteered as an aide to General Edward Braddock in a British expedition to drive the French from Fort Duquesne. Following Washington’s advice, Braddock divided his forces, but Washington, suffering from dysentery, had to stay behind. He rejoined Braddock at Monongahela just as the French and their Indian allies ambushed the army. The attack left two-thirds of the British force dead or wounded, including Braddock. Despite his illness, Washington rallied the survivors, forming a rear guard to cover their retreat. He had two horses shot from under him and bullet holes in his hat and coat, actions that redeemed his reputation after the Battle of Fort Necessity.

In August 1755, Washington was appointed commander of the reconstituted Virginia Regiment with the rank of colonel. He faced immediate conflicts over seniority, particularly with Captain John Dagworthy. Washington sought a royal commission, arguing his case to successive commanders, but was ultimately refused. However, he was relieved of manning Fort Cumberland.

In 1758, Washington joined the British Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne, disagreeing with General John Forbes’ tactics. Forbes made Washington a brevet brigadier general and gave him command of a brigade. By the time they reached Fort Duquesne, the French had abandoned it, and Washington’s only engagement was a friendly fire incident with casualties. Frustrated, he resigned and returned to Mount Vernon.

Under Washington’s command, the Virginia Regiment defended 300 miles of frontier against numerous attacks, improving its professionalism and reducing the impact on Virginia’s population compared to other colonies. Although he never received a royal commission, Washington gained valuable leadership skills, military knowledge, and a perspective that later influenced his support for a strong central government.

Marriage, Civilian, and Political Life (1755–1775)

On January 6, 1759, 26-year-old George Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow one year his senior. The marriage, held at Martha’s estate, was happy and brought Washington considerable wealth and social standing. They moved to Mount Vernon, where Washington became a prominent planter and political figure.

Although smallpox likely rendered Washington sterile, and Martha may have had complications from childbirth, the couple raised Martha’s two children, Jacky and Patsy, and later Jacky’s two youngest children, Nelly and Washy, along with several nieces and nephews.

The marriage gave Washington control over Martha’s dower share of the Custis estate, making him one of Virginia’s wealthiest men. He managed both his and Martha’s land, including the slaves on the estate. By 1775, he had expanded Mount Vernon significantly.

Washington became a local leader and was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, representing Frederick County for seven years. Initially quiet in his legislative role, he became a vocal critic of British policies in the 1760s.

Financially strained by low tobacco prices and lavish spending, Washington switched Mount Vernon’s main crop from tobacco to wheat in 1765, diversifying into milling and fishing. This helped stabilize his finances.

From 1768 to 1775, Washington hosted about 2,000 guests at Mount Vernon, cementing his place among Virginia’s elite. He enjoyed leisure activities such as fox hunting, fishing, dancing, and playing cards.

In 1773, Washington’s stepdaughter Patsy died from epilepsy, a loss that deeply affected him. He took three months off from his responsibilities to support Martha through their shared grief.

Opposition to the British Parliament and Crown

George Washington played a crucial role in the events leading to the American Revolution. His distrust of the British began when he was denied a promotion to the Regular Army. Like many colonists, Washington opposed the taxes imposed by the British Parliament without representation and was angered by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which restricted American settlement west of the Alleghenies.

Washington viewed the Stamp Act of 1765 as oppressive and celebrated its repeal in 1766. However, Parliament’s Declaratory Act, which asserted that British law superseded colonial law, continued to fuel discontent. Washington, a successful land speculator, was particularly upset by British interference in western land speculation.

In the late 1760s, he helped lead protests against the Townshend Acts, which imposed taxes on various goods. In 1769, he proposed a boycott of British goods, which contributed to the Acts’ partial repeal in 1770.

When Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in 1774 to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party, Washington saw it as an invasion of colonial rights. He believed Americans should resist tyranny and, alongside George Mason, drafted resolutions for the Fairfax County committee calling for an end to the Atlantic slave trade.

In August 1774, Washington attended the First Virginia Convention and was chosen as a delegate to the First Continental Congress. As tensions escalated, he trained Virginia militias and enforced the boycott of British goods.

The American Revolutionary War began on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Upon hearing the news, Washington was deeply moved and quickly left Mount Vernon on May 4, 1775, to join the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

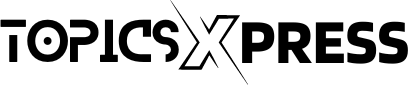

Commander in Chief (1775–1783)

On June 14, 1775, Congress established the Continental Army and appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief, believing his military experience and Virginian background would unify the colonies. Washington accepted the role on June 16, declining a salary but later being reimbursed for expenses. He officially took command on June 19 and was tasked with leading the Siege of Boston on June 22.

Congress selected key staff officers for Washington, including Major Generals Artemas Ward, Horatio Gates, Charles Lee, Philip Schuyler, and Nathanael Greene. Henry Knox, noted for his ordnance expertise, became chief of artillery, and Alexander Hamilton, admired for his intelligence and bravery, was appointed Washington’s aide-de-camp.

Initially, Washington banned the enlistment of black soldiers. However, as the British offered freedom to slaves who joined their ranks, and facing a shortage of troops by late 1777, he reversed this decision. By the end of the war, about 10% of his army consisted of black soldiers.

After the British surrender, Washington attempted to reclaim slaves freed by the British, but British commander Sir Guy Carleton issued freedom certificates, allowing many former slaves to leave with the British in late 1783.

Siege of Boston

In early 1775, British troops led by General Thomas Gage occupied Boston, fortifying the city. Local militias surrounded and trapped the British forces, resulting in a prolonged standoff.

Boston and New York

Upon his arrival in Boston in July 1775, George Washington took command of the Continental Army and immediately set about imposing discipline and organization. He secured the heights of Dorchester, forcing the British to evacuate Boston in March 1776.

Moving to New York City, Washington anticipated British retaliation and fortified the area. Despite outnumbering his troops, he aimed to defend the city. The British, led by General Howe, landed on Staten Island and began the siege. After the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, Washington informed his troops of the colonies’ independence.

In the Battle of Long Island, Washington’s forces suffered heavy losses, prompting a retreat across the East River to Manhattan. Despite losing Fort Washington and facing criticism for his decisions, Washington managed a strategic withdrawal to New Jersey.

Howe’s pursuit forced Washington to retreat further, crossing the Hudson River to Fort Lee. Howe captured Fort Washington, but Washington, now with a depleted army, evaded further confrontation and retreated through New Jersey.

Despite setbacks, Washington’s leadership and ability to preserve his forces during retreats demonstrated his resilience and strategic acumen.

Continental Congress and the Declaration of Independence

Upon his arrival in Boston in July 1775, George Washington took command of the Continental Army and immediately set about imposing discipline and organization. He secured the heights of Dorchester, forcing the British to evacuate Boston in March 1776.

Moving to New York City, Washington anticipated British retaliation and fortified the area. Despite outnumbering his troops, he aimed to defend the city. The British, led by General Howe, landed on Staten Island and began the siege. After the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, Washington informed his troops of the colonies’ independence.

In the Battle of Long Island, Washington’s forces suffered heavy losses, prompting a retreat across the East River to Manhattan. Despite losing Fort Washington and facing criticism for his decisions, Washington managed a strategic withdrawal to New Jersey.

Howe’s pursuit forced Washington to retreat further, crossing the Hudson River to Fort Lee. Howe captured Fort Washington, but Washington, now with a depleted army, evaded further confrontation and retreated through New Jersey.

Despite setbacks, Washington’s leadership and ability to preserve his forces during retreats demonstrated his resilience and strategic acumen.

Crossing the Delaware and Trenton

Facing dwindling supplies and harsh winter conditions, George Washington embarked on a daring plan to attack Hessian troops stationed at Trenton. Crossing the icy Delaware River on Christmas night in 1776, his troops endured extreme weather to launch a surprise assault. Despite logistical challenges and adverse conditions, Washington’s strategy paid off as they overwhelmed the enemy, securing a crucial victory.

After the triumph at Trenton, Washington’s forces engaged British regulars at Princeton, where they achieved another significant win. Despite suffering losses, Washington’s leadership inspired a decisive counterattack, compelling the British to retreat to New York City. Establishing winter headquarters in Morristown, New Jersey, Washington bolstered Patriot morale and disrupted British supply lines, setting the stage for further successes.

Philadelphia and Saratoga

In July 1777, British General Burgoyne’s advance in upstate New York threatened to divide New England. Meanwhile, General Howe’s decision to march on Philadelphia exposed Patriot vulnerabilities. Despite initial setbacks at Brandywine and Germantown, Washington remained vigilant, sending reinforcements to confront Burgoyne.

At Saratoga, Burgoyne’s defeat shifted momentum in favor of the Patriots, securing a vital victory that bolstered Washington’s strategic position. Although facing criticism and waning admiration, Washington’s resilience and leadership during these campaigns demonstrated his unwavering commitment to the Patriot cause.

Valley Forge

In the harsh winter of 1777, George Washington and his Continental Army endured immense suffering at Valley Forge. Amidst disease, hunger, and exposure, they faced a significant loss of troops. Despite these hardships, Washington’s leadership remained resolute as he petitioned Congress for much-needed provisions. His perseverance, coupled with the drilling efforts of Baron von Steuben, transformed the army into a disciplined fighting force by the camp’s end.

Monmouth

As spring arrived, Washington faced a new challenge when the British evacuated Philadelphia for New York. Summoning a war council, he devised a plan to engage the retreating enemy at the Battle of Monmouth. Despite initial setbacks caused by missteps from General Lee and Lafayette, Washington rallied his troops to achieve a draw. The British continued their retreat, marking Monmouth as Washington’s final battle in the North.

West Point Espionage

Under Major Benjamin Tallmadge’s leadership, the Culper Ring was established at Washington’s behest to gather intelligence on British activities in New York. Despite Benedict Arnold’s previous successes, his grievances and financial troubles led him to betray Washington’s trust. Arnold supplied British spymaster John André with critical information aimed at compromising Washington’s plans and capturing West Point. When André was captured with the plans, Arnold fled, and Washington took immediate measures to safeguard the fort and thwart further treachery.

Southern Theater and Yorktown

In the Southern theater, General Clinton’s invasion of Georgia sparked conflict, while Washington dealt with internal threats and harsh winter conditions. Despite setbacks, including the devastation of the Iroquois and defeats in the South, Washington persevered. With French support, he orchestrated a strategic shift to focus on Cornwallis in Virginia. The siege of Yorktown marked a turning point, with Washington’s leadership securing a decisive victory that ultimately led to the end of the war. The subsequent Treaty of Paris solidified American independence, concluding the long and arduous struggle for freedom

Demobilization and Resignation

As peace negotiations unfolded in 1782, both British and French forces began withdrawing, leaving the American treasury depleted and soldiers unpaid. Washington intervened to quell the Newburgh Conspiracy, a potential mutiny among officers, securing promises of bonuses from Congress. He also settled his own substantial expenses incurred during the war.

In August 1783, Washington presented his vision for a peacetime military to Congress, advocating for a standing army, a national militia, and the establishment of a navy and military academy. With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in September, officially recognizing American independence, Washington disbanded his army and bid farewell to his troops in November.

Overseeing the evacuation of British forces in New York, Washington received acclaim and formal possession of the city. He then bid farewell to his officers at Fraunces Tavern before resigning as commander-in-chief in a poignant statement to Congress. His resignation was hailed as a testament to the stability of the fledgling republic, and he was appointed president-general of the Society of the Cincinnati, a role he held until his death.

Return to Mount Vernon

Upon his return to Mount Vernon, George Washington found solace in the quietude of home after years of wartime and public service. Despite the warm welcome and celebrity status, he faced the harsh reality of financial strain. Mount Vernon, his estate, had not fared well during his absence, plagued by poor crop yields, depreciated wartime currency, and mounting debts.

Undeterred, Washington threw himself into revitalizing Mount Vernon. He oversaw extensive remodeling projects, transforming his residence into the iconic mansion it is today. Additionally, he embarked on ambitious agricultural endeavors, experimenting with new techniques to improve crop yields and diversify the estate’s produce.

One notable project was his venture into mule breeding, sparked by a gift from King Charles III of Spain. Recognizing the potential of mules for agriculture and transportation, Washington saw this endeavor as a means to revolutionize farming practices in the young nation.

Despite the financial challenges, Washington remained resolute in his determination to make Mount Vernon profitable once again. He implemented innovative landscaping plans, cultivated fast-growing trees and native shrubs, and explored new avenues for economic growth on his estate. Through his dedication and perseverance, Washington sought to secure the financial future of Mount Vernon while enjoying the tranquility of private life.

Constitutional Convention of 1787

After retiring from public life, George Washington continued to advocate for a stronger union, expressing concerns about the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. He believed that without a more robust central government, the nation was vulnerable to chaos and foreign intervention. When events like Shays’ Rebellion highlighted the deficiencies of the existing system, Washington became even more convinced of the need for a national constitution.

Washington’s leadership was pivotal in convening the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Despite initially declining to lead the Virginia delegation, he ultimately agreed, recognizing the importance of his presence in securing broad support for the convention and the eventual ratification of the Constitution. Elected unanimously as president of the convention, Washington presided over the deliberations and lent his prestige to the arduous task of drafting a new constitution.

Despite his reservations about the outcome, Washington remained committed to the process and worked tirelessly to encourage delegates to support the Constitution. While the final version was not without controversy, Washington’s advocacy played a crucial role in its eventual adoption by the states.

Chancellor of William & Mary

In 1788, Washington was elected Chancellor of the College of William & Mary, a position he accepted with humility and dedication. Serving until his death in 1799, Washington’s association with the college reflected his commitment to education and public service.

First Presidential Election

Washington’s leadership during the Constitutional Convention led many to anticipate his election as the first President of the United States. Following his unanimous election by state electors, Washington reluctantly left Mount Vernon to assume the presidency in New York City. Despite his apprehensions, he embraced the responsibility with characteristic humility and determination, setting the stage for his historic presidency.

Presidency (1789–1797)

Main article: Presidency of George Washington

Inauguration and Early Actions George Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York City, taking the oath of office administered by Chancellor Robert R. Livingston. He emphasized national unity in his inaugural address and reluctantly accepted a presidential salary set by Congress. Washington set precedents for the office, preferring the title “Mr. President” and establishing executive traditions such as the inaugural address and cabinet system.

Presidential Term and Political Climate Washington initially planned to retire after one term but was persuaded to remain in office due to political strife. He maintained a non-partisan stance, though his administration faced challenges from rival factions led by Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Despite personal reservations, Washington supported Hamilton’s financial program, leading to the formation of the Federalist and Republican parties.

Cabinet and Executive Departments Washington appointed key figures to executive departments, including Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State and Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury. His cabinet became a forum for debate and policy formulation, with Hamilton and Jefferson representing opposing viewpoints on matters such as national debt and federal power.

Domestic Issues Washington exercised restraint in using his veto power and proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving in 1789 to promote national unity. However, his administration faced contentious issues such as slavery, with Washington signing measures that reinforced the institution while also enacting legislation limiting the Atlantic slave trade and admitting free states to the Union.

African Americans Despite some measures to limit slavery’s expansion, Washington signed laws that perpetuated the institution, including the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. He also oversaw the admission of slave states to the Union and faced opposition from free blacks who feared the law would lead to kidnapping and bounty hunting.

National Bank

During Washington’s first term, economic issues took center stage. Alexander Hamilton, his Secretary of the Treasury, faced the challenge of establishing public credit. After Congress reached a deadlock, a compromise was brokered in 1790: Hamilton’s debt proposals were accepted in exchange for temporarily relocating the capital to Philadelphia and then to a site near Georgetown on the Potomac River.

However, one contentious issue arose when Hamilton advocated for the creation of the First Bank of the United States. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison opposed the idea, arguing that it exceeded the government’s constitutional authority. Despite their objections, Congress passed legislation to establish the bank, which Washington signed into law in 1791.

A financial crisis ensued in March 1792, as Hamilton’s Federalists took advantage of large loans, leading to a run on the national bank. Although the markets eventually stabilized, Jefferson suspected Hamilton of involvement in the crisis, exacerbating tensions between the two factions.

Jefferson–Hamilton Feud

Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton held starkly contrasting political beliefs, with Hamilton advocating for a strong central government supported by measures like a national bank and foreign loans, while Jefferson favored a decentralized government led by states and agrarian interests, opposing banks and foreign borrowing. Their differences led to persistent disputes and infighting, much to Washington’s dismay.

Tensions escalated to the point where Hamilton demanded Jefferson’s resignation if he couldn’t support Washington, while Jefferson warned Washington of Hamilton’s fiscal policies potentially leading to the downfall of the republic. Despite Washington’s attempts to mediate, the two men continued their feud.

Jefferson’s support of the National Gazette and efforts to undermine Hamilton almost prompted Washington to dismiss him from the cabinet. Eventually, Jefferson resigned from his position in December 1793, with Washington distancing himself from him.

The feud between Jefferson and Hamilton contributed to the formation of the Federalist and Republican parties, with party affiliation becoming crucial for congressional elections by 1794. While Washington remained neutral in public, he privately held Hamilton in high regard, even amid the scandal surrounding Hamilton’s affair with Maria Reynolds.

Whiskey Rebellion

In response to an excise tax on distilled spirits imposed by Congress in 1791, protests erupted among grain farmers in Pennsylvania’s frontier districts, who felt overburdened by debt and taxation. Despite Washington’s initial reluctance to resort to force, escalating threats and violence led to the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794.

Washington issued proclamations urging peace but ultimately called upon state militias to quell the rebellion when peaceful resolutions failed. Troops, commanded initially by Washington and later by Henry Lee, dispersed the rebels, taking 150 prisoners. Washington’s decision to pardon two condemned rebels demonstrated the federal government’s authority while upholding the rule of law.

This decisive action marked the first use of federal military force against citizens and affirmed the government’s ability to protect its interests and enforce its laws.

Foreign Affairs

In response to the French Revolutionary Wars, Washington declared American neutrality in 1792. However, the arrival of French diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt and his efforts to promote France’s interests in America prompted Washington to demand his recall.

Meanwhile, Hamilton negotiated the Jay Treaty with Britain to normalize trade relations and resolve outstanding debts from the Revolution. Although the treaty faced criticism, Washington supported it to avoid war with Britain, despite its provisions being perceived as favoring Britain. The treaty secured peace and prosperous trade for a decade but strained relations with France, setting the stage for potential conflict.

Native American Affairs

Washington faced challenges in dealing with Native American tribes in the Northwest frontier, exacerbated by British refusal to evacuate forts and their encouragement of Indian attacks on American settlers. Despite efforts to negotiate treaties and conciliate with tribes, conflicts persisted.

The Treaty of New York in 1790, negotiated with Creek Chief Alexander McGillivray, aimed to pacify raiding Indian tribes in the Southwest. However, military efforts led by Brigadier General Josiah Harmar and later by Major General Arthur St. Clair ended in defeat against tribes led by Miami chief Little Turtle.

Washington then appointed Anthony Wayne to lead the forces. Under Wayne’s leadership, the American army achieved victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. The subsequent Treaty of Greenville in 1795 opened up significant territories for American settlement, marking a turning point in Native American relations.

Second Term

Despite initial reluctance, Washington was persuaded to run for a second term, which he won unanimously in 1793. He faced challenges such as maintaining neutrality during the French Revolutionary Wars and dealing with diplomatic troublemakers like Edmond-Charles Genêt.

His second term saw the resignations of key cabinet members, including Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. Washington faced criticism from political foes and a partisan press, but his retirement at the end of his second term set a precedent for peaceful transitions of power in the young republic.

Farewell Address

In 1796, George Washington decided not to seek a third term as president. Before retiring, he penned his Farewell Address with the help of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. Published in September 1796, the address emphasized the importance of national unity and warned against the dangers of regionalism, political partisanship, and foreign entanglements.

Washington stressed the significance of American identity, urging citizens to prioritize the interests of the nation over sectional or party allegiances. He cautioned against forming permanent alliances with foreign powers and advocated for a policy of neutrality in European conflicts.

Additionally, Washington highlighted the importance of religion and morality in maintaining a stable republic. He reflected on his time in office, acknowledging the possibility of errors and expressing hope for the nation’s future prosperity.

Although initially criticized by some for its perceived pro-British stance, Washington’s Farewell Address has since been recognized as a seminal statement on republican principles and received widespread acclaim for its enduring wisdom and guidance.

Post-presidency (1797–1799)

After retiring to Mount Vernon in 1797, George Washington focused on managing his plantations and business interests. Despite minimal profitability, he remained committed to his Federalist ideals and supported measures such as the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Restlessness set in as tensions with France escalated, leading to the “Quasi-War” and French privateers seizing American ships. Washington offered to organize President Adams’ army and was appointed commanding general in 1798.

During his brief tenure, Washington delegated active leadership to Alexander Hamilton and focused on strategic planning. He also pursued ventures like a whiskey distillery to supplement his income and invested in land development around the new Federal City.

Though perceived as wealthy due to Mount Vernon’s grandeur, much of Washington’s wealth was tied up in land and slaves. Despite financial challenges, he continued to play a significant role in shaping the nation’s early military and economic landscape until his death in 179.

Final Days and Death

In his final days, George Washington’s health took a sudden turn. After a long day inspecting his farms, he returned home, disregarding his damp clothes and hosting dinner guests. The next morning, a sore throat developed, escalating quickly to chest congestion and difficulty breathing. Despite his worsening condition, Washington maintained his composure.

Summoning doctors, he endured the common medical practices of the time, including bloodletting. As his condition deteriorated, doctors debated the severity of his illness, but Washington remained resolute. Facing death with characteristic bravery, he reassured his physician, expressing his acceptance of his fate.

As the end drew near, Washington’s concern for being buried alive led him to instruct his secretary to delay his interment. Surrounded by loved ones, he passed away peacefully, leaving behind a grieving nation.

Congress mourned his passing, and the nation came together to honor his memory. His funeral at Mount Vernon was a solemn affair, attended by family, friends, and dignitaries. Church bells tolled across the land, marking the loss of a revered leader.

The cause of Washington’s death has been the subject of much speculation, but it is widely believed that his illness, exacerbated by the medical treatments of the time, led to his untimely demise. Despite the passage of centuries, his legacy endures, a testament to his leadership and sacrifice for the young nation.

Burial, net worth, and aftermath

After his passing, George Washington found his final resting place in the family vault at Mount Vernon. His estate, valued at $780,000 in 1799, reflected his considerable wealth, which included vast land holdings and hundreds of enslaved individuals. At its peak, his net worth was an impressive $587 million, making him one of the wealthiest men of his time.

In the years following his death, attempts were made to steal what was believed to be Washington’s skull, prompting the construction of a more secure vault. Washington himself had anticipated the need for a new resting place, as the old family vault was in disrepair even before his passing. Thus, a new vault was erected at Mount Vernon to house the remains of George and Martha, along with other relatives.

Controversy arose in 1832 when a proposal was made to relocate Washington’s body to a crypt in the United States Capitol. Southern opposition was fierce, reflecting the growing tensions between North and South. Concerns were voiced about the possibility of Washington’s remains being moved to foreign soil if the nation became divided, ultimately leading to the decision to keep him at Mount Vernon.

In 1837, George Washington’s remains were placed in a marble sarcophagus designed by William Strickland and constructed by John Struthers. This sarcophagus, along with Martha’s, resides within an outer vault, surrounded by the remains of other family members. Thus, even in death, Washington remains a central figure in American history, honored and remembered for his leadership and contributions to the nation.

Personal life

George Washington, though reserved in demeanor, possessed a commanding presence that left a lasting impression on those around him. Standing taller than most, with varying accounts placing his height between 6 feet and 6 feet 3.5 inches, he was a figure of strength and stature. His piercing grey-blue eyes and long, reddish-brown hair, meticulously curled and powdered in the fashion of the time, added to his distinctive appearance.

Despite his imposing stature, Washington struggled with health issues, particularly severe tooth decay that eventually led to the loss of all but one of his teeth. Contrary to popular belief, his false teeth were not wooden but made from a combination of metals, ivory, bone, and even human teeth, possibly obtained from enslaved individuals. This constant source of pain led him to rely on laudanum for relief.

Beyond his physical presence, Washington possessed diverse talents and interests. Renowned as a skilled horseman, he had a fondness for collecting thoroughbred horses and was known for his favorites, Blueskin and Nelson. His pursuits also included fox hunting, deer stalking, and attending the theater, where he displayed his gracefulness on the dance floor. Despite enjoying alcohol in moderation, he held strong moral convictions against excessive drinking, smoking, gambling, and profanity.

In all aspects of his life, George Washington embodied a sense of dignity, strength, and moral integrity that left an indelible mark on American history.

Religious and spiritual views

George Washington’s religious and spiritual beliefs were deeply rooted in his upbringing and personal convictions. Descended from Anglican minister Lawrence Washington, he was baptized into the Anglican Church as an infant and remained a devoted member throughout his life. Washington’s faith was not merely a private matter; he actively participated in religious life, serving in various roles within Anglican parishes and publicly encouraging prayer and spiritual reflection.

His conception of God was characterized by a belief in a wise and active Creator, contrary to the deistic views prevalent during his time. Washington often referred to God using terms such as Providence, the Almighty, or the Divine Author, emphasizing divine intervention in both personal and national affairs. While he avoided overt displays of religious fervor or evangelism, he found solace and guidance in daily prayer and the reading of scripture.

Washington’s religious views were marked by a commitment to religious tolerance and inclusivity, reflecting the diverse religious landscape of the newly formed United States. He attended services of various Christian denominations and upheld the principles of religious freedom, denouncing bigotry and superstition. Freemasonry also played a significant role in Washington’s spiritual life, as he was drawn to its moral teachings and principles of brotherhood.

Initiated into the Masonic Order at a young age, Washington held the institution in high regard, although his attendance at lodge meetings was irregular due to his military and political duties. Despite this, he maintained connections with Masonic lodges and members throughout his life, recognizing the value of their teachings and camaraderie.

In essence, George Washington’s religious and spiritual views reflected a blend of Enlightenment rationalism, Christian values, and a commitment to moral integrity and inclusivity, shaping his legacy as not only a founding father but also a man of deep faith and principle.

Washington’s slaves

George Washington’s relationship with slavery is a complex and evolving aspect of his life, reflecting the contradictions and moral dilemmas of his time. As a Virginia planter, Washington owned and rented enslaved African Americans, with over 577 slaves living and working at Mount Vernon during his lifetime.

Initially, Washington’s views on slavery aligned with those of many Virginia planters, but over time, he began to question and ultimately oppose the institution. Economic considerations, such as the surplus of slaves resulting from his transition to grain crops, combined with the principles of the Revolution, contributed to his growing disillusionment with slavery. However, despite his personal reservations, Washington remained dependent on slave labor to operate his farms.

Accounts of slave treatment at Mount Vernon vary, with some suggesting frugality in providing for slaves’ basic needs, while others depict a more generous provision of food, clothing, and housing. Washington’s management of his slaves involved a combination of discipline, reward, and punishment, with measures ranging from appeals to pride to the use of corporal punishment as a last resort.

Washington’s presidency also involved complexities related to slavery, including the strategic rotation of his slave household staff between the federal capital and Mount Vernon to circumvent state abolition laws. Instances of slave escapes, such as those of Ona Judge and Hercules Posey, further underscore the challenges and ethical dilemmas Washington faced as a slave owner.

By the end of his life, Washington’s slave population at Mount Vernon had grown significantly, despite his efforts to support those who were too young or old to work. His legacy regarding slavery is one of ambiguity, reflecting the tensions between his personal beliefs, economic interests, and the social and political realities of his time.

Abolition and manumission

George Washington’s journey toward abolitionism was a complex evolution, influenced by various factors throughout his life. Initially, like many other Virginia planters of his time, Washington owned and relied on enslaved African Americans to work his estate at Mount Vernon. However, as he navigated the turbulent times of the Revolutionary War and the formation of the new nation, his views on slavery began to shift.

During the war, Washington encountered the inherent contradictions between fighting for freedom and owning slaves. He witnessed the contributions of free and enslaved African Americans to the cause of independence, which prompted him to reconsider the institution of slavery. His experiences led him to express his desire to “get quit of Negroes” in a letter to Lund Washington in 1778, indicating a growing discomfort with the practice.

Throughout the 1780s, Washington’s views on slavery continued to evolve. He privately expressed support for gradual emancipation efforts and contemplated various plans to transition away from slave labor. Despite these inclinations, Washington remained cautious about openly advocating for abolition, recognizing the divisive nature of the issue and its potential impact on the fragile unity of the new nation.

By the time of his presidency, Washington’s moral reservations about slavery were evident in his private conversations and correspondence. Although he refrained from taking bold public stances on the matter, his actions behind the scenes reflected a growing sympathy toward abolitionism.

In his final will, Washington made a definitive statement against slavery by stipulating the emancipation of all his slaves upon Martha’s death. This decision was not only a personal acknowledgment of the injustice of slavery but also a practical acknowledgment of the changing economic landscape and moral climate of the time.

Martha Washington honored her husband’s wishes by signing an order to free his slaves on January 1, 1801, one year after George Washington’s death. This act marked a significant step toward the eventual abolition of slavery on his estate and reflected Washington’s commitment to justice and human dignity, despite the complexities and challenges involved.

Historical reputation and legacy

George Washington’s legacy looms large over American history, with his contributions as a military leader, revolutionary figure, and the first president of the United States leaving an indelible mark. Widely regarded as a founding father and a central figure in America’s establishment, Washington earned accolades such as “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen,” a testament to his enduring impact.

Throughout his life, Washington set numerous precedents for the nation’s government and presidency, earning him the title “Father of His Country.” His leadership during the Revolutionary War and his role in guiding the fledgling nation through its early years cemented his reputation as a symbol of liberation and nationalism, both at home and abroad.

Despite his Federalist affiliations, Washington’s influence transcended party lines, earning him recognition from various quarters. Congress declared his birthday a federal holiday in 1879, and he was posthumously honored with the title of General of the Armies of the United States, a testament to his unmatched stature in American military history.

However, Washington’s legacy is not without scrutiny. Historians have examined his attitudes and actions toward Native Americans, noting his efforts to encourage them to adopt agricultural lifestyles while also acknowledging the devastating impact of his policies on indigenous communities. Similarly, Washington’s ownership of enslaved people remains a controversial aspect of his legacy, prompting debates over his moral character and calls for the removal of his name from public spaces.

Despite these criticisms, Washington’s character and leadership continue to be subjects of admiration and study. Whether viewed as a flawed figure grappling with complex issues of his time or as a towering symbol of American ideals, his impact on the nation’s history is undeniable, making him one of the most revered and scrutinized figures in American history.